Overview: Indian Evidence Act, 1872 | Legal Reasoning for CLAT PDF Download

Introduction

The Indian Evidence Act, 1872, is a law that helps courts decide what information (evidence) can be used in trials. It applies to both civil (like property disputes) and criminal cases (like theft or murder), but it’s super important in criminal trials. Below is an easy-to-understand guide to its key topics.

Relevance and Admissibility (Sections 1–55)

This part explains what kind of evidence courts can look at.

- Facts in Issue: These are the main facts the court needs to decide. For example, in a theft case, whether the accused stole something is a fact in issue.

- Relevant Facts: These are facts connected to the case that help explain what happened. For example, if someone saw the accused near the crime scene, that’s a relevant fact.

- Admissibility: Not all facts can be used in court. The Act says only relevant facts that follow its rules can be admitted as evidence.

Admissions (Sections 17–23)

An admission is when someone says something that supports the other side’s case.

- For example, if a person admits in court they owe money, that’s an admission.

- Admissions can be made by the accused, their lawyer, or someone involved in the case.

- They must be clear and voluntary to be used as evidence.

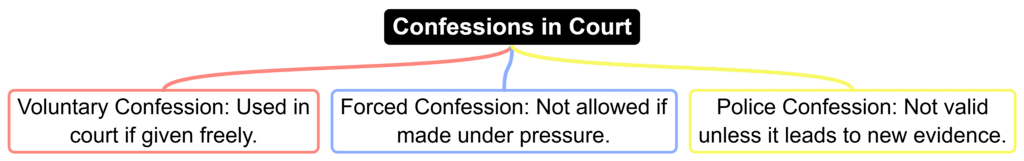

Confessions (Sections 24–30)

A confession is when the accused admits they committed the crime.

Dying Declarations (Section 32)

A dying declaration is a statement made by a person who is about to die, explaining how they were hurt or killed.

- For example, if a victim says, “Ravi stabbed me” before dying, that statement can be used in court.

- It’s trusted because people are unlikely to lie when they know they’re dying.

- The person doesn’t need to die for the statement to be used, but they must believe they’re in danger of dying.

Expert Opinion (Section 45)

Sometimes, courts need help from experts to understand complex things.

- For example, a doctor might explain a medical report, or a handwriting expert might check if a signature is real.

- Experts give their opinions on things like science, art, or technical stuff.

- The court decides how much weight to give to the expert’s opinion.

Character Evidence

This is about using someone’s character (good or bad) as evidence.

- In criminal cases, the accused’s good character can help show they’re unlikely to commit a crime.

- Bad character evidence is usually not allowed unless it’s directly related to the case.

- For example, if someone is accused of theft, their past thefts might be relevant, but not their unrelated habits.

The Indian Evidence Act makes sure trials are fair by setting clear rules for what evidence can be used. It protects people from unfair evidence (like forced confessions) and helps judges make decisions based on facts. It’s especially critical in criminal cases, where someone’s freedom or life might be at stake.

Proof of Facts (Sec 56–100)

This part explains how facts are proven in court so the judge can make a fair decision.

- Facts That Don’t Need Proof: Some facts are so obvious (like the sun rises in the east) that the court accepts them without evidence (Section 56).

- Facts Admitted by Parties: If both sides in a case agree on a fact, it doesn’t need to be proven (Section 58).

- How Evidence Is Given: Evidence can be oral (spoken) or documentary (written), and this section sets rules for both (explained below).

Oral & Documentary Evidence

Evidence comes in two main forms: what people say and what’s written down.

- Oral Evidence (Sections 59–60): This is when witnesses speak in court about what they saw or know. It must be direct (e.g., “I saw him steal”) and not hearsay (e.g., “Someone told me he stole”).

- Documentary Evidence (Sections 61–90): This includes things like letters, contracts, or photos. Documents must be authentic, and the court checks if they’re original or valid copies.

- Primary vs. Secondary Evidence: Original documents (primary) are preferred, but copies (secondary) can be used in some cases, like if the original is lost.

Presumptions

Presumptions are things the court assumes to be true unless proven otherwise.

- Example: If a person has been missing for 7 years, the court may presume they’re dead (Section 108).

- Types of Presumptions: Some are “may presume” (court can assume but can be challenged) or “shall presume” (court must assume unless disproved).

