UPSC Mains Answer PYQ 2020: History Paper 1 (Section- A) | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Section ‘A’

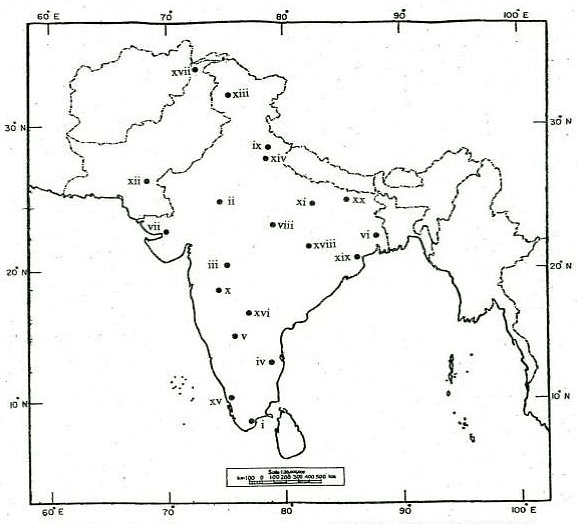

Q.1. Identify the following places marked on the map supplied to you and write a short note of about 30 words on each of them in your Question-cum-Answer Booklet. Locational hints for each of the places marked on the map are given below serial wise: (2.5 x 20 = 50)

(i) Paleolithic site.

(ii) Paleolithic Factory site.

(iii) Neolithic site.

(iv) Early and Mature Harappan site.

(v) Chalcolithic site.

(vi) Site of Coin and Seal Moulds.

(vii) Ancient Administration Centre.

(viii) Ancient Political Headquarter.

(ix) Ancient temple site.

(x) Pre and Proto Historic site.

(xi) Ancient Capital city.

(xii) Place of Shiva Temple.

(xiii) World Heritage Centre of Temple complex

(xiv) An Inscriptional site.

(xv) Place of Jain Temple.

(xvi) Largest Buddhist Monastery.

(xvii) Ancient Temple Complex.

(xviii) Place of oldest Mosque.

(xix) Temple Complex dedicated to Shiva.

(xx) Ancient Education Centre.

(i) Bhimbetka: A paleolithic site in Madhya Pradesh, known for its rock shelters and cave paintings, representing the earliest traces of human life in India.

(ii) Patne: A paleolithic factory site in Maharashtra, where stone tools and other artifacts have been found, providing evidence of early human activities.

(iii) Burzahom: A neolithic site in Jammu and Kashmir, known for its pit dwellings and evidence of early agriculture and domestication of animals.

(iv) Kalibangan: An early and mature Harappan site in Rajasthan, known for its unique grid-pattern city planning, water management system, and evidence of trade and commerce.

(v) Ahar: A chalcolithic site in Rajasthan, known for its pottery, copper artifacts, and evidence of early urbanization.

(vi) Taxila: A site of coin and seal moulds in Pakistan, which was an important centre of learning and trade during the ancient period.

(vii) Pataliputra: An ancient administration centre in Bihar, which served as the capital of various empires, including the Mauryan Empire.

(viii) Magadha: An ancient political headquarter in Bihar, which was the centre of various empires, including the Mauryan and Gupta empires.

(ix) Khajuraho: An ancient temple site in Madhya Pradesh, known for its magnificent Hindu and Jain temples, famous for their erotic sculptures.

(x) Adichanallur: A pre and proto-historic site in Tamil Nadu, known for its urn burials and evidence of early Iron Age culture.

(xi) Hampi: An ancient capital city in Karnataka, which was the centre of the Vijayanagara Empire and is famous for its ruins, temples, and monuments.

(xii) Kailasanathar Temple: A place of Shiva temple in Tamil Nadu, which is a fine example of Dravidian architecture and is adorned with intricate sculptures.

(xiii) Konark Sun Temple: A world heritage centre of temple complex in Odisha, dedicated to the sun god and known for its intricate stone carvings and architectural grandeur.

(xiv) Junagadh: An inscriptional site in Gujarat, where the Ashokan rock edicts are found, providing valuable information about the Mauryan Empire and its administration.

