Aesthetics and Empire, c. 300–600 CE - 3 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Guilds and Inscriptions |

|

| R. S. Sharma's Argument |

|

| Money-lending Practices |

|

| Nalanda: Bodhisattva |

|

Guilds and Inscriptions

- The flourishing condition of guilds during the Gupta period is evident from various inscriptions. Guilds are referred to as donors and bankers in these inscriptions.

- The Indore plates of the Vakataka king Pravarasena mention a merchant named Chandra, who bought half of a village gifted by the king to certain Brahmanas. This indicates the involvement of guilds in local affairs.

- The Gadhwa inscription from the time of Chandragupta II (407 CE) mentions an investment of 20 dinaras in a guild headed by Matridasa for the benefit of Brahmanas.

- Two other inscriptions from Gadhwa, belonging to the reign of Kumaragupta I, record investments of 13 and 2 dinaras with two guilds for the maintenance of sattras (almshouses).

- The Indore inscription of Skandagupta (465 CE) records an endowment made by a Brahmana Devavishnu for maintaining a perpetual lamp in a Surya temple at Indrapura (Indore).

- The inscription states that the temple was built by two merchants, Achalavarman and Bhrikunthasimha, and that the money for the perpetual lamp was invested with a guild of oil manufacturers headed by Jivanta.

- The guild was responsible for ensuring a regular supply of oil for the lamps in the temple, even if it migrated to a different location.

R. S. Sharma's Argument

- R. S. Sharma argues that during the Gupta and post-Gupta periods, there was a decline in the money economy.

- He points out that while the Guptas issued many gold coins, they issued comparatively fewer silver and copper coins.

- Recent finds have challenged the earlier belief that the Vakatakas did not issue any coins.

Money-lending Practices

- The Narada Smriti, an ancient text, refers to money gained through usury (lending money at high interest rates) as ‘spotted wealth’ and ‘black wealth’.

- Dharmashastra texts from the same period lay down detailed rules concerning usury, including the drawing up of contracts, local customs in fixing interest rates, and types of pledges that can be accepted as security for loans.

- A general rate of 15 per cent per annum interest is recommended for secured loans.

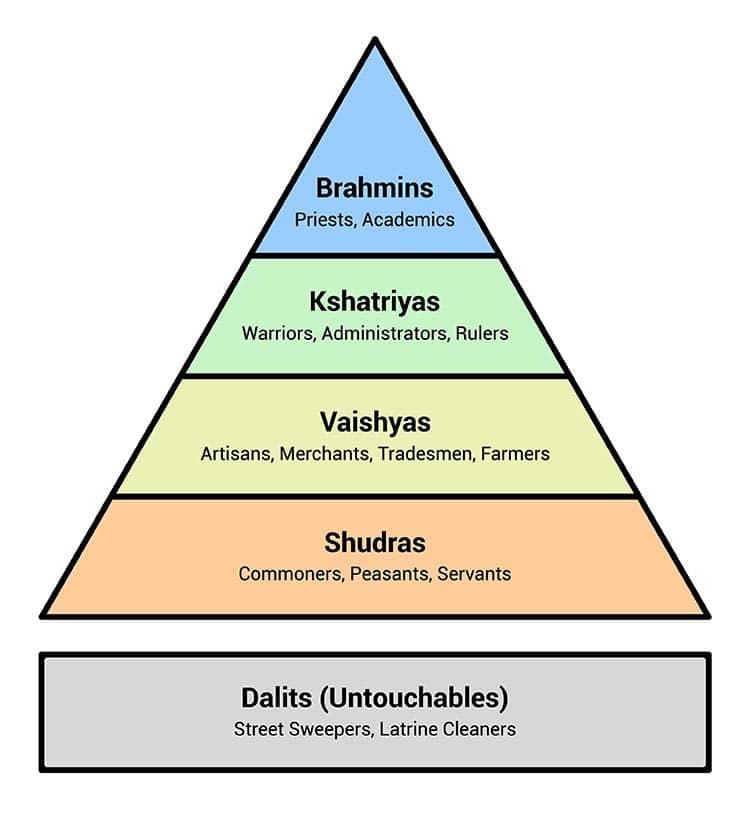

- Interest rates for unsecured loans are higher and vary based on the varna (social class) of the borrower, with members of lower varnas paying higher rates.

- The Brihaspati Smriti states that when a piece of immovable property, such as land, has been enjoyed and has yielded more than the principal, the debtor should automatically recover the pledge.

- The Narada Smriti asserts that the consequences of defaulting on a loan pursue the debtor in the next life, with the debtor being born as a slave in the house of his creditor to pay off the debt through labor.

The Silk Trade: India's Role and Chinese Influence

- Indian Exports: Historical Trade Goods:

- Rare gems

- Pearls

- Fine textiles, likely muslin

- Saffron

- Spices, including pepper

- Aromatics

- Silk Production in India: Indigenous Methods:

- Indian artisans used wild silkworm cocoons.

- They collected damaged cocoons, spinning yarn from the floss.

- Lack of Advanced Techniques:

- Mulberry silk production and boiled cocoon methods were unknown in India until the 13th century.

- Comparison with Chinese Silk: Quality Differences:

- Indian silk was less soft and shiny than Chinese silk.

- Chinese silk remained a luxury item, highly sought after even after Indian production improved.

- Trade Dynamics: Continued Imports:

- India imported silk yarn and cloth from China.

- Indian merchants played a key role in transporting Chinese silk to the Mediterranean.

- Export Practices:

- Silk exported from India was often Chinese silk, not locally produced.

- Cultural References: Kalidasa's Works:

- Mention of chinamshuka, or Chinese silk, worn by the wealthy.

- Chinese Trade: Gifts and Exports:

- Chinese emperors gifted silk to foreign embassies.

- Silk was a significant item in Chinese trade with India and beyond.

Kaveripattinam and Coastal Trade

- Kaveripattinam was an important port in Tamil Nadu, with evidence of human activity from the 3rd century BCE to the 12th century CE.

- Excavations revealed a bustling settlement with evidence of trade, including a brick Buddhist vihara and a multi-storeyed temple from the 4th to 6th centuries CE.

- The coastal trade network extended to flourishing settlements in Sri Lanka, such as Mantai, Kirinda, and Godavaya, indicating a vibrant maritime economy.

Aspects of Social Structure: Gender, Forms of Labour, Slavery, and Untouchability

- Pilgrims like Faxian aimed to help devout Buddhists in China visualize places and events from the Buddha's life. That's why there are not many detailed accounts of Indian everyday life in his writings. Instead, Faxian paints a rosy and idealized picture of 5th-century Indian society, depicting people as happy and content, living in peace and prosperity. He notes that they didn't have to register their households or deal with magistrates. Farmers working on royal land simply had to give a portion of their produce to the king.

- More accurate details about social life during this period come from other sources. Royal women, for instance, are seen on coins and seals. Some coins feature queens, like those of Chandragupta I and his wife Kumaradevi. Coins from later rulers like Kumaragupta I and Chandragupta II show queens in various poses, reflecting their roles in rituals like the ashvamedha sacrifice.

