The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 | Legal Reasoning for CLAT PDF Download

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA) is a law in India that governs marriages among Hindus and certain other communities. It was enacted to standardize and regulate Hindu marriages, bringing clarity to their legal aspects. These notes explain the Act in simple language, covering its applicability, the nature of Hindu marriage, and key definitions.

Applicability of the Hindu Marriage Act

The Hindu Marriage Act applies to specific communities in India as defined under Section 2 of the Act. It covers:

- Hindus: People who follow Hinduism by religion.

- Sikhs: Followers of Sikhism.

- Jains: Followers of Jainism.

- Buddhists: Followers of Buddhism.

Who else is included?

- Anyone born as a Hindu, Sikh, Jain, or Buddhist.

- Anyone converted or reconverted to these religions.

- Anyone who is not a Muslim, Christian, Parsi, or Jew and follows Hindu customs or practices.

Note: The Act does not apply to tribal communities unless specifically notified by the government.

Nature of Hindu Marriage

Hindu marriage has evolved over time. Traditionally, it was considered a sacramental union, but the Hindu Marriage Act introduced modern legal elements, making it a blend of sacramental and contractual aspects.

Sacramental Elements

- Hindu marriage is seen as a sacred bond, not just a contract.

- It involves religious ceremonies (like Saptapadi, i.e., seven steps around the sacred fire) that are essential for a valid marriage.

- It is believed to create a lifelong spiritual and emotional connection between the couple.

Contractual Elements

- The Act introduced conditions for a valid marriage (under Section 5), like age, consent, and absence of prohibited relationships.

- It allows legal remedies like divorce, maintenance, and restitution of conjugal rights, which are contractual in nature.

- Marriages can be registered for legal recognition, similar to a contract.

Key Point: The Hindu Marriage Act balances tradition (sacred rituals) with modern law (legal rights and obligations).

Key Definitions (Sections 3 and 5)

The Act provides important definitions to clarify who can marry and under what conditions. These are mainly found in Sections 3 and 5.

a) Definition of "Hindu" (Section 2)

As mentioned earlier, a Hindu under the Act includes not only those who practice Hinduism but also Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, and others who follow Hindu customs or are not followers of other major religions (like Islam or Christianity).

b) Sapinda Relationship (Section 3)

A "sapinda" relationship refers to people who are closely related through a common ancestor. The Act uses this to define who cannot marry each other.

- Rule: A person cannot marry someone within the sapinda relationship unless their custom allows it.

- Example: Cousins may be sapindas, and marriage between them is generally prohibited unless permitted by local customs.

c) Degrees of Prohibited Relationship (Section 3)

The Act lists relationships where marriage is not allowed due to close familial ties. These are called "degrees of prohibited relationship."

Examples:

- A person cannot marry their sibling (brother or sister).

- A person cannot marry their parent, grandparent, or child.

- Marriage with close relatives like aunts, uncles, or first cousins is prohibited unless permitted by custom.

Exception: If a community’s custom allows such marriages, they may be valid.

Conditions for a Valid Hindu Marriage

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA) outlines specific conditions and requirements for a marriage to be legally valid among Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists in India. These conditions are detailed in Sections 5, 7, and 8 of the Act.

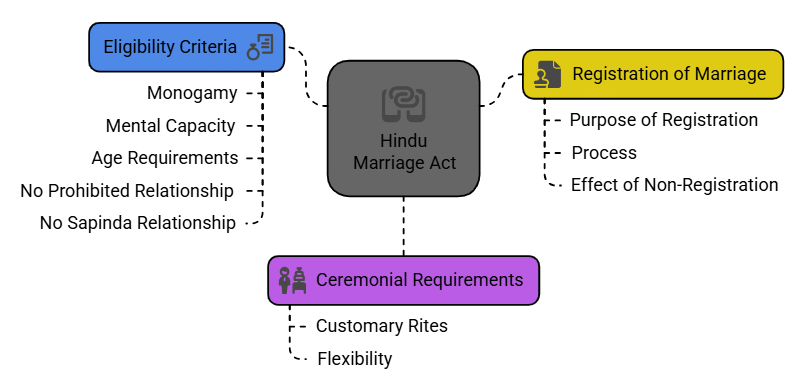

1. Eligibility Criteria (Section 5)

For a Hindu marriage to be valid, both parties must meet certain eligibility conditions as outlined in Section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act. These ensure that the marriage is consensual, legal, and socially acceptable.

- Monogamy: Neither party should have a living spouse at the time of the marriage. This means that both the bride and groom must be single or legally divorced/widowed before entering the marriage.

- Mental Capacity: Both parties must be of sound mind and capable of giving valid consent. They should not suffer from any mental disorder that makes them unfit for marriage or unable to understand the responsibilities of marriage.

- Age Requirements: At the time of marriage, the groom must be at least 21 years old, and the bride must be at least 18 years old.

Note: Recent legislative changes, such as the proposed amendments in 2021, aim to raise the minimum age for brides to 21 to promote gender equality. However, as of April 20, 2025, confirm the current age requirement with the latest legal updates.

- No Prohibited Degree of Relationship: The parties must not be within the "degrees of prohibited relationship" (e.g., siblings, parent-child, or close relatives like aunts/uncles). Marriage within these relationships is not allowed unless permitted by the customs of the community.

- No Sapinda Relationship: The parties must not be "sapindas" of each other, meaning they should not be closely related through a common ancestor (e.g., cousins). This restriction can be overridden if the custom of the community allows such marriages.

