The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 28th October, 2020 | Additional Study Material for UPSC PDF Download

1. COMPOUND CONUNDRUM-

GS 2- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors

Context

The Centre’s scheme to bear the difference between the compound interest and simple interest on retail and MSME loans availed by borrowers whose aggregate outstanding borrowings were less than ₹2 crore between March 1 and August 31, has come not a day too soon.

Identifying Beneficiaries

(i) In spelling out the norms for lenders to identify eligible beneficiaries and then ensure that the extra ‘interest on interest’ be refunded by November 5, the government has clearly been spurred by the Supreme Court’s admonition to expedite relief to small borrowers.

(ii) With the top court having pointedly referenced the approaching festival of lights when it said “the common man’s Diwali” was in the government’s hands, the Centre has ended up setting a really tight deadline of less than two weeks for banks and NBFCs to credit the differential amount to the borrowers’ accounts.

(iii) The lenders have their task cut out to make sure that they pick out all the eligible loans — education, housing, consumer durables, automobiles, consumption, credit card borrowings, as well as credit provided to MSMEs — and that the borrowings had not turned into non-performing assets as on February 29.

(iv) They will then have to refund the difference between the compound interest charged for the six-month period and the simple interest.

(v) In making all the specified borrowers eligible for the ‘ex-gratia’, the government has sought to ensure equity between those who may have availed of the repayment moratorium(temporary suspension) and others who had opted to continue to service their borrowings.

Relief And Disquet

(i) The move, however, has understandably evoked(brought) both relief and some disquiet(unease).

(ii) Retail borrowers, especially those who continued to meet their EMI commitments not with standing the disruptions caused by the pandemic and lockdowns, stand to marginally benefit from the government’s payment and will be a relieved lot.

(iii) On the other hand, MSMEs may find the assistance far too small to make a material difference, given the scale of economic hardship they have had to endure — from demand destruction, to material and labour shortages and regulatory woes.

(iv) Given that these businesses provide substantial direct and indirect employment and also generate valuable tax revenue, it would have made far greater economic sense for the government to have categorised them separately.

(v) The additional fiscal impact should be seen against the benefit that would accrue were even a reasonable number of these enterprises to remain viable and resume their contribution to the national economy.

(vi) Also, the ₹2-crore limit for retail loans provides succour to not just ‘vulnerable’ borrowers but creates a moral hazard(risk) by benefiting the well-heeled too.

(vii) All eyes will now be on the Court when it resumes hearing the matter next month.

Conclusion

While the waiver of the interest on interest is welcome, MSMEs need more help.

2. INDIA’S DISCOM STRESS IS MORE THAN THE SUM OF ITS PAST-

GS 2- Important aspects of governance, transparency and accountability

Context

(i) Distribution Companies (DisComs) have been called the lynchpin(important) but also the weakest link in the electricity chain.

(ii) For all of India’s global leadership for growth of renewable energy, or ambitions of smart energy, the buck stops with the DisComs, the utilities that typically buy power from generators and retail these to consumers.

(iii) Long gone are the days of scarcity of power; while the physical supply situation has mostly improved, the financial picture has not brightened much — and this was before COVID-19.

More Loan Than Stimulus

(i) The Indian government responded to COVID-19’s economic shock with a stimulus package of ₹20-lakh crore, out of which ₹90,000 crore was earmarked for DisComs (later upgraded to ₹1,25,000 crore).

(ii) While it was called a stimulus, it is really a loan, meant to be used by DisComs to pay off generators.

(iii) Our recent study on DisComs shows a much graver(serious) picture than one that can be solved by a fill-up, even though such a liquidity injection is required (but probably insufficient).

(iv) Newspaper reports abound with stories of how DisComs owe one lakh crore rupees to generators, and without such an infusion the chain will collapse.

(v) Unfortunately, the dues to generators are several times higher than this number, and, worse, the total short-term dues of DisComs are multiple times higher, which excludes long-term debt.

Data On Liabilities

(i) How did this magic figure of one-lakh crore capture popular imagination?

(ii) This figure is roughly what the government’s PRAAPTI (or Payment Ratification And Analysis in Power procurement for bringing Transparency in Invoicing of generators) portal shows for DisCom dues to generators.

(iii) However, what is not widely appreciated is that the portal is a voluntary compilation of dues, and is not comprehensive.

(iv) The Power Finance Corporation (PFC)’s Report on Utility Workings for 2018-19 showed dues to generators were ₹2,27,000 crore, and this is well before COVID-19.

(v) It also showed similar Other Current Liabilities.

(vi) Our analysis shows that what has happened over the years is that DisComs have delayed their payments upstream (not just to generators but others as well) — in essence, treating payables like an informal loan.

