Vivek Singh Summary Agriculture - 1 | Indian Economy for UPSC CSE PDF Download

Introduction

Agriculture plays a vital role in the Indian economy, contributing significantly to the Gross Value Added (GVA). Despite the overall growth of the economy and the increasing share of other sectors such as manufacturing and services, agriculture remains a crucial sector, especially for rural employment and livelihood.

- The agricultural sector includes activities such as the cultivation of crops, horticulture, animal husbandry, fishing, aquaculture, and forestry. These activities not only provide food and raw materials but also contribute to the rural economy and employment.

- The contribution of agriculture to the GVA has been relatively stable, hovering around 18% to 20% over the years. This stability is noteworthy given the rapid growth of other sectors. The share of agriculture in the total GVA reflects its importance in providing food security and supporting rural livelihoods.

Growth Trends:

- The agricultural sector has experienced fluctuations in growth rates, with periods of robust growth followed by slowdowns. For instance, in 2016-17, the sector grew by 6.8%, while in 2018-19, the growth rate was 2.10%.

- Such fluctuations are often influenced by factors such as monsoon patterns,pest outbreaks, and changes in global commodity prices.

Structural Changes:

- Over the years, there has been a gradual shift in the composition of the agricultural sector. The share of food grains in the total agricultural output has declined, while the share of horticulture and livestock products has increased.

- This shift indicates changing consumption patterns and the increasing importance of high-value crops and animal products in the diet.

Policy Support:

- The Indian government has implemented various policies to support the agricultural sector, including minimum support prices (MSP) for certain crops, which ensure farmers a fair price for their produce.

- Additionally, schemes such as Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) provide direct income support to farmers, helping to improve their financial stability.

Challenges:

- Despite its importance, the agricultural sector faces several challenges, including climate change, which affects rainfall patterns and temperature, making agriculture more unpredictable.

- Other challenges include the need for modernization of agricultural practices, access to credit for farmers, and improving infrastructure such as roads and storage facilities.

Conclusion:

- Agriculture remains a cornerstone of the Indian economy, providing food, employment, and raw materials.

- While it faces challenges, the sector's resilience and the government's support through various schemes and policies are crucial for its continued growth and contribution to the economy.

Findings of Agriculture Census 2015-16

- Operational Holdings: There was an increase in the number of operational holdings from 138.35 million in 2010-11 to 146.45 million in 2015-16, reflecting a growth of 5.86%.

- Operated Area: The total operated area decreased from 159.59 million hectares in 2010-11 to 157.82 million hectares in 2015-16, indicating a decline of 1.11%.

- Average Size: The average size of operational holdings dropped to 1.08 hectares in 2015-16, down from 1.15 hectares in 2010-11.

- Operational Holding is a crucial term used in various agricultural data contexts. It refers to agricultural land managed or operated by one person, either alone or with others, regardless of ownership title, size, or location.

- For instance, if a person owns land in four different locations and manages it, either personally or with the help of laborers, all that land is considered one operational holding. Similarly, if a person leases land from four different owners but manages the cultivation, it is still counted as one operational holding.

- The 11th Agriculture Census (2021-22) was initiated in July 2022.

A Brief History of Agriculture in India

Agriculture is a vital sector in the Indian economy, playing a crucial role in reducing poverty, generating employment, and contributing to the nation's GDP. Although agriculture's share of GDP has decreased from over 50% in 1950-51 to 16% in 2019-20, its importance remains significant. In 1950-51, agriculture accounted for 70% of employment, but this has now reduced to around 42%. Despite this decline, the growth of Indian agriculture is essential for 'inclusive growth.'

- A World Bank report highlights that GDP growth originating in agriculture is at least twice as effective in reducing poverty compared to GDP growth from other sectors.

- Between 1951 and 1966, food grain production increased at a rate of 2.8% per annum, which was insufficient to meet the rising consumption demand of a population growing at over 2% per annum. As a result, India began relying on food grain imports in the mid-1950s to feed its growing population. In 1956, India signed the Public Law (PL) 480 agreement with the United States to receive food aid, primarily in the form of wheat.

- Due to the wars with China in 1962 and Pakistan in 1965, India could not invest in rural development, and the consecutive droughts in 1965 and 1966 led to a severe food crisis. Food grain production and yield declined by 19% and 17%, respectively, in 1966. To prevent mass starvation, food grain imports were increased. During the Cold War, food aid was used as a political tool, and India experienced this when US shipments were temporarily halted during the drought. This prompted Indian leaders to recognize the political risks of relying on foreign sources for food security and to strive for self-sufficiency in food grain production.

Overview of the Green Revolution

- The Green Revolution signifies a transformation in agricultural methods that began in Mexico during the 1940s. This movement is credited to Norman Borlaug, an American scientist dedicated to improving agriculture. In the 1940s, Borlaug conducted research in Mexico, leading to the development of new, disease-resistant, high-yield varieties of wheat. Due to its success, the technologies associated with the Green Revolution spread globally in the 1950s and 1960s.

- The Green Revolution encompasses the introduction of High Yielding Variety (HYV) seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, improved irrigation, mechanization, and modern agricultural techniques. The core idea was to leverage technology to boost food production and adopt more Western-style farming practices. In India, M.S. Swaminathan is revered as the "Father of the Green Revolution."

Phases of the Green Revolution in India

- Phase I (1966-72): In 1966, India imported 18,000 tonnes of HYV wheat seeds, which were distributed in the irrigated regions of Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh.

- Phase II (1973-80): The technology of HYV was extended from wheat to rice, facilitated by the proliferation of tube wells, both private and government. This phase expanded the Green Revolution to eastern Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, coastal Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

- Phase III (1981-90): The Green Revolution reached the previously low-growth areas of West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, and Odisha during this phase.

Impact of the Green Revolution

The Green Revolution significantly increased food grain production in India, rising from 74 million tonnes (MT) in 1966-67 to 105 MT in 1971-72. By this time, India achieved self-sufficiency in food grains, reducing reliance on imports to nearly zero.

Current Agricultural Status

- As of 2022-23, horticulture production in India reached around 342 MT, while food grain production was 324 MT.

- India is the largest producer of milk and the second-largest producer of rice, wheat, sugarcane, and various fruits and vegetables.

- The country is also the largest exporter of rice and the second-largest exporter of beef and cotton.

- In the fiscal year 2021-22, India's agricultural exports amounted to $50 billion, while imports were $31 billion. This turnaround is remarkable, considering India relied on US imports for cereals in the mid-1960s.

Dr. Verghese Kurien and the White Revolution

- In 1949, Dr. Verghese Kurien, known as the "milkman of India," began his career in Anand, Gujarat. While working at a government creamery, he observed that poor and illiterate farmers were being exploited by milk distributors. Despite producing high-quality milk, these farmers were not paid fairly and were forbidden from selling directly to vendors.

- Inspired by Tribhuvandas Patel, a leader in the cooperative movement, Kurien and Patel started working on cooperative models to empower farmers in the Kheda district.

- This effort led to the establishment of "Amul" in 1949, officially known as the Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producer’s Union Ltd. (KDCMPUL). Initially, Amul had only two cooperative societies and a meager supply of 247 liters of milk.

- Amul's cooperative model gained popularity and caught the attention of the government. In 1964, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri visited Anand to inaugurate Amul's new cattle-feed plant. Impressed by the model's impact on improving farmers' economic conditions, he urged Dr. Kurien to replicate it nationwide.

- To facilitate this, the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) was established in 1965, with Dr. Kurien at the helm.

- During this time, milk demand was outpacing supply, and financing posed a significant challenge. In 1969, the NDDB secured a loan from the World Bank to launch Operation Flood, aiming to replicate the Anand model across India.