- Matrimonial alliances were crucial in the politics of the time, as seen in Gupta inscriptions that mention queens. In contrast, the Vakataka genealogies typically do not include references to queens.

Matrimonial Alliances in Gupta and Vakataka Inscriptions

- During the Gupta period, matrimonial alliances were a significant aspect of political life, as evidenced by the mention of queens in inscriptions like the Allahabad prashasti of Samudragupta and the Bhitari pillar inscription of Skandagupta. In contrast, the genealogies of the Vakataka dynasty typically do not highlight queens.

- However, Vakataka inscriptions do reveal the political influence of queen Prabhavatigupta, who exercised power during the reigns of three successive Vakataka rulers. Some royal women also took the initiative in making donations. For instance, Prabhavatigupta was known to make grants in her own right. The Masoda plates of Pravarasena II also mention a grant made at the request of a chief queen, whose name is not specified.

Polygynous Alliances in Ancient Society

The practice of polygynous alliances among kings is well-documented. The Kamasutra, an ancient Indian text, indicates that polygyny was also common among certain sections of the non-royal elite. For example, the Ghatotkacha cave inscription of Varahadeva provides a detailed genealogy of the donor’s family, mentioning a person named Soma. Soma is described as having taken wives from both Kshatriya and Brahmana communities.

According to the inscription, Soma had a son named Ravi with royal attributes from his Kshatriya wife, and sons well-versed in the Vedas from his Brahmana wives. This suggests that polygynous alliances were not limited to royalty but were practiced by other segments of society as well.

Primary Sources

Faxian's Account

- Faxian's Gaoseng Faxian zhuan, the earliest firsthand Chinese account of Buddhist sites and practices in India, significantly shaped Chinese perceptions of the Indian subcontinent.

Background of Faxian

- Faxian embarked on his journey to India at the age of over 60, leaving Chang'an, and returned to China around the age of 77.

- His primary goal was to obtain and bring back texts containing monastic rules.

Focus of the Account

- Faxian's account primarily emphasizes Buddhist monasteries in various parts of northern India, detailing the number of monks, their practices, and descriptions of places of Buddhist pilgrimage.

- The account includes legends associated with these pilgrimage sites.

- There are very few descriptions of the lives of ordinary people, and when they are included, they tend to be idealized.

Excerpt from Faxian's Account

At Mathura

- South of Mathura is known as the Middle Kingdom.

- The climate is pleasant, without extreme cold or heat, and there is no hoarfrost or snow.

- The population is large and content, and there is no need for household registration or strict magistrates.

- Only those who cultivate royal land must pay a portion of their gains.

- People have the freedom to come and go as they please, and the king governs without harsh corporal punishments.

- Criminals are fined based on the circumstances of their offenses, and even in cases of rebellion, punishments are relatively mild, such as the cutting off of a hand.

- The king's bodyguards and attendants receive salaries, and throughout the country, people do not kill living creatures, consume intoxicating liquor, or eat onions or garlic.

- The only exception is the Chandalas, who are considered wicked and live apart from others.

- Chandalas announce their presence by striking a piece of wood when entering a city or marketplace to avoid contact with others.

- In this region, there are no pig or poultry farms, and live cattle are not sold.

- Markets do not have butchers' shops or dealers in intoxicating drinks.

At Mathura

- Geography and Climate: Mathura is located in a region known as the Middle Kingdom, which is characterized by a pleasant and moderate climate. There is no extreme cold, hoarfrost, or snow in this area.

- Society and Governance: The people of Mathura are numerous, happy, and live without the need for household registrations or strict magistrate oversight. Only those who farm royal land are required to pay a portion of their harvest to the king. Residents have the freedom to come and go as they please.

- Criminal Justice: The king governs with a focus on fines rather than corporal punishments. Even serious offenders face lighter penalties, with repeated rebels only having their right hands severed. The king’s guards and attendants receive salaries for their service.

- Dietary Restrictions and Practices: The people of Mathura do not kill animals, consume alcohol, or eat onions and garlic. The Chandalas, a marginalized group, are the exceptions to this rule. They are considered outcasts, signal their presence by striking a piece of wood, and live separately from the rest of the population.

- Market Practices: In Mathura’s markets, cowries are used as currency. The Chandalas are the only ones permitted to fish, hunt, and sell meat.

At Pataliputra

- Cities and Towns: Pataliputra boasts the largest and most prosperous cities and towns in the Middle Kingdom. The inhabitants are wealthy and compete in acts of kindness and righteousness.

- Annual Festival: Every year, on the eighth day of the second month, a grand procession of images takes place. A four-wheeled cart is constructed, supporting a five-storey structure resembling a stupa, adorned with colorful cloth and figures of deities. Up to twenty such carts may be present, each unique and impressive.

- Religious Practices: Monks and laypeople come together for this festival, featuring singers and skilled musicians who offer flowers and incense. Brahmanas invite the Buddhas to enter the city, where they stay for two nights, during which offerings and musical performances continue. This practice is common in other kingdoms as well.

- Charitable Activities: Heads of Vaishya families in the cities establish houses for charity and medicine. These houses provide assistance to the poor, including orphans, widowers, the childless, disabled individuals, and the sick. Doctors examine their ailments, and they receive necessary food and medicines, leaving when they are well.

Ganika (Courtesan)

- The ganika was a key figure in kavya literature, representing the feminine counterpart of the nagaraka (urban man) and embodying the city’s refined culture. While both veshyas (common prostitutes) and ganikas are mentioned in kavya, the focus is more on the latter. Ganikas were wealthy courtesans who lived in spacious, well-appointed homes, unlike ordinary prostitutes who resided in crowded brothels.

- The household of a ganika was typically managed by her mother and included various staff members such as maidservants, female messengers, musicians, and other professionals, along with children. The ganika was not only a provider of sexual pleasure but also a connoisseur of culture and refinement, much like the nagaraka. The Kamasutra outlines a wide range of skills and arts that a ganika should master, including etiquette, singing, dancing, playing musical instruments, painting, preparing drinks, performing magic tricks, telling jokes and riddles, staging plays, composing poetry, and having knowledge of literature and gambling.

- Unlike the kulastri (wife), whose behavior was expected to be modest and reserved, the ganika was free to interact with men and accompany them to social events. However, both the ganika and the kulastri had no say in choosing their romantic partners. Kaul suggests that the emphasis on courtesans in kavya may reflect a fascination with a new and intriguing model of female behavior that combined sensuality with intellect.

Kulastri (Wife)

- The kulastri (wife) is another important figure in Sanskrit kavya literature, often depicted in contrast to the ganika (courtesan). While ganikas are portrayed as sophisticated and socially active women, kulastri are characterized by their modesty and demureness. The kulastri represents the ideal of a virtuous wife, whose behavior is strictly regulated by societal norms.

