Passage Based Questions on Family Law | Legal Reasoning for CLAT PDF Download

Passage 1: Hindu Marriage and Divorce

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA), governs marriage and divorce among Hindus, defining marriage as a sacramental union under Section 5, which requires conditions like monogamy and mental capacity. Section 13 provides grounds for divorce, including cruelty, desertion, and adultery, with cruelty encompassing both physical and mental harm, as clarified in Dastane v. Dastane (1975). The 2005 amendment introduced irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground via mutual consent under Section 13B, reflecting modern societal shifts. In Naveen Kohli v. Neelu Kohli (2006), the Supreme Court recommended recognizing irretrievable breakdown even without mutual consent, though not yet legislated. Maintenance under Section 24 (pendente lite) and Section 25 (permanent alimony) ensures financial support, guided by principles of fairness, as seen in Vinita Saxena v. Pankaj Pandit (2006). Consider a scenario: Arjun and Priya, married under the HMA in 2018, faced marital discord by 2023. Priya alleged Arjun’s constant verbal abuse and refusal to cohabit constituted cruelty, filing for divorce under Section 13(1)(ia). Arjun countered that Priya deserted him for two years without cause, seeking dismissal of her petition. Priya also sought interim maintenance under Section 24, citing her unemployment, while Arjun, a software engineer, argued she was qualified to earn. The court must assess whether Arjun’s behavior amounts to cruelty per Suman Kapur v. Sudhir Kapur (2009), which expanded mental cruelty to include emotional distress. Desertion requires intent to abandon, as per Bipin Chander v. Prabhawati (1957). In 2025, Indian courts increasingly interpret cruelty broadly, reflecting evolving gender dynamics, yet face challenges balancing sacramental values with individual autonomy. If Priya proves cruelty, she may secure divorce and maintenance, but Arjun’s desertion claim could complicate liability. The case also raises questions about maintenance quantum, as courts consider lifestyle and earning capacity, per Shalija v. Khobanna (2018). The ongoing debate over a Uniform Civil Code (UCC), as referenced in Sarla Mudgal v. Union of India (1995), underscores tensions between personal laws and secular reforms, particularly in divorce proceedings. 1. What is a key condition for a valid Hindu marriage under Section 5 of the HMA?

1. What is a key condition for a valid Hindu marriage under Section 5 of the HMA?

(A) Mutual consent for divorce

(B) Monogamy of both parties

(C) Financial independence

(D) Registration of marriage

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage states that Section 5 of the HMA requires conditions like monogamy for a valid Hindu marriage. Option (A) is incorrect, as mutual consent applies to divorce under Section 13B, not marriage validity. Option (C) is wrong, as financial independence is not a statutory requirement. Option (D) is incorrect, as registration, while encouraged, is not mandatory for validity.

2. In the scenario, what ground might Priya use to seek divorce from Arjun?

(A) Desertion

(B) Cruelty

(C) Adultery

(D) Mutual consent

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage notes that Priya alleges Arjun’s verbal abuse and refusal to cohabit as cruelty under Section 13(1)(ia). Option (A) is incorrect, as desertion is Arjun’s counterclaim, not Priya’s ground. Option (C) is wrong, as no adultery is alleged. Option (D) is incorrect, as mutual consent under Section 13B is not claimed.

3. Which case expanded the definition of mental cruelty in Hindu divorce law?

(A) Dastane v. Dastane

(B) Suman Kapur v. Sudhir Kapur

(C) Naveen Kohli v. Neelu Kohli

(D) Sarla Mudgal v. Union of India

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage cites Suman Kapur v. Sudhir Kapur (2009) as expanding mental cruelty to include emotional distress. Option (A) is incorrect, as Dastane (1975) established cruelty but did not focus on mental aspects. Option (C) is wrong, as Naveen Kohli addressed irretrievable breakdown. Option (D) is irrelevant, as Sarla Mudgal concerns bigamy and UCC.

