The changing world economy since 1900- 2 | UPSC Mains: World History PDF Download

The Split in The Third World Economy

During the 1970s some Third World states began to become more prosperous, sometimes thanks to the exploitation of natural resources such as oil, and also because of industrialization.

(a) Oil

Some Third World states were lucky enough to have oil resources. In 1973 the members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), partly in an attempt to conserve oil supplies, began to charge more for their oil. The Middle East oil-producing states made huge profits, as did Nigeria and Libya. This did not necessarily mean that their governments spent the money wisely or for the benefit of their populations. One African success story, however, was provided by Libya, the richest country in Africa thanks to its oil resources and the shrewd policies of its leader, Colonel Gaddafi (who took power in 1969). He used much of the profits from oil on agricultural and industrial development, and to set up a welfare state. This was one country where ordinary people benefited from oil profits; with a GNP of £5460 in 1989, Libya could claim to be almost as economically successful as Greece and Portugal, the poorest members of the European Community.

(b) Industrialization

Some Third World states industrialized rapidly and with great success. These included Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Hong Kong (known as the four ‘Pacific tiger’ economies), and among others, Thailand, Malaysia, Brazil and Mexico.

The GNPs of the four ‘tiger’ economies compared favourably with those of many European Community countries. The success of the newly industrialized countries in world export markets was made possible partly because they were able to attract firms from the North who were keen to take advantage of the much cheaper labour available in the Third World. Some firms even shifted all their production to newly industrialized countries, where low production costs enabled them to sell their goods at lower prices than goods produced in the North. This posed serious problems for the industrialized nations of the North, which were all suffering high unemployment during the 1990s. It seemed that the golden days of western prosperity might have gone, at least for the foreseeable future, unless their workers were prepared to accept lower wages, or unless companies were prepared to make do with lower profits.

In the mid-1990s the world economy was moving into the next stage, in which the Asian ‘tigers’ found themselves losing jobs to workers in countries such as Malaysia and the Philippines. Other Third World states in the process of industrializing were Indonesia and China, where wages were even lower and hours of work longer. Jacques Chirac, the French president, expressed the fears and concerns of many when he pointed out (April 1996) that developing countries should not compete with Europe by allowing miserable wages and working conditions; he called for a recognition that there are certain basic human rights which need to be encouraged and enforced:

- freedom to join trade unions and the freedom for these unions to bargain collectively, for the protection of workers against exploitation;

- abolition of forced labour and child labour.

In fact most developing countries accepted this when they joined the International Labour Organization (ILO) (see Section 9.5(b)), but accepting conditions and keeping to them were two different things.

The World Economy And Its Effects On The Environment

As the twentieth century wore on, and the North became more and more obsessed with industrialization, new methods and techniques were invented to help increase production and efficiency. The main motive was the creation of wealth and profit, and very little attention was paid to the side effects all this was having. During the 1970s people became increasingly aware that all was not well with their environment, and that industrialization was causing several major problems:

- Exhaustion of the world’s resources of raw materials and fuel (oil, coal and gas).

- Massive pollution of the environment. Scientists realized that if this continued, it was likely to severely damage the ecosystem. This is the system by which living creatures, trees and plants function within the environment and in which they are all interconnected. ‘Ecology’ is the study of the ecosystem.

- Global warming – the uncontrollable warming of the Earth’s atmosphere caused by the large quantities of gases emitted from industry.

(a) Exhaustion of the world’s resources

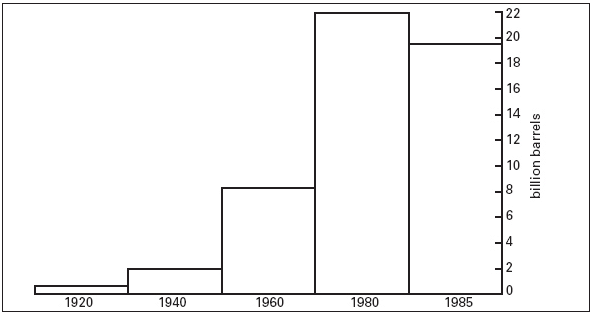

- Fossil fuels – coal, oil and natural gas – are the remains of plants and living creatures which died hundreds of millions of years ago. They cannot be replaced, and are rapidly being used up. There is probably plenty of coal left, but nobody is quite sure just how much remains of the natural gas and oil. Oil production increased enormously during the twentieth century, as Figure 27.2 shows. Some experts believe that all the oil reserves will be used up early in the twenty-first century. This was one of the reasons why OPEC tried to conserve oil during the 1970s. The British responded by successfully drilling for oil in the North Sea, which made them less dependent on oil imports. Another response was to develop alternative sources of power, especially nuclear power.

- Tin, lead, copper, zinc and mercury were other raw materials being seriously depleted. Experts suggested that these might all be used up early in the twenty-first century, and again it was the Third World which was being stripped of the resources it needed to help it escape from poverty.

- Too much timber was being used. About half of the world’s tropical rainforests had been lost by 1987, and it was calculated that about 80 000 square kilometres, an area roughly the size of Austria, was being lost every year. A side effect of this was the loss of many animal and insect species which had lived in the forests.

- Too many fish were being caught and too many whales killed.

- The supply of phosphates (used for fertilizers) was being rapidly used up. The more fertilizers farmers used to increase agricultural yields in an attempt to keep pace with the rising population, the more phosphate rock was quarried (an increase of 4 per cent a year since 1950). Supplies were expected to be exhausted by the middle of the twenty-first century.

- There was a danger that supplies of fresh water might soon run out. Most of the fresh water on the planet is tied up in the polar ice caps and glaciers, or deep in the ground. All living organisms – humans, animals, trees and plants – rely on rain to survive. With the world’s population growing by 90 million a year, scientists at Stanford University (California) found that in 1995, humans and their farm animals, crops and forestry plantations were already using up a quarter of all the water taken up by plants. This leaves less moisture to evaporate and therefore a likelihood of less rainfall.