- Unlike the ganika, who is celebrated for her beauty, intellect, and refinement, the kulastri is expected to maintain a low profile and serve her husband and family without drawing attention to herself. This difference highlights the varying ideals of femininity in kavya literature.

- The ganika was a woman of great desirability, admired not only for her physical beauty but also for her refinement and intellect. In contrast to the kulastri, who was expected to be extremely modest and demure, the ganika interacted freely with men, joining them at parties, picnics, and various festivities. However, it is important to note that neither the ganika nor the kulastri had the freedom to choose whom they loved. Kaul suggests that the allure of courtesans in Sanskrit poetry may stem from a fascination with a new and enticing model of female behavior that skillfully blended sensuality with intellect.

- The portrayal of the ganika in kavyas is characterized by ambivalence and is at the heart of several dilemmas and contradictions. Her conduct code stressed that her aim should be a mercenary desire for profit rather than love.

The Ganika in Kavyas

- The ganika was a highly desirable woman known for her beauty, refinement, and intelligence. Unlike the kulastri, who had to be modest and demure, the ganika interacted freely with men, attending parties, picnics, and festivities with them.

- Both the ganika and the kulastri, however, had no choice in whom they loved. Kaul suggests that the fascination with courtesans in Sanskrit poetry may reflect an interest in a new model of female behavior that combined sensuality and intellect.

The Ganika's Code of Conduct

- The ganika's code of conduct emphasized a mercenary desire for profit rather than love.

- A dilemma arose when a ganika fell in love with a poor man, as seen in the case of Vasantasena and Charudatta.

- The ganika was portrayed as a beautiful and accomplished woman, but desiring her came with a sense of shame.

- Men involved with a ganika often concealed their relationship, as she could never attain social respectability due to the very qualities that defined her.

Vasantasena and Charudatta: A Case Study

- Vasantasena, a ganika, fell in love with Charudatta, a poor man, which created a conflict in her code of conduct.

- Despite being a beautiful and accomplished woman, Vasantasena's desire for Charudatta was problematic because it went against the expectation of mercenary profit.

- The relationship between a ganika and a man was often viewed with shame, and men involved with ganikas had to keep their relationships hidden.

- The qualities that made the ganika desirable also prevented her from achieving social respectability.

The Kamasutra on Marriage and Sexual Relations

Progeny, Fame, and Social Approval

- A man can obtain progeny, fame, and social approval by marrying a virgin of the same varna according to religious rites.

- The Kamasutra emphasizes the importance of following religious guidelines in such marriages.

Restrictions on Sexual Relations

- The Kamasutra forbids sexual relations with women of higher varnas and with married women.

- However, it permits sexual relations purely for pleasure with women of certain lower varnas, treating them on par with relations with prostitutes and remarried widows.

Types of Marriage

- Vatsyayana discusses marriages arranged by parents or guardians, leading to various types of marriage mentioned in the shastras, such as Brahma, Prajapatya, Arsha, or Daiva.

- He also acknowledges marriages based on mutual love and those where girls select their groom, indicating a degree of flexibility in marital arrangements.

Elite Marriages in Dramas

- Dramas from this age mention marriages within elite groups, suggesting that such practices were accepted and perhaps even celebrated in certain social circles.

Duties of a Good Wife

- According to the Kamasutra, a good wife is one who serves her husband diligently and keeps the house clean and well-decorated.

- She is also responsible for managing the servants and household finances efficiently.

- A good wife is dutiful and submissive, waiting on her husband and attending social occasions only with his permission.

- She entertains her husband's friends, serves her in-laws, and obeys their orders.

- Daily Worship and Restraint

- A good wife worships every day at the household shrine.

- When her husband is away, she leads a restrained life, wearing only the minimum ornaments and performing religious rituals and fasts.

- She goes out of the house only when essential and grows different sorts of plants and trees in the garden.

- Knowledge and Skills

- A good wife should have knowledge of agriculture, cattle rearing, spinning, and weaving, and know how to take care of her husband's pets.

- She should also ensure that her husband's finances do not suffer when he is away.

- Relationship with Co-wives

- If a wife has a co-wife, she is expected to look upon her as a sister or mother, depending on their relative age.

- The Katyayana Smriti

- This ancient text states that a wife must always live with her husband, be devoted to him, and worship the domestic fire.

- A wife should attend to her husband while he is alive and remain chaste after his death.

Ganikas in Kamasutra and Sanskrit Kavya Literature

Ganikas are courtesans mentioned in the Kamasutra and Sanskrit kavya literature. These women are portrayed with a mix of admiration and criticism.

Vasantasena is the most famous ganika, known for her beauty and intelligence. In the play Mrichchhakatikam, she is a central character who represents the complex nature of ganikas.

Ambivalent Attitude

- On one hand, ganikas are celebrated for their talents and charm.

- On the other hand, because their sexual services are for sale, they can never achieve true social respectability.

Ordinary Prostitutes

- The texts also mention ordinary prostitutes, who lead lives lacking the glamour and wealth of ganikas.

- These women do not enjoy the same level of admiration and are often seen in a negative light.

Adultery and Social Status

- The Kamasutra takes a practical view of sexual relations between men and married women.

- However, Dharmashastra texts consider adultery by women a lesser sin, requiring penances.

- Some texts suggest that an adulterous woman regains her purity after her menstrual period.

- The Narada Smriti prescribes harsh punishments for adulterous women, including shaving their heads and living in poor conditions.

- The consequences of adultery vary based on the social status of the individuals involved.

- For example, a woman committing adultery with a Shudra or low-caste individual faces different repercussions.

Adultery and Women’s Purity

- The Kamasutra discusses sexual relations between men and married women in a practical and straightforward manner. However, texts on Dharmashastra viewed adultery by women as a lesser sin, called upapataka, for which penances were prescribed.

- Some texts believed that penance was unnecessary and that an adulterous woman regained her purity after her menstrual period.

- For instance, the Narada Smriti outlined strict punishments for adulterous women, including shaving their heads, lying on a low bed, receiving poor food and clothes, and dedicating themselves to cleaning their husband’s house.

- The social status of the individuals involved played a significant role in the severity of the punishment.

- If a woman committed adultery with a Shudra or a low-caste man, her husband was advised to abandon her.

- Conversely, a virtuous wife was to be cherished, and her husband faced penalties for deserting her.

- For example, the Narada Smriti specified that a man owed one-third of his estate or a fine for abandoning a virtuous wife.

Widowhood and Remarriage

- Dharmashastra texts maintained that widows should lead celibate and austere lives.

- The Brihaspati Smriti suggested the drastic option of self-immolation on the husband’s funeral pyre.

- Instances of this practice, known as sahamarana or sahagamana, were recorded in the Mahabharata , such as Madri, the wife of Pandu, and some of Vasudeva’s wives.

- Widow remarriage was generally viewed unfavorably, although it did occur. The Amarakosha indicated this by providing synonyms for a remarried widow (punarbhu ), her husband, and for a dvija who had a punarbhu as his principal wife.

