General Defences of Tort | Legal Reasoning for CLAT PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| General Defences in Tort Law |

|

| What Are General Defences? |

|

| Key General Defences |

|

| Conclusion |

|

General Defences in Tort Law

Tort law addresses civil wrongs where one party causes harm to another, leading to legal liability. Defendants can use general defences to avoid or reduce liability by proving circumstances that justify, excuse, or mitigate their actions. These defences are crucial for CLAT UG aspirants, as they frequently appear in legal reasoning questions. This section explains each general defence in clear, accessible language, with examples, Indian case law, and additional details to aid understanding.

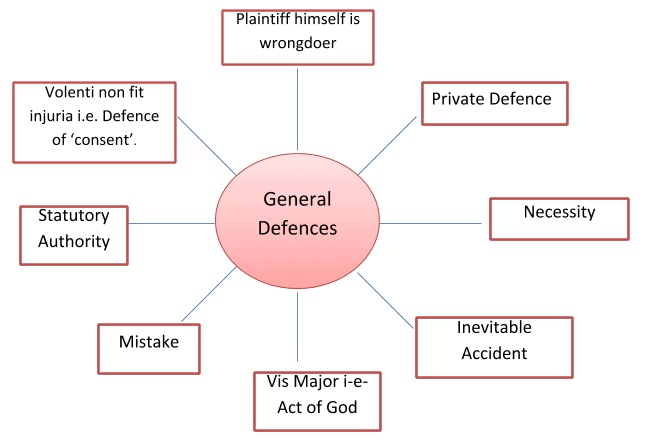

What Are General Defences?

General defences are legal arguments a defendant uses to avoid tort liability. They demonstrate that the defendant’s actions were not wrongful, were unavoidable, or were not solely their fault. These defences shift the focus from the plaintiff’s harm to the defendant’s justification or circumstances, often requiring the defendant to prove their applicability.

Key General Defences

Below are the primary general defences in tort law, enhanced with explanations, examples, and Indian case law for CLAT preparation.

1. Volenti Non Fit Injuria (Consent)

If a person willingly agrees to risk harm and gets injured, they cannot sue for damages. The Latin maxim Volenti Non Fit Injuria means “no injury is done to a willing person.” By freely consenting to a risk, the plaintiff waives their right to claim compensation.

Key Requirements:

- Knowledge of Risk: The plaintiff must be aware of the potential harm.

- Free Consent: The plaintiff must voluntarily agree to the risk, without coercion, fraud, or misrepresentation.

Examples:

- Inviting a friend to your home prevents suing them for trespass, as you consented to their entry.

- A cricket player hit by a ball during a match cannot sue, having accepted the game’s risks (Hall v. Brooklands Auto Racing Club, 1933).

Indian Case Law:

- South Indian Industrial Ltd. v. Alamelu Ammal (1923): A factory worker who voluntarily undertook a risky task could not claim damages for injuries, as they knowingly accepted the risk.

- Bowater v. Rowley Regis Corp. (1944) (applied in India): A worker who agreed to drive a defective vehicle could not sue, as consent was informed.

Exception - Rescue Cases:

- The defence does not apply if someone risks harm to rescue another from danger caused by the defendant’s negligence, as the rescuer acts out of moral or legal duty.

- Example: Haynes v. Harwood (1935): A policeman injured while stopping a runaway horse caused by the defendant’s negligence recovered damages, as his act was a rescue.

- Indian Context: State of Rajasthan v. Vidyawati (1962): A pedestrian injured while rescuing someone from a government vehicle’s negligent driving could claim damages, as the rescue was necessitated by the defendant’s fault.

Explanation: The defence distinguishes knowledge (awareness of risk) from consent (willing acceptance). Consent obtained through coercion or fraud is invalid.

2. Inevitable Accident

An inevitable accident is an unexpected event causing harm despite the defendant’s reasonable care. If the harm could not have been foreseen or prevented, the defendant is not liable.

Key Requirements:

- The event must be unforeseeable.

- The defendant must have exercised reasonable care.

Example:

- Stanley v. Powell (1891): During a pheasant hunt, a defendant’s shot ricocheted off a tree, injuring the plaintiff. The court ruled it was an inevitable accident, as the defendant acted carefully.

Indian Case Law:

- Nitin Walia v. Union of India (2001): A train derailment due to a sudden, unforeseeable mechanical failure, despite regular maintenance, was an inevitable accident, absolving the railway authority.