- The amount of land available for agriculture was dwindling. This was partly because of spreading industrialization and the growth of cities, but also because of wasteful use of farmland. Badly designed irrigation schemes increased salt levels in the soil. Sometimes irrigation took too much water from lakes and rivers, and whole areas were turned into deserts. Soil erosion was another problem: scientists calculated that every year about 75 billion tons of soil were washed away by rain and floods or blown away by winds. Soil loss depended on how good farming practices were: in western Europe and the USA (where methods were good), farmers lost on average 17 tons of topsoil every year from each hectare. In Africa, Asia and South America, the loss was 40 tons a year. On steep slopes in countries like Nigeria, 220 tons a year were being lost, while in some parts of Jamaica the figure reached 400 tons a year.

Figure: World oil production in billions of barrels per year

An encouraging sign was the setting-up of the World Conservation Strategy (1980), which aimed to alert the world to all these problems.

(b) Pollution of the environment – an ecological disaster?

- Discharges from heavy industry polluted the atmosphere, rivers, lakes and the sea. In 1975 all five Great Lakes of North America were described as ‘dead’, meaning that they were so heavily polluted that no fish could live in them. About 10 per cent of the lakes in Sweden were in the same condition. Acid rain (rain polluted with sulphuric acid) caused extensive damage to trees in central Europe, especially in Germany and Czechoslovakia. The USSR and the communist states of eastern Europe were guilty of carrying out the dirtiest industrialization: the whole region was badly polluted by years of poisonous emissions.

- Getting rid of sewage from the world’s great cities was a problem. Some countries simply dumped sewage untreated or only partially treated straight into the sea. The sea around New York was badly polluted, and the Mediterranean was heavily polluted, mainly by human sewage.

- Farmers in the richer countries contributed to the pollution by using artificial fertilizers and pesticides, which drained off the land into streams and rivers.

- Chemicals known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), used in aerosol sprays, refrigerators and fire extinguishers, were found to be harmful to the ozone layer which protects the Earth from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. In 1979, scientists discovered that there was a large hole in the ozone layer over the Antarctic; by 1989 the hole was much larger and another hole had been discovered over the Arctic. This meant that people were more likely to develop skin cancers because of the unfiltered radiation from the sun. Some progress was made towards dealing with this problem, and many countries banned the use of CFCs. In 2001 the World Meteorological Organization reported that the ozone layer seemed to be mending.

- Nuclear power causes pollution when radioactivity leaks into the environment. It is now known that this can cause cancer, particularly leukaemia. It was shown that of all the people who worked at the Sellafield nuclear plant in Cumbria (UK) between 1947 and 1975, a quarter of those who have since died, died of cancer. There was a constant risk of major accidents like the explosion at Three Mile Island in the USA in 1979, which contaminated a vast area around the power station. When leaks and accidents occurred, the authorities always assured the public that nobody had suffered harmful effects; however, nobody really knew how many people would die later from cancer caused by radiation.

The worst ever nuclear accident happened in 1986 at Chernobyl in Ukraine (then part of the USSR). A nuclear reactor exploded, killing 35 people and releasing a huge radioactive cloud which drifted across most of Europe. Ten years later it was reported that hundreds of cases of thyroid cancer were appearing in areas near Chernobyl. Even in Britain, a thousand miles away, hundreds of square miles of sheep pasture in Wales, Cumbria and Scotland were still contaminated and subject to restrictions. This also affected 300 000 sheep, which had to be checked for excessive radioactivity before they could be eaten. Concern about the safety of nuclear power led many countries to look towards alternative sources of power which were safer, particularly solar, wind and tide power.

One of the main difficulties to be faced is that it would cost vast sums of money to put all these problems right. Industrialists argue that to ‘clean up’ their factories and eliminate pollution would make their products more expensive. Governments and local authorities would have to spend extra cash to build better sewage works and to clean up rivers and beaches. In 1996 there were still 27 power-station reactors in operation in eastern Europe of similar elderly design to the one which exploded at Chernobyl. These were all threatening further nuclear disasters, but governments claimed they could afford neither safety improvements nor closure. The following description of Chernobyl from the Guardian (13 April 1996) gives some idea of the seriousness of the problems involved:

At Chernobyl, the scene of the April 1986 explosion, just a few miles north of the Ukrainian capital Kiev, the prospect is bleak. Two of the station’s remaining reactors are still in operation, surrounded by miles of heavily contaminated countryside. Radioactive elements slowly leach into the ground water – and hence into Kiev’s drinking supply – from more than 800 pits where the most dangerous debris was buried ten years ago.

Nuclear reactors were also at risk from natural disasters. In May 2011 a huge tsunami hit the north-east coast of Japan. As well as killing thousands of people, it flooded a nuclear power station in Fukushima. First the six nuclear reactors were battered by high waves, and then the basement, where the emergency generators were situated, was submerged, disabling the entire plant. Again the ongoing problem was how best to deal with the widespread radioactive contamination. There was a great outburst of anti-government feeling when it later emerged that the authorities had ignored and then lied about reports of design weaknesses in the reactors.

(c) Genetically modified (GM) crops

- One of the economic issues that came to the forefront during the 1990s, and which developed into a political confrontation between the USA and the EU, was the growing of genetically modified crops. These are plants injected with genes from other plants which give the crops extra characteristics. For example, some crops can be made to tolerate herbicides that kill all other plants; this means that the farmer can spray the crop with a ‘broad-spectrum’ herbicide that will destroy every other plant in the field except his crop. Since weeds use up precious water and soil nutrients, GM crops should produce higher yields and require less herbicide than conventional crops. Some GM crops have been modified to produce a poison which kills pests that feed on them, others have been modified so that they will grow in salty soil. The main GM crops grown are wheat, barley, maize, oilseed rape, soya beans and cotton. Advocates of GM crops claim that they represent one of the greatest advances ever achieved in farming; they provide healthier food, produced in a more efficient and environmentally friendly way. Given the problem of the growing world population and the difficulties of feeding everybody, supporters see GM crops as perhaps a vital breakthrough in solving the world food problem. By 2004 they were being grown by at least 6 million farmers in 16 countries, including the USA, Canada, India, Argentina, Mexico, China, Colombia and South Africa. The main supporters of GM crops were the Americans, who were also the world’s largest exporter.