- Katyayana addressed the inheritance rights of the son of a remarried widow and the property rights of a son born to a woman who had left her impotent husband. Vatsyayana acknowledged widows who took lovers, indicating a complex social reality regarding widowhood.

Stri-Dhana and Women’s Position

- While texts from this period increasingly emphasized the subordinate and dependent role of women, there was also an expansion in the scope of stri-dhana, which refers to the wealth and property given to women.

- The Katyayana Smriti categorized stri-dhana into various types, including:

- Adhyagni stri-dhana : Gifts given to women at the time of marriage before the nuptial fire.

- Adhyavahanika stri-dhana : Gifts obtained by a woman when being taken in a procession from her father’s house to the groom’s house.

- Pritidatta stri-dhana : Gifts given out of affection by a woman’s father-in-law or mother-in-law, or received by her at the time of performing obeisance at the feet of elders.

- Shulka (bride’s fee) : Gifts obtained as the price of household vessels, beasts of burden, milch cows, ornaments, and slaves.

- Anvadheya (subsequent gift) : Gifts obtained after marriage from members of the husband’s family and from the family of the wife’s kinsmen.

- Saudayika : Property obtained by a married woman in her husband’s or father’s house or by an unmarried girl from her parents or brothers.

- Katyayana’s descriptions of adhyagni and adhyavahanika stri-dhana were broad, allowing for gifts from non-kinfolk and strangers, as well as gifts received on special occasions other than marriage.

Stri-Dhana in Ancient India

The Katyayana Smriti outlines various forms of stri-dhana, which reflect the scope and nature of gifts and property given to women.

Forms of Stri-Dhana:

- Adhyagni Stri-Dhana: Gifts given to women at the time of marriage before the nuptial fire.

- Adhyavahanika Stri-Dhana: Gifts received by a woman during the procession from her father’s house to her husband’s house.

- Pritidatta Stri-Dhana: Gifts given out of affection by in-laws or received during rituals of respect.

- Shulka (Bride’s Fee): Compensation obtained for household items, livestock, and slaves.

- Anvadheya (Subsequent Gift): Gifts received after marriage from her husband’s family or her father’s kin.

- Saudayika: Property obtained by a married woman in her husband’s or father’s house or by an unmarried girl from her family.

Forms of Labour and Wage Payment:

- Texts from this period mention various forms of hired labour, including farming, field watching, harvesting, cattle tending, craft production, and household work.

- The Brihaspati and Narada Smritis provide guidelines for wage payment, allowing for payment in cash or kind.

- Payment in kind could involve a share of items such as grain, milk, or domesticated animals.

- The Narada Smriti specifies that wages should be paid at a fixed time as per agreement, and if not predetermined, the worker is entitled to a share of the profit.

- The Brihaspati Smriti outlines entitlements for farm servants, including a share of the crop along with food and clothing.

Forced Labour (Vishti):

- Forced labour, known as vishti, became more prevalent during this period and was considered a source of income for the state, akin to a tax paid by the people.

- This practice is often mentioned alongside taxes in land grant inscriptions, indicating its significance.

- The prevalence of vishti is noted to be higher in regions such as Madhya Pradesh and Kathiawar, based on the concentration of inscriptions referring to this practice.

Forced Labour and Slavery in Ancient India

- During this period, forced labour, known as vishti, became more prevalent. It is mentioned alongside taxes in land grant inscriptions, indicating that it was viewed as a source of income for the state, similar to a tax paid by the people.

- Most inscriptions referring to vishti come from the Madhya Pradesh and Kathiawar regions, suggesting that this practice was more common in these areas.

Types of Slaves in Ancient Texts

- The Narada Smriti provides a detailed list of 15 types of slaves, which is more extensive than those found in the Arthashastra and Manu Smriti. These types include:

- War captives reduced to slavery.

- Debt enslavement.

- Voluntary enslavement.

Ownership and Treatment of Slaves

- Slaves could be passed down to the descendants of their owners along with other property.

- They were primarily used as domestic servants or personal attendants.

- A child born to a slave woman in a master’s house was also considered the master’s slave.

Rights and Manumission of Slaves

- The Narada Smriti states that a slave can be pledged or mortgaged, and their services can be hired out by the master.

- It prescribes severe punishments for crimes such as abducting a slave woman, including the amputation of the offender’s foot.

- Manumission, or the act of freeing a slave, is detailed in the Narada Smriti. A slave could be freed only at the master’s discretion, and the ceremony involved specific rituals, such as breaking a jar of water from the slave’s shoulder and sprinkling parched grain and flowers over their head while reciting, “You are no longer a dasa” (slave).

Untouchability in Ancient India

- Faxian, a Chinese monk, reported that Chandalas (a marginalized community) were required to live outside towns and marketplaces. They had to announce their approach by striking a piece of wood to prevent touching others, as their touch was considered impure.

- In South India, the concept of untouchability appears to have developed during the late Sangam period. The Acharakkovai, a Tamil text, describes water touched by a pulaiya (a community considered lower in the caste hierarchy) as defiled and unsuitable for consumption by higher castes. It also states that even seeing a pulaiya was polluting.

- Tamil epics from this period, such as the Manimekalai, further illustrate the practice of untouchability. In the Manimekalai, Brahmanas (Brahmins) are advised not to touch Aputtiran, the son of a Brahmana woman and a Shudra male, to avoid pollution.

Untouchability in Ancient India

According to Faxian, Chandalas, who were considered lower in the social hierarchy, were required to live outside of towns and marketplaces. When they approached, they had to strike a piece of wood to alert others, allowing people to move out of their way to avoid physical contact with them. This practice highlights the strict social boundaries and the concept of untouchability prevalent during that time.

In South India, the practice of untouchability seems to have developed during the late Sangam period. A text called the Acharakkovai indicates that water touched by a pulaiya (a person from a lower caste) was considered polluted and unfit for consumption by higher caste individuals. It even suggested that merely looking at a pulaiya was impure.

The Tamil epics also reference untouchability. For instance, in the Manimekalai, Brahmanas are advised not to touch Aputtiran, the son of a Brahmana woman and a Shudra man, to avoid pollution. These examples illustrate the deep-rooted nature of untouchability in ancient Indian society.

The epics and Puranas elaborate on the problems of the Kali age, depicting a decline from an ideal Krita age. This notion of decline might reflect a historical crisis after 300 CE. The evils of the Kali age mentioned in these texts include:

- Dishonesty among people.

- Failure of the four varnas to adhere to their duties.

- Replacement of yajnas, gifts, and vratas with other practices.

- Rule by mlechchha kings.

- Depopulation of lands, overtaken by wild animals, snakes, and insects.

- Unchaste women.

- Decreased milk production by cows.

- Irregular rainfall.

- Fraudulent practices by traders.

- Shortened lifespans and early baldness.

These descriptions reflect concerns about the fragile social order and its susceptibility to disorder. While advocating for an ideal social and political structure, these texts acknowledged the disparity between ideals and reality. The concept of the four yugas also explains variations in behavioral norms over time, as different dharmas were believed to be suitable for different yugas according to the Dharmashastra tradition.