Explanation: Unlike negligence, where the defendant fails to take care, inevitable accident requires proof that the defendant did everything possible to prevent harm. It highlights the absence of fault.

3. Act of God (Vis Major)

Act of god is a good defence to any action in tort. Thus, when the damage, loss or injury is caused on account of operation of natural forces or phenomena, such as heavy downpour, storms, floods, earthquakes droughts etc, the defendant can escape liability.

Key Requirements:

- The harm must result from natural forces without human intervention.

- The event must be extraordinary and unforeseeable.

Example:

- Nichols v. Marsland (1876): A dam burst due to unprecedented rainfall, flooding the plaintiff’s property. The defendant was not liable, as the flood was an Act of God.

Indian Case Law:

- Ramalinga Nadar v. Narayana Reddiar (1971): Damage caused by a cyclone was ruled an Act of God, being beyond control.

Explanation: The defence fails if negligence contributes to the harm (e.g., poor dam maintenance). Courts emphasize the event’s exceptional nature, distinguishing it from routine weather conditions.

4. Plaintiff the Wrongdoer (Ex Turpi Causa Non Oritur Actio)

Under the law of contract, one of the principles is that no court will aid a person who forward his cause of action upon an immoral or an illegal act. The maxim is “Ex turpi causa non oritur actio” which means, from an immoral cause no action arises. It means that if the basis of the action of the plaintiff is an unlawful contract, he will not in general, succeed to his action.

Key Requirements:

- The plaintiff’s wrongful act must be the primary cause of harm.

- The act must be illegal or immoral (e.g., breaching a legal duty).

Example:

- A truck driver overloading their vehicle against a bridge’s weight limit, causing collapse, cannot sue, as their illegality caused the harm.

Indian Case Law:

- Asaram B. Thakore v. Laxmi Dyeing Works (1982): A plaintiff transporting illegal goods could not claim damages for losses from their unlawful act.

Explanation: Related to contributory negligence (where fault reduces damages), this defence bars recovery entirely if the plaintiff’s illegality is central. If the defendant’s negligence dominates, recovery is possible (Davies v. Mann, 1842).

5. Necessity

An intentional act causing harm is not actionable if done to prevent a greater harm. The defence applies when the defendant acts to protect life, property, or public interest.

Key Requirements:

- The act must be necessary to avoid greater harm.

- The harm caused must be proportionate to the harm prevented.

Examples:

- Forcibly feeding a hunger-striking prisoner to save their life is justified.

- Entering a property to extinguish a fire already managed by firefighters is trespass if unnecessary (Cope v. Sharpe, 1912).

Indian Case Law:

- State of U.P. v. Hari Ram (1983): Demolition of an unsafe building to prevent public harm was necessary, excusing liability.

Explanation: Courts evaluate whether the action was reasonable and if less harmful alternatives existed. Excessive or unnecessary acts void the defence.

6. Statutory Authority

Acts authorized by legislation are not actionable, even if they cause harm, if the defendant complies with the statute. This protects legally mandated actions.

Key Requirements:

- The act must be expressly or impliedly authorized by a statute.

- The defendant must act without negligence within the statute’s scope.

Types:

- Absolute Authority: Complete immunity, regardless of negligence (rare).

- Conditional Authority: Immunity if reasonable care is exercised.

Example:

- Vaughan v. Taff Vale Railway Co. (1860): Sparks from a statutorily authorized railway engine caused a fire. The railway was not liable, having taken care.

Indian Case Law:

- Kasturi Lal v. State of U.P. (1965): The state was not liable for damage from a statutorily authorized act performed without negligence.

Explanation: Negligence or deviation from the statute voids immunity. The defence ensures compliance with legal mandates.

7. Contributory Negligence

Contributory negligence occurs when the plaintiff’s own negligence contributes to their harm, leading to a reduction in damages based on their share of fault. This defence apportions liability rather than absolving the defendant entirely.

Key Requirements:

The plaintiff’s negligence must contribute to the harm suffered.

The harm must result from the combined negligence of both plaintiff and defendant.

Types:

Partial Contribution: Damages are reduced proportionate to the plaintiff’s fault.

Significant Contribution: If the plaintiff’s negligence is predominant, recovery may be minimal.

Example:

Butterfield v. Forrester (1809): A plaintiff who rode carelessly into an obstruction left by the defendant was partly liable, reducing damages due to their own negligence.