Why are these criteria important? They ensure that the marriage is entered into willingly, legally, and in accordance with social norms while respecting customary practices where applicable.

2. Ceremonial Requirements (Section 7)

According to Section 7 of the Hindu Marriage Act, a Hindu marriage must be solemnized in accordance with the customary rites and ceremonies of either the bride or groom’s community. These ceremonies give the marriage its sacramental character.

- Customary Rites: The marriage must include the traditional rituals specific to the couple’s community. Common ceremonies include:

- Saptapadi: The bride and groom take seven steps around a sacred fire, with each step symbolizing a vow. The marriage becomes complete when the seventh step is taken.

- Kanyadaan: The bride’s parents symbolically give her away to the groom.

- Other rituals like applying sindoor (vermilion) or exchanging garlands, depending on regional or community practices.

- Flexibility: The Act allows flexibility in ceremonies as long as they align with the customs of at least one of the parties. For example, a marriage may follow the bride’s community rituals or the groom’s.

Key Point: Without the performance of essential customary rites (like saptapadi, where applicable), the marriage may not be considered valid under the Act.

3. Registration of Marriage (Section 8)

Section 8 of the Hindu Marriage Act provides for the registration of marriages to ensure legal recognition and documentation. While registration is optional, it is highly encouraged.

- Purpose of Registration: Registering a marriage provides official proof of the marriage, which is useful for legal purposes such as inheritance, property rights, or visa applications.

- Process: The couple can register their marriage with the local Registrar of Marriages by submitting details like the date, place, and proof of the marriage ceremony (e.g., photographs or witness statements).

- Effect of Non-Registration: A marriage is still valid if it meets the conditions of Sections 5 and 7, even if it is not registered. However, non-registration may create difficulties in proving the marriage in legal disputes.

Why register? Registration strengthens the legal standing of the marriage and protects the rights of both spouses, especially in matters like divorce, maintenance, or inheritance.

Solemnization of Hindu Marriage and Legal Implications

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA) governs the solemnization of marriages among Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists in India. This document explains the forms of marriage, customary variations, the importance of registration, and the concepts of void and voidable marriages in simple language, as outlined in the relevant sections of the Act.

1. Solemnization of Marriage

Solemnization refers to the process of performing a marriage with the necessary ceremonies and rituals, as recognized under Section 7 of the Hindu Marriage Act. The Act accommodates both traditional and modern practices while respecting regional and community-specific customs.

a) Forms of Marriage

Hindu marriages can take various forms, reflecting cultural, social, and personal preferences. The Act recognizes the following types:

- Traditional Arranged Marriages: Families select the bride and groom based on factors like caste, religion, and horoscope compatibility. These marriages often involve elaborate rituals and parental involvement.

- Love Marriages: The couple chooses each other based on mutual affection, with or without family approval. Love marriages are increasingly common and legally valid if they meet the Act’s conditions.

- Inter-Caste Marriages: Marriages between individuals of different castes. These are legally valid and encouraged under modern laws to promote social integration, though they may face social resistance in some communities.

Key Point: The Hindu Marriage Act does not discriminate between arranged, love, or inter-caste marriages as long as the legal and ceremonial requirements are met.

b) Customary Variations

Hindu marriages vary widely across regions and communities, and the Act allows flexibility in the performance of rituals under Section 7. The marriage must follow the customary rites of either the bride or groom’s community.

- Examples of Regional Rituals:

- Saptapadi (North India): The couple takes seven steps around a sacred fire, with each step symbolizing a vow.

- Kanyadaan (Common in many regions): The bride’s parents symbolically give her to the groom.

- Mangalsutra (South India, Maharashtra): The groom ties a sacred thread around the bride’s neck.

- Exchange of Garlands (Various regions): The couple exchanges garlands as a symbol of mutual acceptance.

- Community-Specific Practices: Different communities, such as Tamil Brahmins, Punjabi Sikhs, or Bengali Hindus, have unique rituals. For example, Tamil marriages may include the “Oonjal” ceremony (swinging ritual), while Sikh marriages involve the “Anand Karaj” (circumambulation around the Guru Granth Sahib).

Note: The essential ceremonies (e.g., saptapadi, where applicable) must be performed for the marriage to be legally valid. The Act respects the diversity of Hindu customs.

c) Legal Recognition: Importance of Registration

Under Section 8, marriage registration is optional but highly recommended for legal recognition and evidentiary purposes.

Why Register?

- Provides official proof of marriage, useful for legal matters like inheritance, property disputes, or visa applications.

- Protects the rights of spouses, especially in cases of divorce, maintenance, or custody disputes.

- Simplifies verification of marital status in legal or administrative processes.

- Process: The couple can register their marriage with the local Registrar of Marriages by submitting details such as the date, place, and proof of the ceremony (e.g., photographs, witness statements).

- Effect of Non-Registration: A marriage is still valid if it meets the conditions of Sections 5 and 7, but non-registration may complicate proving the marriage in legal disputes.

Key Benefit: Registration strengthens the legal standing of the marriage and safeguards the couple’s rights.