4. If Priya proves cruelty, what additional remedy might she secure besides divorce?

(A) Annulment of the marriage

(B) Interim maintenance under Section 24

(C) Restitution of conjugal rights

(D) Extension of divorce proceedings

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage indicates Priya seeks interim maintenance under Section 24 due to her unemployment, a remedy available if cruelty is proven. Option (A) is incorrect, as annulment applies to voidable marriages under Section 12, not divorce. Option (C) is wrong, as restitution is not sought. Option (D) is incorrect, as maintenance does not extend proceedings.

5. What broader issue does the scenario highlight in Hindu family law?

(A) Balancing sacramental values with individual autonomy

(B) Enforcing international treaties

(C) Protecting intellectual property rights

(D) Regulating corporate governance

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: A

The passage highlights the tension between the HMA’s sacramental view of marriage and modern autonomy in divorce, as seen in Priya’s case. Option (B) is irrelevant, as treaties are not discussed. Option (C) is wrong, as IPR is unrelated. Option (D) is incorrect, as corporate governance is not a family law issue.

Passage 2: Muslim Personal Law and Maintenance

Muslim personal law in India, derived from Sharia and codified in parts by statutes like the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986 (MWPDA), governs marriage, divorce, and maintenance. Under Muslim law, marriage (nikah) is a civil contract requiring offer, acceptance, and mehr (dower), as per Abdul Kadir v. Salima (1886). Divorce can be initiated via talaq (by husband), khula (by wife with consent), or judicial dissolution under the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939, for grounds like cruelty or non-maintenance. Maintenance during iddat (post-divorce waiting period) and beyond was contentious until Shayara Bano v. Union of India (2017), which declared instant triple talaq unconstitutional. The MWPDA limits maintenance to iddat unless extended under Section 125 of the CrPC, as clarified in Danial Latifi v. Union of India (2001). Consider a scenario: Ayesha married Zaid in 2019 under Muslim law. In 2024, Zaid pronounced triple talaq, claiming it ended the marriage, and refused maintenance, arguing his obligation ended post-iddat. Ayesha approached the court, seeking maintenance under Section 125 CrPC and challenging the talaq’s validity per Shayara Bano. She argued Zaid’s failure to provide for two years constituted cruelty, warranting judicial dissolution under the 1939 Act. Zaid countered that triple talaq was valid per community customs and that Ayesha’s employment negated maintenance. Courts, following Iqbal Bano v. State of UP (2007), prioritize Section 125 for destitute women, irrespective of personal law. In 2025, Muslim women increasingly seek judicial remedies, challenging patriarchal practices amid debates over the Uniform Civil Code (UCC), as seen in John Vallamattom v. Union of India (2003). If Ayesha proves destitution, she may secure maintenance, but Zaid’s talaq claim hinges on compliance with the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, 2019, requiring mediation. The case reflects India’s struggle to reconcile personal laws with constitutional equality under Article 14, especially as UCC proposals gain traction.

1. What is the nature of marriage under Muslim personal law?

(A) A sacramental union

(B) A civil contract

(C) A religious obligation

(D) A judicial agreement

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage describes nikah as a civil contract requiring offer, acceptance, and mehr, per Abdul Kadir v. Salima. Option (A) is incorrect, as sacramental unions apply to Hindu law. Option (C) is wrong, as marriage is contractual, not merely religious. Option (D) is incorrect, as judicial agreements are not required for nikah.

2. In the scenario, what legal basis might Ayesha use to challenge Zaid’s triple talaq?

(A) Shayara Bano v. Union of India

(B) Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986

(C) Danial Latifi v. Union of India

(D) Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: A

The passage states Ayesha challenges the talaq’s validity per Shayara Bano (2017), which declared instant triple talaq unconstitutional. Option (B) is incorrect, as the MWPDA governs maintenance, not talaq validity. Option (C) is wrong, as Danial Latifi addressed maintenance duration. Option (D) is incorrect, as the 1939 Act applies to judicial dissolution, not talaq.