- However, not everybody was happy about this situation. Many people object to GM technology on the grounds that it can be used to create unnatural organisms – plants can be modified with genes from another plant or even from an animal. There are fears that genes might escape into wild plants and create ‘superweeds’ that cannot be killed; GM crops might be harmful to other species and also in the long term to the humans who eat them. Genes escaping from GM crops might be able to pollinate organically growing crops, which would ruin the organic farmers involved. These unfortunate farmers might find themselves being sued for having GM genes in their crops, even though they had not knowingly planted such seeds. The main objections came from Europe; although some European countries – Germany and Spain for example – grew GM crops, the amounts were small. Scientists on the whole tended to reserve judgement, claiming that there should be long field trials to show whether or not GM crops were harmful, both for the environment and for public health. Opinion polls showed that around 80 per cent of the European public had grave doubts about their safety; several countries, including Austria, France, Germany, Italy and Greece, banned imports of individual GMs either for growing or for use as food. Americans, on the other hand, insisted that the crops had been thoroughly tested and approved by the government, and that people had been eating GM foods for several years without any apparent ill effects.

- Another European objection was that the GM industry was controlled by a few giant agriculture businesses, most of them American. In fact, by 2004 the American company Monsanto was producing more than 90 per cent of GM crops worldwide. The feeling was that such companies had too much control over world food production, which would enable them to exert pressure on countries to buy their products and force more traditional farmers out of the market. The controversy came to a head in April 2004 when the USA called on the World Trade Organization (WTO) to take action. The USA accused the EU of breaking WTO free-trade rules by banning GM imports without any scientific evidence to support their case.

- However, by no means does everybody in the USA support GM farming. An organization called the Centre for Food Safety (CFS) has launched several cases in the Supreme Court, most notably in 2006 when a group of organic alfalfa farmers sued Monsanto for growing GM alfalfa, without first carrying out safety checks. They were afraid that their organic alfalfa would be cross-pollinated by GM alfalfa, which would make their organic alfalfa unsaleable in countries where GM crops were banned. The judgement was that the planting of GM alfalfa should stop until a full-scale investigation into possible ill effects had been carried out. A spokesman for Monsanto stated that they were confident that tests would be completed in time for the autumn planting in 2010. Encouraged by this result, the CFS organized another lawsuit against Monsanto in 2009, this time against the growing of GM sugar beet. In August 2010 a similar judgement halted the planting of GM sugar beet until the necessary tests had been completed.

- At the same time not everybody in Europe was against GM farming. In Britain, for example, at the Rothamsted Agricultural Research Centre at Harpenden, experiments were being carried out with GM wheat which is resistant to several kinds of insects and should therefore need fewer pesticides. In June 2012 a group of protesters calling themselves ‘Take the Flour Back’ threatened to destroy the crop. Several hundred protesters, including some from France, attempted to invade the research centre, but were prevented by a large police presence. Fortunately they were persuaded to call off their plan and meet the research team for discussions. At the end of June 2012 it was revealed that recent tests in China on GM cotton crops showed that some insects were developing increased resistance to these crops, and that an increasing number of other pests were developing in and around the cotton crop, and these were affecting surrounding crops too. In other words, the early benefits were now being replaced by unexpected problems. And so the basic problem still remains: how is agriculture going to produce enough to feed the steadily growing world population, given that the amount of land suitable for agricultural production makes up only about 11 per cent of the earth’s surface, and that a lot of this land is being contaminated by salt (salination), and therefore unsuitable for agriculture? Continuing global warming and rising sea levels are not likely to improve the situation (see the next section). At least there was one piece of good news in 2012 – in March it was announced that Australian scientists had tested a new strain of wheat that could increase yields by 25 per cent in saline soils. Perhaps in the end, if the world is to survive, we shall have no choice but to accept GM produce. On the other hand it could be that scientists will succeed in producing new non-GM strains of all foodstuffs, like the Australian wheat, which will give higher yields from the same size of land area.

Capitalism In Crisis

(a) Meltdown – the Great Crash of 2008

- On 15 June 2007 Ben S. Bernanke, chairman of the American Federal Reserve Bank, made a long speech in which he extolled the virtues of the American financial system:

- In the United States, a deep and liquid financial system has promoted growth by effectively allocating capital, and has increased economic resilience by increasing our ability to share and diversify risks both domestically and globally.

- There was, he said, no possibility of a financial crisis in America. Yet, little over a year later the American system and the whole global economy seemed to be on the verge of total collapse. In fact some experts had been predicting collapse for some years, but had been proved wrong. However, in March 2008 the unthinkable happened – it was revealed that one of the oldest and most respected Wall Street investment banks, Bear Stearns, was in serious trouble. It had lost $1.6 billion when some affiliated hedge funds collapsed, but much worse, it had a problem with bad debts estimated at $220 billion. Reluctantly, US treasury secretary, Henry Paulson, decided that Bear Stearns could not be allowed to collapse, since that might inconvenience or even ruin many of the rich citizens who had entrusted their wealth to the bank. There was a rule that the US government should never bail out an investment bank, so it was arranged that another bank, J. P. Morgan, should be provided with Federal Reserve funds to enable it to take over Bear Stearns. This indirect Federal Reserve bailout of Bear Stearns saved the system from collapsing. Unfortunately, it also left the impression that any other bank that got itself into difficulties would always be able to rely on a government bailout. In financial circles this was described as ‘moral hazard’ – the idea that there are some investors who believe that they are ‘too big to fail’, and who therefore take reckless risks.

- The fourth largest bank on Wall Street, Lehman Brothers, had been struggling for over a year with problems of bad debts and a shortage of capital. In August 2008 it too was on the verge of bankruptcy and no other bank was willing to bail it out. In September its European branch based in London was put into administration, but there was wide expectation in the USA that the government would come to the rescue with a Bear Stearns-type deal. But this time there was to be no bailout – Tim Geithner of the Federal Reserve of New York state announced that there was ‘no political will’ for a Federal rescue. Lehman Brothers was allowed to go bankrupt; it was the largest US company until then ever to go bust. The collapse sent shock waves around the world, and share prices plummeted. Why was Lehman Brothers allowed to collapse? Government and state financial bosses like Paulson and Geithner were determined that there should be no such thing as ‘moral hazard’ – state takeovers should not become a habit, because it was seen as state capitalism. In a country that almost worshipped free-market capitalism, the idea that private companies and banks should be subsidized or taken over by the government was sacrilege. One leading financier remarked: ‘I just think it is disgusting; this is not American.’

