Indian Penal Code | Additional Study Material for CLAT PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Elements of Crime |

|

| Kinds of Punishments |

|

| General Exceptions |

|

| Mistake Of Law: |

|

The First Law Commission was appointed in India in 1835. The commission had four members. Lord T.B. Macaulay was the Chairman of the First Law Commission. It was directed to prepare a draft of penal code for India which it submitted it to the Government in 1837. This draft was enacted into law in 1860 by the Legislative Council. It received the assent of the Governor General on 6th October, 1860 and came into force on 1st January,1862 in British India. By this enactment Muslim Criminal law was completely abolished and a uniform penal law for India was introduced. However, the princely states continued to follow their own legal system until 1940. The state of Jammu & Kashmir has its own Ranbir Penal Code which in itself is based on IPC. After partition, India inherited the legal system implemented by the British.

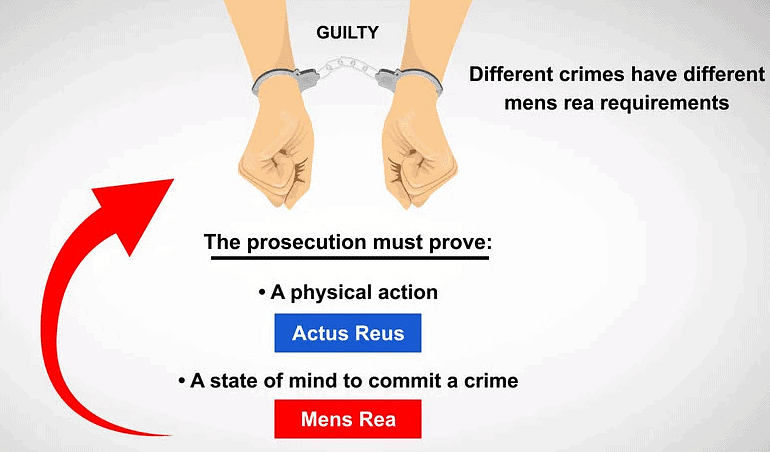

Elements of Crime

The fundamental principle of penal liability is contained in the maxim" actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea;. The maxim means an act does not amount to a crime unless it is done with a guilty intention. In other words the act alone does not amount to guilt, it must be accompanied by a guilty

mind. The intent and the act must both concur to constitute the crime. Thus there are two essential conditions of criminal liability. They are:-

(1) Actus reus;

(2) Mens rea

Elements of Crime

Elements of Crime

(1) Actus reus (Result of human conduct)

Actus reus is the first essential element or ingredient of a crime. An act is any event which is subject to the control of human will. An act is a conscious movement. It is the conduct which results from the operation of will. "Actus reus" refers to the result of human conduct which the law seeks to prevent. If any human conduct (actus) is not prohibited by law, the act or conduct will not be termed as a crime. A person who comfits such an act is not liable for a crime. Any movement of the body which is not a consequence of the determination of the will is not an act. Thus involuntary actions will not become criminal act. If a person who suffers from sleep disorder and he sets fire to a house during his sleepwalk, he will not be liable under criminal law.

Actus reus may be either Positive or Negative.

Example 1 : X'; shoots ;Y and kills him. It is a positive actus reus.

It is an example of ‘positive’ actus reus.

Example 2: The mother of a child does not feed him and causes the death of the child by starvation. Here, actus reus is negative or omission to act.

It is an example of ‘negative’ kind of actus reus.

In order to be liable for crime the act or omission should be one prohibited by law.

More illustrations of Negative kind of ‘actus reus’.

(i) A, who is having sufficient means, failed tohelp a starving man. The man dies due tostarvation. Is A criminally liable for death of the starving

man ?

No. A is under no obligation to feed the starving man and his omission is not prohibited by law. A has not committed any crime.

(ii)N, who knows swimming , failed to save the life a drowning child in a swimming pool and the child died as a result of the omission.

The omission is not prohibited by law and A; is not liable for crime. However, if A was a so appointed to save the drowning persons, then the omission to act would have been a crime.