(xv) Palitana: A place of Jain temple in Gujarat, known for its numerous beautifully carved temples on the Shatrunjaya hills.

(xvi) Nalanda: The largest Buddhist monastery in ancient India, located in Bihar, which was a renowned centre of learning and attracted scholars from various parts of the world.

(xvii) Pattadakal: An ancient temple complex in Karnataka, known for its group of Hindu and Jain temples, showcasing a fusion of architectural styles.

(xviii) Cheraman Juma Masjid: A place of the oldest mosque in India, located in Kerala, believed to have been built during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad.

(xix) Brihadeeswarar Temple: A temple complex dedicated to Shiva in Tamil Nadu, which is an outstanding example of Chola architecture and is known for its massive size and intricate sculptures.

(xx) Vikramshila: An ancient education centre in Bihar, which was one of the most important Buddhist universities during the Pala Empire and attracted scholars from across the world.

Q.2. Answer the following:

(a) Puranas were the innovative genre of literature to popularise and revive Vedic religion. Elaborate with examples. (15 Marks)The Puranas are an important genre of ancient Indian literature, which played a significant role in popularising and reviving the Vedic religion. The word 'Purana' means 'ancient' or 'old', and these texts are a vast collection of stories, legends, myths, genealogies, and religious teachings, which were compiled over several centuries by various authors. The Puranas are considered as the fifth Veda and are classified into 18 major Puranas and 18 minor Puranas (Upapuranas).

The Puranas played a crucial role in popularising and reviving Vedic religion in the following ways:

1. Simplification of complex Vedic rituals: The Vedic religion was primarily based on complex rituals and sacrifices, which were performed by the priests, and common people had limited access to these rituals. The Puranas simplified the Vedic rituals and made them accessible to the masses. For example, the Puranas introduced the concept of pujas and prayers, which could be performed by anyone, irrespective of their caste or gender.

2. Inclusion of local deities and legends: The Puranas incorporated local deities and legends into the Vedic pantheon, which helped in the absorption of various regional and tribal religious beliefs into the Vedic religion. For instance, the worship of Lord Shiva and Vishnu, who were originally local deities, were integrated into the Vedic religion through the Puranas.

3. Creation of a universal religious narrative: The Puranas provided a universal narrative of the creation, preservation, and destruction of the universe, which helped in unifying the diverse religious beliefs and practices across the Indian subcontinent. The Puranas also established a genealogical connection between various ruling dynasties and the Vedic gods, which enhanced the legitimacy of these rulers and their patronage of Vedic religion.

4. Popularisation through storytelling: The Puranas used storytelling as an effective tool to communicate religious teachings and moral values to the masses. The stories of gods, goddesses, and heroes were narrated in a simple and engaging manner, which made them relatable and appealing to the common people. This helped in the propagation of Vedic religion and values among the masses.

5. Emphasis on devotion and personal religious experience: The Puranas emphasised the importance of devotion (Bhakti) and personal religious experience as a means to attain spiritual salvation. This shift in focus from ritualistic practices to personal devotion made Vedic religion more appealing and accessible to the masses.

Some examples of Puranas and their contribution to popularising Vedic religion are:

1. Bhagavata Purana: This Purana is devoted to Lord Vishnu and his various incarnations, particularly Krishna. It emphasises the concept of devotion (Bhakti) and provides a detailed account of Krishna's life and teachings. The stories and teachings in the Bhagavata Purana played a significant role in popularising Vedic religion and promoting the cult of Krishna.

2. Shiva Purana: This Purana is devoted to Lord Shiva and provides a detailed account of his various forms, legends, and myths. It popularised the worship of Shiva and contributed to the integration of various Shaivite sects into the Vedic religion.

3. Devi Bhagavata Purana: This Purana is devoted to the Goddess and provides a detailed account of her various forms, legends, and myths. It popularised the worship of the Goddess and contributed to the integration of various Shakta sects into the Vedic religion.

4. Vishnu Purana: This Purana is devoted to Lord Vishnu and provides a detailed account of his various incarnations, particularly Rama. It emphasises the concept of Dharma and provides a genealogical connection between various ruling dynasties and the Vedic gods.

