Notes: Nationalist Movement | Social Studies & Pedagogy Paper 2 for CTET & TET Exams - CTET & State TET PDF Download

Introduction

- The groundwork for the nationalist movement was laid in the 19th century India.

- Various factors contributed to this foundation, including socio-religious reform movements, the spread of modern Western education, the emergence of a middle class, and the economic impact of British rule.

- These factors generated political awareness and gave rise to the concept of 'nationhood' and nationalist aspirations.

- The Indian National Congress was founded in 1885, marking the beginning of the organized nationalist movement.

Rise of Nationalism

Nationalism during the British period in India can be understood through various developments:

- British control over India's resources and people was absolute, creating a sense of resentment and the need for self-governance.

- Political associations formed in the late 19th century, such as the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, Indian Associations, Madras Mahajan Sabha, Bombay Presidency Association, and the Indian National Congress, played a crucial role in uniting Indians against British rule.

- The Arms Act of 1878 and the Vernacular Press Act aimed to suppress Indian voices and disarm the population, further fueling discontent.

- The Ilbert Bill controversy in 1883, which sought to equalize the judicial system for Indians and Europeans, highlighted the racial inequalities and stirred public opinion.

- The Indian National Congress was established in 1885 with the help of figures like A.O. Hume, marking the beginning of organized political action against British rule.

Lord Macaulay's Education Policy, 1835

Lord Macaulay's education policy in 1835 aimed to promote English education in India, focusing on the upper strata of society. Key aspects of the policy included:

- Abolishing Persian as the court language and replacing it with English.

- Allowing the free printing of English books, making them accessible at lower prices.

- Establishing institutions such as the Bethune School in Calcutta (1849), Agriculture Institute at Pusa (Bihar), and Engineering Institute at Roorkee to promote education and professional training.

A Nation in Making

After the formation of the Indian National Congress (INC), India was on the path of nation-building. The early years of the INC were characterized by:

- A moderate approach, focusing on demanding a greater role for Indians in governance and administration.

- Advocating for more representative and powerful legislative councils and the inclusion of Indians in high government positions.

- Promoting the idea of conducting Civil Service examinations in India, not just in London.

- In contrast, leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and Lala Lajpat Rai in Bengal, Maharashtra, and Punjab were pushing for more radical approaches.

- They criticized the moderates for their 'Politics of Prayers' and emphasized self-reliance and the need to fight for self-rule (Swaraj).

- Bal Gangadhar Tilak popularized the slogan "Freedom is my birthright and I shall have it!" reflecting the growing demand for immediate self-governance.

The partition of Bengal in 1905 by Viceroy Curzon, under the pretext of administrative convenience, was a significant event that spurred nationalist sentiments.

Surat Split, 1907

During the Swadeshi movement, the differences between the moderates and the extremists within the Indian National Congress became more pronounced. These differences were rooted in several issues, including:

- Spread of the Boycott Movement: The extremists wanted to extend the Boycott and Swadeshi movements beyond Bengal. They aimed to include government services, law courts, the Legislative Council, and all forms of associations with the British in their programme. In contrast, the moderates were not in favor of this expansion.

- Methods of Struggle: There was a conflict over the methods to be used in the struggle against the British. The extremists had a more radical approach, while the moderates preferred a milder strategy.

- Ideological Differences: The moderates and extremists had different ideologies regarding the approach to achieving independence.

- Personality Clashes: Personalities and leadership styles also contributed to the widening rift between the two factions.

The growing differences between the moderates and the extremists became evident at the Surat Session of the Congress in 1907.

- Outcome of the Surat Session: At this session, the moderates, who were in the majority, gained complete control over the Congress organisation. As a result, the extremists were suspended from the Indian National Congress.

Lucknow Pact, 1916

The Lucknow Session of 1916 was significant for two major developments:

(i) The readmission of the extremists into the Congress.

(ii) The formation of an alliance between the Congress and the Muslim League.