Patterns of Religious Developments

The period from around 300 to 600 CE is commonly viewed as a time of 'Brahmanical revival' or the strengthening of Brahmanical ideology. This is evident in the solid establishment of Sanskrit as the language for royal inscriptions and the growing popularity of temple-based sectarian cults. In reality, 'Brahmanism' was evolving into a new synthesis that can be described as Hinduism or smarta religious practice, which is based on the Smritis. The roots of this transformation can be traced back to earlier centuries, and its history after the 6th century will be explored in the next chapter.

- The evolution of Hindu religious ideas and practices during this period can be observed through various sources, including the Puranas, religious sculpture and architecture, and inscriptions.

- The Puranas mention different rites, vows, and pilgrimage sites as integral parts of religious practice.

Emergence of Sectarian Symbols

- Sectarian symbols began to appear on seals, indicating specific religious affiliations.

- For example, the Bhita seals feature numerous legends and symbols associated with Shaiva and Vaishnava traditions, such as the linga, trishula, bull, Gaja-Lakshmi, shankha (conch), and chakra (wheel).

Royal Prashastis and Sectarian Affiliations

- Royal prashastis (inscriptions praising kings), coins, and seals often proclaimed the sectarian affiliations of rulers.

- Some Gupta kings identified themselves as Bhagavatas, worshippers of Vasudeva Krishna, while most Vakataka kings described themselves as devotees of Shiva, with a few as devotees of Vishnu.

Rise of Major Hindu Cults

- During this period, major Hindu cults focusing on the worship of Vishnu, Shiva, and Shakti gained increasing popularity.

Growth of Jaina and Buddhist Establishments

- Literary and archaeological evidence also points to the growth of Jaina establishments in regions like Karnataka, while Buddhist monastic centres can be identified in various parts of the subcontinent.

- Royal and non-royal donative inscriptions offer insights into the social groups patronizing these religious establishments.

Religious Interaction and Shared Practices

Evidence from literature and archaeology indicates the expansion of Jaina establishments, particularly in regions like Karnataka, while Buddhist monastic centres are found in various parts of the subcontinent. Inscriptions from both royal and non-royal donors shed light on the social groups supporting these religious establishments.

- Despite their distinct features and doctrines, different religious and cultic traditions existed within an interactive cultural environment. It is not surprising that their paths occasionally overlapped and intersected. For instance, iconic worship in shrines was a common practice among Hindu cults, Jainism, and Buddhism.

- This is evident in the close proximity of Hindu and Jaina caves at Badami, as well as the coexistence of Hindu, Jaina, and Buddhist shrines at sites like Ellora and Aihole.

- Architectural styles and sculptural embellishments often transcended sectarian lines. There are notable similarities among Hindu, Buddhist, and Jaina cave shrines, as well as between Jaina and Hindu structural temples.

- Over time, shrines from various religious traditions shared a common repertoire of auspicious symbols and decorative elements. For example, the medallion-type ornamentation and motifs like garland bearers found at the Buddhist site of Amaravati bear a resemblance to later Hindu shrines in Aihole and Pattadakal.

- This shared pool of symbols and expressions can be attributed to the collective efforts of architects and artisans who conceptualized and executed these works.

Evolution of Deity Associations and Syncretism

The connections and associations among different Hindu deities are prominently displayed in the sculptural designs of various temples. While the main deity is usually the focal point, a wide array of other gods and goddesses are also depicted, showcasing their interconnections.

- The formation of pantheons and the emergence of composite deities, such as Hari-Hara (a fusion of Vishnu and Shiva), reflect these associations.

- The integration of the Buddha into Vishnu’s avatars is often cited as an example of the religious syncretism of the period.

- For instance, Indra, Vishnu, Rama, Hara, and Kama are mentioned in a donative inscription by Varahadeva, a minister of the Vakataka king Harishena, in one of the Buddhist caves at Ajanta.

- Similarly, the Silappadikaram describes a Jaina arhat using epithets of Shiva and Brahma, such as Shankara, Chaturmukha, Ishana, and Svayambhu, further illustrating the blending of religious identities.

- The intricate connections between various Hindu deities are vividly showcased in the sculptural programs of numerous temples. While the main deity is naturally the focal point, a wide array of other gods and goddesses is also represented. These links are further evident in the formation of pantheons and the emergence of composite deities like Hari-Hara, who embodies both Vishnu and Shiva.

- One notable example of religious syncretism from this period is the incorporation of the Buddha into the list of Vishnu's avatars. However, there were limits to this accommodation, and relations between different religious communities were not always harmonious.

- For instance, although the Buddha is included in some Puranas as one of Vishnu's avatars, he is rarely depicted in Vishnu temples and never as the primary object of worship. Philosophical texts from this time reflect intense debates and contests, not only over doctrinal issues but also over patronage.

- The competitive relationship between various cults was sometimes expressed through iconic representations, such as the Devi trampling other Hindu gods or Buddhist deities overpowering Hindu ones, typically Shiva. Inscriptions from the period also highlight the interplay between different deities and their significance in religious practices.

- For instance, a donative inscription from Varahadeva, a minister of the Vakataka king Harishena, mentions Indra, Vishnu, Rama, Hara, and Kama in one of the Buddhist caves at Ajanta. Similarly, the Silappadikaram describes a Jaina arhat using epithets associated with Shiva and Brahma, showcasing the fluidity and interconnectedness of religious identities.

- The Badami caves, dating to the late 6th century, feature one of the earliest sculptural depictions of Hari-Hara, a composite deity representing both Vishnu and Shiva. In this depiction, Shiva occupies the right side, while Vishnu is on the left.

- The god is portrayed with four arms, each holding significant attributes: the rear right hand wields a battleaxe entwined with a snake (Shiva's attribute), the rear left hand holds a conch shell (Vishnu's symbol), and the front left hand is positioned in the katihasta gesture, resting on the thigh. The front right hand is broken, adding to the unique characteristics of this early representation of Hari-Hara.

- Hari-Hara is a deity that combines elements of both Vishnu (Hari) and Shiva (Hara). One of the earliest known sculptures of Hari-Hara can be found in the Badami caves, dating back to the late 6th century. In this depiction, Shiva is shown on the right side and Vishnu on the left.

- The god is depicted with four arms, each holding different objects that represent the attributes of Shiva and Vishnu.

- The right side of the crown features Shiva’s matted hair, while the left side displays Vishnu’s crown. The earrings also differ, with Shiva’s ear adorned with a snake-shaped earring and Vishnu’s ear with a makara-shaped earring.

- The panel also includes figures of Shiva’s entourage, some of whom are dancing while others play musical instruments.

- The major religious traditions interacted not only with each other but also with various local cults, beliefs, and practices. This is evidenced by the presence of stone and terracotta images of different deities, demi-gods, and demi-goddesses such as yakshas, yakshis, nagas, nagis, gandharvas, vidyadharas, and apsaras, indicating other areas of popular devotional worship.