- Unfortunately, the crisis worsened rapidly and the government found it impossible to maintain its free-market stance. Another struggling investment bank, Merrill Lynch, was taken over by the Bank of America (BOA). Then came the biggest sensation so far: a giant insurance company, American International Group (AIG), asked the government for a loan of $40 billion to stave off bankruptcy. Like the failing investment banks, AIG had too many bad or ‘toxic’ debts, as they were now being called. The government was in a dilemma: AIG was so big and had done so much business with most of the major financial institutions worldwide, that if it were allowed to collapse the repercussions would be catastrophic. Consequently it was decided that AIG should be bailed out with a government loan of $85 billion, although the state took an 80 per cent stake in the company. In effect, the US government had nationalized AIG, though the word itself was never used.

- The UK banking system was already in trouble before the US crisis began, mainly because the Bank of England was reluctant to pump money into the system and failed to reduce interest rates on borrowing. The UK mortgage bank, Northern Rock, which had been forced to reduce its lending because of its own dependence on short-term borrowing (see below (b)3), collapsed in September 2007. It was eventually nationalized at a cost of some £100 billion. In September 2008 Halifax Bank of Scotland (HBOS) was saved from collapse when it was taken over by Lloyds TSB for £12 billion in a deal arranged by British prime minister Gordon Brown. However, its share price fell rapidly, so that only a few weeks later its value had slumped to £4 billion. This brought Lloyds TSB to its knees as well and it too had to be rescued by the government. Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) was partly nationalized, so that it became 83 per cent taxpayer-owned. Shares in European banks followed suit; Fortis, the huge Dutch–Belgian bank, lost almost half its value in just a few days and was taken into joint ownership by the two governments. In Germany, France, the Irish Republic and Iceland similar bailouts were taking place. And most of this happened in just a few days in September 2008. The situation was exacerbated by millions of ordinary depositors rushing to withdraw their funds from the banks. Lending between banks had more or less dried up because the inter-bank lending rates (known as LIBOR) were prohibitive.

- By the time the crisis passed, the US Treasury had acquired stakes in several more major financial institutions, including Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, J. P. Morgan Chase, and two mortgage underwriters, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. The function of these last two institutions was not to provide mortgages directly to house-buyers, but to act as an insurance by underwriting mortgages given by other banks. Much of the help was provided under the Bush administration’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and later by the Obama administration’s Public–Private Investment Program. According to an official report in July 2009, TARP had saddled the taxpayers of the USA with a debt of $27.3 trillion. By that time the crisis had developed into a global recession. The whole bailout operation was extremely controversial. President Bush was accused of being un-American and of introducing socialism. To get the TARP approved by Congress it was necessary to attach several conditions: limits on executive pay, a cap on dividends and the right of the government to take stakes in the ailing banks.

(b) What were the causes of the great crash?

- Paul Mason, economics editor of the BBC Newsnight programme, sums up the causes of the crisis neatly in his book Meltdown (2010):

- If you exalt the money-changers, exhort them to make more money and hail the ascendancy of speculative finance as a ‘golden age’, this is what you get. The responsibility for what happened must lie, as well as with any banker found to have broken the law, with regulators, politicians and the media who failed to hold them up to scrutiny.

- He argues that the system known as neo-liberalism that had been in operation for the last quarter of a century was mainly responsible for the catastrophe. In the words of Sir Keith Joseph, a UK Conservative supporter of the free-market system, neo-liberalism involved ‘the strict and unflinching control of money supply, substantial cuts in tax and public spending and bold incentives and encouragements to the wealth creators’.

- Beginning in the last decade of the twentieth century, globalization played an important role, as national economies became interlinked as never before. In the 20 years after 1990 the world’s labour force doubled and with the increase in migration, became global. China and the former Soviet bloc joined the world economy. The greater availability of labour brought a fall in real wages in the leading western economies, including the USA, Japan and Germany. Yet consumption grew, made possible by a massive increase in credit and the heyday of the credit-card era. The credit boom seemed sustainable at first but after 2000 the debts began to run out of control. At the same time capital flowed around as western financiers began to invest abroad more than ever before, and this caused a huge rise in global imbalances. For example, China’s foreign currency reserves grew from $150 billion in 1999 to $2.85 trillion in 2010; but between 1989 and 2007 the US deficit increased from $99 billion to $800 billion. So long as the US housing boom continued, the situation was just about sustainable, but once house prices began to falter, chaos was unleashed as the amount of toxic debts soared. To look at the steps towards meltdown in more detail:

1. The deregulation of the US banking industry in 1999–2000

- In November 1999 the US Congress passed an act designed to promote economic growth through competition and freedom. This cancelled the regulation, dating from the Depression of the 1930s, that prevented investment banks from handling the savings and deposits of the general public, and meant that they now had access to far larger funds. Banks were also allowed to act as insurance companies. A year later futures and all other derivatives were exempted from being classified as gambling and all attempts to regulate the derivatives market were declared illegal. Probably the most common type of derivatives are futures; a future is a contract in which you agree to buy something at a future date, but at a price decided on now. The hope is that in the meantime the price will go up, enabling you to sell it again at a profit. The actual contract between the two parties can itself be sold and resold several times before the agreed date. However, there is a risk involved: in the meantime the price might fall, but you still have to pay the agreed price. Another type of derivative develops when observers start betting among themselves on whether the original contract will be fulfilled. The option derivative is similar to a future except that you simply agree the option to buy, rather than actually buying the commodity itself.