In conclusion, the Puranas played a vital role in popularising and reviving the Vedic religion by making it more accessible and appealing to the masses. They helped in the integration of various regional and tribal religious beliefs into the Vedic religion and provided a universal narrative that unified the diverse religious practices across the Indian subcontinent.

(b) Discuss the factors that played an important role in the process of urbanisation after the Later-Vedic period. (15 Marks)

The process of urbanisation that began after the Later-Vedic period was a significant development in ancient Indian history. This urbanisation marked the transition from a predominantly rural, agricultural society to a more complex, urban society with various economic, social, and political changes. Several factors played an important role in this process, such as:

1. Geographical factors: The emergence of urban centres in the Gangetic plains, especially the region between the Ganga and Yamuna rivers, provided fertile soil and ample water resources for agricultural production. This led to a surplus of agricultural produce, which in turn supported the growth of urban centres.

2. Economic factors: The growth of trade and commerce during this period was a major catalyst for urbanisation. The use of iron tools and the knowledge of iron metallurgy led to increased agricultural production and surplus. This surplus was then traded in urban centres, leading to the growth of trade networks and marketplaces. The discovery of new trade routes, both overland and maritime, further facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and people between different regions.

3. Political factors: The emergence of large territorial states, known as Mahajanapadas, played a crucial role in the process of urbanisation. These states had a well-organised administrative system and a strong military, which helped maintain law and order and protect trade routes. The capitals of these states, such as Magadha, Kosala, and Kuru, became important urban centres that attracted people from various walks of life.

4. Social factors: The growth of urban centres led to the emergence of new social classes and professional groups, such as traders, artisans, and craftsmen. These groups formed guilds and associations for the protection of their interests and contributed to the growth of the urban economy. Additionally, the rise of heterodox sects such as Buddhism and Jainism contributed to the growth of urban centres, as they attracted followers and patrons, leading to the establishment of monasteries, educational institutions, and pilgrimage centres.

5. Cultural factors: The growth of urban centres led to significant cultural developments, such as the emergence of new art forms, literature, and architecture. The patronage of art and architecture by rulers, wealthy merchants, and religious institutions further contributed to the growth of urban centres. Famous examples of urban architectural marvels from this period include the stupas at Sanchi and Bharhut, the rock-cut caves at Ajanta and Ellora, and the universities of Nalanda and Taxila.

In conclusion, the process of urbanisation after the Later-Vedic period was a result of various interconnected factors, including geographical, economic, political, social, and cultural developments. The emergence of urban centres marked a significant shift in ancient Indian society and had lasting effects on the social, economic, and political landscape of the subcontinent.

(c) Throw light on the nature of religion and classification of gods mentioned in the Rigveda. (20 Marks)

The Rigveda is the oldest and most revered text among the four Vedas in Hinduism, believed to have been composed between 1500 and 1000 BCE. It is a collection of over 1,000 hymns and 10,000 verses organized into ten books called "Mandalas." The Rigveda lays the foundation for the Vedic religion, which later evolved into Hinduism. The nature of religion and the classification of gods can be understood by examining the content and themes of the Rigveda.

Nature of Religion in Rigveda:

1. Polytheism: The Rigveda reflects a polytheistic religious belief, with several gods and goddesses being revered and worshipped. The hymns describe and invoke various deities, each representing a natural force or aspect of life. The gods were believed to be immortal, powerful, and responsible for the well-being of humans and the order of the universe.

2. Ritualistic: The Vedic religion was highly ritualistic, with the performance of sacrifices (Yajnas) being central to religious practices. These sacrifices were conducted by priests (Brahmins) who recited hymns and offered oblations to the gods in the sacred fire (Agni). These rituals were believed to ensure the well-being of the individual, society, and the cosmos.

3. Nature-centric: The religion of Rigveda was closely connected with the natural world. Many of the hymns praise the various elements of nature like the sun, wind, fire, water, and earth. The gods were often associated with these natural phenomena, and the hymns sought their blessings for prosperity, fertility, and protection from natural calamities.