(vii) But why do DisComs not pay on time?

(viii) Conventional wisdom blames the utilities for inefficiency, including high losses, called Aggregate Technical and Commercial (AT&C) losses, a term that spans everything from theft to lack of collection from consumers.

(ix) However, this is only an incomplete explanation.

(x) To understand what is going on, we have to dig into all the accounts of DisComs.

(xi) Ideally, they should not incur losses as they enjoy a regulated rate of return.

(xii) While AT&C losses can explain part of any gap, the first problem starts at the regulatory level where even if DisComs performed as targeted, across India, they would face a non-trivial cash flow gap, which was ₹60,000-plus crore in FY18-19 compared to their then annual cost structure of ₹7.23-lakh crore.

(xiii) Then, we have the severe challenge of payables to DisComs. These dues are of three types.

(xiv) First, regulators themselves have failed to fix cost-reflective tariffs thus creating Regulatory Assets, which are effectively IOUs, which are to be recovered through future tariff hikes.

(xv) Second, about a seventh of DisCom cost structures is meant to be covered through explicit subsidies by State governments.

(xvi) Third, consumers owed DisComs over ₹1.8 lakh crore in FY 2018-19, booked as trade receivables.

States As Defaulters

(i) State governments are the biggest defaulters, responsible for an estimated a third of trade receivables, besides not paying subsidies in full or on time.

(ii) On an annual cash flow basis, the shortfall in subsidy payments appears very low — only about 1% — but cumulative unpaid subsidies, with modest carrying costs, make DisComs poorer by over ₹70,000 crore just over the last 10 years.

(iii) This earlier equilibrium of increasing the dues as well as relying on continued subsidies (not to mention extensive cross subsidies between consumer categories) all worked as long as there was steady growth.

(iv) However, such muddling along cannot suffice(enough).

(v) To begin with, COVID-19 has completely shattered incoming cash flows to utilities.

(vi) While there was a multi-month dip in demand, the revenue implications were far worse since the lockdown disproportionately impacted revenues from so-termed paying customers, commercial and industrial segments.

(vii) On the flip side, reduced demand for electricity did not save as much because a large fraction of DisCom cost structures are locked in through Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) that obligate capital cost payments, leaving only fuel savings with lower offtake.

(viii) We will probably need a much larger liquidity infusion than has been announced thus far, but it also must go hand-in-hand with credible plans to pay down growing debt.

(ix) Stimulus loans are near market term and not soft loans. If there is a haircut to be taken, all the risk and future obligations should not be placed on DisComs alone.

(x) Generators, transmission companies, and lending institutions must all chip in.

(xi) Else, we risk kicking the can down the road until we may require another future support package if not bailout.

(xii) Unfortunately, we do not have the luxury of time to put the house in order.

Renewable Energy Beckons

(i) The rise of renewable energy means that premium customers will leave the system partly first by reducing their daytime usage.

(ii) And as battery technologies mature, their dependence on DisComs may wane entirely.

(iii) Even without batteries, regulations permitting, they may want to find third party suppliers under competitive models.

(iv) So what is the solution other than simply throwing money at the problem? Improving AT&C losses is important, but will not be sufficient.

(v) We need a complete overhaul(repair) of the regulation of electricity companies and their deliverables.

(vi) Much of inefficiency is tolerated in the name of the poor but they do not get quality supply.

(vii) We need to apply common sense metrics of lifeline electricity supply instead of the political doleout of free electricity even for those who may not deserve such support.

(viii) For the rest, regulators must allow cost-covering tariffs.

(ix) The financial problems of DisComs have been brewing for many years, and it is unlikely that a silver bullet, even privatisation, can solve the problems overnight.

(xi) However, if business as usual was not even good enough before COVID-19, it will not be workable for the current national needs of quality, affordable, and sustainable power.

3. INDIA’S OUTREACH TO MYANMAR-

GS 2- India and its neighborhood- relations

Context

(i) The recent visit of Foreign Secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla and Chief of the Army Staff Gen.

(ii) Manoj Naravane to Myanmar reflected India’s multidimensional interests in the country and the deepening of ties between Delhi and Naypyidaw.

(iii) Coming a few weeks before Myanmar’s general election, the visit underscored two lines of thinking that drive India’s Myanmar policy: engagement with key political actors and balancing neighbours.

(iv) For Myanmar, the visit would be viewed as India’s support for its efforts in strengthening democratisation amidst criticisms by rights groups over the credibility of its upcoming election.