2. Void and Voidable Marriages

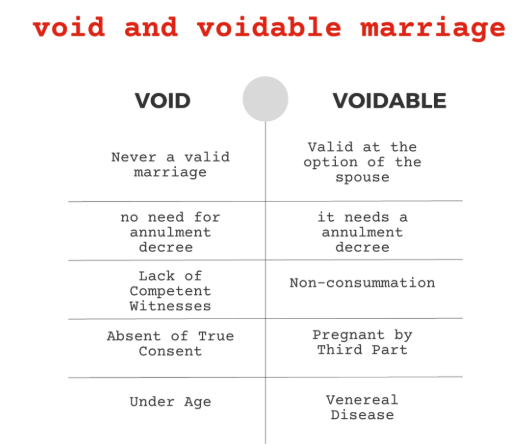

The Hindu Marriage Act distinguishes between void and voidable marriages, which determine whether a marriage is invalid from the start or can be annulled under certain conditions.

a) Void Marriages (Section 11)

A void marriage is one that is invalid from the beginning and has no legal effect. It is treated as if the marriage never existed. Section 11 lists conditions under which a marriage is void:

- Bigamy: Either party has a living spouse at the time of the marriage (violates the monogamy rule under Section 5).

- Prohibited Degree of Relationship: The parties are within the degrees of prohibited relationship (e.g., siblings, parent-child) unless permitted by custom.

- Sapinda Relationship: The parties are sapindas (closely related through a common ancestor) unless allowed by custom.

Consequence: A void marriage does not require a court order to be declared invalid, but parties may seek a formal declaration for clarity in legal matters.

b) Voidable Marriages (Section 12)

A voidable marriage is valid until it is annulled by a court order. Section 12 lists grounds on which a marriage can be annulled at the request of one of the parties:

- Fraud: One party was misled or deceived into the marriage (e.g., hiding a serious illness or misrepresenting identity).

- Impotence: One party is unable to consummate the marriage due to impotence.

- Non-Consummation: The marriage has not been consummated due to the willful refusal of one party.

- Pregnancy by Another Person: The bride was pregnant by someone other than the groom at the time of marriage, and the groom was unaware of it.

- Lack of Consent: The consent of either party was obtained by force or coercion, or they were not of sound mind to give valid consent.

Key Difference: Unlike void marriages, voidable marriages are valid until a court annuls them. The affected party must file a petition for annulment.

Rights and Obligations in Hindu Marriage

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA) outlines the rights and obligations of spouses in a Hindu marriage, emphasizing mutual responsibilities and legal remedies. This document explains conjugal rights, restitution of conjugal rights, maintenance, and matrimonial property in simple language, along with relevant legal provisions and judicial interpretations.

1. Conjugal Rights

Conjugal rights refer to the mutual rights and duties of spouses arising from the marriage, including the right to live together and provide emotional, physical, and financial support.

- Right to Cohabitation: Both spouses have the right to live together and share a marital home. This includes companionship and the opportunity to build a family.

- Mutual Support: Spouses are expected to support each other emotionally, socially, and financially, contributing to the well-being of the family.

- Obligations: Both parties must fulfill their marital duties, such as maintaining fidelity, respecting each other, and cooperating in household responsibilities.

Key Point: Conjugal rights form the foundation of a Hindu marriage, reflecting its sacramental and contractual nature under the HMA.

2. Restitution of Conjugal Rights (Section 9)

Under Section 9 of the HMA, if one spouse withdraws from the society of the other without a reasonable cause, the aggrieved spouse can seek a legal remedy called restitution of conjugal rights.

- What It Means: This remedy allows a spouse to file a petition in court to request that the other spouse return to cohabitation and resume marital duties.

- Conditions:

- The withdrawing spouse must have left without a reasonable cause (e.g., no valid reason like cruelty or abuse).

- The petitioner must genuinely want to restore the marital relationship.

- Process: The court may issue an order directing the withdrawing spouse to return and live with the petitioner. If the order is not followed, it may impact related legal proceedings (e.g., divorce or maintenance).

- Limitations: Courts are cautious in enforcing this remedy, as forcing cohabitation may not always be practical or fair, especially in cases of domestic violence or irreconcilable differences.

Note: Restitution of conjugal rights aims to preserve the marriage, but its enforcement is controversial due to concerns about personal autonomy and consent.

3. Maintenance

Maintenance refers to the financial support one spouse may be entitled to from the other during marriage or after separation. The HMA, along with Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), provides for maintenance, particularly to protect the financially dependent spouse (often the wife).

- Under the HMA:

- Section 24: Either spouse can seek pendente lite (temporary) maintenance during ongoing matrimonial proceedings (e.g., divorce or restitution cases) if they lack sufficient income.

- Section 25: Permanent alimony or maintenance can be granted after the final decree in cases like divorce or judicial separation, based on factors like the spouse’s income, needs, and lifestyle.

- Under Section 125 CrPC:

- A wife (or in some cases, a husband) unable to maintain themselves can seek monthly maintenance from the spouse with sufficient means.

- This applies even if the couple is living separately, provided the claimant has a justifiable reason (e.g., cruelty, desertion, or neglect).

- Eligibility: Maintenance is typically awarded to the wife, but a husband may claim it if he is incapacitated and the wife has sufficient income. Courts consider factors like income disparity, living expenses, and the duration of the marriage.

- Judicial Trends: Courts often prioritize the wife’s right to a dignified life, especially in cases of abandonment or divorce, ensuring she is not left destitute.

Why It Matters: Maintenance ensures financial security for the dependent spouse, promoting fairness and protecting vulnerable parties in a marriage.