4. Moral and Ethical Values: The Rigveda also contains hymns that emphasize moral and ethical values. There is a stress on the importance of truth (Satya), righteousness (Rta), and adherence to the cosmic order (Dharma). It also highlights the virtues of generosity, hospitality, and compassion.

Classification of Gods in Rigveda:

The gods mentioned in the Rigveda can be broadly classified into three categories:

1. Celestial Deities: These gods are associated with the sky and celestial phenomena. They include:

(a) Indra: The god of thunder, lightning, and rain, Indra is the most celebrated and invoked deity in the Rigveda. He is the king of the gods and is hailed as the destroyer of the demon Vritra, who withheld the waters.

(b) Varuna: The god of the sky, water, and cosmic order (Rta), Varuna is considered the guardian of moral laws and is often invoked alongside Mitra.

(c) Surya: The Sun god, Surya is revered for giving light and life to the world. He is often associated with the dawn goddess Ushas.

2. Atmospheric Deities: These gods are associated with the atmosphere and weather phenomena. They include:

(i) Vayu: The god of wind, Vayu is praised for his power and speed. He is also associated with the breath and life force (Prana) in living beings.

(ii) Parjanya: The god of rain, Parjanya is invoked for good rainfall and the fertility of the land.

(ii) Agni: The god of fire, Agni is one of the most important deities in the Rigveda. He is the mediator between humans and gods, carrying the offerings of sacrifices to the gods.

3. Terrestrial Deities: These gods are associated with the earth and its various aspects. They include:

(i) Prithvi: The Earth goddess, Prithvi is praised for her fertility and abundance. She is often invoked alongside the sky god Dyaus.

(ii) Yama: The god of death and the underworld, Yama is considered the first mortal who died and paved the way for others to follow. He is also associated with moral judgment and the afterlife.

(ii) Saraswati: The goddess of rivers and knowledge, Saraswati is invoked for learning, wisdom, and the life-giving properties of water.

In conclusion, the Rigveda presents a complex and diverse picture of religious beliefs and practices in ancient India. The nature of religion was polytheistic, ritualistic, nature-centric, and focused on moral values. The gods mentioned in the Rigveda can be classified into celestial, atmospheric, and terrestrial deities, each representing different aspects of the natural world and human life.

Q.3. Answer the following:

(a) Evaluate the significant political features of the Post Mauryan Northern India. What are the main sources of it? (15 Marks)

The Post-Mauryan period in Northern India (circa 200 BCE to 300 CE) was marked by the emergence of various regional powers and intense political, economic, and cultural transformations. This period saw the decline of the Mauryan dynasty and the rise of several influential regional powers, including the Sunga, Kanva, and the Kushana empires, as well as the Satavahana dynasty in the Deccan.

Significant Political Features of Post-Mauryan Northern India:

1. Fragmentation of Political Power: The decline of the Mauryan Empire led to political fragmentation, with many smaller kingdoms and republics emerging in Northern India. These regional powers often competed with each other for territory, resources, and influence.

2. Emergence of Regional Powers: Prominent regional powers in Post-Mauryan Northern India included the Shunga dynasty, the Kanva dynasty, and the Kushana Empire. The Shungas and Kanvas were Brahmin dynasties that ruled over the Magadha region, while the Kushanas established a vast empire that extended from Central Asia to Northern India.

3. Indo-Greek Rule: The Post-Mauryan period also saw the extension of the Indo-Greek rule in Northwestern India. The Indo-Greek rulers, such as Menander, introduced Hellenistic art, architecture, and coinage to Northern India.

4. Foreign Invasions: The Post-Mauryan period was marked by a series of invasions by various foreign powers, including the Sakas, Pahlavas, and Kushanas. These invasions led to the establishment of new political and cultural contacts between India and the wider world.

5. Synthesis of Cultures: The interaction of various cultures in Post-Mauryan Northern India led to a synthesis of Indian and foreign elements in art, architecture, religion, and other aspects of culture. For example, the Gandhara School of Art, which flourished during the Kushana period, was characterized by a blend of Indian and Hellenistic artistic traditions.