- The primary objectives of Operation Flood included: Increasing milk production (a "flood of milk"), Enhancing rural incomes, and Ensuring reasonable prices for consumers.

The Three-Tier Structure of the Operation Flood Business Model

Village Society

- At the village level, milk producers form a Village Dairy Cooperative Society (DCS).

- Any producer can join by buying a share and agreeing to sell milk exclusively to the society.

- Each DCS has a milk collection center where members deliver their milk daily.

- Milk is tested for quality, and payments are based on fat and SNF (Solid-Not-Fat) content.

- At the end of the year, a portion of the DCS profits is distributed as a patronage bonus to members, based on the quantity of milk they supplied.

The District Union

- A District Cooperative Milk Producers' Union is owned by the dairy cooperative societies in the district.

- The Union buys milk from these societies, processes it, and markets fluid milk and dairy products.

- Many Unions also provide essential inputs and services to DCSs, such as feed, veterinary care, and artificial insemination to enhance milk production and support the cooperatives' business.

- Union staff offer training and consulting services to help DCS leaders and staff.

The State Federation

- District Cooperative Milk Producers' Unions in a state form a State Federation, which is responsible for marketing the fluid milk and products of its member unions.

- Some federations also manufacture feed and assist with other union activities.

Process Overview

- Village Cooperative Society: Milk is collected from producers at the village level.

- District Milk Cooperative Union: Collected milk is processed at the district level.

- State Marketing Federation: Processed milk and products are marketed at the state level.

Achievements of the White Revolution

- Milk production in India grew from 20 million MT to 100 million MT in 40 years due to the dairy cooperative movement.

- India became the largest milk producer in the world, reaching 210 MT in 2020-21.

- The dairy cooperative movement expanded to over 125,000 villages across 180 Districts in 22 States.

Pink Revolution

Pink Revolution focuses on improving the meat and poultry processing sector in India through modernization, which involves specialization, mechanization, and standardization of processes. Technological upgrades and industrialization are essential for Indian entities to meet global standards, and developing mass production capabilities will enhance productivity.

Key Steps for Modernization

- Setting up advanced meat processing plants.

- Developing technologies for raising male buffalo calves for meat production.

- Increasing the number of farmers rearing buffalo under contractual farming.

- Establishing disease-free zones for animal rearing.

Current Status

- India has made significant progress in meat production, becoming the largest exporter of buffalo meat in 2012.

- Major importers of Indian meat include countries in the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Minimum Support Price (MSP)

Agriculture Crop Year: 1 July - 30 June

- Marketing Season of Kharif crops: Starts from 1st October

- Marketing Season of Rabi crops: Starts from 1st April

Before the sowing of each Rabi and Kharif crop season, the Government of India, through the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, announces the Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for procurement. This decision is based on the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) and requires the approval of the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA).

Legal Status of MSP:

- MSP currently lacks legal backing, meaning farmers cannot demand it as a legal right.

- It is an administrative decision by the government to purchase certain food grains at MSP.

- The government cannot compel private players to procure at MSP.

Role of CACP:

- The CACP, which is not a statutory body but an office within the Ministry of Agriculture, recommends MSP.

- The decision to fix or not fix MSP and its implementation lies with the government.

Factors Considered by CACP:

- Cost of Production: A2, A2+FL, and C2 costs

- Demand and Supply

- Price Trends: Domestic and international

- Inter Crop Price Parity

- Terms of Trade: Agriculture vs. non-agriculture products

- Impact on Consumers: Likely implications of MSP on consumers

Cost of Production:

- A2 Costs: Cover paid-out expenses like seeds, fertilizers, hired labour, etc.

- A2+FL Costs: Include A2 costs plus an imputed value for unpaid family labour.

- C2 Costs: Include A2+FL costs plus rentals and interest forgone on owned land and assets.

MSP Policy:

- The Finance Minister announced in the 2018-19 budget that MSP would be at least 50% over the cost of production (A2+FL).

- MSP is uniform across India for a particular crop.

Current MSP Recommendations:

CACP recommends MSPs for 23 commodities, including:

MSP of Minor Forest Produce (MFP)

The scheme titled "Mechanism for Marketing of Minor Forest Produce (MFP) through Minimum Support Price (MSP) and Development of Value Chain for MFP" falls under the Central government’s initiative and is managed by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

- Its primary goal is to ensure that MFP gatherers receive a fair price for their products, thereby improving their income levels and promoting sustainable harvesting practices.

- The Minimum Support Price (MSP) for Minor Forest Products is evaluated and revised every three years by the Pricing Cell within the Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

Implementation and Monitoring

- The Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development Federation of India (TRIFED) serves as the Central Nodal Agency for the scheme's implementation and monitoring.

- State-level implementing agencies carry out the scheme on the ground.

Procurement Process

- Designated State agencies are responsible for procuring notified MFPs directly from gatherers (individuals or collectives) when the market price falls below the MSP.

- Procurement is done at designated haats or procurement centers at the grassroots level, where gatherers are paid the MSP on the spot.

Financial Support

- The Central government provides financial assistance for procurement, infrastructure development, storage capacity, and processing units for MFPs, with a cost-sharing ratio of 75:25 between the Centre and the State.

Setting of MSP

- The MSP set by the Government of India serves as a reference point for fixing MSPs at the state level.

- State governments have the flexibility to set MSPs up to 10% higher or lower than the MSP declared by the Central government.

Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan (PM-AASHA)

In September 2018, the Union Cabinet approved the Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan (PM-AASHA), a new Umbrella Scheme aimed at ensuring remunerative prices for farmers' produce. This initiative reflects the government's commitment to supporting farmers (Annadata) and was announced in the Union Budget for 2019. PM-AASHA includes three sub-schemes:

- Price Support Scheme (PSS): Under PSS, the Central Nodal Agencies, with the active involvement of State governments, will physically procure pulses, oilseeds, and copra. In addition to the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) , the Food Corporation of India (FCI) will also undertake PSS operations in various states and districts. The Central Government will cover the procurement expenditure and any losses incurred during procurement as per established norms.

- Price Deficiency Payment Scheme (PDPS): PDPS aims to cover all oilseeds for which the Minimum Support Price (MSP) is notified. This scheme involves direct payment to pre-registered farmers, representing the difference between the MSP and the selling or modal price. Payments are made directly into the farmers' registered bank accounts. This scheme does not involve physical procurement, as farmers are compensated for the price difference when selling their produce in notified market yards. Central Government support for PDPS will be provided as per norms.

- Pilot of Private Procurement & Stockist Scheme (PPSS): Under PPSS, private agencies are authorized to procure commodities at MSP in notified markets during specified periods. This occurs when market prices fall below the notified MSP, and with the authorization of state or Union Territory governments. Private agencies may charge a maximum service fee of 15% of the notified MSP.

Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Scheme (PM-KISAN)

The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) scheme, which started on December 1, 2018, is a Central Sector initiative fully funded by the Government of India.

- Under this scheme, eligible farmer families receive an income support of ₹6,000 per year, disbursed in three instalments of ₹2,000 every four months.

- A "family" in this context is defined as the husband, wife, and minor children.

- The responsibility for identifying beneficiary farmer families lies with the State and Union Territory Governments.

- Certain groups, such as government employees, public sector undertakings (PSU) employees, and pensioners, are excluded from the scheme.

- Funds are transferred directly to the beneficiaries' bank accounts.

- To enroll in the scheme, farmers must approach local officials such as the patwari, revenue officer, or a Nodal Officer designated by the State Government.

- Common Service Centres (CSCs) are also authorized to register farmers for the scheme for a fee.