- The deregulation, together with the spread of the latest computer technology, was certainly a ‘bold incentive and encouragement’ to the bankers who now had a free hand to indulge in all these types of speculation. It enabled the derivatives market to become global, and foreign-exchange dealing increased rapidly. In the two years leading up to the crash, there was a massive rush of money into derivatives and currency trading. The statistics are staggering: in 2007 the total value of the world’s stock market companies was $63 trillion; but the total value of derivative investments stood at $596 trillion – eight times the size of the real economy. It was as though there were two parallel economies – the real economy and a kind of phantom or fantasy economy which only existed on paper. Admittedly, not all the derivative dealings were speculative, but enough of them were risky to cause concern among perceptive financiers. As early as 2002 Warren Buffett, probably the world’s most successful investor, warned that derivatives were a time bomb, financial weapons of mass destruction, because in the last resort, neither banks nor governments knew how to control them. Paul Mason concludes that since the end of the 1990s, ‘this new global finance system has injected gross instability into the world economy’. By October 2008, even Alan Greenspan, a former chairman of the Federal Reserve, who had always claimed that banks could be trusted to regulate themselves, was forced to admit that he had been wrong. By the time the crisis peaked, some 360 banks had received capital from the US government.

2. Sub-prime mortgages and the collapse of the US housing market

- The long-running housing boom in the USA reached a peak towards the end of 2005. House prices had been rising steadily and had reached levels that could not be sustained. Too many houses had been built, demand gradually fell and so did prices. The unfortunate thing was that many houses, especially during the latter stages of the boom, had been bought using sub-prime mortgages. These are mortgages lent to borrowers who have a high risk of being unable to keep up the payments, and for that reason sub-prime borrowers have to pay a higher interest rate. As house prices were rising, mortgage providers were able to repossess houses whose buyers defaulted on their mortgage payments, and make a profit from selling them on. When house prices began to fall, many lenders foolishly continued to push sub-prime mortgages, and suffered heavy losses when the buyers defaulted. The more careful mortgage providers took out insurance to underwrite their loans, so insurance companies like AIG, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae were faced with huge payouts. Niall Ferguson, in one of his 2012 Reith Lectures, suggested that Freddie and Fannie should take a large slice of the blame for the crisis, because they encouraged people who really couldn’t afford to do so to take out mortgages.

- Another of the practices that contributed to the meltdown was known as collateral debt obligation (CDOs). This was the packaging together of different debts and bonds for sale as assets; a package might include sub-prime mortgages, credit-card debts and any kind of debt, and anybody buying the package would hope to receive reasonable interest payments. In fact since the year 2000, buyers, which included investment banks, pension funds and building societies, had been receiving interest payments on average between 2 and 3 per cent higher than if the debts had not been bundled up. But then several things went wrong – houses prices fell by around 25 per cent, more people defaulted on the mortgage payments than had been expected, unemployment rose, and many people were unable to pay off their credit-card debts. One estimate put the likely losses to buyers at $3.1 trillion.

3. Leverage, short selling and short-termism

- These were other tactics in which banks indulged in order to make money, and which eventually ended in disaster. Leverage is using borrowed money to increase your assets which can then be sold at a profit when the value increases. Lehman was guilty of this, having a very high leverage level of 44. This means that every $1 million owned by the bank had been stretched by borrowing so that they were able to buy assets valued at $44 million. In a time of inflation like the period 2003–6, these assets could be sold at a comfortable profit. But it was gamble, because only a small downward movement in the value of the assets would be enough to break the bank. As John Lanchester explains:

- Lehman made gigantic investments in the property market, not just in the now notorious sub-prime mortgages, but also to a huge extent in commercial property. In effect, Fuld [Richard Fuld, head of Lehman Brothers] allowed his colleagues to bet the bank on the US property market. We all know what happened next.

- As US house prices collapsed and the number of mortgage defaulters soared, Lehman was left with debts of $613 billion. In the words of Warren Buffett: ‘when the tide goes out it reveals those who are swimming naked’.

- Short selling is a strange process in which the investor first borrows, for a fee, shares from a bank or other institution which is not planning to sell the shares itself. The investor then sells the shares in the hope that their price will fall. If and when this happens, he buys the shares back, returns them to the owner and keeps the difference. It is the company whose shares are being sold and bought that suffers, as illustrated by the plight of Morgan Stanley. As the crisis deepened investors began to move their money out. In three days 10 per cent of the cash on Morgan Stanley’s books was withdrawn. The share price began to fall and this was the signal for short sellers to unload their Morgan Stanley shares, sending the share price plunging further.

- Short-termism is the common banking practice of lending money for long terms and borrowing it for short terms – you issue a long-term loan and fund it by short-term borrowing yourself. When lending between banks dried up in September 2008 following the rush of depositors to withdraw cash, many banks were unable to pay out. This was because they had lent too much out on long-term loans which they could not get back immediately, and had failed to keep to the rule that they must hold a large enough ‘cushion’ to fall back on. Many banks tried to get round this regulation by setting up a sort of ‘shadow’ banking system. Paul Mason explains how the system worked:

- The essence of the shadow banking system is that it is designed to get round the need for any capital cushion at all. Almost everybody in the shadow system was ‘borrowing short’ by buying a piece of paper on the vast international money market, and then ‘lending long’ by selling a different piece of paper into that same money market. So it was basically just traditional banking: but they were doing it with no depositors, no shareholders and no capital cushion to fall back on. They were pure intermediaries. They did it by exploiting a loophole in the regulations to create two kinds of off-balance sheet companies known as ‘conduits’ and ‘structured investment vehicles’ (SIVs). … The conduits were set up by banks in offshore tax havens. The bank would, theoretically, be liable for any losses, but it did not have to show this on its annual accounts.

- Incredible as it may seem, all this was kept secret from investors, which didn’t matter when all was running smoothly. But there was one huge flaw in the system: it could only work as long as bankers continued to buy and sell everything on offer. As soon as short-term credit was no longer available, bankers could not fund their long term loans, and inevitably some pieces of paper became unsaleable.