4. Matrimonial Property

The Hindu Marriage Act does not provide a specific regime for the division or management of matrimonial property (assets acquired during the marriage). However, judicial interpretations, customs, and related laws govern this aspect.

- No Statutory Framework in HMA: Unlike some countries with clear laws on matrimonial property (e.g., community property systems), the HMA is silent on how assets like the marital home, savings, or joint investments are divided.

- Judicial Interpretations:

- Courts often rely on principles of equity and fairness when dividing property in divorce or separation cases.

- The concept of Stridhan (a woman’s exclusive property, like gifts or jewelry received during marriage) is recognized, and the wife retains full rights over it.

- In some cases, courts may consider contributions (financial or non-financial, like homemaking) to determine a spouse’s share in joint property.

- Customary Practices: In many Hindu communities, property division follows traditional norms. For example, ancestral property may be governed by Hindu succession laws, while personal assets may be divided based on mutual agreement or court orders.

- Related Laws:

- The Hindu Succession Act, 1956, governs inheritance of property, which may apply to spouses after the death of one partner.

- The Domestic Violence Act, 2005, grants a wife the right to reside in the matrimonial home, even if it is not in her name, to prevent homelessness.

Key Insight: While the HMA lacks a clear matrimonial property regime, courts use discretion and related laws to ensure fair division, especially protecting the wife’s rights to Stridhan and residence.

Divorce and Judicial Separation under Hindu Marriage Act

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA) provides legal provisions for divorce and judicial separation, allowing spouses to either dissolve their marriage or live separately without ending it. Section 13 outlines the grounds for divorce, including fault-based grounds, special grounds for wives, and mutual consent divorce. Section 10 governs judicial separation. Additionally, courts have recognized the irretrievable breakdown of marriage in specific cases. This document explains these concepts in simple language.

1. Grounds for Divorce (Section 13)

Divorce under the HMA can be sought on various grounds, primarily categorized as fault-based grounds (Section 13(1)), special grounds for wives (Section 13(2)), and mutual consent (Section 13B).

a) Fault-Based Grounds (Section 13(1))

These are reasons where one spouse’s actions or conditions justify the other seeking divorce. The grounds include:

- Adultery: One spouse has a voluntary sexual relationship with someone other than their spouse. Proof of infidelity is required.

- Cruelty: Physical or mental cruelty that makes it unsafe or unbearable for the other spouse to live with the offending spouse. Examples include physical abuse, verbal insults, or harassment.

- Desertion: One spouse abandons the other without reasonable cause for a continuous period of at least 2 years before filing for divorce.

- Conversion to Another Religion: One spouse converts to another religion (e.g., from Hinduism to Islam), ceasing to be a Hindu.

- Unsound Mind or Mental Disorder: One spouse suffers from a mental disorder or is of unsound mind to the extent that the other cannot reasonably live with them.

- Venereal Disease: One spouse has a communicable venereal disease (e.g., HIV/AIDS) that endangers the other.

- Leprosy: One spouse suffers from an incurable form of leprosy. (Note: This ground is rarely invoked today due to medical advancements.)

- Non-Resumption of Cohabitation: The spouses have not resumed living together after a decree of judicial separation or restitution of conjugal rights for at least 1 year.

Key Point: Fault-based grounds require the petitioner to prove the other spouse’s fault, which may involve presenting evidence like witnesses or medical reports.

b) Special Grounds for Wife (Section 13(2))

Section 13(2) provides additional grounds exclusively for wives to seek divorce, addressing specific vulnerabilities:

- Husband’s Bigamy: The husband has married another woman before the wife’s marriage was dissolved, violating the monogamy rule.

- Rape, Sodomy, or Bestiality by Husband: The husband has been guilty of these criminal acts, providing grounds for the wife to seek divorce.

- Non-Resumption of Cohabitation After Maintenance Decree: If the wife has obtained a maintenance order (e.g., under Section 125 CrPC) and the spouses have not resumed cohabitation for at least 1 year, she can seek divorce.

- Repudiation of Marriage (Option of Puberty): If the wife was married before she was 15 years old, she can repudiate the marriage after turning 15 but before reaching 18 years, provided the marriage was not consummated.

Why These Grounds?: These provisions protect wives from specific wrongs, recognizing their social and legal vulnerabilities in marriage.

c) Irretrievable Breakdown of Marriage

The HMA does not explicitly recognize the irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground for divorce. However, courts, particularly the Supreme Court, have granted divorces in cases where the marriage is irreparably broken, invoking Article 142 of the Constitution to do complete justice.

- Meaning: The marriage has deteriorated to a point where reconciliation is impossible, and continuing it serves no purpose (e.g., long-term separation or mutual hostility).

- Judicial Approach: Courts assess factors like the duration of separation, attempts at reconciliation, and the spouses’ conduct. For example, a marriage with no cohabitation for several years may be deemed irretrievably broken.

- Limitations: This ground is applied sparingly and requires judicial discretion, as it is not codified in the HMA.

Note: The recognition of irretrievable breakdown reflects modern judicial trends but is not a standard ground under the HMA.

Mutual Consent Divorce (Section 13B)

Under Section 13B, spouses can seek divorce by mutual consent, a no-fault option where both agree to end the marriage amicably.

- Requirements:

- Both spouses must mutually agree to dissolve the marriage.

- They must have lived separately for at least 1 year before filing the petition.

- They must show that they cannot live together and have freely consented to the divorce.