- While the PM-KISAN scheme may have some impact on inflation due to increased consumer spending, it is expected to be less inflationary than other schemes like Minimum Support Price (MSP) and input subsidies.

- Importantly, the scheme does not distort the market as it is not linked to the production of specific crops or agricultural output.

- This approach is seen as a way to alleviate farm distress while the government works on freeing agriculture markets and reducing the role of middlemen.

Agricultural Extension Services

Extension services, also known as rural advisory services, play a crucial role in enhancing agricultural productivity by offering timely guidance to farmers on best practices, technology adoption, contingency planning, and market information. Various agencies in India provide agricultural extension and advisory services.

- The Department of Agriculture and Cooperation (DAC), in collaboration with NABARD, has initiated a scheme to establish agri-clinics and agri-business centres/ventures run by agricultural graduates.

- The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) is also involved in agricultural extension activities through Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) and the Institute Village Linkage Programme (IVLP) across the country.

National Mission on Agricultural Extension & Technology (NMAET)

The National Mission on Agricultural Extension and Technology (NMAET), launched during the 12th Five-Year Plan, comprises four sub-missions aimed at improving agricultural extension and technology dissemination.

1. Sub-Mission on Agricultural Extension (SMAE):

- Focuses on increasing agricultural production and productivity through the adoption of quality seeds.

- Utilizes Agri Clinics, Agri Business Centres, and Kisan Call Centres to provide extension services to farmers.

2. Sub-Mission on Seed and Planting Material (SMSP):

- Covers the entire seed chain from nucleus seed production to supply to farmers for sowing.

- Aims to strengthen the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Authority (PPV&FRA) to protect plant varieties and promote the development of new plant varieties.

3. Sub-Mission on Agricultural Mechanization (SMAM):

- Emphasizes the importance of farm power availability for agricultural productivity.

- Focuses on farm mechanization, particularly for small and marginal farmers and regions with low farm power availability.

- Promotes institutional arrangements such as Custom Hiring Centres, mechanization of selected villages, and subsidies for machine and equipment procurement.

4. Sub-Mission on Plant Protection and Plant Quarantine (SMPP):

- Aims to increase agricultural production by preventing crop diseases using scientific and environmentally friendly techniques.

- Promotes Integrated Pest Management (IPM) to manage pests and diseases effectively.

- Custom Hiring Centres (CHCs) are units that provide expensive and advanced farm machinery, implements, and equipment for various agricultural tasks on a rental basis. These include equipment for tillage, sowing, planting, harvesting, threshing, plant protection, inter-cultivation, and residue management. CHCs are designed to help farmers who cannot afford to purchase high-end agricultural machinery and equipment.

- The government, through the Sub-Mission on Agricultural Mechanization (SMAM), is offering funds and subsidies to rural entrepreneurs, Self-Help Groups (SHGs), and others to establish CHCs. Under this scheme, the government provides a subsidy of 40% of the project cost to individual farmers, with a cap of Rs. 60 lakh, and 80% to groups of farmers for projects up to Rs. 10 lakh for setting up Custom Hiring Centres.

- National Mission on Agricultural Extension and Technology aims to restructure and strengthen agricultural extension to deliver appropriate technology and improved agronomic practices to farmers. It focuses on a mix of physical outreach, interactive information dissemination, use of ICT, popularization of modern technologies, capacity building, and promoting mechanization and quality inputs.

- The mission emphasizes the importance of agricultural extension and technology working together and aims to enhance farm mechanization, which is currently lower in India compared to countries like China and Brazil.

Introduction to Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs)

In India, the role of science and technology in agriculture is crucial not only for ensuring the country's food security but also for giving farmers a competitive advantage and keeping food prices affordable for the public. To realize their full potential, farmers need access to cutting-edge technologies, necessary inputs, and relevant information. In this context, the Government of India, through the Indian Council for Agricultural Research (ICAR), has established a vast network of over 700 Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) across the country. These KVKs aim to conduct technology assessment and refinement, disseminate knowledge, and provide critical input support to farmers with a multidisciplinary approach.

Role of KVKs in Agriculture

- On-Farm Testing and Demonstration: KVKs play a vital role in conducting on-farm testing to showcase location-specific agricultural technologies. They demonstrate the potential of various crops at farmers' fields to prove their effectiveness.

- Training Programs: KVKs organize need-based training programs for the benefit of farmers, farm women, and rural youth. These programs aim to enhance their skills and knowledge in modern agricultural practices.

- Awareness Campaigns: KVKs create awareness about improved agricultural technologies through a large number of extension programs. These initiatives help farmers stay informed about the latest advancements in agriculture.

- Input Production and Supply: KVKs produce and supply critical and quality inputs such as seeds, planting materials, organic products, bio-fertilizers, and livestock, piglet, and poultry strains to farmers.

Evolution and Impact of KVKs

- KVKs are evolving into grassroots institutions for empowering the farming community. They have become integral to decentralized planning and implementation to achieve desired growth levels in agriculture and allied sectors.

- The linking of 3.37 lakh common service centres (CSCs) with 721 KVKs has significantly enhanced the outreach of KVKs. This linkage provides demand-driven services and information to farmers, further strengthening the support system for the agricultural sector.

Farmers Producer Organization (FPO)

- Indian agriculture is primarily made up of marginal and small farmers who face significant challenges due to their scale, leading to uneconomic lot sizes for marketing and price risks. These small farmers also lack bargaining power in both input and output markets.

- To overcome these disadvantages, farmers can be organized under institutional mechanisms like Farmers Producers Organizations (FPOs).

- FPOs can take various forms such as companies, cooperative societies, or trusts, but the key is that they are legal entities that share profits and benefits among farmers.

- Ownership and control of FPOs rest with the members/farmers, and management is conducted by representatives of the members.

- The primary goal of an FPO is to ensure better income for farmers through collective organization.

- FPOs enable member farmers to benefit from economies of scale in input purchases, processing, and marketing of their produce. They also provide access to timely credit facilities and market linkages.

- Organizations like the Small Farmers Agribusiness Consortium (SFAC), National Co-operative Development Corporation (NCDC), and NABARD are instrumental in promoting and establishing FPOs.

- SFAC runs the Equity Grant Fund (EGF) Scheme, providing equity grants to FPOs to match shareholders' equity, up to ₹10 lakhs.

- To facilitate credit access for FPOs, NABARD and NCDC established a Credit Guarantee Fund (CGF). This fund minimizes financial institutions' risk in lending to FPOs, improving their financial capacity for better business plans and increased profits.

- NABARD offers collateral-free loans to FPO members for share capital contributions, up to ₹25,000 per member. It also provides credit support for FPOs' business operations and technical, managerial, and financial assistance for capacity building and market interventions.

- SFAC and NABARD provide training to FPO top management for effective functioning. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) supports FPOs with technical assistance through Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs).

- There are minimum member requirements to form an FPO, depending on its legal structure. Studies suggest that an FPO needs about 700 to 1000 active producer members for sustainable operation.

- Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) are groups formed by farmers to collectively manage and market their produce.

- They play a crucial role in bridging the gap between primary producers and the market by taking over various activities in the value chain.

Role of FPOs in Supporting Farmers

FPOs support farmers by:

- Reducing Costs: By aggregating demand for inputs and transporting in bulk, FPOs lower production costs.

- Enhancing Income: FPOs market produce in bulk for better prices and provide market information to help farmers sell at favorable times.

Activities Undertaken by FPOs

- Procurement of Inputs: Buying inputs in bulk to reduce costs.

- Disseminating Market Information: Providing farmers with market trends and price information.

- Facilitating Finance: Assisting farmers in obtaining finance for inputs.

- Aggregation and Storage: Collecting and storing produce from members.