Indian Case Law:

Municipal Corporation of Delhi v. Subhagwanti (1966): A pedestrian’s careless road-crossing contributed to their injury, reducing the defendant’s liability for damages.

Explanation: Unlike the Plaintiff the Wrongdoer defence, which bars recovery due to illegal acts, contributory negligence apportions damages based on fault, as recognized under the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act, 1945, applied in India. The plaintiff may need to disprove their negligence to maximize recovery.

8. Private Defence

Private defence justifies harm caused to protect oneself, property, or others from imminent danger, provided the response is reasonable and proportionate. This defence prioritizes self-preservation within legal limits.

Key Requirements:

There must be an imminent threat to person or property.

The defensive act must be proportionate and necessary to avert the threat.

Types:

Defence of Person: Protecting oneself or others from physical harm.

Defence of Property: Safeguarding property from theft or damage.

Example:

Morris v. Nugent (1836): A defendant who shot a dog attacking their livestock was not liable, as the act was necessary to protect property.

Indian Case Law:

Ram Rattan v. State of U.P. (1977): A defendant who injured an aggressor in self-defence was not liable, as the force used was proportionate to the threat.

Explanation: The defence fails if the force is excessive or the threat is not immediate. Courts balance the right to self-defence with the need to avoid unnecessary harm.

9. Mistake

Mistake of fact (not law) may excuse liability in limited tort cases, such as unintentional trespass, where the defendant genuinely but mistakenly believes their action is lawful. Ignorance of law is not a defence.

Key Requirements:

The mistake must be one of fact, not law.

The mistake must be reasonable and lead directly to the tortious act.

Types:

Mistake of Identity: Acting against the wrong person or property.

Mistake of Circumstance: Misinterpreting a situation leading to the act.

Example:

Consolidated Co. v. Curtis & Sons (1892): A defendant who mistakenly seized property believing it was theirs was excused from trespass liability, as the mistake was reasonable.

Indian Case Law:

State of West Bengal v. Shew Mangal Singh (1981): Police officers who arrested the wrong person due to a reasonable mistake of identity were not liable, as the error was factual and unintentional.

Explanation: This defence is narrow, applying mainly to torts like trespass or conversion. Courts require the mistake to be honest and reasonable, rejecting claims based on legal ignorance.

10. Judicial Acts

Judicial acts provide immunity to judges and judicial officers for actions performed in their judicial capacity, within their jurisdiction, protecting the independence of the judiciary.

Key Requirements:

The act must be performed in the officer’s judicial capacity.

The officer must act within their jurisdiction or in good faith if mistaken about jurisdiction.

Types:

Absolute Immunity: For judges acting within jurisdiction, even if malice is alleged.

Qualified Immunity: For officers acting in good faith outside jurisdiction.

Example:

Anderson v. Gorrie (1895): A judge was not liable for a wrongful order passed in court, as it was within their judicial authority.

Indian Case Law:

Anowar Hussain v. Ajoy Kumar Mukherjee (1965): A magistrate was not liable for a judicial order issued in good faith within their jurisdiction.

Explanation: This immunity ensures judges can make decisions without fear of personal liability, provided they act within their authority. Acts outside jurisdiction or with malice may attract liability in rare cases.

Burden of Proof:

Defendants must prove a defence’s applicability, except in contributory negligence, where the plaintiff may need to disprove their negligence.

Conclusion

General defences are essential tools in tort law, enabling defendants to avoid liability under specific circumstances. Defences like Volenti Non Fit Injuria, Inevitable Accident, and Act of God address consent, accidents, and natural events, while Contributory Negligence and Private Defence add nuance to fault allocation. Indian cases like State of Rajasthan v. Vidyawati and Ramalinga Nadar v. Narayana Reddiar illustrate their application. For CLAT UG aspirants, mastering these defences, supported by landmark cases, is key to analyzing tort scenarios and excelling in legal reasoning within India’s legal framework.

|

63 videos|174 docs|38 tests

|

FAQs on General Defences of Tort - Legal Reasoning for CLAT

| 1. What are general defences in tort law? |  |

| 2. What is vicarious liability? |  |

| 3. How does the master and servant relationship affect tort liability? |  |

| 4. What is the principal and agent relationship in tort law? |  |

| 5. How does the concept of partnership affect tort liability? |  |