The Muslim League, during its Annual Session in 1915 in Bombay, which was also attended by several Congress leaders like Gandhi, Malaviya, and Sarojini Naidu, laid the groundwork for this agreement. This pact is commonly referred to as the Lucknow Pact or the Congress-League Scheme and was largely the result of Tilak’s efforts.

The Lucknow Pact called upon the British Government to grant self-government to India as soon as possible. It also demanded that the authority to make appointments to the Indian Civil Services, as well as the military and naval services, should rest with the Government of India. Additionally, the pact marked the formal acceptance of separate electorates for Muslims.

The pact played a role in the implementation of the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919. The Congress-League alliance, or the Lucknow Pact, lasted until 1922, following the Chauri-Chaura incident. However, the fundamental flaw of the Lucknow Pact was its assumption that Hindus and Muslims constituted separate communities, which ultimately made the agreement a temporary arrangement.

Home Rule Movement, 1916

Background

- The Home Rule Movement emerged as a response to the prevailing conditions during World War I and marked the beginning of a new phase of assertive politics in India. Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak were at the forefront of this movement, leading the charge for greater self-governance within the British Empire.

- The campaign for Home Rule gained momentum with the launch of the weekly publication The Commonweal on January 2, 1914. This was followed by Tilak establishing the Indian Home Rule League in April 1916. Later, in September 1916, Annie Besant initiated her own Home Rule League.

Objectives and Scope

- The primary goal of the Home Rule League was to achieve self-governance for India within the framework of the British Empire, similar to the autonomous colonies of Australia and New Zealand.

Leadership and Organization

- Tilak’s League focused on regions including Maharashtra (excluding Bombay City), Karnataka, the Central Province, and Berar.

- Annie Besant’s League was responsible for the rest of India.

The August Declaration or Montague Declaration, 1917

- Background: After World War I, there was a surge in revolutionary activities and the Home Rule movement gained popularity in India. This put pressure on the British to change their policies and adopt a more conciliatory approach towards Indian nationalists.

- Montague's Declaration: On August 20, 1917, Montague, the Secretary of State for India, made a significant declaration in the House of Commons outlining the goals of British policy in India. This declaration aimed to address the growing demands for political reform in India.

- Montague's Visit to India: Following the declaration, Montague visited India in November 1917 to gather opinions from various political groups in the country. His aim was to understand the diverse perspectives on constitutional reforms.

- Report on Indian Constitutional Reforms: Based on Montague's discussions during his visit to India, a detailed report on Indian constitutional reforms was prepared. This report was published in July 1918 and laid the groundwork for future reforms.

- Government of India Act, 1919: The report prepared after Montague's visit became the basis for the Montague-Chelmsford reforms, which were implemented through the Government of India Act in 1919. This act marked a significant step towards constitutional reforms in India.

The Rowlatt Act, 1919

The Rowlatt Act was enacted in 1919 and can be understood as follows:

- In 1917, Governor-General Chelmsford appointed a committee chaired by Justice Sydney Rowlatt to investigate revolutionary activities and recommend necessary legislation to address them. This committee became known as the Sedition or Rowlatt Committee.

- The Rowlatt Act proposed the trial of offenses by a special court comprising three High Court judges. There was no right to appeal against the decisions of this court, and it could consider evidence that was not admissible under the Indian Evidence Act.

- The Act granted the government the authority to search premises and arrest individuals without a warrant.

- It also allowed for detention without trial for a maximum period of two years.

Anti-Rowlatt Satyagraha

Gandhiji's Opposition to the Rowlatt Act

- Formation of Satyagraha Sabha: On February 24, 1919, in Bombay, Gandhiji formed the Satyagraha Sabha to launch his campaign against the Rowlatt Bill.

- Initial Condemnation: Gandhiji's decision to start Satyagraha was criticized by several liberals, including Sir DE Wacha, Surendranath Bannerjee, TB Sapru, Srinivas Shastri, and Annie Besant.

- Call for Hartal: The date for the hartal (strike) was set for April 6, 1919. However, in Delhi, the hartal was observed earlier on March 30, leading to police firing that resulted in the deaths of ten people.

