Law of Torts: Vicarious Liability | Legal Reasoning for CLAT PDF Download

What is Vicarious Liability?

Vicarious liability is a legal principle in tort law where a person or entity is held responsible for the wrongful acts (torts) committed by another person, despite not being directly at fault. This liability arises due to a specific relationship between the two parties, such as employer-employee or principal-agent, and ensures that victims can seek compensation from a financially capable party.Purpose: The doctrine promotes accountability, ensures justice for victims, and encourages employers or principals to supervise their agents or employees effectively. It is an exception to the general rule that a person is liable only for their own wrongful acts.

Key Principle: The Latin maxim Qui Facit Per Alium Facit Per Se ("He who acts through another is deemed in law to do it himself") underpins vicarious liability. Additionally, the principle of Respondeat Superior ("Let the principal be liable") holds employers accountable for their employees’ actions within the scope of employment.

Essential Elements

- Relationship: A recognised legal relationship (e.g., employer-employee, principal-agent) must exist between the parties.

- Tortious Act: The act committed by the agent or employee must be a tort (e.g., negligence, fraud, defamation).

- Course of Employment/Authority: The tort must occur within the scope of employment or the authority granted by the principal.

Key Relationships Giving Rise to Vicarious Liability

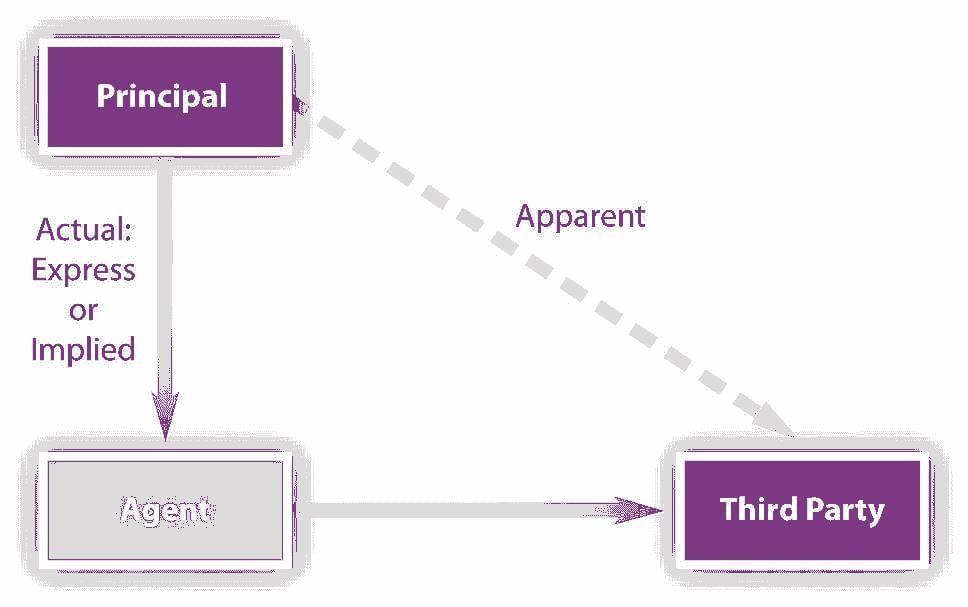

1. Principal and Agent

- A principal authorises an agent to act on their behalf, and the agent executes the authorised acts. The principal is liable for torts committed by the agent within the scope of their authority.

- Types of Authority

1. Express Authority: Explicit instructions given by the principal (e.g., authorising an agent to sell property).

2. Implied Authority: Authority inferred from the task (e.g., an agent negotiating terms during a sale).

3. Apparent Authority: When a third party reasonably believes the agent has authority, the principal may be liable, even if the agent exceeds actual authority (e.g., Lloyd v. Grace, Smith & Co., 1912). - Example: If an agent misrepresents a product’s features during a sale authorised by the principal, the principal is liable for the resulting harm (e.g., Vikram-Prestige Realty scenario).

- Statutory Basis: Section 182 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, defines agents and principals, while Section 238 addresses liability for acts under apparent authority.

2. Partners in a Partnership

- Liability: Under the Indian Partnership Act, 1932 (Section 25), partners are jointly and severally liable for torts committed by a partner in the ordinary course of the partnership’s business.