Main Sources of Post-Mauryan Northern India:

1. Literary Sources: Important literary sources for the Post-Mauryan period include the works of Patanjali, such as the Mahabhashya, and the works of the famous Sanskrit playwright Kalidasa. Buddhist literature, such as the Divyavadana and the Milindapanho, also provide valuable information about this period.

2. Inscriptions: Inscriptions from the Post-Mauryan period, such as the Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela, the Junagarh rock inscription of Rudradaman, and the numerous inscriptions of the Kushana rulers, provide crucial information about the political and cultural developments of this period.

3. Numismatic Evidence: Coins from the Post-Mauryan period, such as those issued by the Indo-Greek rulers, the Sakas, the Pahlavas, and the Kushanas, provide important evidence for the political, economic, and cultural history of this period.

4. Archaeological Evidence: Excavations at various sites, such as Sanchi, Bharhut, Mathura, and Taxila, have revealed important information about the art, architecture, and everyday life of the people in Post-Mauryan Northern India.

In conclusion, the Post-Mauryan period in Northern India was characterized by political fragmentation and the emergence of regional powers, as well as significant cultural transformations and interactions between Indian and foreign elements. The main sources of information for this period include literary works, inscriptions, numismatic evidence, and archaeological findings, which together provide a comprehensive understanding of the political, economic, and cultural landscape of Post-Mauryan Northern India.

(b) A number of scholars considered Alexander as 'The Great', although long term impacts of Alexander's invasion on India need to be re-evaluated. Comment. (15 Marks)

Alexander the Great is widely regarded as one of the most successful military leaders in history, conquering vast territories across the ancient world. His invasion of India in 326 BCE is a significant event in Indian history, and while it did have short-term consequences, the long-term impacts of his invasion on India need to be re-evaluated.

(i) To begin with, it is essential to recognize that Alexander's invasion of India was brief and limited in scope. He only managed to conquer the northwestern region of India, including present-day Punjab and parts of Pakistan. Alexander's army faced fierce resistance from Indian rulers, such as King Porus, and his troops were exhausted after years of continuous warfare. This led to Alexander's decision to return to Babylon, leaving behind a relatively small imprint on Indian history.

(ii) However, Alexander's invasion did leave some short-term consequences, including the establishment of Greek settlements in the conquered territories. These settlements facilitated cultural exchanges between the Greeks and the local population, leading to the fusion of Greek and Indian art, as seen in the Gandhara school of art. This school of art is known for its unique amalgamation of Greek and Indian elements, particularly in the depiction of the Buddha.

(iii) Additionally, Alexander's invasion led to increased trade and diplomatic relations between India and the Hellenistic world, as evidenced by the presence of Indian ambassadors at the courts of Hellenistic rulers, such as Seleucus Nicator. This increased interaction contributed to the spread of Indian ideas and knowledge to the West, including the fields of mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.

(iv) Despite these short-term consequences, the long-term impacts of Alexander's invasion on India are less significant. Alexander's empire disintegrated soon after his death, and the Greek settlements in India were eventually assimilated into the Mauryan Empire under Chandragupta Maurya. This marked the beginning of a new chapter in Indian history, which saw the rise of one of the most extensive and powerful empires in ancient India.

(v) Moreover, the cultural exchanges initiated by Alexander's invasion were not sustained over the long term. The Gandhara school of art, for example, was short-lived and eventually gave way to other Indian artistic traditions, such as the Mathura and Gupta schools of art. Furthermore, the impact of Greek philosophy and ideas on Indian intellectual thought was limited, as Indian philosophical systems like Vedanta, Samkhya, and Nyaya continued to develop independently.

In conclusion, while Alexander the Great's invasion of India had some short-term consequences in terms of cultural exchanges, increased trade, and diplomatic relations, its long-term impacts on India are relatively limited. The invasion itself was short-lived, and its effects were quickly overshadowed by the rise of the Mauryan Empire and the continued development of Indian cultural and intellectual traditions. Thus, the significance of Alexander's invasion in Indian history needs to be re-evaluated, as it was not as transformative or long-lasting as often assumed.