- Arrests and Violence in Amritsar: On April 10, 1919, the arrest of Dr. Kitchlew and Dr. Satyapal in Amritsar triggered mob violence. Government buildings were set on fire, five Englishmen were killed, and a woman was assaulted.

Khilafat Movement, 1919

The Khilafat Movement was supported by the Congress, and it is discussed below in brief.

- The Sultan of Turkey, who ruled over the vast Ottoman Empire, was the Caliph of the Islamic world. Indian Muslims regarded him as their spiritual leader, the Khalifa.

- During World War I, Turkey was defeated, and the harsh terms of the Treaty of Sevres in 1920 further inflamed tensions.

- Additionally, revolts in Arab lands against the Sultans, instigated by the British, heightened Muslim sentiments in India. As a result, Muslims began the Khilafat Movement.

Swaraj Party

The Swaraj Party was formed in December 1922 after a split in the Indian National Congress during the Gaya Session.

Background

- At the Gaya Session of the Congress, there was a heated debate between two factions:

- The 'pro-changers' who supported entering the legislative councils to fight for reforms.

- The 'no-changers' led by Rajagopalachari, who opposed this strategy.

Formation of the Swaraj Party

- The 'no-changers' faction won the debate, leading to the resignation of CR Das and Motilal Nehru from their positions in the Congress.

- In response, CR Das, Motilal Nehru, and other supporters of council entry formed the Congress-Khilafat Swaraj Party, commonly known as the Swaraj Party, on December 31, 1922.

- CR Das became the President of the Swaraj Party, and Motilal Nehru its Secretary.

Simon Commission

The Simon Commission was established to recommend reforms and is discussed below.

- On November 8, 1927, Lord Birkenhead, the Secretary of State for India, announced the formation of a Statutory Commission chaired by Sir John Simon. This commission was officially called the Indian Statutory Commission. All seven members of the commission were Englishmen from the British Parliament.

- The purpose of the commission was to assess the implementation of the 1919 reforms and propose further changes.

- The Simon Commission, lacking Indian representation, faced strong opposition. The Congress Party, during its session in Madras in December 1927, decided to boycott the commission.

- However, other groups such as the Muslim League led by Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the Justice Party in Madras, the Unionist Party in Punjab, the Central Sikh Sangh, and the All India Achhut Federation did not oppose the commission.

- The proposals put forth by the Simon Commission were entirely rejected by major political parties in India, including the Muslim League.

Butler Committee, 1927

The Butler Committee, formed in 1927, aimed to investigate and propose solutions for the relationship between Indian princely states and the British government, particularly focusing on economic relations.

Background

- In 1927, the people of princely states organized the State People's Conference to advocate for self-government institutions.

- This movement alarmed the princes, prompting them to seek British assistance.

Formation of the Committee

- In response, the British set up a three-member committee consisting of Harcourt Butler, W.S. Holdsworth, and S.C. Peel, with Harcourt Butler as the Chairman.

Objectives

- The committee was tasked with examining the relationship between Indian states and the paramount power (the British) and suggesting ways to improve economic relations between British India and the princely states.