- Example: If a partner in a law firm commits fraud while advising a client, all partners may be liable for the damages.

- Nature of Liability: Joint and several, meaning the victim can sue any or all partners for the full amount of damages.

3. Master and Servant (Employer-Employee)

- A master (employer) is liable for torts committed by a servant (employee) during the course of employment, based on the principle of Respondeat Superior.

- Course of Employment: Includes acts authorised by the employer or wrongful methods of performing authorised acts (e.g., a driver speeding while making deliveries).

Tests to Identify a Servant:

1. Control Test: The employer controls how the work is done (e.g., a company driver vs. a taxi driver).

2. Hire-and-Fire Test: The employer can appoint or terminate the worker, and the worker receives a salary.

3. Organisation Test: The worker is integral to the employer’s business (e.g., a chef in a restaurant).

Examples:

- In Limpus v. London General Omnibus Co. (1862), the employer was liable for a driver’s negligence in causing an accident, despite instructions not to race, as it occurred during employment.

- Indian Case: In State of Rajasthan v. Vidyawati (1962), the state was liable for a government driver’s negligent driving, as it was within the course of employment.

4. Employer and Independent Contractor

General Rule: Employers are not liable for torts committed by independent contractors, as they lack control over the contractor’s methods.

Exceptions:

1. Non-Delegable Duties: Employers are liable for duties that cannot be delegated, such as ensuring safety on public highways or in hazardous activities (e.g., MC Mehta v. Union of India, 1987).

2. Inherently Wrongful Acts: If the contracted work is illegal (e.g., diverting electricity without permission).

3. Employer’s Interference: If the employer directly controls or interferes with the contractor’s work.

Example: In Kasturi Lal v. State of UP (1965), the state was not liable for a contractor’s theft during a sovereign function (police custody), but liability may arise in non-sovereign functions.

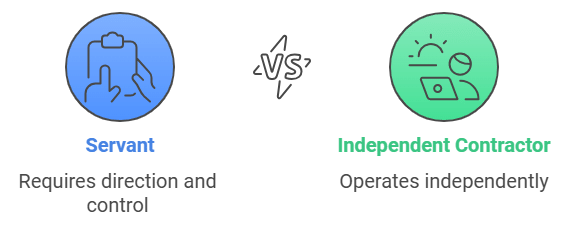

What is the difference between a Servant and an Independent Contractor?

- Servant: A servant is a person employed by another to do work under the directions and control of the master.

- Independent Contractor: An independent contractor is a person who is employed to do a certain task but the master cannot determine the way in which the job is to be done.

The master is not liable for the acts done by the independent contractor.

The master is not liable for the acts done by the independent contractor.

- Example: For example, your driver is your servant, as you can give directions to them on how to drive the car. However, a taxi driver is an independent contractor, as they have been instructed to drive to a certain place. You cannot tell him how to drive his taxi. There are two tests in distinguishing between a servant and an independent contractor:

- Hire and Fire Test: To apply this rule, check whether the person employed can be fired from their job or not. Does he receive a salary as his remuneration for his job? If yes, then this test is fulfilled. However, this test alone does not make a person a servant.

- Direction and Control test: Check whether the person who has to do a job receives directions from the master as to how to do the job. If yes, then he is a servant. If no, he is an independent contractor.

- So, for a person to be called a servant, both tests have to be satisfied, while in the case of an independent contractor, only the first test needs to be satisfied.

Conditions for Vicarious Liability

Vicarious liability in tort law holds a person or entity responsible for the wrongful acts (torts) of another due to their specific relationship. For liability to arise, certain conditions must be met, ensuring the tort is connected to the duties assigned.

1. Existence of a Recognised Relationship

Requirement: A legally recognised relationship must exist between the wrongdoer and the person held liable, such as employer-employee, principal-agent, or partners in a partnership.

Details

1. Employer-Employee (Master-Servant): The employer controls the employee’s work, making them liable for torts committed during employment (e.g., State of Rajasthan v. Vidyawati, 1962).

2. Principal-Agent: The principal authorises the agent to act, incurring liability for acts within the scope of authority, including apparent authority (e.g., Lloyd v. Grace, Smith & Co., 1912).