- Filing Procedure:

- The spouses file a joint petition in a family court.

- After filing, there is a mandatory 6-month cooling-off period to allow for reconciliation.

- After 6 months (and within 18 months), the spouses file a second motion confirming their decision. The court then grants the divorce if satisfied.

- Waiver of Cooling-Off Period: Courts may waive the 6-month period if reconciliation is impossible or the delay would cause undue hardship, as per Supreme Court rulings (e.g., Amardeep Singh v. Harveen Kaur, 2017).

Advantage: Mutual consent divorce is faster and less adversarial, as it avoids proving fault and focuses on mutual agreement.

Judicial Separation (Section 10)

Judicial separation, governed by Section 10, is an alternative to divorce. It allows spouses to live separately without dissolving the marriage, preserving the legal status of marriage.

- Meaning: The court grants a decree allowing spouses to live apart while remaining legally married. They are relieved of cohabitation duties but cannot remarry.

- Grounds: The grounds for judicial separation are the same as those for divorce under Section 13(1) (e.g., adultery, cruelty, desertion) and Section 13(2) for wives.

- Purpose:

- Provides a cooling-off period for reconciliation.

- Protects spouses from unwanted cohabitation, especially in cases of cruelty or abuse.

- Allows financial support (e.g., maintenance) without ending the marriage.

- Effect: If the spouses do not resume cohabitation for 1 year after a judicial separation decree, either can seek divorce under Section 13(1).

Key Difference: Unlike divorce, judicial separation does not end the marriage, offering a middle ground for spouses unsure about permanent dissolution.

Maintenance and Alimony under Hindu Marriage Act

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA) provides for financial support to spouses through maintenance and alimony, ensuring economic security during and after matrimonial disputes. Section 24 governs temporary maintenance during litigation, while Section 25 addresses permanent alimony post-divorce. Key judicial guidelines, such as those in Rajnesh v. Neha, help determine the quantum of maintenance.

1. Maintenance Pendente Lite (Section 24)

Section 24 of the HMA allows either spouse to seek temporary maintenance and litigation expenses during the pendency of matrimonial proceedings, such as divorce, judicial separation, or restitution of conjugal rights.

- Purpose: To ensure that a financially dependent spouse (often the wife) can sustain themselves and afford legal costs during the case.

- Eligibility:

- Either spouse (husband or wife) can apply if they lack sufficient income or resources.

- The applicant must show financial need, and the other spouse must have the means to pay.

- Scope:

- Maintenance: Covers living expenses, such as food, clothing, and shelter, during the litigation.

- Litigation Expenses: Includes legal fees, court costs, and other related expenses.

- Factors Considered: Courts assess the income, assets, lifestyle, and financial disparity between the spouses. The goal is to provide reasonable support without overburdening the paying spouse.

- Duration: Maintenance under Section 24 is temporary and lasts only until the matrimonial proceedings are concluded.

Key Point: Section 24 ensures that financial constraints do not prevent a spouse from pursuing or defending a matrimonial case, promoting access to justice.

2. Permanent Alimony (Section 25)

Section 25 of the HMA provides for permanent alimony or maintenance to be granted after the final decree in matrimonial proceedings, such as divorce or judicial separation, to support the financially dependent spouse.

- Purpose: To ensure the dependent spouse (typically the wife) can maintain a reasonable standard of living post-divorce or separation, especially if they lack independent income.

- Eligibility:

- Either spouse can apply, though it is more commonly awarded to the wife.

- The applicant must demonstrate financial need, and the other spouse must have the capacity to pay.

- Forms of Alimony:

- Periodic Payments: Monthly or regular payments for a specified period or indefinitely.

- Lump-Sum Payment: A one-time payment to settle all future maintenance claims.

- Factors Considered: Courts evaluate several factors to determine the quantum and nature of alimony, including:

- Income and Property: The income, assets, and earning capacity of both spouses.

- Conduct of Parties: The behavior of spouses during the marriage, such as cruelty, adultery, or abandonment, may influence the amount.

- Standard of Living: The lifestyle enjoyed during the marriage.

- Needs and Obligations: The financial needs of the applicant and any obligations of the paying spouse (e.g., supporting children or other dependents).

- Duration of Marriage: Longer marriages may result in higher alimony, especially if the dependent spouse sacrificed career opportunities.

- Modification or Termination: The court can modify or cancel alimony if circumstances change, such as the recipient remarrying, becoming financially independent, or engaging in misconduct.

Why It Matters: Permanent alimony under Section 25 protects the economically weaker spouse from destitution and ensures fairness post-divorce.

3. Relevant Case Law: Principles for Determining Quantum

Judicial decisions have established guidelines for determining the quantum of maintenance and alimony, ensuring consistency and fairness. A landmark case is Rajnesh v. Neha (2020), which provides comprehensive principles for maintenance under various laws, including the HMA.

Rajnesh v. Neha (2020)

In this Supreme Court case, the court laid down detailed guidelines to standardize maintenance awards, addressing issues like overlapping claims and arbitrary amounts.

- Key Principles:

- Financial Capacity: Maintenance should be based on the paying spouse’s income and liabilities, ensuring it is neither excessive nor inadequate.

- Reasonable Needs: The amount should meet the recipient’s basic needs (food, clothing, shelter, medical expenses) while considering their pre-separation lifestyle.

- Earning Capacity: Courts must assess whether the applicant can earn independently, but homemaking contributions are equally valued.