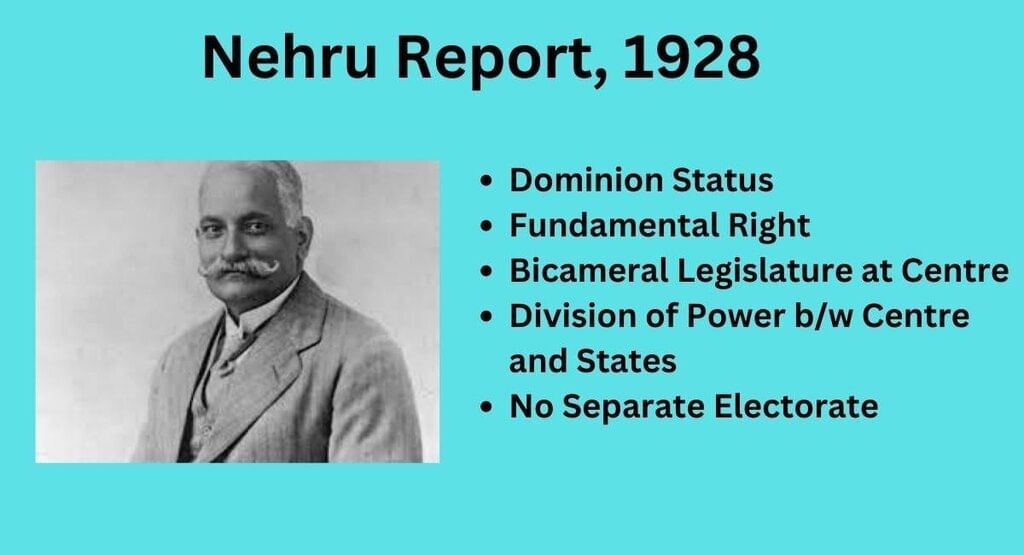

Nehru Report

The Simon Commission was appointed in 1928 to review the Government of India Act 1919 and propose reforms. However, the Commission faced widespread criticism because it had no Indian members.

- In response to this and the challenge posed by Lord Birkenhead, the Secretary of State for India, the All Parties Conference was convened in Delhi on February 12, 1928. The conference aimed to unite various political factions in India to formulate a response to the Simon Commission.

- The conference was presided over by M. A. Ansari and later, on May 19, 1928, during a meeting in Bombay, the All Parties Conference appointed a committee to draft the principles for a new Constitution for India, with Motilal Nehru as its chairman.

The committee included several prominent figures:

- Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru: A respected lawyer and political figure known for his moderate views.

- Sir Ali Imam: A politician and member of the Indian National Congress.

- M. S. Aney: A legal expert and politician.

- Mangal Singh: A lesser-known figure in the political landscape.

- Shoaib Qureshi: A politician and member of the All India Muslim League.

- G. R. Pradhan: A political figure involved in the Congress party.

- N. M. Joshi: A trade union leader and politician.

- M. R. Jayakar: A lawyer and politician known for his advocacy of Hindu-Muslim unity.

- Subhash Chandra Bose: A prominent nationalist leader who later became a key figure in the Indian independence movement.

The committee's task was to outline the fundamental principles that should guide the constitution for India, setting the stage for future discussions and developments in Indian constitutional law.

Lahore Session of the Congress, 1929

In 1929, the Annual Session of the Indian National Congress took place in Lahore, with Jawaharlal Nehru serving as the President. This session was significant in shaping the future of the Indian independence movement.

During the Lahore Session, several important resolutions were passed:

- Rejection of Dominion Status: The Nehru Committee's recommendation for dominion status was no longer acceptable.

- Poorna Swaraj Resolution: The term "Swaraj" in the Congress Constitution was redefined to mean complete independence.

- Boycott of Round Table Conference: The upcoming Round Table Conference in London was to be boycotted.

- Launch of Civil Disobedience: A Programme of Civil Disobedience was to be initiated, with Mahatma Gandhi planning to violate the salt laws at Dandi.

On December 31, 1929, Jawaharlal Nehru unfurled the flag of India's independence on the banks of the Ravi River in Lahore. The Congress Working Committee also declared January 26, 1930, as Poorna Swaraj Day (Independence Day).

Dandi March (Salt Satyagraha)

The Dandi March, also known as the Salt Satyagraha, was a pivotal event in the Indian independence movement.

Beginning of the March

- On 12th March 1930, Mahatma Gandhi commenced the historic march from his Sabarmati Ashram, accompanied by 78 followers.

Breaking the Salt Law

- After a 24-day journey, Gandhi symbolically broke the Salt law at Dandi on 5th April 1930.

- This act formally inaugurated the Civil Disobedience Movement.

Nationwide Defiance

- Following Gandhi's lead, defiance of the Salt law spread across the country.

- In Tamil Nadu, C. Rajagopalachari led a salt march from Trichinopoly to Vedaranniyam on the Tanjore coast.