(iii) A is a Jail warden. He failed, to supply food to the prisoners in the jail and several prisoners died due to starvation. The jail warden is liable for murder as he was under duty to provide food to the prisoners and thus violated a prohibited omission.

2. Mens rea (Guilty Mind)

A prohibited act will become a crime only when it is accompanied by a guilty state of mind. The mind must know that the act it is asking the body to commit is prohibited by law and thus will be at fault; before any crime can be committed. An act or omission alone is not sufficient to constitute a crime. Thus we may say,

Crime = Prohibited act + Guilty mind.

In England and India the general rule relating to criminal liability is based on the maxim actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea that an act is not a crime unless it is done with guilty mind

Therefore, if the mental element of anyconduct alleged to be a crime is proved tohave been absent in any given case, the crime so defined is not committed, or nothing amounts to a crime which does not satisfy that definition.

Exceptions to ‘mens rea’:

There are certain enactments which define offences without mentioning the necessity of mens rea.

1. Bigamy

2. Public Nuisance

3. Revenue Acts

4. Criminal cases on summary trial

In those statutes offences are defined in absolute terms. The Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1947, the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 1954, the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act,1985 etc., are examples of such enactments.

When an offence is defined in absolute terms i.e. without mentioning the necessity of mens rea, the question that would normally arise is:

Whether the courts can read in between lines the necessary mens rea?

In former times it was thought that the legislature was not competent to over-ride the established rules of common law. Accordingto this view, even if the necessity of mens rea is not expressly mentioned in a particular statute, the judges should read in between lines to find out the necessary mens rea. In other words the necessity of mens rea should be taken as granted. Thus even if the offence is defined without mentioning the necessity of mens rea, the courts used to acquit the accused in the absence of guilty mind.

Kinds of Punishments

1) Death sentence (Capital Punishment)

2) Imprisonment for life

3) Imprisonment - simple and rigorous

4) Forfeiture of property

5) Fine

Commutation of Sentence of imprisonment for life - It empowers the appropriate govt to commute the sentence of a Life imprisonment after he already in jail since 14 years.

General Exceptions

There are certain general defences under the criminal law which accused can plead before the court to prove his innocence. The general exceptions are contained in sections 75-106 and these have the effect of converting an offence into a non-offence. In law, the burden of proving that one has committed an offence is always on the person who has made the charge or the accuser and not on the accused; but in this case if the accused pleads non-guilty taking advantage of these exceptions, then the burden of proof will lie on him.

Example

A, a soldier, fires on a mob by the order of his superior officer in conformity with the commands of the law. Here the onus is on A to prove that the act

done by him was by the order of his superior and thus he is innocent.

The General Exceptions mainly are:

i) Mistake of Fact … Ss – 76, 79

ii) Judicial acts …. Ss- 77,78

iii) Accident ... S-80

iv) Absence of criminal intent … Ss-81- 86, 92-94

v) Consent …. Ss 87- 91

vi) Trifling acts …… S – 95

vii) Private Defence …. Ss-96 – 106

These can be called either

1. Excusable

2. Justifiable

1) Act done by a person bound or by mistake of fact believing himself bound by law

Here a person is excused who has done whatby law is an offence, under a misconception of facts, leading him to believe in good faith that he was commanded by law to do it.

Example- A an officer of a court of Justice, being ordered by that Court to arrest Y and, and, after due enquiring, believing Z to be Y, arrests Z. A has committed no offence.

Principle: Nothing is an offence which is done by a person who is, or who by reason of a mistake of fact and not by reason of a mistake of law in good faith believes himself to be bound by law to do it.

Example: A police-officer came to Bombay from village with a warrant to arrest a person. After reasonable inquiries and on well- founded suspicion he arrested A, a shopkeeper under the warrant, believing in good faith that he was the person to be arrested. A, field a complaint-against the police officer for wrongful confinement. The police officer is not guilty because he was acting under belief that the person he arrested was the one against whom the warrant was issued.

2) Act of Judge when acting Judicially

Under this section a Judge is exempted not only in those cases in which he proceeds irregularly in the exercise of a power which the law gives him, but also in cases where he, in good faith, exceeds his jurisdiction and her no lawful powers.