- Children’s Expenses: Maintenance for children (e.g., education, healthcare) should be factored in separately or alongside spousal maintenance.

- Disclosure of Income: Both spouses must submit affidavits disclosing their income, assets, and liabilities to ensure transparency.

- Avoiding Double Payments: Courts should avoid granting maintenance under multiple laws (e.g., HMA and Section 125 CrPC) for the same purpose, adjusting amounts to prevent overlap.

- Timely Disposal: Maintenance cases should be resolved promptly to avoid prolonged financial hardship.

- Impact: The guidelines apply to maintenance under the HMA, Section 125 CrPC, and other laws, ensuring uniformity. They emphasize fairness, transparency, and the protection of the dependent spouse’s dignity.

Other Notable Cases

- Vinny Parmar v. Paramvir Parmar (2011): The Supreme Court held that the wife’s earning capacity or employment does not automatically disqualify her from maintenance if her income is insufficient to maintain the marital standard of living.

- Shamima Farooqui v. Shahid Khan (2015): The court emphasized that maintenance is a right of the wife to live with dignity, not merely to survive, and should reflect her social and economic status.

Key Insight: Cases like Rajnesh v. Neha provide a structured approach to maintenance, balancing the needs of the recipient with the paying spouse’s capacity, while prioritizing fairness and transparency.

Child Custody, Guardianship, and Ancillary Issues in Hindu Law

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA), along with related laws like the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956 (HMGA), Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956 (HAMA), Hindu Succession Act, 1956 (HSA), and the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA), governs child custody, guardianship, and ancillary issues in Hindu marriages. This document explains child custody post-divorce, guardianship, and related issues like adoption, maintenance, domestic violence, and inheritance in simple language.

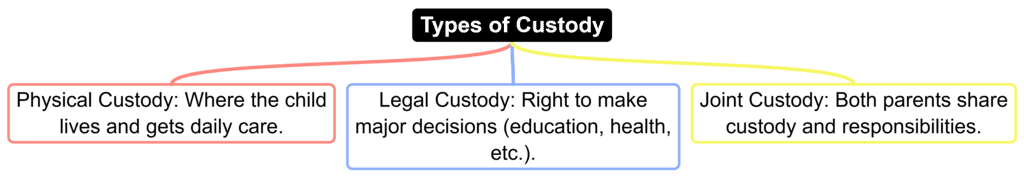

1. Child Custody Post-Divorce

Child custody refers to the care, control, and maintenance of a minor child (under 18 years) after the parents’ divorce or separation. The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956, and judicial principles guide custody decisions, with the welfare of the child being the paramount consideration.

b) Paramount Consideration: Welfare of the Child

Under the HMGA and judicial precedents, the child’s welfare is the primary factor in custody decisions. Courts consider:

- Child’s Age and Needs: Younger children, especially infants, may be placed with the mother unless she is unfit. Older children’s preferences may be considered.

- Parental Fitness: The physical, mental, and financial capacity of each parent to care for the child.

- Stability: The ability to provide a stable, nurturing environment, including housing and education.

- Child’s Emotional Bond: The strength of the child’s relationship with each parent.

- Safety: Absence of abuse, neglect, or domestic violence in the parent’s household.

Key Principle: The child’s best interests override parental preferences or rights, ensuring their physical, emotional, and psychological well-being.

c) Visitation Rights

The non-custodial parent (who does not have physical custody) is typically granted visitation rights to maintain a relationship with the child, unless it is detrimental to the child’s welfare.

- Forms of Visitation: Regular visits (e.g., weekends), holiday visits, or supervised visits (if safety concerns exist).

- Court’s Role: Courts may specify visitation schedules to ensure the child’s access to both parents while prioritizing stability.

- Restrictions: Visitation may be denied or limited if the non-custodial parent poses a risk (e.g., history of abuse).

Note: Visitation rights balance the non-custodial parent’s role with the child’s welfare, fostering healthy parent-child relationships post-divorce.

2. Guardianship

Guardianship involves the legal authority to care for a minor child and make decisions on their behalf. The HMGA, 1956, governs guardianship for Hindus.

Natural Guardian:

- For a minor child (under 18), the father is the natural guardian, followed by the mother if the father is deceased, unfit, or absent.

- For a minor boy or unmarried girl, the mother is the natural guardian for children under 5 years, after which the father assumes primacy, unless the court rules otherwise.

- Court-Appointed Guardians: If neither parent is suitable (e.g., due to incapacity, abuse, or neglect), the court may appoint a guardian, such as a relative or a third party, prioritizing the child’s welfare.

- Role of Guardian: Manage the child’s property, education, and overall well-being until the child reaches adulthood.

Key Point: Guardianship under the HMGA ensures a responsible adult oversees the child’s interests, with courts intervening to protect the child if needed.

Ancillary Issues

Child custody and guardianship intersect with other legal issues, including adoption, maintenance, domestic violence, and inheritance, governed by related statutes.

a) Adoption and Maintenance

The Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956 (HAMA) addresses adoption and maintenance obligations, which are linked to custody and guardianship.

- Adoption:

- HAMA governs adoption among Hindus, allowing a married couple, single person, or divorced parent to adopt, subject to conditions (e.g., consent of the custodial parent).

- Post-divorce, adoption by one parent may require the other parent’s consent or court approval, especially if they retain legal custody or guardianship rights.

- An adopted child has the same rights as a biological child, including custody, maintenance, and inheritance.