- In Malabar, K. Kelappan, a prominent figure in the Vaikom Satyagraha, walked from Calicut to Payyanur to break the Salt law.

First Round Table Conference

The First Round Table Conference was convened following a recommendation by Sir John Simon to the British Government. He suggested bringing together representatives from both British India and the Indian states to make a final decision on constitutional reforms for India. Lord Irwin's declaration led to the calling of this conference.

The First Session of the Round Table Conference started on 12th November 1930. The delegation from British India included 58 members, while the rest were British officials. Some prominent participants in the conference included:

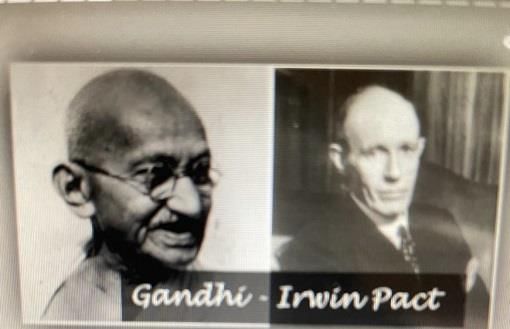

Gandhi-Irwin Pact, 1931

The Gandhi-Irwin Pact, reached on March 5, 1931, was a significant agreement during the Civil Disobedience movement in India. Here’s a detailed overview of the events leading to the pact and its key points:

Background:

- The Simon Commission report was published during the Civil Disobedience movement, prompting the need for discussion and consideration of its recommendations.

- In response, the First Round Table Conference was convened in London in November 1930 to discuss constitutional reforms.

Initiation of Talks:

- On February 14, 1931, Mahatma Gandhi initiated talks with Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of India, to discuss the ongoing Civil Disobedience movement and the future of constitutional reforms.

- These discussions eventually led to the Delhi Pact on March 5, 1931, commonly known as the Gandhi-Irwin Pact.

Key Agreements:

- The Indian National Congress, represented by Gandhi, agreed to participate in the Second Round Table Conference to discuss constitutional reforms based on key principles:

- Federation: A federal structure for governance.

- Responsibility: A system of responsible government.

- Safeguards: Safeguards for essential matters such as defense, external affairs, minorities, and the financial credit of India.

Discontinuation of Civil Disobedience:

- Gandhi agreed to discontinue the Civil Disobedience Movement on behalf of the Congress as part of the pact.

Government Concessions:

- The government agreed to release all political prisoners, except those convicted of violence, and to restore the confiscated property of satyagrahis (participants in nonviolent civil disobedience).

Rejection of Death Sentence Remittance:

- Gandhi’s request to remit the death sentences of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru was denied by the Viceroy, highlighting the ongoing tensions and challenges in the negotiation process.

The Gandhi-Irwin Pact was a crucial step in the broader struggle for Indian independence, setting the stage for further negotiations and discussions on constitutional reforms.

Second Round Table Conference

In April 1931, Wellington took over from Lord Irwin as the Viceroy in Delhi. Sir Samuel Hoare, a prominent conservative figure, became the Secretary of State for India.

The Congress Party had paused its Civil Disobedience movement but continued to emphasize Poorna Swaraj (complete self-rule) as its ultimate political objective.

Poona Pact, 1932

The Poona Pact was an agreement between B.R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi, signed on September 25, 1932.

According to this pact, Ambedkar agreed to withdraw his demand for a separate electorate for Harijans (Dalits). Instead, the principle of a common electoral system was adopted.

Third Round Table Conference

The Third Round Table Conference was held on November 17, 1932. The Indian National Congress decided to boycott this conference. Notable participants included T. B. Sapru and B. R. Ambedkar.

Following discussions at the three Round Table Conferences, the British Government drafted proposals for reforming the Indian Constitution. These proposals were published in a white paper in March 1933.

The white paper was reviewed and approved by a Joint Committee of the British Parliament in October 1934. Subsequently, a bill based on the committee's report was introduced and passed in the British Parliament, leading to the Government of India Act 1935.