3. Partners: Under Section 25 of the Indian Partnership Act, 1932, partners are jointly and severally liable for torts in the course of partnership business.

2. Tortious Act

Requirement: The act committed by the employee or agent must be a tort, such as negligence, defamation, fraud, or trespass.

Details: Vicarious liability applies only to civil wrongs, not personal or criminal acts unrelated to duties (e.g., State Bank of India v. Shyama Devi, 1978, where the bank was not liable for an employee’s fraud outside employment).

Example: In Municipal Corporation of Delhi v. Subhagwanti (1966), the employer was liable for employees’ negligence causing a clock tower collapse.

3. Course of Employment or Scope of Authority

Requirement: The tort must occur while the employee or agent is performing authorised duties or acting within the scope of authority.

Details

1. Acts explicitly authorised (e.g., a driver delivering goods).

2. Wrongful methods of performing lawful acts (e.g., a security guard using excessive force).Frolic vs. Detour:

Frolic: A personal act unrelated to employment (e.g., a driver using a company vehicle for a personal trip). No liability (e.g., Beard v. London General Omnibus Co., 1900).

Detour: A minor deviation from duties (e.g., stopping for a break during deliveries). Liability may apply (e.g., Rose v. Plenty, 1976).Prohibitions

1. Prohibitions limiting the scope of employment (e.g., “Do not drive outside city limits”) exclude liability if violated.

2. Prohibitions affecting the mode of work (e.g., “Do not speed”) do not absolve liability (e.g., Limpus v. London General Omnibus Co., 1862).Indian Context: In Pushpabai v. Ranjit G & P Co. (1977), the employer was liable for a driver’s negligence despite instructions against reckless driving.

4. Control Test

Requirement: The wrongdoer must be an employee (under the employer’s control) rather than an independent contractor, who operates independently.

Details:

Degree of Control: Employer dictates how work is done (e.g., a company driver vs. a taxi driver).

Method of Payment: Employees receive salaries; contractors are paid per task.

Provision of Tools: Employees use employer-provided tools.

Hire-and-Fire Authority: Employers can appoint or terminate employees.

Organisation Test: Employees are integral to the business (e.g., a chef in a restaurant vs. a plumber hired for a one-time job).

Examples:

- Case Example: In Mersey Docks and Harbour Board v. Coggins & Griffith (1947), a crane operator was deemed an employee due to employer control.

Indian Case: In Shivnandan Sharma v. Punjab National Bank (1955), a worker under direct control was an employee, making the bank liable.

Exceptions for Independent Contractors:

1. Non-Delegable Duties: Liability for safety on public highways or hazardous activities (e.g., MC Mehta v. Union of India, 1987).

2. Inherently Wrongful Acts: Liability for illegal contracted work.

3. Employer Interference: Liability if the employer controls the contractor’s work.

5. Close Connection to Duty

Requirement: The tortious act must be closely connected to the duty assigned to the employee or agent.

Details: This principle ensures that the wrongful act is not just a random occurrence but is linked to the responsibilities of the employee or agent. For example, if a security guard is responsible for maintaining order and they harm someone while attempting to do so, there is a close connection to their duty.

Examples:

- Case Example: In Storey v. Ashton (1866), a coachman was found liable for injuries caused while deviating from his route, as the act was connected to his duties.

- Indian Case: In K. M. R. S. S. Rajappa v. State of Karnataka (1997), the court held that a driver’s negligent act was closely connected to his duty, making the employer liable.

Modern Applications

- Gig Economy: Courts debate whether gig workers (e.g., delivery app drivers) are employees, impacting liability for accidents or misconduct.

- Data Protection: Employers may be liable for data breaches under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, if committed during employment.

- Workplace Harassment: Liability for employee harassment under the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013.

Gig Economy Insights

Gig Economy Insights

Indian Statutory Framework

- Indian Contract Act, 1872: Sections 182 and 238 govern principal-agent liability.

- Consumer Protection Act, 2019: Liability for employees’ deficient services (e.g., misrepresentation).

- Workmen’s Compensation Act, 1923: Liability for contractors’ workers in specific cases.