- Maintenance:

- Under Section 20 of HAMA, parents are obligated to maintain their minor children (biological or adopted), whether legitimate or illegitimate.

- In custody disputes, the custodial parent may seek maintenance from the non-custodial parent to cover the child’s expenses (e.g., education, healthcare).

- Courts consider the parents’ income and the child’s needs, as guided by cases like Rajnesh v. Neha (2020).

Linkage: Adoption and maintenance ensure the child’s financial and emotional security, complementing custody arrangements.

b) Domestic Violence

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA) intersects with custody and guardianship, particularly when domestic violence affects the child or custodial parent. Relevance to Custody:

Relevance to Custody:

- Evidence of domestic violence (physical, emotional, or economic) against the custodial parent or child may influence custody decisions, often favoring the non-abusive parent.

- Courts may deny custody or visitation to a parent with a history of violence to protect the child’s welfare.

Reliefs under PWDVA:

- Protection Orders: Restrict the abusive parent from contacting the child or custodial parent.

- Residence Orders: Ensure the custodial parent (usually the mother) and child can remain in the matrimonial home.

- Monetary Relief: Provide maintenance for the child and the abused spouse.

- Impact on Guardianship: A parent guilty of domestic violence may be deemed unfit as a natural guardian, prompting court intervention to appoint an alternative guardian.

Key Role: The PWDVA safeguards the child and custodial parent from abuse, ensuring a safe environment during custody disputes.

c) Inheritance and Succession

The Hindu Succession Act, 1956 (HSA) governs inheritance rights, which are influenced by marital status and custody arrangements.

Impact of Marital Status:

- A divorced spouse does not inherit from the ex-spouse’s property under the HSA, but children retain inheritance rights from both parents, regardless of custody.

- If the parents are separated but not divorced, the spouse and children remain eligible to inherit as Class I heirs (e.g., wife, children, mother).

Children’s Rights:

- Children (biological or adopted) are entitled to an equal share of the parent’s property, whether ancestral or self-acquired, under Section 8 of HSA.

- Custody does not affect inheritance rights, but the guardian manages the child’s inherited property until they reach adulthood.

- Judicial Considerations: Courts may ensure that maintenance or alimony orders account for the child’s inheritance rights to avoid financial dependency.

Key Insight: The HSA ensures that children’s inheritance rights are protected, regardless of the parents’ marital status or custody arrangements.

Judicial Precedents and Recent Developments in Hindu Marriage Law

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA) has been shaped by significant judicial precedents and evolving legal trends. Key court rulings have clarified issues like bigamy, maintenance, divorce, and inheritance, while recent legislative proposals and judicial interpretations reflect modern societal needs. This document explains important case law, recent developments, and the interplay with customary practices and other laws in simple language.

1. Judicial Precedents

Landmark cases have played a crucial role in interpreting and expanding the scope of the HMA, addressing complex issues in marriage, divorce, and related rights.

a) Sarla Mudgal v. Union of India (1995)

Issue: Bigamy and conversion to another religion.

- Facts: The case involved Hindu husbands converting to Islam to marry a second wife without dissolving their first Hindu marriage, exploiting the absence of monogamy laws in Muslim personal law.

- Ruling: The Supreme Court held that conversion to another religion does not automatically dissolve a Hindu marriage. A second marriage during the subsistence of the first is void under Section 11 of HMA and constitutes bigamy under Section 494 of the Indian Penal Code.

- Impact: The ruling reinforced the monogamy principle in Hindu law and emphasized that conversion cannot be used to circumvent legal obligations. It also sparked discussions on the need for a Uniform Civil Code (UCC).

Key Takeaway: Conversion does not exempt a spouse from the HMA’s monogamy rule, protecting the rights of the first spouse.

b) Naveen Kohli v. Neelu Kohli (2006)

Issue: Irretrievable breakdown of marriage.

- Facts: The couple faced prolonged marital discord with mutual allegations of cruelty, leading to a complete breakdown of their relationship.

- Ruling: The Supreme Court granted divorce, recognizing the irretrievable breakdown of marriage, even though it is not a statutory ground under the HMA. The court invoked Article 142 of the Constitution to do complete justice, noting that continuing the marriage would cause further harm.

- Impact: The case set a precedent for granting divorce in cases of irreparable marital breakdown, influencing subsequent rulings and legislative debates on including this ground in the HMA.

Key Takeaway: Courts may dissolve a marriage if it is irretrievably broken, prioritizing practical justice over strict statutory grounds.

c) Shamima Farooqui v. Shahid Khan (2015)

Issue: Maintenance rights of a wife.

- Facts: The wife sought maintenance under Section 125 of the CrPC after being neglected by her husband, who argued she could support herself.

- Ruling: The Supreme Court held that a wife’s right to maintenance is absolute, ensuring she can live with dignity, not merely survive. The court emphasized that maintenance should reflect the marital standard of living and the husband’s financial capacity.

- Impact: The ruling strengthened maintenance rights under both the HMA and CrPC, affirming the wife’s entitlement to a dignified life post-separation.

Key Takeaway: Maintenance is a fundamental right to ensure the wife’s economic security and dignity, regardless of her ability to earn.

d) Danamma v. Amar (2018)

Issue: Women’s inheritance rights post-marriage.

- Facts: The case involved a daughter’s claim to her father’s property under the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 (HSA), amended in 2005 to grant daughters equal coparcenary rights.