- Primary Processing: Activities such as drying, cleaning, and grading produce.

- Brand Building and Marketing: Developing brands and marketing products to buyers.

- Quality Control: Ensuring produce meets quality standards.

Tax Exemption and Current Status

- Income from agricultural activities through FPOs is exempt from taxation.

- There are over 1000 registered FPOs in India, such as the Kashi Vishwanath Farmer Producer Company Limited in Varanasi.

Government Initiatives

- The Government of India has launched a scheme to form and promote 10,000 new FPOs with a budget of Rs 6865 crore.

Challenges in Agricultural Credit

- Despite government subsidies on agricultural credit, small and marginal farmers (86%) are not benefiting, leading to stagnant incomes.

- The government sets annual targets for agricultural credit, such as Rs 20 lakh crores for FY 2023-24, but the distribution and effectiveness of this credit remain questionable.

Institutional Credit Distribution in Agriculture

- A significant disparity exists in the distribution of subsidized institutional loans, with small and marginal farmers receiving only 15% of these loans, while big farmers receive 79%.

- As land holdings increase, the share of institutional credit also rises, but the majority of agriculture credit is being monopolized by big farmers and diverted to agricultural business companies.

- Despite an increase in agriculture credit, 95% of tractors and other agricultural equipment are being financed indirectly through Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs).

RBI Targets and Diversion of Credit

- The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has set a target of 18% of total credit to the agriculture sector, with 8% specifically for small and marginal farmers. However, these targets are being diverted and misallocated to big farmers and companies.

- This diversion indicates a misuse of agriculture credit for non-agriculture purposes.

Interest Rate Discrepancies

- One reason for the diversion is the refinancing of subsidized credit disbursed at 4% to 7% interest to small farmers and in open markets at rates as high as 36%.

Proposed Solutions

- Income Support : Instead of subsidized credit, provide income support to small and marginal farmers on a per hectare or per farmer basis. With the digitization of land records in many states, it would be easier for the government to implement this.

- Agricultural Credit through FPOs : Facilitate agricultural credit through Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) of small farmers to ensure that credit reaches the intended beneficiaries.

Marketing of Agricultural Produce

Agricultural markets in most parts of India are set up and regulated under the State APMC Acts. The entire geographical area of a state is divided into various market areas or mandis, each managed by a Market Committee appointed by the state government. Once an area is designated as a market area under the jurisdiction of a Market Committee, no individual or agency is allowed to conduct wholesale marketing activities outside this market.

The APMC Act stipulates that the first sale of agricultural commodities produced in the region, such as cereals, pulses, edible oilseeds, fruits, vegetables, and even livestock like chicken, goats, and sheep, as well as fish and sugar, can only be conducted through the APMC and licensed commission agents. Wholesalers, retail traders (such as Reliance Fresh), and food processing companies are not permitted to purchase farm produce directly from farmers. Instead, they must buy from these established mandis, and farmers are required to sell their produce in these markets.

Salient Features of APMC Act

- Licensing for Traders: Traders must obtain a license to operate in a Mandi, which requires them to have a shop or warehouse within the Mandi.

- Price Discovery: The prices for farmers' produce are determined through auctioning, ensuring that farmers receive a fair price for their goods.

Issues with the APMC Acts

- Wholesalers, retail traders, and food processing companies are prohibited from purchasing farm output directly from farmers. They must buy from established mandis, and farmers are required to sell their produce in these mandis.

- Different states impose varying mandi charges, leading to market distortions. These charges at the first level of trading significantly impact prices as the commodity moves through the supply chain.

- Mandis within a state are not integrated, resulting in high transaction costs for moving produce from one mandi to another. Separate licenses are needed for trading in different mandis within the same state.

How APMC Act has exploited the farmers and consumers

- Corruption in Licensing: Obtaining a license to operate in a mandi often involves bribery, leading to corruption and unethical practices.

- Price Manipulation: Auctioning of produce does not occur fairly. Even if it does, traders in the mandis form cartels that collectively suppress prices, harming farmers. During peak seasons, when traders buy from farmers at low prices, they do not reduce prices for final consumers. Conversely, during lean seasons, when consumer prices are high, traders do not pass on these price increases to farmers.

Electronic - National Agriculture Market (e-NAM)

The National Agricultural Market (NAM) is an online platform that enhances the existing system of physical markets, known as mandis. It is not a new marketing structure but aims to create a national network of these mandis that can be accessed online. NAM leverages the physical infrastructure of mandis by enabling online trading, allowing buyers from different states to participate in local trading.

Objectives of NAM:

- To create a unified national market for agricultural commodities by connecting selected APMC mandis through an electronic trading portal.

- To facilitate better price discovery for farmers by allowing them to access a larger pool of buyers.

- To improve the efficiency and transparency of agricultural marketing.

- To provide farmers with greater flexibility in selling their produce.

Implementation:

- NAM is implemented by the Small Farmers Agribusiness Consortium (SFAC), an autonomous organization under the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation (DAC).

- The initiative was launched in April 2016 with the aim of connecting all 2,500 APMC mandis across India.

How e-NAM Works:

- In e-NAM, traders from all over India can bid for farmers' produce. The highest bidder wins the right to purchase the produce, which may involve inter-state transactions.

- Farmers receive payment directly into their accounts before the physical produce is handed over to the trader.

- Transportation costs are the responsibility of the trader.

- To sell produce through e-NAM, farmers must bring their goods to an APMC mandi, a Farmers' Producer Organization (FPO) collection center, or a Warehouse Development and Regulatory Authority (WDRA) registered warehouse. These facilities are integrated with the e-NAM platform.

Future Developments:

- The government is exploring ways to enable farmers to sell their produce online from home using mobile devices, with physical produce remaining at home. However, this development may take a year or more to implement.

Key Features and Benefits of the National Agriculture Market (NAM)

- Increased Selling Options: Farmers have more choices when selling their produce. They can sell locally to traders in the physical mandi or reach out to traders in other states through the electronic platform.

- Standardized Procedures: As more mandis integrate into the NAM e-platform, there will be common procedures for licensing, fees, and produce movement, leading to increased competition and better price discovery.

- Enhanced Value Chains: NAM will promote the development of integrated value chains for major agricultural commodities, encouraging scientific storage and efficient movement of agricultural goods.

- Quality Standards: APMC mandis will ensure quality standards for agricultural goods sold through the e-platform. NAM aims to harmonize quality standards and provide quality testing infrastructure in every market to facilitate informed bidding by buyers.

- Integrated Logistics Services: e-NAM has integrated logistics services for transporting agricultural produce and is expanding to include various other services such as quality control, transportation, delivery, sorting, grading, packaging, insurance, trade finance, and warehousing.

Challenges Faced by the Electronic Portal

- Transitioning Traders: The primary challenge is encouraging traders who have been conducting transactions physically and in cash for a long time to shift to online methods.

- Quality Assurance: Ensuring the quality of produce is another hurdle, as farmers and traders may be located in different mandis or places. To address this, the government is establishing quality labs. When farmers bring their produce to the mandi, a quality certificate will be generated and uploaded online, allowing traders in different mandis to access it. However, traders still prefer to verify quality physically.

- Storage Capacity: There is a significant challenge regarding storage capacity in the mandis. Farmers need to bring their produce to the mandi, and it takes time for traders in other mandis to take this produce.

- Payment Process: Traders must make payment online before they are eligible to take the produce from the mandi.

- Slow Adoption: Since the e-NAM project was launched in April 2016, less than 5% of wholesale trade in farm commodities has moved online. Inter-mandi and inter-state e-NAM trade has not yet taken off.