- Presumptions help speed up cases by not requiring proof for obvious or likely facts.

Burden of Proof (Sections 101–114)

This explains who needs to prove what in a trial.

This explains who needs to prove what in a trial.

- General Rule: The person who makes a claim must prove it. For example, in a theft case, the prosecution must prove the accused stole something (Section 101).

- Shifting Burden: Sometimes, the burden shifts. If the accused claims they were insane during the crime, they must prove it (Section 105).

- Special Cases: In some situations, like dowry death cases, the law assumes the accused is guilty unless they prove otherwise (Section 113B).

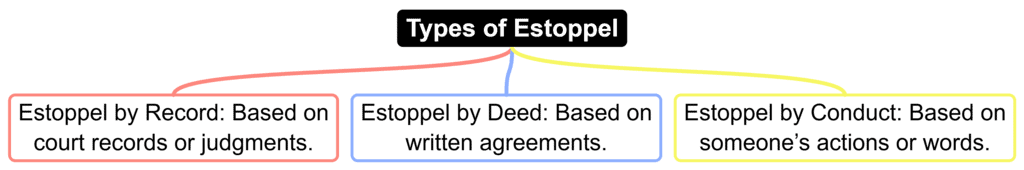

Estoppel (Sections 115–117)

Estoppel is a rule that stops someone from denying something they previously said or did if it affects another person.

- Example: If you tell someone they can use your land and they build a house on it, you can’t later say it’s not their land (Section 115).

- It ensures fairness by preventing people from changing their story to harm others.

The Indian Evidence Act’s rules on proving facts make sure trials are fair and based on clear evidence. They decide who has to prove what, how evidence is presented, and when the court can assume certain things. This is especially crucial in criminal cases, where someone’s freedom or life depends on the evidence.

Witnesses and Evidence Guide(Sec 118–167)

The Indian Evidence Act, 1872, sets rules for how witnesses give evidence in court, whether in civil cases (like property disputes) or criminal cases (like theft or murder).

Competency of Witnesses (Sections 118–120)

This part explains who is allowed to be a witness in court.

- General Rule: Almost anyone can be a witness if they understand the questions and can give clear answers (Section 118).

- Children: A child can testify if they understand what’s being asked and can answer sensibly, even if they’re young.

- People with Mental Disabilities: They can be witnesses if they can understand and answer questions properly.

- Exceptions: People who can’t communicate (like someone in a coma) or don’t understand the duty to tell the truth may not be allowed.

Privileged Communications (Sections 121–129)

Some conversations are private and can’t be shared in court, even if they’re relevant.

- Husband and Wife: Spouses can’t be forced to share private conversations they had during their marriage (Section 122).

- Lawyers and Clients: A lawyer can’t reveal what their client told them unless the client agrees (Section 126).

- Government Secrets: Information that could harm the country (like national security) can be kept secret (Section 123).

- Exception: If a conversation involves a crime, like planning a robbery, it’s not protected.

Examination of Witnesses (Sections 135–166)

This explains how witnesses are questioned in court to get their evidence.

- Examination-in-Chief: The lawyer who calls the witness asks questions first to get their side of the story.

- Cross-Examination: The other side’s lawyer asks questions to test the witness’s story or find weaknesses.

- Re-Examination: The first lawyer can ask more questions to clear up anything confusing from the cross-examination.

- Rules: Questions must be relevant, and witnesses can’t be harassed or asked improper questions (Section 151).

Hostile Witnesses (Section 154)

Sometimes, a witness doesn’t support the side that called them to court.

- What’s a Hostile Witness? If a witness gives answers that harm the case of the person who called them, they’re called “hostile.”

- What Happens? The lawyer can ask the court’s permission to treat them as hostile and ask tougher questions, like in cross-examination.

- Example: If a witness was supposed to say they saw the accused steal but says the opposite, they might be declared hostile.

Refreshing Memory (Section 159–161)

Witnesses can use certain things to help remember details while testifying.

- How It Works: A witness can look at notes, documents, or records they made earlier (like a diary or report) to jog their memory (Section 159).

- Rules: The document must have been made when the events were fresh in their mind, and the other side can see it.

- Example: A police officer might use their notebook to recall the exact time of a crime.