Principle- Nothing is an offence which is done by a Judge when acting judicially in the exercise of any power which is, or which in good faith he believes to be, given to him.

3) Act done pursuant to the judgment or order of court

Principle: Nothing which is done in pursuance of or which is warranted by the judgment or order of, a court of justice, if done whilst such judgment or order remains in force, is an offence, notwithstanding the court may have had no jurisdiction to pass such judgment or order, provided the person doing the act in good faith believes that the court had such jurisdiction.

4)Act done by a person justified or by mistake of fact believing himself justified by law.

Principle: Nothing is an offence which is done by any person who is justified by law, or who by reason of a mistake of fact and not by reason of a mistake of Law in good faith believes himself to be justified by Law in doing it.

Example: A sees Z commit What appears to A to be a murder, A, in the exercise to the best of his judgement exerted in good faith, of the power which the Law gives to all persons of apprehending murderers

Factual Situation – 1

A, a constable of the National volunteer corps in obedience to the orders of a superior officer fired a gun and shot a woman inside the tent

in which gambling was going on and no violent mob had gathered there.

Here the constable will be guilty of the offence of murder. The order of the superior was unlawful and obedience to an unlawful order does not excuse the person who commits and offence in obedience of such an order.

Factual Situation – 2

P a police officers after reasonable inquiry arrested ‘B’ who was not involved in any offence.

Here, P is entitled to claim the defence of justifiable mistake because he had arrested B after making reasonable inquiry P did not act negligently but arrested B in good faith thinking himself to be justified in doing so.

Mistake Of Law:

A mistake of Law happens when a party having full knowledge of the facts comes to an erroneous conclusion as to their legal effect. Mistake in point of Law in criminal cases is nodefence. The maxim ignorantia juris non excusat (ignorance of law excuses no one) in its application to criminal offences, admits of no exception, not even in the case of a foreigner who cannot reasonably be supposed in fact to know the law of the land. It is indeed a legal fiction to suppose that everyone knows the law of the land. It is also supported by the maxim ‘Ignorantia scire tenetur not excusat’ (i.e. ignorance of those things which one is bound to know does not excuse).

Mistake of fact and Mistake of Law.

Ignorantia facti excusat, ignorantia legis neminem excusat is a well known maxim of criminal law. It means ignorance of fact is an excuse; ignorance of law is no excuse. A mistake of fact consists is unconsciousness, ignorance or forgetfulness of a fact, past or present and which is material to the transaction. Defence of mistake of fact cannot be pleaded where an act is clearly a wrong in itself, and a person, under a mistaken impression as to the facts which render it criminal, commits that act, he will be guilty of a criminal offence. Thus burglar cannot escape punishment by saying that he entered a wrong house by mistake as he wanted to commit theft in some other house, nor can a murderer be heard to say that the deceased was not his intended victim. In either case mistake of fact is not excuse.

5) Accident in doing a lawful Act.

Under this the doer of an innocent or lawful act in an innocent or lawful manner and without any criminal intention or knowledge from any unforeseen evil result that may from accident or misfortune.

Example:

A is at work with a hatchet, the head flies off and kills a man who is standing by, Here if there was no want of proper caution on the part of A, his act is excusable and not an offence.

Principle: Nothing is an offence which is done by accident or misfortune, and without any criminal intention or knowledge in the doing of a lawful act in a lawful manner by lawful means and with proper care and caution

Factual situation: A big party consisting of some hundred men went out for sheeting pigs. A boar rushed towards P, one of the member who fired at the boar, but he missed boar and the struck the leg of a member of the party. Here P is not guilty because the death was caused by accident and was not the result of rash or negligent shooting.

6) Act likely to cause harm but done without

criminal intent and to prevent other harm.

An act which would otherwise be a crime may in some cases be excused if the person accused can show that it was done only in order to avoid consequences which could not otherwise be avoided. Thus, there must be a situation in which the accused is confronted with a grave danger and he has no choice but to commit the lesser harm, may be even to an innocent person in order to avoid the greater

harm. Here the choice is between the two evils and the accused rightly chooses the lesser one.