[Model] Agri Produce and Livestock Marketing Act 2017

On April 25, 2017, the Central Government introduced a model law called the "Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion and Facilitation) Act 2017." This law aims to liberalize the trade in agricultural products and livestock, with the goal of doubling farmers' income by 2023. The new model law replaces an earlier one proposed by the Centre in 2003, which states were reluctant to adopt.

Key Features of the Model Act

- Promotion of Private Wholesale Markets: The law encourages the establishment of private wholesale markets, allowing farmers to sell directly to bulk buyers. This aims to enhance competition and improve farm gate prices for farmers.

- Direct Sales and Electronic Trading: Farmers will have the opportunity to sell their produce directly to bulk buyers, and the law promotes electronic trading platforms to facilitate these transactions.

- Expanded Regulated Markets: Godowns, warehouses, and cold storages will be recognized as regulated markets. Currently, there is one regulated market per 462 sq km, but the goal is to increase their availability to enhance selling options for farmers.

- Simplified Licensing and Fee Structure: The law proposes a single license and a single point of levy for market fees at the State level, with a gradual shift towards a national system. This aims to reduce disincentives for farmers and traders engaging in inter-State trade.

- Cap on Market Fees: The law sets a cap on market fees at 2% of the sale price for fruits and vegetables and 1% for food grains. This aims to reduce the financial burden on farmers.

- National Market for Agriculture Produce: The model Act promotes the creation of a national market for agricultural produce through inter-State trading licenses, grading and standardization, and quality certification.

- E-Trading and Transparency: The law encourages e-trading to increase transparency in agricultural markets and rationalizes market fee and commission charges.

- Special Commodity Market Yards: Provision for special commodity market yards to cater to specific needs and promote e-trading for enhanced transparency.

Impact/Benefit

- The Centre's decision to introduce a new model law that liberalizes the marketing of farm produce is a long-awaited step. This measure aims to provide farmers with better deals and ensure more stable prices for consumers regarding food items.

- Additionally, reducing both intra-State and inter-State barriers to the free movement of agricultural and livestock produce is crucial for transforming India into a unified common market.

- Comment: The success of the Act depends on the efficient adoption and implementation by State Governments, as it falls under their jurisdiction and is not mandatory for the States.

Contract Farming

Contract farming refers to agricultural production conducted based on an agreement between a buyer and farmers. This agreement outlines the terms for producing and marketing a farm product or products. Typically, the farmer commits to supplying specific quantities of a particular agricultural product that meet the buyer's quality standards and delivery timeline. In return, the buyer agrees to purchase the product and may provide support such as farm inputs, technical assistance, and land preparation.

- Advantages: Contract farming offers benefits to both farmers and purchasing firms. Farmers gain a guaranteed market outlet, reducing price uncertainty and often receiving loans in the form of farming inputs like seeds and fertilizers. On the other hand, purchasing firms secure a reliable supply of agricultural products that meet their quality, quantity, and delivery requirements.

- Issues: However, contract farming also comes with potential disadvantages and risks. If either party fails to uphold the terms of the contract, the affected party may suffer losses. Common issues include farmers selling to different buyers (side selling), companies refusing to buy at agreed prices, or downgrading produce quality. A frequent criticism of contract farming is the imbalance in the business relationship between farmers and buyers. Buying firms, often more powerful than farmers, may exploit their bargaining position for short-term gains, which could backfire in the long run as farmers might cease supplying them.

Current Trends in Contract Farming

- Despite some challenges, the overall balance of pros and cons for both firms and farmers in contract farming appears positive.

- Contractual arrangements are becoming increasingly common in agriculture worldwide.

Historical Context in India

- In 2003, the Central government proposed a Model Agricultural Produce and Marketing Committee (APMC) Act to the States, which included provisions for contract farming.

- This Act aimed to facilitate direct transactions between buyers and sellers without going through mandis (markets).

- However, contract farming has not gained the expected popularity or promotion in India, even in States that adopted this model.

Success Stories and Challenges

- There are notable success stories of contract farming in India, such as in the poultry sector, where it has thrived.

- However, in many other commodities, contract farming has either not taken off or has faced failures.

Roadblocks to Contract Farming

- Supply Side Constraints:

- The scale of farm produce is a significant constraint. Most Indian farmers are small and marginal, with 86% of land holdings being less than 2 hectares.

- The average farm size is less than one hectare in all states except Punjab.

- This results in a very small marketable surplus for individual farmers, making contract farming less attractive for buyers.

- High transaction costs, such as negotiation expenses, and marketing costs, like collecting produce, deter buyers from engaging in contract farming with numerous small farmers.

- There is also a problem of quality heterogeneity, as small farmers may not meet consistent quality and safety standards.

- To make contract farming successful, there is a need to consolidate farmers through Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) and Self-Help Groups (SHGs).

- Demand Side Constraints:

- The opening up of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in food retail in India was only in 2016, allowing big foreign retail chains like Amazon and Tesco to invest in the country.

- These retail chains have efficient supply chains and successful business models from other countries.

- Their entry into India is expected to bring technology and expertise, creating a demand for direct sourcing of farm produce from farmers.

Contract Farming Act 2018

In May 2018, the Government of India proposed the Model Agriculture Produce and Livestock Contract Farming and Services (Promotion & Facilitation) Act, 2018, encouraging states to implement it. This followed the Model Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2017, which did not address contract farming, leading to the need for a dedicated law on the subject.

Salient Features of the Model Contract Farming Act 2018

- Establishment of Authority: The Act proposes the creation of a neutral state-level agency called the “Contract Farming (Development and Promotion) Authority” to oversee and promote contract farming initiatives.

- Registration and Agreement Recording: A committee at the district or block level will be responsible for registering contract farming sponsors (buyers) and recording agreements to facilitate effective implementation.

- Rights and Ownership: The Act stipulates that no rights, title, ownership, or possession should be transferred or alienated to the contract farming sponsor.

- Production Support: It enables the provision of production support to farmers, including quality inputs, agronomic practices, technology, managerial skills, and necessary credit.

- Promotion of Farmer Producer Organizations: The Act encourages the formation of Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) and Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs) to help small and marginal farmers benefit from economies of scale.

- Guaranteed Buying: It ensures that the entire pre-agreed quantity of agricultural produce, livestock, or products will be bought as per the contract.

- Price Agreement Guidance: The Act provides guidelines for fixing pre-agreed prices and adjusting them in response to significant market price fluctuations.

- Contract Farming Facilitation Groups: These groups at the village or panchayat level will make timely decisions regarding production and post-production activities.

- Dispute Settlement Mechanism: A mechanism for quick dispute resolution at the local level for breaches of contract or violations of the Act’s provisions is included.

Introduction of Market Reforms

- The 1966 Green Revolution in agriculture is not regarded as "Market reforms" because it was heavily supported by government-led subsidies such as Minimum Support Price (MSP), fertilizers, electricity, and water. During this period, all inputs were provided at no cost, and the produce was purchased by the government at prices higher than the market rate (MSP). This was a government-led initiative rather than market reforms.

- However, government-led support is not sustainable in the long term, especially for a large country like India. It has become increasingly unfeasible for the government to maintain such extensive support in terms of MSP and subsidies. As a result, the government has introduced market-led reforms in agriculture through three acts, which are currently being protested by farmers in Punjab and Haryana.

Agriculture-Based Clusters

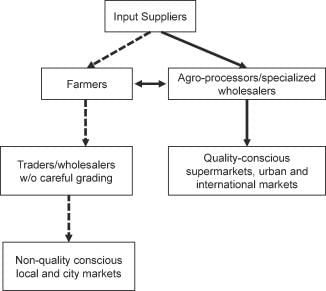

Agriculture in the 21st century is transforming into a global business influenced by factors like globalization, standardization, high-value production, increasing demand, and innovations in retail and packaging, along with improved efficiency. To remain competitive and innovative amidst constant productivity and market pressures, this "new agriculture" requires new tools, one of which is the promotion of agriculture-based clusters.