- Special Case: If a witness can’t remember even with notes, the document itself might be used as evidence (Section 160).

The rules on witnesses and evidence in the Indian Evidence Act make sure trials are fair. They decide who can testify, protect private conversations, and ensure witnesses are questioned properly. This is especially crucial in criminal cases, where the evidence given by witnesses can decide someone’s fate.

Documentary Evidence (Sec 61- 90)

Documentary evidence includes anything written or recorded, like letters, contracts, photos, or digital files, used to prove facts in court.

Primary and Secondary Evidence

- Primary Evidence (Section 62): This is the original document itself, like an original signed contract. It’s the best evidence because it’s the most reliable.

- Secondary Evidence (Section 63):These are copies or other versions of the original, like a photocopy or a scanned image. Secondary evidence can be used if:

- The original is lost or destroyed.

- The original is with the other party and they won’t share it.

- The court allows it for other valid reasons.

- Rule: Courts prefer primary evidence, but secondary evidence is okay if the original isn’t available (Sections 64–65).

Public and Private Documents

- Public Documents (Section 74): These are official records made by government or public authorities, like birth certificates, court judgments, or land records. They’re trusted and easier to use as evidence.

- Private Documents (Section 75): These are documents created by individuals or companies, like personal letters or private contracts. They need more proof to show they’re genuine.

- How They’re Proved: Public documents can be proved with certified copies, while private documents often need the original or a witness to confirm they’re real (Sections 76–78).

Electronic Evidence (Section 65B)

- What Is It? Electronic evidence includes digital files like emails, text messages, videos, or computer records.

- Rules for Use: To use electronic evidence in court, you need a certificate (under Section 65B) that confirms the file is genuine and was obtained properly (e.g., from a computer or phone).

- Example: A WhatsApp chat can be used as evidence if it’s submitted with a certificate verifying its authenticity.

- Why It Matters: With more digital evidence in cases today, Section 65B ensures it’s reliable.

Key Court Cases

These famous cases help explain how the Evidence Act is used in real life.

Pakala Narayana Swami v. Emperor (1939)

- What Happened? This case was about a murder, and the court looked at what counts as a confession.

- Key Point: The court said a confession is any statement by the accused that suggests they’re guilty, even if it’s not a full admission. For example, saying “I was at the crime scene” could be a confession if it links them to the crime.

- Impact: This case widened the scope of confessions under Sections 24–30, helping courts decide what statements can be used as evidence.

State of UP v. Raj Narain (1975)

- What Happened? This case was about whether certain government documents could be kept secret in court.

- Key Point: The court ruled that privileged communications (like government secrets) can be protected under Section 123, but only if they truly harm public interest. Courts can check the documents to decide.

- Impact: This case balanced government secrecy with the public’s right to a fair trial, clarifying rules for privileged communications.

Anvar P.V. v. P.K. Basheer (2014)

- What Happened? This case dealt with whether a CD containing election-related data could be used as evidence.

- Key Point: The Supreme Court said electronic evidence (like CDs, emails, or videos) is only admissible if it comes with a certificate under Section 65B to prove it’s authentic.

- Impact: This case made Section 65B’s certificate rule strict, ensuring digital evidence is reliable in court.

Conclusion

The Indian Evidence Act, 1872, is a key law that guides how evidence is used in Indian courts for both criminal and civil cases. It sets clear rules for what evidence counts, like spoken words, documents, or digital records, and explains who has to prove what. It ensures trials are fair by following standards like proving guilt "beyond reasonable doubt" in criminal cases or "more likely than not" in civil cases. In conclusion, the Act is a vital part of India’s justice system, making sure evidence is handled properly, trials are fair, and the truth is found, while keeping up with modern needs like electronic evidence.

|

63 videos|174 docs|38 tests

|

FAQs on Overview: Indian Evidence Act, 1872 - Legal Reasoning for CLAT

| 1. What is the significance of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 in the judiciary system? |  |

| 2. How does the Indian Evidence Act differentiate between relevant and admissible evidence? |  |

| 3. What are the key provisions related to documentary evidence in the Indian Evidence Act? |  |

| 4. Can you explain the role of witnesses in the context of the Indian Evidence Act? |  |

| 5. What are some landmark court cases that have interpreted the provisions of the Indian Evidence Act? |  |