- Ruling: The Supreme Court clarified that daughters, whether married or unmarried, have equal rights to ancestral property as sons, effective from the 2005 amendment. The ruling applied retrospectively to daughters born before the amendment.

- Impact: The decision empowered married women by ensuring their inheritance rights in their natal family’s property, aligning with gender equality principles.

Key Takeaway: The 2005 HSA amendment grants daughters equal inheritance rights, significantly impacting married women’s property entitlements.

e) Amardeep Singh v. Harveen Kaur (2017)

Issue: Waiver of cooling-off period in mutual consent divorce.

- Facts: The couple sought divorce by mutual consent under Section 13B of HMA but requested a waiver of the mandatory 6-month cooling-off period due to irreconcilable differences.

- Ruling: The Supreme Court held that the 6-month cooling-off period can be waived if the court is satisfied that reconciliation is impossible and the delay would cause undue hardship. The decision prioritized the parties’ mutual consent and practical circumstances.

- Impact: The ruling streamlined mutual consent divorces, reducing unnecessary delays and facilitating amicable separations.

Key Takeaway: Courts can waive the cooling-off period in mutual consent divorces to expedite justice when reconciliation is futile.

Recent Developments and Reforms

The HMA continues to evolve through legislative proposals, judicial trends, and the interplay with customary practices and other laws, reflecting changing social realities.

a) Legislative Changes

Recent proposals aim to amend the HMA to align with modern gender equality and social norms.

- Raising Women’s Marriageable Age: In 2021, the Indian government proposed amending the HMA to raise the minimum marriageable age for women from 18 to 21, matching the age for men. The Prohibition of Child Marriage (Amendment) Bill, 2021, seeks to promote gender equality, improve women’s education, and reduce health risks from early marriages. As of April 20, 2025, check the status of this bill to confirm its enactment.

Significance: Raising the marriageable age aims to empower women by ensuring greater maturity and opportunities before marriage.

b) Judicial Trends

Courts have adopted progressive interpretations of the HMA to address contemporary issues.

- Liberal Interpretation of Cruelty: Courts have expanded the definition of cruelty under Section 13(1)(ia) to include mental cruelty, such as persistent harassment, humiliation, or emotional neglect. Cases like V. Bhagat v. D. Bhagat (1994) recognize that mental cruelty can be grounds for divorce even without physical abuse.

- Recognition of Irretrievable Breakdown: Following Naveen Kohli v. Neelu Kohli, courts increasingly grant divorces for irretrievable breakdown using Article 142, though it remains non-statutory. This reflects a shift toward practical solutions in irreparable marriages.

- Gender-Neutral Maintenance: Judicial rulings, such as Rajnesh v. Neha (2020), emphasize that maintenance under Section 24 and Section 25 of HMA can be awarded to either spouse based on financial need, promoting gender neutrality. Courts also ensure transparency through income disclosures.

Trend: Courts are balancing traditional HMA provisions with modern principles of equality and practicality.

c) Customary Practices

Customary practices remain relevant in Hindu marriages and divorces, as recognized by the HMA.

- Customary Divorce: Certain communities, such as those in tribal or rural areas, follow customary divorce practices (e.g., mutual agreement or community mediation). The HMA under Section 29 upholds such customs if they are established and not against public policy.

- Marriage Rituals: Customs like saptapadi or regional rituals (e.g., mangalsutra in South India) continue to define valid marriages under Section 7, ensuring cultural diversity is respected.

Significance: The HMA integrates customary practices, allowing flexibility while ensuring legal oversight.

d) Interplay with Other Laws

The HMA interacts with secular and personal laws, influencing ongoing debates about family law reforms.

- Uniform Civil Code (UCC): Cases like Sarla Mudgal have fueled discussions on a UCC to standardize personal laws across religions, addressing issues like bigamy and conversion. As of April 20, 2025, the UCC remains a proposal, with no nationwide implementation.

- Special Marriage Act, 1954 (SMA): The SMA governs inter-religious or secular marriages and is often compared with the HMA. Couples married under the SMA may face different rules for divorce or inheritance, prompting debates on harmonizing personal laws.

- Secular Laws: Laws like the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, and Section 125 of CrPC complement the HMA, providing additional protections (e.g., maintenance, residence rights) in marital disputes.

Key Debate: The interplay between the HMA and other laws highlights the tension between personal laws and uniform legal standards, shaping future reforms.

Conclusion

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, effectively balances traditional Hindu values with modern legal principles, governing marriage, divorce, maintenance, custody, and guardianship for Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists. Key judicial precedents like Sarla Mudgal (bigamy) and Rajnesh v. Neha (maintenance) have clarified and expanded its provisions. Recent reforms, such as raising the women’s marriageable age, and liberal interpretations of cruelty reflect its adaptability. Complementing other laws like the Hindu Succession Act and Domestic Violence Act, the HMA ensures fairness and dignity while respecting customs, making it a dynamic framework for family law in India.

|

63 videos|174 docs|38 tests

|

FAQs on The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 - Legal Reasoning for CLAT

| 1. What were the traditional forms of Hindu marriage before the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 ? |  |

| 2. What are the key changes introduced by the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 ? |  |

| 3. What are the essentials of a valid Hindu marriage according to the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 ? |  |

| 4. What are some other essential provisions related to Hindu marriage under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 ? |  |

| 5. How has the institution of marriage evolved within Hindu society over time ? |  |