Landmark Cases in Tort Law

The following landmark cases illustrate key principles of tort law, particularly vicarious liability, negligence, and strict liability. Each case is summarised with facts, issues, judgments, and principles for a comprehensive understanding of tort law concepts.

1. Ashby v. White (1703)

Facts: A voter was wrongfully prevented from voting by a returning officer, despite no financial loss or physical harm. The candidate the voter intended to support won the election.

Issue: Can a person sue for the violation of a legal right without tangible damage (injuria sine damno)?

Judgment: The court held the officer liable, as the voter’s legal right to vote was violated, entitling him to damages despite no actual loss.

Principle: Injuria sine damno—a breach of a legal right is actionable even without proof of damage. Every person has absolute rights to property, liberty, and personal immunity, and their infringement is sufficient for a cause of action.

2. Gloucester Grammar School Case (1410)

Facts: A teacher left Gloucester Grammar School and opened a rival school nearby, charging lower fees (12 pence vs. 40 pence). This attracted students away, causing financial losses to the original school. The school sued for damages.

Issue: Can financial losses from lawful competition be compensated as a tort?

Judgment: The court dismissed the claim, as the teacher’s actions were lawful and did not infringe any legal right of the school.

Principle: Damnum sine injuria—damage without legal injury is not actionable. Lawful competition, even if causing financial loss, is not a tort unless it involves wrongful acts.

3. Bhim Singh v. State of J & K (1985)

Facts: Bhim Singh, an MLA, was illegally detained by police from September 9–13, 1985, preventing him from attending a legislative assembly session and voting. The detention violated Articles 21 and 22(2) of the Indian Constitution, as he was not produced before a magistrate within 24 hours.

Issue: Was the state liable for the illegal detention and violation of constitutional rights?

Judgment: The Supreme Court held the state liable, awarding damages for the gross violation of Bhim Singh’s right to personal liberty, caused by police misconduct and magisterial negligence.

Principle: Illegal detention constitutes false imprisonment and a constitutional violation, entitling the victim to compensation, especially when done with malicious intent.

Indian Context: Reinforces protections under Articles 21 (right to life and liberty) and 22 (protection against arbitrary arrest).

4. Hall v. Brooklands Auto Racing Club (1933)

Facts: During a car race, two racers took a wrong turn at a bend, causing a car to crash into spectators, resulting in injuries and deaths. The track, operational since 1907, had no prior incidents, and safety measures were in place.

Issue: Were the track owners liable for the spectators’ injuries despite no prior incidents?

Judgment: The court held the owners not liable, as the incident was an unforeseeable accident, and they had taken reasonable precautions.

Principle: Liability for negligence requires foreseeability and a breach of duty of care. Organisers are not liable for unforeseeable accidents if reasonable safety measures are implemented.

5. Stanley v. Powell (1891)

Facts: During a shooting party, a member accidentally shot another, mistaking their movement for an animal. The injured member sued for damages.

Issue: Was the shooter liable for the accidental injury?

Judgment: The court held the shooter not liable, as the plaintiff voluntarily participated in a risky activity, fully aware of the dangers.

Principle: The defence of volenti non fit injuria (voluntary assumption of risk) applies when a plaintiff consents to inherent risks, negating liability.

6. State Bank of India v. Shyama Devi (1978)

Facts: Shyama Devi gave cash and a cheque to a bank employee, Kapil Deo Shukla, for deposit into her savings account. Shukla, acting as a friend, misappropriated the funds and made false entries in the passbook outside his employment duties. Shyama Devi sued the bank.

Issue: Was the bank vicariously liable for the employee’s fraud?

Judgment: The Supreme Court held the bank not liable, as Shukla acted outside the course of employment, in a personal capacity.

Principle: Employers are not vicariously liable for employees’ actions outside the scope of employment, especially when the act is personal or unauthorised.

Indian Context: Clarifies limits of vicarious liability under Indian tort law.

7. Beard v. London General Omnibus Co. (1900)

Facts: An omnibus conductor drove the bus through side streets, off the designated route, and negligently injured a pedestrian. The pedestrian sued the bus company.

Issue: Was the employer liable for the conductor’s unauthorised act?

Judgment: The court held the employer not liable, as the conductor’s act of driving was outside his scope of employment. The plaintiff failed to prove the act was authorised.