A cluster refers to the geographical concentration of industries that benefit from co-location. Agriculture Clusters (ACs) involve a concentration of producers, agro-industries, traders, and other private and public actors within the same industry, interconnected to address common challenges and pursue opportunities, either formally or informally.

The concept of agriculture clusters revolves around creating "value networks," which consist of:

- Horizontal relationships among producers, such as producer groups, self-help groups, or farmers' producers' organizations (FPOs).

- Vertical relationships involving suppliers of raw materials and production inputs, agricultural producers, processors, exporters, branded buyers, and retailers.

Agriculture Clusters offer several advantages to small producers and agribusiness firms, including agglomeration economies, improved access to local and global markets, and higher value-added production. By enhancing productivity and innovative capacity, ACs boost the competitive edge of farmers and agribusinesses.

Clusters foster "co-opetition," striking a balance between competition and cooperation. Agriculture Clusters are vital for the economic and social development of a region, positively impacting income, employment generation, and the well-being of workers and entrepreneurs within the cluster, thereby holding significant potential for local economic improvement.

Challenges for Agri Clusters

- Presence of a Large Number of Small and Marginal Farmers: Small and marginal farmers make up 86% of the agricultural workforce, posing challenges in terms of scale and resource allocation.

- Regulatory Hurdles: Issues such as Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) and land leasing regulations create obstacles for agricultural development and cluster formation.

- Meeting Consumer Demands: There is a need to balance consumer demands with increased efficiency and productivity in agricultural practices.

- Market-Driven Innovation and New Technologies: Introducing innovative and technology-driven solutions in response to market needs is essential for the growth of agri clusters.

- Stringent Environmental Regulations: Increasingly strict environmental regulations require compliance and adaptation within agri clusters.

Examples of Agro-Based Clusters

- Jute-Based Industries in West Bengal: Rural areas in West Bengal are known for jute-based industries, leveraging the abundant jute production in the region.

- Bamboo and Organic Food Processing in the Northeast: The Northeast region of India is developing processing facilities for bamboo and organic food, capitalizing on local resources and growing demand for organic products.

- Mega Food Parks: Initiatives in states like Punjab and Uttarakhand where Mega Food Parks connect farmers, suppliers, food processors, and retail chains, creating a cohesive agro-based cluster in a non-agricultural setting.

Agriculture Infrastructure Fund

The Agriculture Infrastructure Fund is a scheme launched by the Central Government to provide medium to long-term debt financing for investment in post-harvest management infrastructure and community farming assets. The scheme aims to support viable projects through interest subvention and financial assistance.

- Under this scheme, banks and financial institutions are expected to provide loans worth Rs. One Lakh Crore to various entities such as Primary Agricultural Credit Societies (PACS), Marketing Cooperative Societies, Farmer Producers Organizations (FPOs), Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), Self Help Groups (SHGs), Farmers, Joint Liability Groups (JLGs), Multipurpose Cooperative Societies, Agribusiness entrepreneurs, Start-ups, Aggregation Infrastructure Providers, and Public-Private Partnership projects sponsored by Central/State agencies or Local Bodies.

- The government offers an interest subvention of 3% per annum for loans up to Rs. 2 crore, applicable for a maximum period of seven years. Additionally, borrowers are eligible for credit guarantee coverage under the Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises (CGTMSE) scheme for loans up to Rs. 2 crore, with the fee for this coverage being paid by the government.

- The total budgetary support from the Government of India for subvention and guarantee is expected to be Rs. 10,736 crores. By facilitating formal credit to farm and farm processing-based activities, the scheme aims to create numerous job opportunities in rural areas. The duration of the Agriculture Infrastructure Fund scheme is from FY2020 to FY2033.

Benefits for Farmers and the Rural Economy

- Job Creation: The scheme aims to facilitate formal credit for farm and farm processing activities, which is expected to create numerous job opportunities in rural areas.

- Higher Prices for Farmers: Storage and processing facilities established through this fund will enable farmers to store their produce for a longer time, helping them secure higher prices for their crops.

- Reduced Wastage and Increased Value Addition: The infrastructure developed with this fund will contribute to reducing wastage and enhancing processing and value addition of agricultural products.

- Global Competitiveness: The scheme is designed to boost farmers and the agriculture sector, increasing India's competitiveness on the global stage.

- Investment Opportunities: India has significant opportunities to invest in post-harvest management solutions such as warehousing, cold chain, and food processing, which can help build a global presence in areas like organic and fortified foods.

Animal Husbandry Infrastructure Development Fund (AHIDF)

The Animal Husbandry Infrastructure Development Fund (AHIDF) aims to encourage investments in the establishment of dairy and meat processing and value addition infrastructure, as well as animal feed plants in the private sector.

Eligible Beneficiaries

- Farmers Producer Organizations (FPOs)

- Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)

- Not-for-Profit Companies

- Private Companies

- Individual Entrepreneurs

Funding Structure

- Beneficiaries are required to contribute a minimum of 10% as margin money for the project.

- The remaining 90% will be provided as a loan by scheduled banks.

Interest Subvention

- The Government of India will provide an interest subvention of 3% to eligible beneficiaries.

- Beneficiaries from aspirational districts will receive a higher subvention of 4%.

Loan Repayment Terms

- There will be a moratorium period of 2 years for the principal loan amount.

- The repayment period will be 6 years after the moratorium period.

Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY)

The Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) was launched in the Kharif season of 2016. Here are its key features:

- Uniform Premium Rates: There is a single premium rate for all food grains, oilseeds, and pulses within a season, eliminating variations across crops and districts. The rates are 2% for Kharif and 1.5% for Rabi crops. For horticulture and cotton, the premium may go up to 5%.

- Premium Sharing: Farmers pay a fixed premium, while the government (both Centre and States) covers the remaining cost.

- Full Insurance Coverage: Farmers receive full insurance coverage without any capping on the sum insured, ensuring that claim amounts are not reduced.

- Post-Harvest Loss Coverage: For the first time, post-harvest losses due to cyclones and unseasonal rains are covered nationally.

- Technology for Claim Assessment: The scheme emphasizes the use of mobile and satellite technology for accurate assessment and quick settlement of claims.

Coverage of Crops:

- Food crops (Cereals, Millets, and Pulses)

- Oilseeds

- Commercial/Horticultural crops

Coverage of Risks:

- Prevented Sowing/Planting Risk: Coverage for insured areas unable to sow or plant due to insufficient rainfall or adverse seasonal conditions.

- Standing Crop (Sowing to Harvesting): Comprehensive risk insurance for yield losses due to non-preventable risks such as drought, dry spells, flood, pests, diseases, and various natural disasters (e.g., storm, hailstorm, cyclone).

- Post-Harvest Losses: Coverage for post-harvest losses up to two weeks after harvesting for specific crops against risks like cyclone, cyclonic rains, and unseasonal rains.

- Localized Calamities: Coverage for loss or damage due to identified localized risks (e.g., hailstorm, landslide, inundation) affecting isolated farms in notified areas.

- Exclusions: Losses arising from war, nuclear risks, malicious damage, and other preventable risks are excluded from coverage.

- Optional Scheme: Participation in the scheme is optional for farmers.

Use of Technology for Crop Insurance

- Drone technology is rapidly advancing in the field of crop insurance. Drones are cost-effective, capable of flying at low altitudes, and can capture images in various resolutions necessary for assessing crop damage. They outperform satellites and remote sensing, particularly in avoiding cloud cover and providing higher frequency images.