(c) Discuss the salient features of cultural traditions of South India as reflected in Sangam Literature. (20 Marks)

Sangam Literature refers to a large body of classical Tamil literature created between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE. It is a significant source of information on the culture, society, and history of ancient South India, particularly the Tamil-speaking regions. The literature is comprised of over 2,000 poems and 30,000 lines of poetry, composed by over 470 poets. The three major anthologies of Sangam Literature are Ettuthokai, Pattuppattu, and Pathinenkilkanakku.

The salient features of cultural traditions of South India as reflected in Sangam Literature can be discussed under the following headings:

1. Social Structure: Sangam Literature reveals that ancient South Indian society was characterized by a hierarchical structure, with four main classes or castes - Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (rulers and warriors), Vaisyas (merchants and traders), and Shudras (laborers and servants). However, the caste system was relatively flexible, and occupational mobility was possible.

2. Polity and Administration: Ancient South Indian polity was organized into city-states, with each city ruled by a king or chieftain. The administration was carried out by a council of ministers and officials, who advised and assisted the king. The literature also mentions the existence of village assemblies called 'Sabhas' and 'Urainadai,' which played a role in local governance.

3. Economy and Trade: The economy of ancient South India was primarily agrarian, with agriculture being the main occupation. The region was known for its rich and fertile land, with paddy cultivation being the primary crop. Trade and commerce were also significant aspects of the economy, with internal and external trade flourishing. The literature mentions the existence of trade guilds and associations, which facilitated trade with other regions, particularly the Roman Empire.

4. Religion and Philosophy: Sangam Literature reflects the religious and philosophical beliefs of the people of South India. The major religions in the region were Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. The literature contains references to various Hindu deities, such as Murugan, Shiva, and Vishnu, and the worship of nature, ancestors, and spirits. The importance of moral values, righteous conduct, and the consequences of one's actions are also emphasized in the literature, reflecting the influence of Buddhism and Jainism on the society.

5. Language and Literature: The Tamil language was the primary medium of expression in Sangam Literature, which attests to its antiquity and richness. The literature is characterized by its unique poetic style, with complex metaphors, similes, and allusions. The poems are classified into two main categories - 'Aham' (love and personal relationships) and 'Puram' (war, politics, and social life).

6. Art, Music, and Dance: Sangam Literature provides glimpses of the art, music, and dance forms prevalent in ancient South India. The literature mentions various musical instruments, such as the yazh (a stringed instrument), maddalam (a percussion instrument), and kuzhal (a wind instrument). Dance forms like 'Koothu' and 'Kadakam' are also mentioned, indicating the importance of performing arts in the cultural life of the people.

7. Architecture and Sculpture: The Sangam Literature provides limited information on architecture and sculpture, as it primarily focuses on the natural beauty of the landscape. However, there are references to the existence of palaces, forts, and temples, suggesting the presence of an architectural tradition. The literature also mentions various types of sculptures, such as stone, wood, and metal, indicating the skill of the artisans of the time.

In conclusion, Sangam Literature is an invaluable source of information on the cultural traditions of ancient South India. It provides insights into various aspects of the society, such as social structure, polity, economy, religion, language, literature, art, music, dance, architecture, and sculpture. The literature reflects the rich and diverse cultural heritage of the region and continues to inspire and influence modern Tamil literature and culture.

Q.4. Answer the following:

(a) 'Sanskrit literature of classical Gupta Age set standards for the early medieval India'. Evaluate the statement with representative examples. (15 Marks)

The Gupta Age, also known as the Golden Age of India, lasted from around the 4th to 6th centuries CE. During this period, India witnessed a remarkable growth in various fields, including science, mathematics, art, and literature. The Sanskrit literature produced during the classical Gupta Age played a significant role in setting standards for early medieval India in various aspects. This statement can be evaluated by examining the notable works and their impact on society, culture, and education.

1. Poetry and Drama: The Gupta Age witnessed an extraordinary development in the field of poetry and drama. Some of the most celebrated poets and playwrights of the time, such as Kalidasa, Bhasa, Bharavi, and Bhavabhuti, contributed immensely to enriching Sanskrit literature. Kalidasa's works like Abhijnanasakuntalam, Raghuvamsa, and Meghaduta are considered the epitomes of classical literature. The themes, emotions, and expressions in these works became the standard for subsequent poets and playwrights.