- The independent worship of yakshas and nagas persisted during this period, with notable examples including a yaksha temple at Padmavati near Gwalior and a temple dedicated to the yaksha Maninaga at Rajgir.

- At Ajanta, a naga shrine is linked to Cave 16, while Cave 2 features a shrine dedicated to the yakshi Hariti and her consort Panchika.

- However, the large-scale sculptures of yakshas and nagas seen in earlier times declined, and these figures began to appear more frequently as dvarapalas (gatekeepers) of the major deities or as subsidiary figures.

- This shift reflects the efforts of the dominant religious traditions to establish connections with popular cults while also appropriating and subordinating them.

Rise of Donative Inscriptions and Sattras:

- During this period, donative inscriptions became more common, particularly those related to the maintenance of sattras or charitable feeding houses.

- These sattras were likely associated with religious establishments and played a role in providing meals to those in need.

- For example, a fragmentary stone inscription discovered at Gadhwa in the Allahabad district of Uttar Pradesh records a gift of 10 dinaras and another gift of uncertain value for the upkeep of a sattra.

- The donors mentioned in this inscription included individuals led by Matridasa and a woman from Pataliputra.

- Another inscription from Gadhwa, dated in Gupta year 98, documents a gift of 12 dinaras, presumably intended for the maintenance of a sattra.

Continuity of Vedic Rituals:

- Despite the growing popularity of devotional forms of religious practice, Vedic rituals remained an important basis for royal legitimation among many dynasties during this period.

- Kings such as Samudragupta, Kumaragupta, Vijayadevavarman of the Shalankayana dynasty, Dharasena of the Traikutaka dynasty, and Krishnavarman of the Kadamba dynasty claimed to have performed the ashvamedha, a royal horse sacrifice.

- The Vakataka king Pravarasena I was noted in inscriptions for performing multiple horse sacrifices, along with various other Vedic rituals such as the agnishtoma, aptoryama, ukthya, shodasin, brihaspatisava, and vajapeya.

- Inscriptions from the Bharashivas and Pallavas also highlighted their performances of various shrauta sacrifices.

- Yupa inscriptions, which are sacrificial posts, were also in use during this time.

- For instance, the Bihar stone pillar inscription refers to the establishment of a sacrificial post by the brother-in-law of a Gupta king.

Connection with Sectarian Cults:

- As kings maintained their links with the shrauta sacrificial tradition, they also aligned themselves with the increasingly popular sectarian cults.

- This is evident from the sectarian epithets used by the kings in inscriptions and their patronage of temples dedicated to specific deities.

- The inscriptions and temple patronage reflect the blending of traditional Vedic practices with emerging sectarian religious trends, showcasing the evolving religious landscape of the time.

Royal Patronage and Religious Practices

- Vedic Rituals: Despite the rise of devotional forms of religious practice, Vedic rituals remained a crucial aspect of royal legitimation. Kings from various dynasties, including Samudragupta, Kumaragupta, and others, claimed to have performed Vedic sacrifices like the ashvamedha.

- Vakataka Sacrifices: King Pravarasena I of the Vakataka dynasty is noted for performing multiple horse sacrifices and other Vedic rituals such as the agnishtoma and vajapeya.

- Inscriptions and Sacrifices: Inscriptions from the Bharashivas, Pallavas, and others highlight the performance of various shrauta sacrifices, indicating a strong connection to the shrauta sacrificial tradition.

- Sectarian Patronage: While maintaining ties to shrauta traditions, kings also embraced popular sectarian cults, evident from their sectarian epithets and temple patronage.

Royal Prashastis and Religious Toleration

- Diverse Beneficiaries: The varied invocations and religious imagery in royal prashastis (inscriptions praising kings) suggest that royal patronage was not limited to a single religious direction. This diversity is seen as a form of ‘religious toleration’ among ruling elites in ancient and early medieval India.

- Political Strategy: Dispersing patronage across a wide range of beneficiaries was a smart political move, allowing kings to forge ties and alliances with different social groups and religious communities. This approach was feasible in an environment where religious traditions and identities were not viewed as mutually exclusive or hostile.

The Emergence of Tantra

The Emergence of Tantra

The early history of Tantrism, including its timeline and place of origin, is challenging to reconstruct. Identifying a core set of Tantric ideas and practices is also difficult due to their diversity and the secrecy that has always surrounded them. However, some general features of Tantra can be noted:

- Energy: Tantra places a strong emphasis on energy and its significance in spiritual practices.

- Rituals and Yogic Practices: Rituals and various yogic practices are central to Tantric traditions.

- Deities: Tantrism often involves the worship of formidable deities associated with energy and transformation.

- Sexual Rites: Sexual rites and symbolism are also integral to certain Tantric practices.

- The impact of Tantra was felt not only in Shaiva and Shakta sects but also within the Buddhist tradition, although to a lesser extent in Jainism. While Hindu and Buddhist Tantra share some broad similarities, they also have significant philosophical differences.

- The Tantric path was traditionally regarded as a secretive one, passed down by preceptors to select initiates. It involved the cultivation of beliefs and practices aimed at attaining supernatural powers and a state of liberation. Early medieval Indian Tantra drew on various sources such as the Veda, Mimamsa, Sankhya, Yoga, and Vedanta, yet developed its own distinct characteristics.

- Evidence of the worship of Tantric deities dates back to the 5th century, and some texts may have been composed during this period. The early medieval period witnessed further development of Tantric cults and practices.

- In Tantra, the concept of Godhead involves the union of masculine and feminine aspects, with energy (shakti) being central to this view. Tantric practice, known as sadhana, often begins with initiation (diksha) into a sect, which includes the imparting of a secret mantra by the guru to the initiate.

- Mantras, bijas (syllables associated with deities), yantras (diagrams), mandalas, mudras (symbolic gestures), and Hathayoga postures are crucial elements of Tantric rituals. These practices aim to awaken the kundalini energy, coiled like a serpent in the body, and draw it upwards towards union with the supreme.

- Sexual symbolism and magic are also aspects of Tantra. The notion of puja (worship) in Tantra involves transforming the worshipper into the deity and is often associated with the five elements (panchatattva): alcohol, meat, fish, parched grain, and sexual intercourse.

- According to Tantra, the Godhead consists of a union between a masculine and feminine aspect. Here, energy, known as shakti, is viewed as feminine and plays a crucial role in the Tantric understanding of the universe and the path to liberation. Tantric practice, often referred to as sadhana, involves various rituals and techniques aimed at awakening the kundalini energy, which is believed to be coiled like a serpent within the body.

- Initiation into a Tantric sect, known as diksha, involves a ritual process where a guru imparts a secret mantra to the initiate. Mantras, which are prayers and formulas, along with bijas—syllables associated with different deities that are believed to possess mystic power—play a significant role in Tantric practices.

- Diagrams called yantras, mandalas, or chakras, along with symbolic gestures known as mudras, are also integral to rituals. Hathayoga postures and meditation (dhyana) are essential components of Tantric practice, all aimed at harnessing the kundalini energy and drawing it upwards towards union with the supreme consciousness.