Principle: The burden of proof lies on the plaintiff to show that an employee’s tort was within the scope of employment for vicarious liability to apply.

8. Lloyd v. Grace, Smith & Co. (1912)

Facts: Ms. Lloyd sought investment advice from a law firm. The firm’s clerk fraudulently induced her to sign a gift deed (instead of a sale deed), misappropriating the proceeds. She sued the firm.

Issue: Was the firm liable for the clerk’s fraudulent act?

Judgment: The House of Lords held the firm liable, as the clerk acted within the apparent scope of his authority, even though the act was fraudulent.

Principle: Employers are vicariously liable for employees’ torts, including fraud, if committed within the apparent scope of authority, even for personal gain.

9. Limpus v. London General Omnibus Co. (1862)

Facts: A bus driver, despite instructions not to race, overtook another bus, causing an accident. The injured party sued the bus owner.

Issue: Was the employer liable despite the prohibition?

Judgment: The court held the employer liable, as the driver’s act was a wrongful mode of performing his authorised duty (driving).

Principle: Employers are liable for employees’ torts within the course of employment, even if the act violates a prohibition on the mode of work.

10. State of Rajasthan v. Vidyawati (1962)

Facts: A government vehicle, driven negligently by a state employee, injured the plaintiff’s husband. The plaintiff sued the State of Rajasthan.

Issue: Was the state vicariously liable for the employee’s negligence?

Judgment: The Supreme Court held the state liable, as the driver’s act occurred during a non-sovereign function (transport).

Principle: The state is vicariously liable for employees’ torts in non-sovereign functions but not in sovereign functions (e.g., police duties).

Indian Context: Establishes state liability under Indian tort law for non-sovereign activities.

11. Kasturi Lal v. State of UP (1965)

Facts: Kasturi Lal, a jeweller, was arrested on suspicion of possessing stolen goods. His gold and silver were seized and stored in police custody. A head constable stole the goods, and Kasturi Lal sued the state for damages.

Issue: Was the state liable for the loss caused by the constable’s theft?

Judgment: The Supreme Court held the state not liable, as the loss occurred during a sovereign function (police custody).

Principle: The state is not vicariously liable for torts committed during sovereign functions, such as police operations.

Indian Context: Limits state liability compared to Vidyawati, emphasising sovereign immunity.

12. Rylands v. Fletcher (1868)

Facts: The defendant hired a contractor to build a reservoir. The contractor failed to seal disused shafts, causing water to flood the plaintiff’s neighbouring mine.

Issue: Was the defendant liable for the damage despite no negligence?

Judgment: The court held the defendant liable under strict liability, as he brought a dangerous substance (water) onto his land, which escaped and caused harm.

Principle: The rule in Rylands v. Fletcher imposes strict liability for non-natural use of land causing damage, even without negligence.

13. Donoghue v. Stevenson (1932)

Facts: A woman consumed ginger beer containing a decomposed snail, purchased by her friend from a café. She fell ill and sued the manufacturer for negligence.

Issue: Did the manufacturer owe a duty of care to the ultimate consumer?

Judgment: The House of Lords held the manufacturer liable, establishing a duty of care to consumers for defective products.

Principle: The neighbour principle—a person owes a duty of care to those foreseeably affected by their actions, foundational to modern negligence law.

Vicarious liability in Indian law

Vicarious liability in Indian law operates under similar principles to those in many other jurisdictions, but it is deeply rooted in the Indian legal framework and judicial interpretations. This principle holds one party responsible for the actions of another, particularly in employer-employee relationships. In India, vicarious liability is governed by various statutes and case law, ensuring that victims have a means of redress and promoting accountability.

Key Elements of Vicarious Liability in Indian Law

- Relationship: A specific relationship, typically between an employer and an employee, is essential for vicarious liability. This relationship establishes the basis for one party being held responsible for the actions of another.

- Course of Employment: The wrongful act must occur within the scope of employment. This means that the actions of the employee should be related to their job responsibilities and take place while they are employed. Actions that fall outside this scope generally do not trigger vicarious liability.

- Control: The employer must have some degree of control over the actions of the employee. This implies that the employer has the authority to direct and manage the activities of the employee.