Revolutionary Activities

The revolutionary activities against the British were carried out in two phases which are as follows.

First Phase

Vasudev Balwant Phadke, known as the Father of Militant Nationalism, gathered backward classes, including Kols and Bhils, to incite rebellion within the British Empire. However, he was captured and deported to Aden. By 1902, four revolutionary groups were established in Calcutta and Midnapur.

- Midnapur Society founded by Sarla Ghosal.

- Anushilan Samiti.

- Atmonnoti Group.

- Yugantar Group founded by Barindra Kumar Ghosh, Raja Subodh Malik, and Hemchandra Qanungo.

Key Events:

- 1906: The first political robbery, known as the Rangpur Dacoity, was conducted.

- Bomb Manufacturing: A bomb manufacturing unit was established at Maniktala in Calcutta.

- Arrests: Aurobindo Ghosh was arrested, and Khudiram Bose was arrested and executed in Hijni jail, Hazaribagh.

- Assassination Attempt: An attempt was made on the life of Governor-General Lord Hardinge in December 1912 by Master Amir Chandra, Awadh Bihari, and Basant Kumar Biswas.

Prominent Groups:

- India House: Founded by Shyamji Krishna Verma in London, it aimed to promote Indian nationalism. Verma also started the newspaper The Indian Sociologist, where V.D. Savarkar was a member. Savarkar later founded secret societies like Abhinav Bharat and Mitra Mela.

- Paris Indian Society: Founded by Madam Bhikaji Cama, who started two newspapers, Vande Mataram and Madan Talwar, to promote Indian nationalism.

- India Independence Committee: Established by Virendranath Chattopadhyay in Berlin to advocate for Indian independence.

- Ghadar Party Movement: Initiated by Indian nationalists, including students like Tarak Nath Das in North America, to raise awareness about nationalism through publications like Free Hindustan newspaper.

Second Phase

1925: Kakori Train Dacoity Case

- Ram Prasad Bismil and Ashfaqullah Khan were accused in the Kakori train dacoity case.

1929: Murder of Saunders and Assembly Bomb Case

- Bhagat Singh was accused in the murder of J.A. Saunders, Assistant Superintendent of Police in Lahore.

- In the Assembly Bomb Case in Delhi, Bhagat Singh, Batukeshwar Dutta, and Rajguru were involved.

1930: Chittagong Armoury Dacoity

- Surya Sen was accused in the Chittagong Armoury Dacoity.

1940: Murder of General Dyer

- Udham Singh murdered General Dyer in London in 1940.

Congress Ministries in Office (1937-1939)

The Congress party was in power in eight provinces for a total of 28 months. During this time, they focused on improving conditions for Indians.

- Protection for Peasants: In all provinces governed by Congress, efforts were made to protect peasants from moneylenders and to enhance irrigation facilities.

- Tenancy Bills: In the United Provinces and Bihar, Tenancy Bills were passed to safeguard tenant rights.

- Textile Enquiry Committee: In 1937, the Congress Government in Bombay set up a Textile Enquiry Committee that recommended better wages, health, and insurance coverage for workers.

Other Major Achievements:

- Reduction in the salaries of ministers.

- Declaration of Fundamental Rights.

- Implementation of welfare schemes for tribal communities.

- Reforms in jails.

- Conducting commercial and economic surveys and promoting village industries.

- Enhancing education, particularly primary education, through the introduction of basic education.

National Planning Committee: The Congress Government also participated in planning efforts through the National Planning Committee established in 1938 by Congress President Subhash Chandra Bose.

The August Offer, 1940

On August 8, 1940, Viceroy Lord Linlithgow made a statement from Simla known as the August Offer. The main aim of this proposal was to gain the cooperation of the Congress Party during World War II.

- The offer rejected the Congress demand for establishing a provincial National Government but promised the following:

- Immediate expansion of the Viceroy’s Executive Council by increasing the number of Indian members.

- Formation of a representative Constitution-making body after the war.