2. Epics and Puranas: The Gupta Age saw the final compilation and redaction of the great Indian epics Mahabharata and Ramayana. These epics provided a treasure trove of stories, values, and wisdom that shaped the cultural and social fabric of early medieval India. The Puranas, which are encyclopedic texts containing mythology, history, and genealogy, also reached their final form during this period. The Puranas standardized religious and social practices, imbuing them with authority and sanctity.

3. Grammar and Linguistics: The study of grammar and linguistics reached its zenith during the Gupta Age. The famous grammarian, Panini, composed his monumental work Ashtadhyayi, which laid down the rules of classical Sanskrit grammar. This work became the foundation for the study of linguistics not only in India but also in the West. Patanjali's Mahabhashya, a commentary on Panini's grammar, further refined and systematized the study of Sanskrit grammar.

4. Philosophy and Religion: The Gupta Age saw the development of several philosophical and religious texts that shaped the intellectual discourse of early medieval India. The key philosophical systems like Vedanta, Nyaya, and Mimamsa were systematized and their texts were codified. The Brahma Sutras by Badarayana, the founder of the Vedanta system, and the Nyaya Sutras by Gautama, the founder of the Nyaya system, are examples of such codification. The Gupta Age also saw the production of the Bhagavad Gita, which synthesized various strands of Hindu philosophy and became a central text for Hinduism in the subsequent period.

5. Science and Mathematics: The Gupta Age contributed significantly to the fields of science and mathematics, with texts like Aryabhatiya by Aryabhata and Surya Siddhanta. These works laid the foundation for the study of astronomy, mathematics, and astrology in the subsequent period. Aryabhata's works on astronomy and mathematics, including the concept of zero, greatly influenced the development of these fields in early medieval India.

In conclusion, the Sanskrit literature of the classical Gupta Age set the standards for early medieval India in various fields, such as poetry, drama, epics, Puranas, grammar, linguistics, philosophy, religion, and science. The works produced during this period provided a strong foundation for the development of Indian culture, society, and education in the subsequent centuries. Thus, the Gupta Age played a pivotal role in shaping the intellectual and cultural landscape of early medieval India.

(b) Trace and identify the changing pattern of Tantrism in Ancient India with examples. (15 Marks)

Tantrism, also known as Tantra, is a complex and multifaceted religious and spiritual tradition that originated in ancient India. It has played a significant role in shaping the religious, cultural, and social landscape of South Asia. The development of Tantrism in ancient India can be traced and identified through various phases and patterns, which I will discuss below.

1. Early Origins: The beginnings of Tantrism can be traced back to the Vedic period (c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE). The seeds of Tantra can be found in the Atharva Veda, which contains various magical spells, rituals, and incantations. The early Vedic tradition also witnessed the emergence of the cult of Shakti, the female cosmic power, which later became an integral part of Tantra.

2. Emergence of Tantric Texts: The development of Tantrism gained momentum during the Gupta period (c. 320 - c. 550 CE). It was during this period that various Tantric texts, known as Agamas and Tantras, started appearing. These texts provided the theoretical and practical framework for the Tantric practices that evolved during this period. Examples of early Tantric texts include the Nisvasa Tattva Samhita, the Kula-Chudamani Tantra, and the Kularnava Tantra.

3. Integration with Mainstream Religion: During the early medieval period (c. 600 - c. 1200 CE), Tantrism started to integrate with mainstream Hinduism and Buddhism. In Hinduism, the worship of Shiva and Shakti became increasingly popular, leading to the emergence of Shaivism and Shaktism as major sects. In Buddhism, Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism emerged as a distinct tradition that incorporated Tantric practices and rituals. Examples of Tantric integration with mainstream religion include the worship of Bhairava, a fierce form of Shiva, and the Chakrasamvara Tantra in Buddhism.

4. Development of Regional Tantric Traditions: Tantrism continued to evolve and diversify during the late medieval period (c. 1200 - c. 1700 CE). Various regional Tantric traditions emerged, which reflected the local cultural and religious milieu. For example, in Kashmir, the tradition of Krama and Trika Shaivism developed, while in Bengal, the tradition of Bauls and Sahajayana Buddhism emerged. The worship of local deities, such as Kali in Bengal and Bhairavi in Assam, also became integrated with Tantric practices.