Example:

A, in a great fire pulls down houses in order to prevent the conflagration from spreading. He does this with the intention in good faith of saving human life or property. Here if it be found that the harm to be prevented was of such a nature and so imminent as to excuse A’s act, A is not guilty of the offence.

Principle: Nothing is an offence merely by reason of its being done with the knowledge that it is likely to cause harm, if it be done without any criminal intention to cause harm, and in good faith for the purpose of preventing or avoiding other harm to person or property.

Factual Situation: A bargeman threw the goods of ‘P’ out of a barge in order to lighten the barge in a storm and for the safety of the passengers.

Here not only the bargeman but any passenger would be justified in taking any such action for the safety of the passengers and it would be immaterial that the bargeman had overloaded the barge.

7) Act of a person of unsound Mind

Under this a person is exonerated from liability for doing an act on the ground of unsoundness of mind if he, at the time of doing the act, is either incapable of knowing.

1) the nature of the act, or

2) that he is doing what is either wrong or contrary to law

There are four kinds of persons who may be said to be non compos mentis (not of sound mind):

1) an idiot

2) one made non compos by illness

3) a lunatic or a mad man

4) one who is drunk (intoxication against one’s will)

Example: ‘A’ killed his three infant grand daughters with a handle of a grinding stone and he did not try to conceal the body of victims, nor he attempted to evade law by destroying the evidence of crime and he made no preparation for killing the three kids. It shows that he was of unsound mind at the time of commission of crime.

Principle: Nothing is an offence which is done by a person who at the time of doing it, by reason of unsoundness of mind, is incapable of knowing the nature of the act, or that he is doing what is either wrong or contrary to law.

Factual Situation:

Ram Lal killed his 8 years old boy and concealed his dead body so that no one can search the body. After destroying the evidence of crime he ran away from the place of incident. The doctors report showed that he was a case of epilepsy with retarded mental faculty so as to put him in the category of severe sub-normality

Here Ram Lal would be guilty of murder because his running away from the place of incident after destroying all the evidence of crime clearly shows that he was conscious of the fact which was enough to defeat the plea of insanity.

8) Act of a person incapable of judgement by reason of intoxication caused against his will.

Under this a person will be exonerated from liability for doing an act which in a state of intoxication if he at the time of doing it, by reason of intoxication, was

1) incapable of knowing the nature of the act,

or

2) that he was doing what was either wrong or contrary to law Provided that the thing which intoxicated him was administered to him without-his

knowledge or against his will.

Principle: Nothing is an offence if the person who at the time of doing it, is by reason of intoxication, incapable of knowing the nature of the act or that what he is doing is either wrong or contrary to law, provided the thing which intoxicated him was administered to him without his knowledge or against his will.

Factual Situation: Mohan Das got drunk of his own volition and on his way back home he assaulted a policeman. He is prosecuted for intimidating a public servant. Here, Mohan Das would be liable for punishment for interfering with the discharge of duties by a public servant. He has been intoxicated voluntarily. He can’t take the defence of intoxication to avoid liability.

Right Of Private Defence Of Accused:

Sections 96 to 106 of IPC deals with Right of Private defence. A person has all right to protect his body and property as well as the body and property of other person from any attack or aggression which endangers his own life or property or that of other person. The most important thing about this right of self defence is that it must be exercised very reasonably and cautiously. It means no more harm should be caused to the aggressor as is necessary to protect one’s own or other’s body and property. So, if you shoot a thief who has parted with the stolen goods and who is on a run to save himself, you may be charged for murder and your plea of self defence may not work. This is because, you have exceeded the right of private defence. Following points should be kept in mind while solving a question on legal reasoning based upon the concept of this exception-

1) Right of private defence is a general exception because one may not be punished even for killing another person, if it is done in valid exercise of the right of self defence.

2) This right is available against an act which reasonably cause apprehension of death or grievous hurt or rape or kidnapping or wrongful confinement of any person.

3) In case of property, this right is available against theft, robbery, mischief by fire, house- breaking etc., of any person.

4) No right of private defence if there is sufficient time to take recourse of public authorities e.g. police.

5) Aggressor or one who attacks has no right of private defence. There is no right of private defence in retaliation or revenge.