- Establishment of a War Advisory Council with representatives from British India and the Indian states.

- Granting dominion status in the unspecified future.

- Allowing the right to secede for certain provinces.

The Individual Satyagraha

Within the Indian National Congress (INC), there were differing views on whether to launch a campaign of Civil Disobedience against British rule. Mahatma Gandhi believed that the conditions were not ripe for such a movement due to existing divisions and indiscipline within the Congress. In contrast, some Congress leaders, socialists, and the All India Kisan Sabha were eager to initiate a struggle immediately.

- The August Offer of 1940 had left the Congress feeling disillusioned. In September 1940, Gandhi held a lengthy meeting with the Viceroy at Simla to discuss the situation.

- On October 17, 1940, Acharya Vinoba Bhave, chosen by Gandhi, became the first Satyagrahi by delivering an anti-war speech at Paunar, marking the start of the Individual Satyagraha.

- However, Gandhi suspended the movement on December 17, 1940, due to the lack of enthusiasm it generated. Jawaharlal Nehru was the second to offer Satyagraha after Vinoba Bhave, and it was during this movement that Gandhi publicly declared Nehru as his successor. The Individual Satyagraha was also referred to as the Delhi Chalo Satyagraha.

Cripps Mission, 1942

As the situation in World War II deteriorated, particularly after Germany invaded Russia, pressure mounted on British Prime Minister Winston Churchill from various quarters, including U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, and the Labour Party in Britain, to seek the active cooperation of Indians in the war effort. In response,

- Churchill sent a mission led by Sir Stafford Cripps, a member of the British War Cabinet and a left-wing Labourite, to India. The aim was to resume dialogue with the Congress and other political parties to garner their support for the British war efforts.

- However, the Cripps proposal faced significant objections. The Congress Working Committee criticized the composition of the proposed Constitution-making body, where representatives from the princely states would be nominated by their rulers rather than elected by the people.

- The Congress was unwilling to rely on future promises and demanded a responsible government with full powers, including control over the country’s defense. Gandhi described the provision regarding the non-accession of provinces to the union as "an invitation to the Muslim League to create Pakistan," and overall, he deemed the proposal a "post-dated cheque on a crashing bank."

- The Muslim League also rejected the Cripps offer, demanding a clear declaration from the British for a separate state for Muslims and a 50:50 seat allocation in the Interim Government. The League's rejection was based on two main grounds: the failure to recognize separate electorates for the Constitution-making body and the lack of a clear acceptance of the demand for partition.

Quit India Movement (QIM) or August Revolution, 1942

- Background: In 1942, during World War II, the Japanese forces were advancing towards India’s Eastern frontier. In response to this threat, the Congress Working Committee, led by Mahatma Gandhi, believed that the presence of the British in India was actually inviting Japanese invasion. Gandhi argued that if the British withdrew, it would remove this invitation.

- Quit India Resolution: On July 14, 1942, the Congress Working Committee met in Wardha and passed the Quit India Resolution, calling for the British to leave India. Gandhi famously urged the British to leave India “in God’s hands.”

- Do or Die: During the Quit India Movement, Gandhi issued the rallying cry of “Do or Die,” urging Indians to take decisive action for independence. The historic meeting where this slogan was popularized took place in August 1942 at Gowalia Tank in Bombay, which is now known as August Kranti Maidan.

Rajagopalachari Formula, 1944

C. Rajagopalachari, who had left the Congress party in 1943, recognized the importance of reaching a settlement between the Congress and the Muslim League for India's independence. In 1944, he proposed a formula to facilitate talks with Jinnah.

The key points of this formula included:

- The Muslim League should endorse the Indian demand for independence and cooperate with the Congress in forming a Provincial Interim Government for the transitional period.

- After the war, a commission would be appointed to delineate contiguous districts in the North-West and North-East with an absolute Muslim majority.

- A plebiscite would be held for the inhabitants of these districts to decide on the question of a separate state, based on adult suffrage.

- All parties would be allowed to advocate their views before the plebiscite.