- Sexual symbolism and magic are additional aspects of Tantric tradition. The concept of puja (worship) in Tantra involves transforming the worshipper into the deity, often associated with the five elements known as panchatattva, which include alcohol, meat, fish, parched grain, and sexual intercourse.

- Tantrism was divided into various sects, primarily focused on the worship of Vishnu, Shiva, and Shakti. Each sect had its own texts, with most being in Sanskrit. There was a close connection between the Shaiva and Shakta cults because Shiva and Shakti were considered closely related. The Pancharatra was the most significant early Tantric sect among the Vaishnavas. The Sahajiyas of Bengal emerged later as a sect within Tantric Vaishnavism. In the early medieval period, Shaiva Tantric sects such as the Kapalikas, Kalamukhas, and Nathas gained prominence. Besides small groups of Tantric practitioners, Tantrism had a broad impact on non-Tantric cults and traditions.

The Evolution of the Vaishnava Pantheon

- The worship of gods and goddesses that were eventually integrated into the Vaishnava pantheon was evident during the period of c. 200 BCE–300 CE. In the following centuries, this pantheon became more distinct. The cults of Narayana, Vasudeva Krishna, and Samkarshana Balarama were incorporated into the Vaishnava tradition, and Shri Lakshmi was acknowledged as the consort of Vishnu.

- However, despite the growing prominence of the Vishnu aspect, the cults of these deities maintained their unique identities. This is reflected in the fact that although the term ‘Vaishnava’ is frequently found in the Puranas, it is rare in the Mahabharata and not very common in inscriptions from this period. Instead, the term parama-bhagavata appears more often.

- The worship of gods and goddesses later integrated into the Vaishnava pantheon was evident between c. 200 BCE–300 CE. Over time, this pantheon became more distinct. The cults of Narayana, Vasudeva Krishna, and Samkarshana Balarama were incorporated into Vaishnavism, and Shri Lakshmi was acknowledged as Vishnu's consort.

- Even though the Vishnu aspect grew in importance, the individual identities of these cults remained. This is shown by the frequent use of 'Vaishnava' in the Puranas, its rarity in the Mahabharata, and its infrequent occurrence in inscriptions from this period, while the term 'parama-bhagavata' was commonly used.

- The worship of the avataras of Vishnu became increasingly popular. As mentioned in Chapter 8, the avataras eventually came to be conventionally reckoned as 10, but some of the names vary in different texts. The Matsya Purana lists 10 avataras. Three— Narayana, Narasimha, and Vamana— were divine, and seven—Dattatreya, Mandhatri, Rama (son of Jamadagni), Rama (son of Dasharatha), Vedavyasa, Buddha, and Kalki— were human.

- The Vayu Purana replaces the Buddha with Krishna. The Bhagavata Purana, which is a much later text (probably belonging to the 10th century), gives three different lists of the avataras.

- The assimilative potential of the avatara doctrine is indicated by the fact that some Puranas incorporate the Buddha in the list. The Bhagavata Purana does this, but changes the Buddha’s parentage—it describes him as the son of Ajana and states that he was born in Magadha. However, it should be noted that the Buddha incarnation was supposed to delude demons and lead them to hell.

- The garuda became the emblem of the Gupta emperors, and from the time of Chandragupta II, Gupta kings had the title parama-bhagavata in their inscriptions. The early Chalukyas adopted the boar as their emblem.

- Most Chalukya inscriptions—and those of their feudatories as well—start with an invocation to and praise of Vishnu’s boar incarnation. Some of the early Pallava and Ganga kings proclaimed themselves as worshippers of Vasudeva Krishna.

- Kings ruling in other parts of the country also described themselves as bhagavatas. Some inscriptions suggest that there was no contradiction between the worship of Vasudeva Krishna and the performance of Vedic sacrifices.

- The Brihatsamhita of Varahamihira states that the installation of an image of Vishnu should be performed by the bhagavatas according to their own rule, and that during such an installation, the twice-born priest should offer sacrifice into the fire with corresponding mantras.

- Lakshmi continued to be a prominent goddess associated with good fortune, including that of kings and cities, apart from being recognized as the consort of Vishnu. Her Gaja-Lakshmi form is depicted on many Gupta coins.

Emblems and Titles of Ancient Indian Rulers

The garuda, a mythical bird, became the symbol of the Gupta emperors. From the reign of Chandragupta II, Gupta kings began using the title parama-bhagavata in their inscriptions, indicating their devotion. The early Chalukyas chose the boar as their emblem, often starting their inscriptions with praises of Vishnu’s boar incarnation.

- Some early Pallava and Ganga kings identified themselves as worshippers of Vasudeva Krishna, and kings in other regions also referred to themselves as bhagavatas. Inscriptions suggest that worshipping Vasudeva Krishna and performing Vedic sacrifices were not contradictory.

- The Brihatsamhita by Varahamihira mentions that bhagavatas should install Vishnu’s image according to their customs, involving sacrifices by a priest during the installation. Lakshmi, known for bringing good fortune and as Vishnu’s consort, remained a significant goddess. Her Gaja-Lakshmi form is commonly found on Gupta coins.

Ahimsa (Non-Violence) in Vaishnava Traditions

- Ahimsa, or non-violence, was a crucial principle in early Vaishnava sects.

- The Narayaniya section of the Mahabharata describes a horse sacrifice performed by King Vasu Uparichara, a devotee of Vishnu, where no animals were harmed; only natural products were offered.

- The Vishnu Purana emphasizes that a true devotee of Vishnu refrains from any form of violence.

- This emphasis on ahimsa may have been influenced by the teachings of Buddhism and Jainism, which also advocate non-violence.

Early Pancharatra and Vaikhanasa Traditions

- Early Pancharatra and Vaikhanasa traditions were significant Vaishnava practices that blended devotion to Vishnu with ascetic and yogic elements.

- In these traditions, non-injury was a key aspect of ritual understanding.

- The Narayaniya Parva of the Mahabharata, though not exclusively a Pancharatra text, contains several concepts central to Pancharatra.

- It advocates for devotion to Narayana, also known as Vasudeva, Vishnu, and Hari, and emphasizes the importance of renunciation and non-injury in rituals, steering clear of animal sacrifices.

- The text also highlights yogic practices and introduces the idea of four emanations of Vishnu and the five observances of the day, known as panchakala.

- The four emanations, named after Vrishni heroes, are interpreted cosmologically: Vasudeva signifies supreme reality, Samkarshana represents matter (prakriti), Pradyumna stands for cosmic mind (manas), and Aniruddha symbolizes cosmic self-consciousness (ahamkara).

- Initially, the term murti was used for these emanations, while later texts adopted the term vyuha.

- The concept of panchakala in Pancharatra includes: abhigamana (approaching the deity, like morning prayers), upadana (rituals involving offerings), and other observances throughout the day.

Early Development of Vaishnavism

Pancharatra Tradition

- The early Pancharatra tradition emphasized devotion to Vishnu along with ascetic and yogic practices.