(v) The Indian delegation met State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and Myanmar’s military Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

Non-Interference In Internal Politics

(i) The political logic that has shaped India’s Myanmar policy since the 1990s has been to support democratisation driven from within the country.

(ii) This has allowed Delhi to engage with the military that played a key role in Myanmar’s political transition and is still an important political actor.

(iii) It has also enabled Delhi to work with the party in power, whether the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party that won the 2010 polls or the pro-democracy National League for Democracy, which is in power now.

(iv) India is cognisant(aware) of the geopolitical dimension of Myanmar’s democratisation.

(v) Myanmar’s political transition created challenges for Naypyidaw and limited its ties with the West.

(vi) India and a few Asian countries have engaged Myanmar keeping in mind the need to reintegrate it with the region and world.

(vii) This has been a strategic imperative(needful) for Naypyidaw as part of its policy of diversifying its foreign engagements.

(viii) A key factor behind the military regime’s decision to open the country when it initiated reforms was, in part, to reduce dependence on China.

(ix) By engaging Myanmar, Delhi provides alternative options to Naypyidaw.

(x) This driver in India’s Myanmar policy has perhaps gained greater salience in the rapidly changing regional geopolitics.

Recent Initiatives

(i) Like in other neighbouring countries, India suffers from an image of being unable get its act together in making its presence felt on the ground.

(ii) Some initiatives announced during the joint visit suggest Delhi is taking steps to leverage its political, diplomatic, and security ties with Myanmar to address some of these issues.

(iii) The inauguration of the liaison(contact) office of the Embassy of India in Naypyidaw may seem a routine diplomatic activity.

(iv) However, establishing a permanent presence in the capital where only a few countries have set up such offices does matter.

(v) Interestingly, China was the first country to establish a liaison office in Naypyidaw in 2017.

(vi) India has also proposed to build a petroleum refinery in Myanmar that would involve an investment of $6 billion is another indication of Myanmar’s growing significance in India’s strategic calculus, particularly in energy security.

(vii) It also shows India’s evolving competitive dynamic with China in the sector at a time when tensions between the two have intensified.

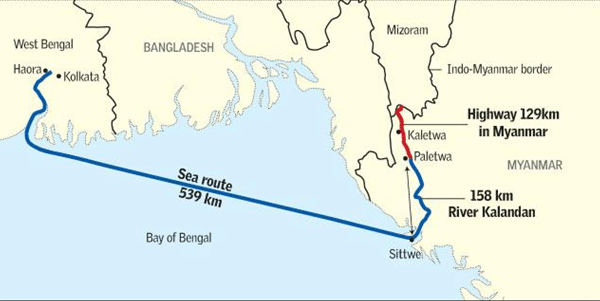

(viii) Another area of cooperation that has expanded involves the border areas.

(ix) The joint visit reiterated the “mutual commitment not to allow respective territories to be used for activities inimical(enemy) to each other.”

(x) Both Delhi and Naypyidaw have been collaborating in the development of border areas with the understanding that it is the best guarantee to secure their borders.

(xi) And this is an area where the fruits of bilateral cooperation are already evident on the ground.

Conclusion

(i) Last, for Delhi, the balancing act between Bangladesh and Myanmar remains one of the keys to its overall approach to the Rohingya issue.

(ii) Delhi has reiterated its support for “ensuring safe, sustainable and speedy return of displaced persons” to Myanmar.

(iii) The choices before Delhi are limited on the issue.

(iv) By positioning as playing an active role in facilitating the return of Rohingya refugees to Myanmar, India has made it clear that it supports Myanmar’s efforts and also understands Bangladesh’s burden.

(v) For Delhi, engaging rather than criticising is the most practical approach to finding a solution.

(vi) Delhi’s political engagement and diplomatic balancing seems to have worked so far in its ties with Myanmar.

(vii) Whether it has leveraged these advantages on the ground to the full is open to debate.

(viii) The aforementioned initiatives could be the beginning of change on the ground by establishing India’s presence in sectors where it ought to be more pronounced.

(ix) For India, Myanmar is key in linking South Asia to Southeast Asia and the eastern periphery becomes the focal point for New Delhi’s regional outreach.

|

21 videos|562 docs|160 tests

|

FAQs on The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 28th October, 2020 - Additional Study Material for UPSC

| 1. What is the significance of the Hindu Editorial Analysis for the UPSC exam? |  |

| 2. How can the Hindu Editorial Analysis help in UPSC preparation? |  |

| 3. Can the Hindu Editorial Analysis be used as a source for essay writing in the UPSC exam? |  |

| 4. How frequently is the Hindu Editorial Analysis updated? |  |

| 5. Can the Hindu Editorial Analysis be accessed offline for UPSC preparation? |  |