Statutory Provisions and Judicial Interpretations

Indian Contract Act, 1872The Indian Contract Act, 1872, lays the foundation for vicarious liability through principles of agency. Section 182 defines an agent as a person employed to do any act for another or to represent another in dealings with third persons, establishing the groundwork for vicarious liability.

Indian Penal Code, 1860

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860 also deals with the concept of vicarious liability. For example, Section 34 of the IPC holds individuals accountable for actions done by multiple people with a common intention, treating each person as if they acted alone. While this section doesn't explicitly mention employer-employee relationships, it demonstrates the principle of shared liability.

Judicial Interpretations

Indian courts have played a significant role in shaping the concept of vicarious liability. Notable cases include:

State Bank of India v. Shyama Devi (1978): The Supreme Court held that an employer could be held liable for fraudulent acts committed by an employee in the course of employment, emphasising the employer's responsibility to supervise and control their employees.

Municipal Corporation of Delhi v. Subhagwanti (1966): In this case, the Supreme Court held the Municipal Corporation liable for the negligence of its employees that resulted in the collapse of a clock tower, causing multiple deaths. This case highlighted the importance of employers maintaining safety and vigilance in their operations.

Practical Applications

Workplace Accidents: Employers in India can be held liable for accidents caused by their employees during work. For example, if a factory worker negligently operates machinery, resulting in injury, the employer may be held responsible for the damages.

Harassment and Discrimination: Indian law holds employers accountable for harassment or discrimination perpetrated by their employees if it occurs within the workplace or during work-related activities. This ensures a safe and respectful work environment.

Torts Committed by Employees: Employers may be held liable for torts such as fraud or defamation committed by their employees during their employment. This underscores the need for employers to implement robust oversight mechanisms.

CLAT Level Passage-Based Questions

1. An employee, Ravi, works as a delivery driver for FastTrack Couriers, a delivery company based in Mumbai. While making a delivery during his regular working hours, Ravi negligently hits a pedestrian, Priya, causing serious injuries. Priya files a lawsuit against FastTrack Couriers for compensation. Additionally, Ravi is found to have committed fraud by falsifying delivery records to steal goods worth ₹50,000 over the past few months. FastTrack Couriers claims that they were unaware of Ravi's fraudulent activities and argues that they should not be held liable for his actions.

Under Indian law, for FastTrack Couriers to be held vicariously liable for Ravi’s accident, which of the following must be true?

A. Ravi was acting outside the scope of his employment.

B. Ravi was acting within the scope of his employment.

C. Ravi’s actions were intentional and malicious.

D. FastTrack Couriers explicitly directed Ravi to hit Priya.

2. Sunita works as a manager at Metro Mart, a large retail chain. One day, during her shift, she instructs a subordinate, Arun, to clean the storage area. While cleaning, Arun negligently leaves a heavy box precariously placed on a high shelf. Later, a customer, Meera, is injured when the box falls on her. Meera decides to sue Metro Mart for her injuries. In a separate incident, it is discovered that Sunita has been embezzling funds from the company over the past year. Metro Mart claims they had no knowledge of Sunita's embezzlement activities and that they should not be held liable for her fraudulent acts.

What argument could Metro Mart use to defend against the vicarious liability claim for Arun’s negligence?

A. Arun was not acting within the scope of his employment

B. Arun was an independent contractor

C. Sunita was not involved in the incident

D. Meera contributed to her own injuries

3. Ajay is a software engineer working for TechSolutions Pvt. Ltd., an IT company based in Bangalore. During his employment, Ajay is assigned to handle sensitive customer data. Without authorisation, he accesses and sells confidential customer information to a third party. When this unauthorised data breach is discovered, several customers file lawsuits against TechSolutions for breach of privacy and data protection. TechSolutions claims that Ajay acted independently and outside the scope of his employment and argues that they should not be held liable for his actions.

Which legal principle would support TechSolutions’ defence that they should not be held liable for Ajay’s actions?