- In the event of separation, essential common services like defense, commerce, and communication would be jointly managed.

- Any transfer of population would be strictly on a voluntary basis.

- The scheme would be implemented only after the full transfer of power by the British.

Jinnah rejected Rajagopalachari's proposal, calling it a 'Mutilated and North-Eastern Pakistan.' However, he agreed to engage in talks with Gandhi. Jinnah insisted that only Muslims should vote on the partition, while Gandhi refused this notion as it was based on the Two-Nation theory.

Wavell Plan, 1945

- Political Deadlock: Since the resignation of Congress Ministries in 1939, India faced a political deadlock. To address this impasse, Viceroy Lord Wavell traveled to England for consultation in March 1945.

- Release of Congress Leaders: To create a conducive atmosphere for dialogue, Wavell ordered the release of all Congress Working Committee members on June 14, 1945. On the same day, he announced the Wavell Plan.

- Proposed Executive Council: The Wavell Plan suggested the formation of a new Executive Council at the center, with all members being Indian except for the Viceroy and Commander-in-Chief.

- Representation of Muslims: The proposed Executive Council was to have 14 members. Notably, Muslims, who constituted about 25% of India’s population, were given the right to be overrepresented by selecting six representatives.

Cabinet Mission Plan, 1946

- Background: 22nd January 1946: Decision to send the Cabinet Mission to India. 19th February 1946: British Prime Minister C.R. Attlee announced the mission and the plan to quit India in the House of Lords.

- Cabinet Mission: A high-powered mission consisting of three British Cabinet members: Sir Patrick Lawrence: Secretary of State for India Sir Stafford Cripps: President of the Board of Trade A.V. Alexander: First Lord of the Admiralty The mission arrived in Delhi on 24th March 1946.

- Objectives: 1. Peaceful Transfer of Power: To explore ways for a peaceful transfer of power in India. 2. Constitution-Making Machinery: To suggest measures for the formation of a Constitution-making body. 3. Interim Government: To discuss the establishment of an Interim Government.

Constituent Assembly

- In July 1946, elections were held for the Constituent Assembly of India. Out of 292 seats allocated to British India, the Indian National Congress won 201 seats, the Muslim League secured 73, independents got 8, and members from other parties accounted for 6 seats. Four seats were left vacant due to the Sikh community's refusal to participate.

- The Constituent Assembly convened for the first time on December 9, 1946, in the library of the Council Chamber in Delhi, with 205 members present. Representatives from the Muslim League and nominees from princely states did not attend. On December 11, the Assembly elected Dr. Rajendra Prasad as its permanent President.

The Mountbatten Plan of 1947

- On February 20, 1947, British Prime Minister Attlee announced in the House of Commons that Britain would withdraw from India by June 30, 1948. This announcement, known as Attlee’s Declaration, aimed to pressure Indians into settling their differences before the fixed withdrawal date.

- Lord Mountbatten, the last British Governor-General and Viceroy, arrived in India on March 22, 1947. He believed that partition was the only viable solution. After the Congress Party reluctantly agreed to the idea of partition, Mountbatten held final discussions with Congress, the Muslim League, and Sikh leaders to gain their consensus on the partition plan. He then visited London for further consultations in May 1947.

- The Mountbatten Plan proposed the division of India while aiming to maintain maximum unity, with the creation of Pakistan kept as small as possible. It stipulated that power would be transferred to India and Pakistan by August 15, 1947, on the basis of dominion status. The plan outlined the procedure for this transfer of power.

|

75 videos|311 docs|77 tests

|

FAQs on Notes: Nationalist Movement - Social Studies & Pedagogy Paper 2 for CTET & TET Exams - CTET & State TET

| 1. What were the main goals of the Home Rule Movement in 1916? |  |

| 2. What was the significance of the August Declaration of 1917? |  |

| 3. What were the main provisions of the Rowlatt Act of 1919? |  |

| 4. What was the purpose of the Khilafat Movement in 1919? |  |

| 5. What were the objectives of the Swaraj Party established in 1923? |  |