6) Right of private defence extends to causing death of the aggressor only in the case when there is a reasonable apprehension of death, grievous hurt, rape, kidnapping or abduction and wrongful confinement of the body or person.

7) One may also cause death of the aggressor where a reasonable apprehension of death or grievous hurt arises from an act of or attempt of robbery, house breaking by night, mischief by fire, theft or house trespass.

8) The harm or injury inflicted by the person on the aggressor must not exceed the danger orthreat posed by his act. One can’t kill a

pickpocket for stealing his purse unless there is an apprehension of death or grievous hurt from a weapon in his hand.

Thus, Right of private defence is absolutely necessary. While the Government is responsible for protecting its citizen, yet it cannot effectuate safety and security unless this right is granted to its citizens. The vigilance of the Magistrate can never make up for vigilance of each individual on his own

behalf.

Legal Principle: For purpose of exercising right of private defence physical or mental capacity of attacker is no bar.

Factual Situation: Robin in his madness attempts to kill Shabana. Shabana in order to save himself hits Robin with iron rod.

a) Shabana has right of private defence though Robin is mad

b) Both Robin and Shabana are guilty of no offence

c) Shabana has no right of private defence since Robin is mad

d) Shabana guilty of inflicting grievous injury on Robin

The correct answer is (a).

Legal Principles:

(I) Any person may use reasonable force in order to protect his property or person.

(II) However, the force employed must be proportionate to the apprehended danger.

Factual Situation: Ravi was walking on a lonely road. Maniyan came with a knife and said to Ravi, “Your life or your purse”. Ravi pulled out his revolver. On seeing it, Maniyan ran. Ravi shot Maniyan on his legs.

Answers:

a) Ravi will not be punished as there was danger to his property.

b) Ravi will not be punished as the force he used was proportionate to the apprehended injury.

c) Ravi will be punished as the force employed was disproportionate to the apprehended injury.

d) As Maniyan ran to escape there was no longer a threat to Ravi’s property. So Ravi will be punished.

The correct answer shall be (d). You can appreciate (c) to be a close option but, once Mr. Maniyan ran to escape there is not at all any apprehended danger. So, when there is no threat to a property or body, no right of private defence available.

Legal Principle: One has right to defend his life and property against criminal harm provided it is not possible to approach public authorities and

more harm than is necessary has not been caused to avert the danger.

Factual Situation: The farm of X on outskirts of the Delhi was attacked by a gang of armed robbers. X without informing the police, at first warned the

robbers by firing in the air. As they were fleeing from the farm, he fired and killed one of them. At the trial-

I. X can avail the right of private defence as he was defending his life and property.

II. X cannot avail the right as he failed to inform the police.

III. X cannot avail the right as he caused more harm than was necessary to ward off the danger.

IV. X can avail of the right as at first he only fired in the air.

a) I and IV b) II only

c) II and III d) IV only

Answer to this question is of course (c). This is because X has failed to take recourse to the public authorities i.e., police. Further, he kills a robber while he was fleeing away. It means there was no apprehension of death or grievous hurt to him.

Example 9

W on returning home late after work was accosted by an armed vagabond who tried to rob her purse and valuables at knife point. W raised an alarm but was unsuccessful in obtaining help. In the ensuing struggle W snatched the knife from the brigand and killed him. At the trial W –

I. Can claim the right of private defence as she was defending her life and property.

II. Can claim private defence as she tried to obtain help but could not approach public authorities.

III. Cannot claim private defence as to defend a few valuables a person cannot be killed.

IV. Cannot claim private defence as it was her own fault that she was coming home late at night.

a) I and II b) III

c) III and IV d) II.

In this case, W can claim the right of private defence.

Hence, the answer will be (a).

|

1 videos|19 docs|124 tests

|

FAQs on Indian Penal Code - Additional Study Material for CLAT

| 1. What are the elements of a crime? |  |

| 2. What kinds of punishments are there for crimes? |  |

| 3. What are general exceptions in criminal law? |  |

| 4. What is mistake of law in criminal law? |  |

| 5. How does the Indian Penal Code address mistake of law? |  |

|

Explore Courses for CLAT exam

|

|