A. Res ipsa loquitur

B. Doctrine of common intention

C. Ajay acted outside the scope of his employment

D. Employer’s control over the employee

4. Vikram is a real estate agent working for Prestige Realty, a prominent real estate agency in Chennai. During a property showing, Vikram negligently misrepresents the features of a house, claiming it has modern amenities and no structural issues. Based on Vikram's representation, a prospective buyer, Anjali, purchases the property. Shortly after the purchase, Anjali discovers that the house has significant structural problems and lacks the amenities Vikram promised. Anjali files a lawsuit against Prestige Realty, seeking damages for the misrepresentation.

What key factor will be considered to determine whether Prestige Realty is liable for Vikram’s misrepresentations?

A. Whether Vikram was an independent contractor

B. Whether Vikram’s actions were authorised by Prestige Realty

C. The amount of damages claimed by Anjali

D. Prestige Realty’s knowledge of Vikram’s previous misrepresentations

Solutions

Q1.

View Answer

View Answer

B. Ravi was acting within the scope of his employment.

Explanation:

Vicarious liability requires that the wrongful act be performed within the scope of the employee's employment. This means that FastTrack Couriers can be held liable for Ravi’s actions if Ravi was performing his job duties as a delivery driver when the accident occurred.

Scope of Employment: If Ravi was making a delivery during his working hours and his negligence was part of his job duties, FastTrack Couriers would be liable for the damages caused by the accident.

Out of Scope: If Ravi’s actions were unrelated to his job (e.g., if he was not performing his delivery duties or engaged in personal activities), the company might not be held liable.

Intent and Direction: The specific intent of Ravi’s actions or whether FastTrack Couriers directed him to hit Priya is not relevant for vicarious liability. The focus is on whether the actions were within the scope of employment.

Q2.

View Answer

View Answer

Explanation:

For Metro Mart to avoid vicarious liability, they could argue that Arun was not acting within the scope of his employment when the negligence occurred.

Scope of Employment: If Arun’s negligence was unrelated to his job duties (e.g., if he was instructed to clean but did so negligently in a way that was not part of his job), Metro Mart might not be held liable.

Independent Contractor: If Arun were an independent contractor, Metro Mart might not be liable, but since he is a subordinate, this argument is less relevant.

Involvement of Sunita: Sunita’s embezzlement is unrelated to Arun’s negligence and does not affect Metro Mart’s liability for the incident involving Meera.

Contributory Negligence: Meera’s potential contributory negligence does not directly impact Metro Mart’s vicarious liability for Arun’s negligence.

Q3.

View Answer

View Answer

Explanation:

TechSolutions’ defense that Ajay acted outside the scope of his employment is key to avoiding vicarious liability.

Scope of Employment: If Ajay accessed and sold confidential information outside the duties assigned to him by TechSolutions, the company can argue that Ajay’s actions were not performed within the scope of his employment.

Res ipsa loquitur: This principle (the thing speaks for itself) is not applicable here as it relates to situations where the fault is apparent from the occurrence itself.

Doctrine of Common Intention: This principle deals with shared intent among multiple parties, not relevant to individual employment actions.

Employer’s Control: While TechSolutions does exercise control over Ajay, the key issue is whether the wrongful act was part of his job duties.

Q4.

View Answer

View Answer

Explanation:

For Prestige Realty to be held liable for Vikram’s misrepresentations, it is crucial to determine if Vikram’s actions were authorized by the company.

Authorization: If Vikram’s misrepresentations were made in the course of his employment and were related to his duties as a real estate agent, Prestige Realty may be held liable.

Independent Contractor: If Vikram were an independent contractor, Prestige Realty might not be liable, but if he is an employee, this argument is less relevant.

Amount of Damages: While damages are important for calculating compensation, they do not directly determine liability.

Previous Misrepresentations: The focus is on whether the specific act of misrepresentation was within the scope of Vikram’s employment, not on the company’s knowledge of previous actions.

|

63 videos|174 docs|38 tests

|

FAQs on Law of Torts: Vicarious Liability - Legal Reasoning for CLAT

| 1. What is vicarious liability in the context of law of torts? |  |

| 2. What is the difference between a servant and an independent contractor in the law of torts? |  |

| 3. How does the concept of "course of employment" affect vicarious liability in the law of torts? |  |

| 4. What is the extent of liability of a master in cases of vicarious liability in the law of torts? |  |

| 5. How do dishonest and criminal acts by an agent or employee impact vicarious liability in the law of torts? |  |