4. Regulators and credit-rating agencies failed to do their job satisfactorily

Since 2000, thanks to the actions of both the US and UK governments, regulation of the banking system had been exercised with what can only be described as a light touch. The politicians were apparently happy to continue this non-interventionist attitude since bankers had played an important part in achieving the consumer boom and full employment. They mistakenly believed that bankers could therefore be trusted not to do anything too risky. The credit-rating agencies were the second line of defence against high risk. The three main agencies are Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch. Their job is to carry out a risk-assessment process on banks, companies and assets and award grades showing investors whether or not it would be safe to do business with them. The safest gets an AAA rating, while BB or less indicates a high-risk institution or commodity. Between 2001 and 2007 the amount of money paid to the three main credit rating agencies doubled, reaching a total of $6 billion. Yet an official report published in July 2007 was highly critical of the work of the rating agencies. They were accused of being unable to show convincing evidence that their methods of assessment were reliable, especially in the case of CDOs. They were unable to cope with the vast increase in the amount of new business that they were called on to do since 2000. Many critics saw the whole system as suspect: the fact that institutions and sellers of bonds actually paid for their own ratings invited ‘collusion’; if they gave the correct ratings, they risked upsetting the banking business and losing market share. As a result, no decisive action was taken until it was too late. For example, it was only a matter of hours before the British HBOS collapsed in September 2008 that Standard and Poor’s downgraded it, and even then the comforting phrase, ‘but the outlook is stable’, was added.

(c) The aftermath of the crash

Although the capitalist financial system had been saved from total collapse, the consequences of the crisis were clearly going to be felt for a long time. As the money supply dried up, demand for goods fell, and across the world, manufacturing industry slumped. Many of the weakest companies went to the wall and unemployment rocketed. In the USA in the first few months of 2009 it was calculated that around half a million jobs a month were being lost. The great exporting nations like China, Japan, South Korea and Germany suffered huge falls in exports. Although central bank interest rates were almost zero in the USA and Britain, nobody was investing to try to stimulate the still declining economy. Attempts to deal with this problem included:

- Fiscal stimulus provided by governments and central banks. As early as November 2009 the Chinese government had decided to supply cash worth $580 billion over the next two years to fund various environmental projects. Banks were encouraged to lend vast sums of money, guaranteed by the state, to fund other projects. Millions of new jobs were created, and within a few months China’s economic growth rate had recovered and surpassed its previous high point. The main problem was the uncertainty about how risky those massive bank loans were.

In the USA, newly elected Democrat president Barack Obama’s fiscal stimulus of $787 billion went into operation in February 2009. It was a controversial move because the Republican party was totally against it; even in a crisis as serious as this, they believed that the state should not be expected to provide help. A right-wing Republican group calling themselves the Tea Party Movement launched an anti-stimulus protest campaign encouraging Republican state governors not to accept stimulus money. Although the US economy did begin to grow again towards the end of 2009 and continued slowly through 2010, there were still 15 million unemployed at the end of the year.

In the EU the effects of the crisis varied among its 27 member states. They experienced different degrees of recession, though the average growth reduction at the end of 2009 was 4.7 per cent. The three Baltic states fared the worst, suffering full-scale slump: Estonia’s GDP fell by 14 per cent, Lithuania’s by 15 per cent and Latvia’s by 18 per cent. France did best, losing only 3 per cent of GDP. Most states borrowed heavily in order to launch fiscal-stimulus packages. For example, in 2009 France’s borrowing was equivalent to 8 per cent of GDP and Britain’s was 11 per cent. These amounts were quite small compared with America’s and China’s, but in the case of France they were successful: as early as August 2009 the French economy was growing again. The problem was that they were all left with massive national debts. Those countries which had signed up to the Maastricht Agreement of 1991 (see Section 10.4(h)) had broken the rules that borrowing must not exceed 3 per cent of GDP and total debt must be limited to 60 per cent of GDP.

- Quantitative easing (QE). This was the practice, first thought of by John Maynard Keynes back in the 1930s, of increasing the amounts of cash in circulation by ‘printing money’. In fact nowadays banks do not actually print new notes; the central banks simply invent or create more money which is added into their reserves, and then used to buy up government debts. The UK was the first to use QE in March 2009 when a modest £150 billion was ‘created’, and this to some extent helped to put demand back into the system. According to Paul Mason, ‘Britain’s “pure” QE strategy saw it inject around 12 per cent of GDP into the economy. The Bank of England estimates this should, over a period of three to four years, filter through into a 12 per cent increase in the money supply and thus in demand.’ The USA adopted QE soon after Britain. However, the European Central Bank rejected QE on the grounds that it would threaten the stability of the euro. It was argued that simply making more of the existing money available to eurozone banks and buying AAA-rated bonds would be sufficient to stimulate demand. But demand was not sufficiently stimulated and consequently the value of the euro was weakened. By the end of 2009 the eurozone was in big trouble as the cost of all the fiscal stimulus and bank bailouts had to be faced. Some economists were already predicting that the zone was on the verge of break-up. In fact some economists and politicians hoped it would break up, so this seemed an unmissable opportunity!

(d) The eurozone in crisis

- The financial crisis in Greece sparked things off. In October 2009 the newly elected social-democrat government discovered that the country’s budget deficit – which stood at 6 per cent according to the previous government – was in reality 12.7 per cent. Over half its actual debt, with a little assistance from Goldman Sachs, had been moved into the shadow-banking system, ‘off balance sheet’. It later emerged that there were serious flaws in the Greek system that had allowed massive tax evasion and other corrupt practices, such as pensions still being paid to families of the deceased. The immediate problem was that Greece had financed its national debt with short-term loans, a quarter of which were due for repayment in 2010. How were they going to find the necessary €50 billion? The first step was to introduce strict austerity policies – cuts in pensions, wages and social services and a campaign to eliminate tax evasion. Eventually in May 2010 the eurozone banks and the IMF agreed a loan of €110 billion to Greece, provided they fulfilled the austerity programme. This was extremely unpopular with the Greeks, and resulted in strikes and two general elections over the next two years. By the autumn of 2011 there seemed a real danger that Greece would default on its debts. Worried about the disastrous effects this might have on other members of the eurozone, leaders agreed to write off half of Greece’s debts to private creditors.