- Additionally, low-cost satellites, known as "doves," can also aid in crop monitoring. These satellites offer good resolution, operate in low orbit, and can collect data from anywhere on Earth. The integration of these technologies will make monitoring and assessing crop damage significantly easier, faster, and more cost-effective.

Implementation of the Scheme

- Unit of Insurance: The State determines the 'Unit of Insurance' for a crop during a season. Typically, for major crops, this unit is set at the Village or Village Panchayat level. For minor crops, the unit may be set at a higher level to ensure sufficient crop cutting experiments can be conducted during the notified crop season.

- Threshold Yield: The Threshold Yield for a crop in an Insurance Unit is based on the average yield of the past seven years. Insurance protection is extended to all insured farmers in the unit based on this threshold. The sum insured for farmers is calculated as the Threshold Yield multiplied by the Minimum Support Price (MSP) or gate price of the insured crop.

- Selection of Insurance Companies: The State Government invites empanelled insurance companies to quote their premium rates for the notified crops in the specified insurance unit area. The company offering the lowest insurance premium is selected, with one company designated for each district.

- Damage Assessment: To assess crop damage or loss, the State conducts a requisite number of Crop Cutting Experiments (CCEs) at the level of the notified insurance unit for all notified crops. The yield data collected from these experiments is submitted to the insurance company within a month of harvest.

- Claims Processing: The insurance agency processes the claims liability assessed and approves the claims. The claim amount, along with relevant details, is released to individual Nodal Banks. These banks credit the claim amounts to the accounts of individual farmers and display the details of beneficiaries on their notice boards.

- Data Management: The banks provide individual farmer-wise claim credit details to the insurance agency, and this information is incorporated into a centralised data repository.

- Scheme Performance: The scheme is performing well, with coverage increasing to around 40% of farmers (approximately 5.5 crore farmers annually on average). However, there have been reports of issues such as delays in state premium subsidy payments, delays in claim settlements to farmers, and insurance companies making substantial profits.

Under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), the premium structure for crop insurance is as follows:

- If an insurance company charges a premium of 40%, farmers pay a fixed rate of 2% (applicable for kharif crops). The remaining 38% of the premium is shared equally between the Centre and the State, with each paying 19%.

- If the premium increases, farmers' contribution remains fixed at 2%, and the additional burden is shared equally by the Centre and the State.

However, in February 2020, the Central Government announced a modification to this arrangement. The Centre would adhere to the original formula only if the premium did not exceed 30%. If the premium exceeds 30%, for example, to 35%, the Centre's contribution would be capped at 14%, which is the amount it would pay if the premium were 30%. In this scenario, farmers would still pay 2%, but the State's responsibility would increase to cover the additional burden. Specifically, the State would pay 14% plus any amount exceeding 30%.

This 30% cap applies to unirrigated areas, while for irrigated areas, the cap is set at 25%.

Doubling Farmers' Income

The government aims to double farmers' real income by 2022-23, starting from the agricultural year 2015-16. However, it's important to note that an increase in agricultural output does not always lead to a proportional increase in farmers' income due to price factors.

Key Points:

- Farmers’ Welfare: Farmers’ welfare is more closely linked to their income, which is a product of output and price, rather than just agricultural output.

- Historical Focus: Historically, the political and bureaucratic focus has been on increasing tonnage rather than ensuring farmers benefit from it. This shift in focus led to the renaming of the Ministry of Agriculture to the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare in 2015.

- Need for Comprehensive Growth: Doubling farmers’ income requires harnessing all possible sources of growth, both within and outside the agriculture sector.

Sources of Growth within Agriculture:

- Crop Productivity: Most crops in India have low productivity, with significant scope for improvement. Except for wheat, other crops are below the world average and much lower than those in agriculturally advanced countries. There is also considerable variation in yields across states, primarily due to differences in irrigation access. Improving irrigation and technological advancements are crucial for enhancing agricultural productivity.

- Livestock Productivity: Livestock plays a vital role in farmers' economies, especially in mixed farming systems where the output of one enterprise becomes the input for another. The growth of this sector needs to keep pace with the rising demand reflected in changing food consumption patterns.

- Cropping Intensity: India has two main cropping seasons, kharif and rabi, which allow for the cultivation of two crops a year on the same land. With improved irrigation and new technologies, it is now possible to grow short-duration crops after the main kharif and rabi seasons. Currently, the second crop is grown on only 39% of net sown area, indicating that over 60% of agricultural land remains unused for half of the productive period. The lack of irrigation, with less than 50% of cultivable land under irrigation, is a significant barrier to increasing crop intensity.

1. Resource Use Efficiency

- Resource use efficiency or saving in cost of production is a key factor in improving farmers' income. It is closely related to Total Factor Productivity (TFP), which measures the growth in total output relative to the growth in total inputs used in production. When TFP improves, it indicates that more output is being produced with the same or fewer inputs, leading to cost savings.

- TFP growth is influenced by various factors such as technological change, skills, and infrastructure. When these factors improve, they contribute to higher TFP, resulting in increased farmers' income. For example, the adoption of new technologies, better farming practices, and improved infrastructure can all lead to higher TFP and, consequently, higher farmers' income.

2. Diversification towards High-Value Crops

- Diversification towards high-value crops (HVC) has the potential to significantly enhance farmers' income. Currently, staple crops such as cereals, pulses, and oilseeds occupy 77% of the gross cropped area but contribute only 41% of the total output in the crop sector. In contrast, high-value crops like fruits, vegetables, fiber, spices, and sugarcane occupy just 19% of the gross cropped area yet contribute nearly the same value of output as staple crops.

- This suggests that there is a disparity between the land dedicated to staple crops and the output they generate compared to high-value crops. By shifting focus and diversifying towards high-value crops, farmers can tap into a lucrative market and increase their overall income.

3. Improvement in Terms of Trade for Farmers

- Improvement in terms of trade for farmers is crucial for enhancing their real income. This involves adjusting farmers' current income with an appropriate inflation index. If inflation is higher than the prices received by farmers for their produce, it reduces their real income.

- Conversely, if the prices received by farmers rise faster than inflation, it increases their real income, even without a boost in output volume.

4. Shifting Cultivators from Farm to Non-Farm Occupations

- Shifting cultivators from farm to non-farm occupations can significantly improve farmers' income in India. Currently, around 43% of the labor force is engaged in agricultural activities, contributing only 17% to the GDP. This indicates an over-dependence on agriculture with substantial underemployment and a stark difference in per-worker productivity between the agriculture and non-agriculture sectors.

- By reallocating the workforce from agriculture to non-farm activities such as agro-processing, food processing, tourism, leather and footwear production, pottery, crafts, and handlooms, the income of farmers can be improved significantly. The available farm income will be distributed among a smaller workforce, leading to higher per capita income for those remaining in agriculture.

- The neglect of necessary reforms in the agriculture sector has created a wide disparity between agriculture and non-agriculture sectors. Until 1990-91, the growth rates in both sectors were closely correlated. However, with the progress of LPG (Liberalization, Privatization, and Globalization) reforms, the growth trajectories diverged. The non-agriculture sector experienced accelerated growth, while agriculture remained on a cyclical path around a long-term trend of 3% growth.

- This comparison highlights that without market reforms, agriculture growth remained low, and the sector could not keep pace with the growth in the non-agriculture sector.

|

Download the notes

Vivek Singh Summary Agriculture - 1

|

Download as PDF |

Agriculture Export Policy 2018

The Government has introduced a policy aimed at doubling farmers’ income by 2022, with agricultural exports playing a crucial role in this objective. To boost agricultural exports, the Government has formulated a comprehensive “Agriculture Export Policy” to double agricultural exports and integrate Indian farmers and products into global value chains.