5. Role in Political and Social Life: Tantrism played a significant role in shaping the political and social life of ancient India. Many ruling dynasties, such as the Pala Dynasty in eastern India and the Chola Dynasty in southern India, patronized and supported Tantric practices. Kings and queens were often initiated into Tantric traditions and performed rituals to ensure their success and well-being. Tantric practices also influenced various aspects of social life, such as art, architecture, and literature.

In conclusion, the changing pattern of Tantrism in ancient India can be identified through its early origins in the Vedic period, the emergence of Tantric texts during the Gupta period, integration with mainstream religion during the early medieval period, development of regional Tantric traditions during the late medieval period, and its influence on political and social life throughout ancient India. Examples of these patterns can be seen in the various Tantric texts, religious sects, and cultural practices that emerged and evolved over time.

(c) Describe the evolution and development of regional temple architecture of South India with special reference to Pallavas. (20 Marks)

The temple architecture of South India evolved and developed over a long period under various dynasties that ruled the region. Among these dynasties, the Pallavas played a significant role in shaping the temple architecture of South India. The Pallava dynasty ruled the region of modern-day Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu between the 4th and 9th centuries CE. They were great patrons of art and architecture, and their reign witnessed the development of various styles of temple architecture.

The development of regional temple architecture under the Pallavas can be studied under the following phases:

1. Early Phase (610-690 CE): The early phase of Pallava temple architecture is marked by the construction of rock-cut temples, also known as cave temples. These temples were excavated out of solid rocks, and their walls were adorned with beautiful sculptures and inscriptions. The most famous examples of rock-cut temples from this phase are the Mandagapattu temples, which were built by King Mahendravarman I. Other examples include the Mamandur cave temples and the Mahishasuramardini cave temple in Mahabalipuram.

2. Middle Phase (690-740 CE): The middle phase of Pallava temple architecture saw the construction of monolithic temples, also known as rathas. These temples were carved out of a single rock and were shaped like chariots. The most famous example of monolithic temples is the Pancha Rathas at Mahabalipuram, built during the reign of King Narasimhavarman I. Each of these five rathas is dedicated to a different deity and is named after the Pandavas from the Mahabharata.

3. Late Phase (740-900 CE): The late phase of Pallava temple architecture is characterized by the construction of structural temples made of stone. These temples were built using the Dravidian style of architecture, which typically featured a square sanctum sanctorum, a circumambulatory passage, and a pyramidal vimana or tower above the sanctum. The most famous example of a structural temple from this phase is the Kailasanathar temple at Kanchipuram, built by King Rajasimha (Narasimhavarman II). This temple is dedicated to Lord Shiva and is considered the finest example of Pallava architecture. Other examples include the Vaikuntha Perumal temple at Kanchipuram and the Shore temple at Mahabalipuram.

Some key features of the Pallava temple architecture include:

1. Elaborate sculptures: The Pallava temples are adorned with intricate sculptures depicting various deities, mythical creatures, and scenes from Hindu mythology. The relief sculpture of Arjuna's Penance at Mahabalipuram is one of the finest examples of Pallava art.

2. Inscriptions: The Pallava temples feature inscriptions in Sanskrit and Tamil, which provide valuable information about the rulers, their achievements, and the socio-economic conditions of the times.

3. Gateways (gopurams): The structural temples built during the late Pallava period featured elaborate gateways known as gopurams. These gopurams were adorned with intricate sculptures and served as the entrance to the temple complex.

4. Combination of styles: The Pallava temple architecture reflects a combination of various architectural styles, including the Dravidian, Gupta, and Buddhist styles. This amalgamation of styles showcases the cultural diversity and rich artistic heritage of South India during the Pallava period.

In conclusion, the Pallava dynasty played a crucial role in the evolution and development of regional temple architecture in South India. Their contributions to the field of art and architecture, especially in the form of rock-cut temples, monolithic rathas, and structural temples, have left a lasting impact on the cultural heritage of the region.

|

367 videos|995 docs

|