- Meanwhile some other eurozone countries had also got themselves too heavily in debt. In November 2011 the Republic of Ireland had to be helped with a bailout of €85 billion. Portugal, which had suffered crippling competition from Germany and China, was on the verge of bankruptcy. In July 2011 Moody’s had downgraded Portugal’s debt to ‘junk’ status, and in October it too received an IMF bailout. Portugal had the lowest GDP per capita in western Europe and in March 2012 the unemployment rate was around 15 per cent. By August 2011 Spain and Italy had drifted into the danger zone. Paul Mason explains what happened next (in Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions (2012)):

- The European Central Bank was forced to break its own rules and start buying up the debt of these two massive, unbailable economies. The dilemma throughout the euro crisis has been clear: whether to impose losses from south European bad debts onto north European taxpayers, or onto the bankers who had actually lent the money to these bankrupt countries in the first place. The outcome was always a function of the level of class struggle. By hitting the streets, Greek people were able to force Europe to impose losses on the bankers; where opposition remained within traditional boundaries – the one-day strike, the passive demo – it was the workers, youth and pensioners who took the pain. Meanwhile Europe itself was plunged into institutional crisis. Monetary union without fiscal union had failed.

The World Economies In 2012

- At the turn of the millennium ‘globalization’ had been the buzzword. It seemed to promise huge benefits for the world – increased connectivity between countries, faster growth, greater transfer of knowledge and wealth, and perhaps even a fairer distribution of wealth. Economists talked about the ‘BRIC’ countries, meaning Brazil, Russia, India and China. These were the world’s fastest growing and largest emerging market economies, and between them they contained almost half the world’s population. Many economists were predicting that it was only a matter of time before China became the largest economy in the world, probably some time between 2030 and 2050. Goldman Sachs believed that by 2020 all the BRIC countries would be in the world’s top 10 economies, and that by 2050 they would be the top four, with China in first place. The USA was expected to have been relegated to fifth place.

- There were differing views about actual details of how this scenario would play out. In 2008 the BRIC countries held a summit conference. Many analysts got the impression that they had ulterior motives of turning their growing economic strength into some kind of political power. They could carve out the future economic order between themselves. China would continue to dominate world markets in manufactured goods, India would specialize in providing services, while Russia and Brazil would be the leading suppliers of raw materials. By working together in this way the BRIC states can present an effective challenge to the entrenched interests and systems of the West. However, the fact that these four countries have very little in common could mean that any economic and political cooperation would only be temporary, or rather artificial. Once China becomes the world’s largest economy, it might not need the other three. In that case it could be China and the USA that work together to lead the global economy.

- It was not immediately obvious how the 2008 meltdown would affect the BRIC nations. Many economists believed it would be possible for them to ‘decouple’ themselves from the West and continue growing. This turned out not to be the case and many commentators began to doubt whether globalization had been a ‘good thing’ after all. It seemed as if it had made the world economy less stable, more volatile, and more vulnerable to the danger of a crisis in one country infecting the rest of the world. A brief survey of the world’s leading states shows that, unfortunately, very few were able to avoid the contagion. As a report from Crédit Suisse said: ‘We may not be at the brink of a new global recession, but we are even less likely to be at the threshold of a global boom.’

(a) China

As we saw earlier, the financial crisis of 2008 caused an immediate drop in China’s exports. China launched a great spending spree in 2008 and 2009 to improve the country’s infrastructure and launch a number of environmental projects. This seemed to work at first and China’s growth rate soon recovered. However, this policy was continued through 2010 and 2011 when the total investment was an unprecedented 49 per cent of China’s GDP. There were several problems with this state of affairs. Most observers believed that there was a limit to the number of roads, airports and high-rise flats that China could keep on building, and they feared that there had been an unsustainable building bubble that was about to burst, just as similar bubbles burst earlier in the USA, Spain and Portugal. The concentration on domestic consumption and reduced demand from overseas meant that exports, and therefore revenue from exports, were continuing to decline, and the growth rate was slowing. The Chinese themselves were extremely nervous about their own vulnerability in view of the continuing crisis in the eurozone. So much so that in June 2012, along with India, they contributed tens of billions of dollars to the IMF’s emergency fund for tackling the EU’s ongoing problems.

(b) Brazil

- Like China, Brazil initially responded well to the 2008 economic crisis, launching a massive property-building project. This created thousands of new jobs and unemployment fell to its lowest level for many years. Domestic demand continued at a high level. The economy continued to grow, receiving a huge boost with the discovery of more oil and gas reserves off the coast. By 2012 Brazil had become the world’s ninth largest oil producer, and was hoping eventually to become the fifth largest. It had overtaken Britain and was now rated to be the sixth largest economy in the world. Other good news was that poverty was decreasing – over the last few years, the incomes of the poorest 50 per cent of the population have increased by almost 70 per cent. Brazil will host the 2014 soccer World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics will take place in Rio de Janeiro.

- However, the latest reports suggest that all is not well in Brazil. House prices in Rio have trebled since 2008, causing mortgage borrowing to rocket and raising the prospect of yet another crash if and when the housing bubble should burst. Since some of Brazil’s main exports included raw materials and oil to China, the slow-down in Chinese exports of manufactured goods and the general decline in global demand did not bode well for Brazil’s export trade, especially taking into account the 30 per cent fall in oil prices. Domestic demand fell as consumer confidence waned, and all the analysts were predicting a dramatic slowdown in growth.

(c) India

India’s economy had been expanding rapidly and words like ‘dynamic’ and ‘rampaging Asian tiger’ had been used to describe it. However, as the financial crisis hit the USA and Europe, demand for Indian goods plummeted and was still falling in 2012. In fact, Indian exports fell by a further 3 per cent in the year from May 2011 to May 2012. As the economy slowed down, investors began to desert India, preferring something safer, like the US dollar. This sent the value of the rupee plunging until in June 2012 it reached a record low against the dollar. In theory this should help Indian exports, which would be cheaper; but on the other hand it made India’s imports more expensive, and this pushed up the cost of living, making even essentials difficult to afford. In addition India had further problems: much of its infrastructure was in a dilapidated state, and businesses complained of being hampered by corruption, bribery and unnecessary bureaucracy. The country’s current account deficit stood at $49 billion in June 2011 and was estimated to be $72 billion at the end of 2012, which would be over four per cent of India’s GDP. According to Morgan Stanley, a sustainable deficit ought to be no more than two per cent of GDP. Standard and Poor’s and Fitch both reduced their ratings of the Indian economy to ‘negative’, though Moody’s continued to rate it as ‘stable’. Clearly India had failed to ‘decouple’ itself from the problems of the eurozone. Desperate for the eurozone crisis to be resolved, in June 2012 India joined China in making a substantial contribution to the IMF’s emergency fund.