3. Which case clarified maintenance rights under Section 125 CrPC for Muslim women?

(A) Iqbal Bano v. State of UP

(B) Shayara Bano v. Union of India

(C) John Vallamattom v. Union of India

(D) Abdul Kadir v. Salima

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: A

The passage cites Iqbal Bano v. State of UP (2007) as prioritizing Section 125 CrPC for destitute Muslim women. Option (B) is incorrect, as Shayara Bano focused on triple talaq. Option (C) is wrong, as John Vallamattom addressed UCC, not maintenance. Option (D) is irrelevant, as Abdul Kadir defined nikah.

4. If Ayesha proves destitution, what remedy might she secure?

(A) Annulment of the nikah

(B) Maintenance under Section 125 CrPC

(C) Restoration of the marriage

(D) Criminal prosecution of Zaid

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage indicates that, per Iqbal Bano, Ayesha may secure maintenance under Section 125 CrPC if destitute. Option (A) is incorrect, as annulment is not sought. Option (C) is wrong, as restoration is not a remedy here. Option (D) is incorrect, as maintenance is a civil remedy, not criminal.

5. What broader issue does the scenario highlight in Muslim personal law?

(A) Reconciling personal laws with constitutional equality

(B) Enforcing international maritime laws

(C) Protecting patent rights

(D) Regulating corporate mergers

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: A

The passage underscores the conflict between Muslim personal law and constitutional equality under Article 14, especially with UCC debates. Option (B) is irrelevant, as maritime laws are not discussed. Option (C) is wrong, as patents are unrelated. Option (D) is incorrect, as mergers are not a family law issue.

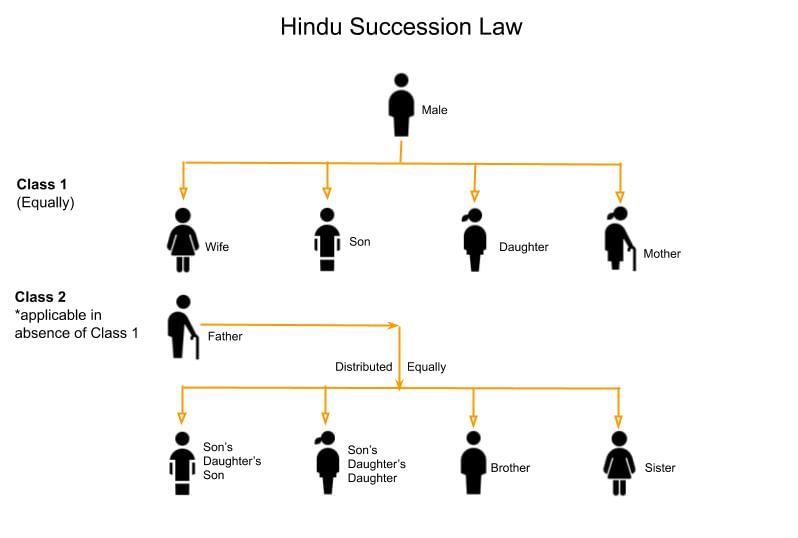

Passage 3: Succession under Hindu Law

The Hindu Succession Act, 1956 (HSA), governs intestate succession among Hindus, promoting gender equality through amendments. Section 6, amended in 2005, grants daughters coparcenary rights equal to sons in ancestral property, as upheld in Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma (2020), which clarified retrospective application. Section 8 outlines general rules for male intestate succession, prioritizing Class I heirs (e.g., children, widow). Section 15 governs female intestate succession, with distinct rules reflecting traditional family structures. In Prakash v. Phulavati (2016), the Supreme Court limited the 2005 amendment’s retrospectivity, later overridden by Vineeta Sharma. Consider a scenario: Ravi, a Hindu, died intestate in 2024, leaving an ancestral house, a self-acquired flat, and savings. His heirs are his widow, Meena; son, Vikram; daughter, Sonia; and mother, Lakshmi. Sonia, married in 2010, claims a coparcenary share in the ancestral house and an equal share in other assets. Vikram argues Sonia’s marriage excludes her from coparcenary rights, citing outdated customs. Meena seeks a share in both ancestral and self-acquired properties, while Lakshmi claims a share as a Class I heir. Under Section 6, Sonia, as a daughter, has coparcenary rights equal to Vikram, per Vineeta Sharma. Section 8 includes Meena, Vikram, Sonia, and Lakshmi as Class I heirs for self-acquired assets, dividing them equally. The HSA’s 2005 amendment, rooted in Article 14’s equality principle, faced resistance in rural India, as seen in Danamma v. Amar (2018), which reinforced daughters’ rights. In 2025, succession disputes reflect tensions between gender reforms and patriarchal norms, with courts prioritizing statutory clarity. If Sonia’s claim succeeds, she may inherit a coparcenary share and an equal portion of self-acquired assets, but Vikram’s objection could delay proceedings. The case also intersects with Uniform Civil Code debates, as in ABC v. State (NCT of Delhi) (2015), advocating secular succession laws.