The vision of the Agriculture Export Policy is to harness the export potential of Indian agriculture through appropriate policy instruments, making India a global agricultural power and increasing farmers’ income.

Objectives of the Agriculture Export Policy

- Doubling Agricultural Exports: Increase agricultural exports from over $30 billion (2017-18) to over $60 billion by 2022 and reach $100 billion in the subsequent years with a stable trade policy.

- Diversifying Export Basket: Diversify export products, destinations, and enhance high-value and value-added agricultural exports, with a focus on perishable goods.

- Promoting Novel and Traditional Products: Encourage exports of novel, indigenous, organic, ethnic, traditional, and non-traditional agricultural products.

- Institutional Mechanism: Establish an institutional framework to pursue market access, address barriers, and manage sanitary and phytosanitary issues.

- Increasing Global Share: Aim to double India’s share in global agricultural exports by integrating into the global value chain promptly.

- Empowering Farmers: Enable farmers to benefit from export opportunities in international markets.

Key Recommendations

1. Stable Trade Policy Regime

- There has been a tendency to utilize trade policy as an instrument to attain short-term goals of taming inflation, providing price support to farmers and protecting the domestic industry.

- Such circumstantial measures are often product and sector specific, for instance, the ad-hoc ban or imposition of minimum export prices (MEP) for onion and non-Basmati rice exports.

- India is seen as a source of high-quality agricultural products in many developing nations, ASEAN economies and changes in export regime on ground of domestic price fluctuations, religious and social belief can have long-term repercussions.

- It is imperative to frame a stable and predictable policy with limited State interference to send a positive signal to the international market.

- The policy aims to provide a policy assurance that the processed agricultural products and all kinds of organic products will not be brought under the ambit of any kind of export restriction.

2. Infrastructure and Logistics

- Presence of robust infrastructure remains a critical component of a strong agricultural value chain.

- Efficient and time-sensitive handling is extremely vital to agricultural commodities.

- Identifying strategically important clusters, creating inland transportation links alongside dedicated agri infrastructure at ports with 24x7 customs clearance for perishables will therefore go a long way in boosting trade exponentially.

- Expenses towards logistics handling in India are about 14 to 15% of the cost of exports.

- Benchmarked against 8 to 9% in some of the developed economies, the savings on account of improved logistics can make Indian agricultural exports significantly competitive in the global market place.

3. Cluster Development

- Cluster development is crucial for exporting horticultural products, which require large volumes of high-quality produce of the same variety with standardized parameters. Due to India's small landholding pattern and low farmer awareness, there is often a limited supply of different varieties of multiple crops with little or no standardization.

- To meet export demands, it is essential to develop export-oriented clusters across states that can ensure surplus produce with consistent physical and quality parameters.

4. Promoting Value-Added Exports

- India's export basket is primarily composed of products with little or no processing or value addition.

- There is a significant demand for processed products in the global market, and India has the potential to export a wide range of value-added fruits and vegetables, ready-to-eat products, pickles, soups and sauces, dairy products, processed livestock, aquaculture products, and textile products.

5. Ease of Doing Business

- Exporters across sectors have consistently demanded a dedicated platform to access trade and market-related information. Currently, relevant information on market intelligence is scattered across different web pages, making it difficult for exporters to make well-informed decisions.

- To address this issue, there is a need to develop an integrated online portal that provides real-time updates on tariff, non-tariff, documentation, pesticide and chemical MRL notifications. This portal will facilitate exporters in making informed decisions related to markets, pricing, hedging, and SPS notifications.

- Exporters face ongoing challenges due to the lengthy and complicated documentation and operational procedures at ports. To address this, they have consistently recommended the implementation of 24 x 7 single window clearance for perishable imports and exports at key ports across the country. Additionally, it is crucial to increase the number of quarantine officers at strategically important ports.

6. SPS and TBT (Technical Barriers to Trade) Response Mechanism:

- Issues related to market access often take a long time, sometimes months or even years, before countries grant permission for products to enter their markets. While tariff barriers have been decreasing over the years due to Free Trade Agreements and Regional Trade Agreements, Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) and stringent quality/phyto-sanitary standards are becoming more common as a means to restrict or prevent market access.

- It is essential to respond quickly to alerts and warnings regarding these barriers and ensure that any concerns or problem areas are communicated to producers, processors, and exporters. Without an effective response mechanism, the risk of temporary restrictions or bans increases, and it can take a long time to lift such bans. For example, bans on fruits and vegetables to the EU and on green chilies to Saudi Arabia have occurred in the past.

7. Developing Sea Protocol:

- Developing Sea protocols for perishables should be prioritized for long-distance markets. Exporting perishables requires special storage, transportation, and handling at specific temperatures. Since time is a critical factor and air freight is expensive for exporters, establishing sea protocols for various exportable commodities can significantly boost India’s fresh produce exports.

- A sea protocol would outline the optimal maturity level for harvesting produce intended for sea transportation. This initiative needs to be undertaken in collaboration with shipping lines, reefer service providers, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, and the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA).

- Countries like the Philippines and Ecuador have successfully developed sea protocols for exporting bananas, allowing for 40 and 24 days of sea transport, respectively. For instance, the Philippines exports bananas to the Middle East, which takes around 18 days, while India currently manages to ship produce within a 2-4 day transit period. Therefore, developing a sea protocol can significantly enhance trade opportunities for India.

8. Conformity Assessment:

- Many importing countries do not recognize India’s export inspection and control processes. This lack of recognition for Indian testing procedures and conformity standards can be costly for exporters and, consequently, for farmers. Often,

- Various laboratories across the country are conducting multiple and duplicate tests, leading to increased testing for products like spices, organic food, and Basmati rice. The government needs to focus on mutual recognition of ethnic and organic products and standards during bilateral discussions to address this issue.

Comparison of Indian and Chinese Agriculture (2018-19)

In 2018-19, India had 158 million hectares of agricultural land compared to 120 million hectares in China. India also had a higher percentage of irrigation cover at 48%, while China had 41%.

- In terms of agriculture output, India produced $407 billion (17% of GDP) whereas China produced $1,367 billion (8% of GDP).

- Regarding expenditure on agriculture research and development (R&D) and extension, India spent $1.4 billion while China spent $7.8 billion.

- In terms of fertilizer consumption, India used 166 kg/ha compared to China’s 503 kg/ha. The labor force in agriculture constituted 43% of India’s workforce, while in China it was 26%.

- Both countries have embraced modern agricultural technologies since the mid-1960s, including high-yield variety (HYV) seeds, expanded irrigation, and increased chemical fertilizer usage to enhance food production from limited land.

Agricultural Policies

- China initially implemented support price schemes for farmers, leading to large stockpiles and significant expenditure. However, it later reduced support prices for corn, wheat, and rice. In contrast, India has continued to raise procurement prices under the Minimum Support Price (MSP) scheme.

Input Subsidies

- China streamlined its input subsidies into a single scheme, providing direct payments to farmers based on per hectare criteria. This approach, which cost $20.7 billion in 2018-19, allows farmers to choose their crops freely and encourages optimal resource use. Conversely, India spent only $3 billion on its direct income scheme, PM-KISAN, while allocating $27 billion on subsidizing fertilizers, power, irrigation, insurance, and credit. This disparity has led to inefficiencies and environmental concerns in resource usage.

Recommendations for India

- It may be beneficial for India to consolidate its input subsidies and provide direct payments to farmers on a per hectare basis, similar to China’s approach. Additionally, freeing up prices from controls could enhance efficiency and productivity in Indian agriculture.

Productivity Levels