(d) Russia

- Up until 2008 the Russian economy enjoyed ten years of spectacular growth thanks mainly to high oil prices. GDP increased tenfold, and by 2008 revenues from oil and gas were worth around $200 billion, about one-third of total revenue. The fact that the economy was so dependent on the price of oil meant that there could be no ‘decoupling’ from the rest of the world’s economic problems. The rapid fall in oil prices and in demand for oil had a disastrous effect on Russia: in 2008 the price per barrel plunged from $140 to $40, causing a drastic fall in revenue. The foreign credits that Russian banks and businesses had relied on quickly dried up, leaving many firms unable to pay their debts. The government was forced to help them by providing $200 billion to increase liquidity in the Russian banking sector. The Russian Central Bank also spent a third of its $600 billion international currency reserve fund to slow down the devaluation of the rouble. Fortunately, by the middle of 2009 the slump had bottomed out and the economy began to grow again. In 2011, as well as becoming the world’s leading oil producer, surpassing Saudi Arabia, Russia also became the second largest producer of natural gas and the third largest exporter of steel and aluminium. The high price of oil in 2011 helped the recovery and enabled Russia to reduce the large budget deficit that had accrued during the lean period in 2008 and early 2009.

- However, recognizing the danger of being too dependent on oil, the government successfully encouraged the expansion of other areas. In 2012 Russia was the world’s second largest producer of armaments, including military aircraft, after the USA, and the IT industry had a year of record growth. Companies making nuclear power plants were expanding, and several plants were exported to China and India. In 2012 statistics showed that Russia was the third richest country in the world in terms of cash reserves; inflation had been reduced and unemployment had fallen. Nor was the expansion confined to Moscow and St Petersburg; other cities, including Nizhny Novgorod, Samara and Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad), were playing an important role in the diversification of industry. Of the four BRIC nations Russia was clearly the strongest economically.

(e) The USA

Unemployment, which had stood at 15 per cent at the end of 2010, continued to fall, but only slowly. Fitch ratings agency estimated that President Obama’s fiscal stimulus packages boosted US GDP by 4 per cent over the following two years. However, according to a Guardian report (27 June 2012), ‘the US economy is still limping along with very slow growth and a high rate of unemployment. Although the economy has been expanding for three years, the level of GDP is still only 1 per cent higher than it was nearly five years ago. Recent data shows falling real personal incomes, declining employment gains, and lower retail sales.’ Another problem was that, although mortgage interest rates were low, house prices have continued to fall and in 2012 were 10 per cent lower in real terms than they were two years ago.

At the end of June 2012 the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Paris-based group of independent economists from 34 countries, produced its biannual report on the US economy. This confirmed that the US recovery remained fragile and pointed out that two of the main problems were record long-term unemployment and the widening gap between the poor and the wealthy. About 5.3 million Americans, 40 per cent of unemployed people, have been out of work for six months or more. Poverty in the US is worse than in Europe, and of the 34 OECD member states, only Chile, Mexico and Turkey rank higher in terms of income inequality. The report also suggested measures to remedy the situation:

- Equalize tax rates by ending tax breaks for the very wealthy – in other words, make the rich pay more. Earlier in 2012 the government proposed a measure to make sure that everyone making more than a million dollars a year pays at least 30 per cent in tax. Predictably, this was strongly opposed by the Republicans.

- Provide more investment for education and innovation, and more training programmes to get the long-term unemployed back to work.

- Increase gas prices to help reduce the use of fossil fuels.

- The government should reduce spending, but only gradually, rather than make drastic cuts; these might discourage business investment and slow growth even further.

How the situation would develop depended very much on the results of the presidential and congressional elections held in November 2012. Tax cuts for the wealthy introduced during the Bush administration were due to end on 31 December 2012. Another hangover from the Bush era was that automatic spending cuts would be applied at the end of 2012. The cuts involved, dubbed ‘the fiscal cliff’, would amount to $1.2 trillion.

(f) The European Union

- In the summer of 2012 the future looked uncertain. In June there were tense elections in Greece when the party that was prepared to continue the austerity policy won a narrow victory over the socialist party that resented having austerity forced on the country by outsiders, and was determined to abandon the euro. And so the euro survived again. There was also resentment in some of the more economically successful north European states, especially in Germany, at having to bail out what many saw as the ‘feckless, reckless and lazy’ south. The most likely outcome seemed to be that the taxpayers of northern Europe would bail out the south and would, in effect, take control of overall eurozone economic policy, so that the eurozone would become much closer to being a fiscal union, and therefore, to some extent, a political union as well. Of course the governments of southern Europe resisted losing overall control of their economic policies; but without a bailout of some sort – the eurozone seemed likely to disintegrate.

- On the other hand, many economists and financiers believed that the euro must be saved. In September 2012 Mario Draghi, the president of the European Central Bank (ECB), announced: ‘We say that the euro is irreversible. So, unfounded fears of reversibility are just that – unfounded fears.’ It was felt that the collapse of the euro would throw the entire global economy into chaos. Certainly Germany wanted the euro saved, because the cheap euro benefited German exports, whereas a strong Deutschmark would do considerable damage to their exports. Hopes for the survival of the euro revived in September 2012 when Mario Draghi unveiled a rescue plan that involved the ECB buying up the bonds of Spain and Italy, the two eurozone countries after Greece most heavily in debt. Those governments could then request a bailout from the ECB which would be granted, provided they agreed to implement strict austerity measures. The announcement of the plan received a glowing reception across most of Europe; stock markets soared on both sides of the Atlantic, and so did confidence in the euro’s survival. This was sufficient to bring down borrowing costs for Spain and Italy, and their future seemed brighter. Even the Germans agreed to go along with the scheme. At first the German Bundesbank condemned the whole idea as ‘tantamount to financing governments by printing banknotes’. But eventually, after pressure from Chancellor Merkel and Mario Draghi himself, followed a few days later by the approval of the German constitutional court, the Bundesbank, albeit rather grudgingly, agreed to back the plan. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM), as it was now known, was poised to go into operation with the creation of a rescue fund of €500 billion.

|

50 videos|67 docs|30 tests

|

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|