1. What is the effect of the 2005 amendment to Section 6 of the HSA?

(A) It excludes daughters from coparcenary rights

(B) It grants daughters equal coparcenary rights

(C) It limits succession to Class I heirs

(D) It applies only to self-acquired property

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage states that the 2005 amendment to Section 6 grants daughters coparcenary rights equal to sons, as upheld in Vineeta Sharma. Option (A) is incorrect, as daughters are included, not excluded. Option (C) is wrong, as Section 6 addresses coparcenary, not Class I heirs. Option (D) is incorrect, as it applies to ancestral, not self-acquired, property.

2. In the scenario, who is a Class I heir to Ravi’s self-acquired property?

(A) Vikram only

(B) Meena, Vikram, Sonia, and Lakshmi

(C) Sonia only

(D) Lakshmi only

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage notes that Section 8 includes Meena (widow), Vikram (son), Sonia (daughter), and Lakshmi (mother) as Class I heirs for Ravi’s self-acquired assets. Option (A) is incorrect, as it excludes other heirs. Option (C) is wrong, as Sonia is one of many heirs. Option (D) is incorrect, as Lakshmi is not the sole heir.

3. Which case clarified the retrospective application of the 2005 HSA amendment?

(A) Prakash v. Phulavati

(B) Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma

(C) Danamma v. Amar

(D) ABC v. State (NCT of Delhi)

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage identifies Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma (2020) as clarifying the 2005 amendment’s retrospective application. Option (A) is incorrect, as Prakash v. Phulavati limited retrospectivity, later overridden. Option (C) is wrong, as Danamma reinforced rights but did not clarify retrospectivity. Option (D) is irrelevant, as ABC addressed UCC.

4. If Sonia’s coparcenary claim succeeds, what might she inherit?

(A) Only the self-acquired flat

(B) A share in the ancestral house and self-acquired assets

(C) Nothing, due to her marriage

(D) Only the savings

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: B

The passage confirms Sonia’s coparcenary rights in the ancestral house under Section 6 and her share in self-acquired assets as a Class I heir under Section 8, per Vineeta Sharma. Option (A) is incorrect, as she inherits beyond the flat. Option (C) is wrong, as marriage does not exclude her. Option (D) is incorrect, as her share includes all assets.

5. What broader issue does the scenario highlight in Hindu succession law?

(A) Balancing gender reforms with patriarchal norms

(B) Enforcing international trade agreements

(C) Protecting trademark rights

(D) Regulating corporate insolvency

View Answer

View Answer

Answer: A

The passage highlights the tension between the HSA’s gender equality reforms and patriarchal objections, as seen in Sonia’s claim. Option (B) is irrelevant, as trade agreements are not discussed. Option (C) is wrong, as trademarks are unrelated. Option (D) is incorrect, as insolvency is not a succession issue.

|

63 videos|174 docs|38 tests

|

FAQs on Passage Based Questions on Family Law - Legal Reasoning for CLAT

| 1. What is the Special Marriage Act and how does it differ from personal laws in India? |  |

| 2. What are the eligibility criteria for marriage under the Special Marriage Act? |  |

| 3. How does the process of registration of marriage work under the Special Marriage Act? |  |

| 4. Can individuals from different religions marry under the Special Marriage Act? |  |

| 5. What are the divorce provisions under the Special Marriage Act? |  |