- Non-injury was a key aspect of Pancharatra rituals.

- The Narayaniya Parva of the Mahabharata, while not strictly a Pancharatra text, contains elements aligned with Pancharatra beliefs, advocating devotion to Narayana (Vasudeva, Vishnu, Hari).

Key Concepts in the Narayaniya Parva

- The text introduces the idea of four emanations of Vishnu named after Vrishni heroes: Vasudeva Krishna, Samkarshana, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha.

- These emanations are interpreted cosmologically: Vasudeva as supreme reality, Samkarshana as matter (prakriti), Pradyumna as cosmic mind (manas), and Aniruddha as cosmic self-consciousness (ahamkara).

- The term murti is used for these emanations in the Narayaniya Parva, while later texts use vyuha.

Panchakala Observances

- The concept of panchakala includes five daily observances: abhigamana (morning prayers), upadana (collection of worship materials), ijya (sacrifice or worship), svadhyaya (studying texts), and yoga (meditation).

Vaikhanasa Tradition

- The Vaikhanasa Shrautasutra and Smartasutra, composed between the 4th and 8th centuries, focus on devotion to Vishnu or Narayana.

- The Smartasutra discusses the installation of Vishnu images in homes, temples, or sacrificial arenas, accompanied by Vaishnava mantras.

- It also outlines disciplines and virtues for hermits devoted to Vishnu.

- Yoga is considered crucial in the stage of complete renunciation, aiming for union with the Supreme Self.

Iconography and Worship Practices

- Sculptures and inscriptions from this period depict various aspects of Vishnu’s mythology, including his association with the garuda, his role as the supporter of the three worlds, and his battles against demons like Madhu, Mura, and Punyajana.

- Vishnu is also shown bearing his divine weapons, such as the discus, club, bow, and the sword Nandaka.

- While multiple avataras of Vishnu were worshipped, four incarnations were particularly prominent: Varaha (boar), Narasimha (man-lion), Vamana (dwarf), and Manusha (Vasudeva Krishna).

- These avataras are frequently depicted in relief carvings on the walls of cave shrines and structural temples.

Early Medieval Period: Vaishnava Sculptures and Inscriptions

- Sculptures and inscriptions from this period depict various aspects of Vishnu's mythology, including his association with the garuda, his resting on the waters of the four oceans, and his role as the slayer of demons such as Madhu, Mura, and Punyajana.

- Vishnu is also shown as the bearer of the discus, club, bow made of horn, and the sword known as Nandaka.

- While there is evidence of the worship of various avataras of Vishnu, four incarnations were particularly prominent: Varaha (boar), Narasimha (man-lion), Vamana (dwarf), and Manusha, i.e., Vasudeva Krishna.

- These avataras are frequently depicted in relief carvings on the walls of cave shrines and structural temples.

Inscriptions and Patronage of Vaishnava Establishments

- Inscriptions reveal the wide-ranging sources of patronage for Vaishnava establishments across different regions in India.

- Gifts to temples dedicated to Vasudeva Krishna and Vishnuhave been found in various places, including:

- Tusham in Haryana

- Nagari in Rajasthan

- Bhitari and Gadhwa in Uttar Pradesh

- Eran, Mandasor, and Khoh in Madhya Pradesh

- The Mehrauli iron pillar inscription from the reign of Chandra mentions the establishment of a standard for Vishnu at a site called Vishnupada.

- An inscription in the Udayagiri caves near Vidisha, featuring panels of Vishnu and a goddess, likely dedicated by a local maharaja, possibly a vassal of Chandragupta II.

- A stone pillar inscription from the time of Skandagupta at Bhitari documents the installation of an image of Vishnu as Sharngin (the bow or horn called Sharnga) and the allocation of the village where the pillar is located.

- The Junagarh inscription from Skandagupta’s reign indicates that in Gupta year 138 (457–58 CE), Chakrapalita built a temple for Vishnu, known as Chakrabhrit (wielder of the chakra).

- The Eran inscription from the early rule of the Huna king Toramana mentions Dhanyavishnu, a notable from Airakina vishaya, who erected a shrine over a boar image, with the inscription carved on its chest.

Shaivism

- The worship of Shiva gained significant popularity during the period of 300–600 CE. During this time, Shiva became associated with other deities such as Ganesha, Karttikeya, and the river goddess Ganga.

- The Shaiva Puranas describe various forms of Shiva and the installation of Shiva lingas in temples, indicating the existence of different Shaiva sects. While these texts present Shiva’s worship as part of the mainstream smarta tradition, it is evident that some sects existed on the margins, and others, like the Tantric sects, were outside and condemned by Brahmanical texts.

- The Pashupatas and Shaiva Saiddhantikas viewed themselves as connected to the Vedic tradition, while the Kapalikas and Kalamukhas positioned themselves outside of it.

Pashupata Sect

- The Pashupatas are considered one of the oldest and most significant Shaiva sects. Their philosophy is based on the distinction between the individual soul ( pashu ), god ( pati ), and worldly fetters ( pasha ). Liberation is viewed as a state where the soul and Shiva are closely associated, achievable through the god’s grace.

- The Pashupatas are linked with yogic practices and are often depicted as ascetics with ashes ( bhasma ) smeared on their bodies. Sculptures and inscriptions indicate the Pashupata sect’s popularity in places like Mathura.

- The presence of Lakulisha, a significant figure associated with the Pashupata sect, in early temples like the Lakshmaneshvara, Bharateshvara, and Shatrughneshvara temples in Orissa, suggests the sect’s influence in the region.

Remains of Shiva Temples

- Remains of Shiva temples have been discovered at Bhumara and Khoh in central India. Sculptures and inscriptions suggest the existence of many more temples that have not survived.

- Shiva is mentioned and invoked in numerous inscriptions from this period. Some kings, such as the Maitrakas of Valabhi, referred to themselves as parama-maheshvara, meaning the supreme worshipper of Maheshvara, another name for Shiva.

- The Karamadanda inscription from the time of Kumaragupta I mentions the installation of a linga named Prithvishvara by a man named Prithivishena, a government official.

- An inscription on the back wall of one of the Udayagiri caves in Madhya Pradesh refers to the gift of the cave as a temple of Shambhu (another name for Shiva) by a minister named Virasena during a military expedition with Chandragupta II.

- The Mathura pillar inscription from Gupta year 61 records the building of a temple-cum-residence by a teacher named Uditacharya for his teacher and his teacher’s teacher, along with the installation of two Shaiva images. This practice of naming a Shiva linga or temple after preceptors or patrons was common during this period.

- The remains of Shiva temples have been discovered at Bhumara and Khoh in central India. Additionally, sculptures and inscriptions suggest the existence of many more temples that have not survived. Numerous inscriptions mention and invoke Shiva, and some kings, like the Maitrakas of Valabhi, referred to themselves as parama-maheshvara, meaning the supreme worshipper of Maheshvara, another name for Shiva.

- For instance, the Karamadanda inscription from the time of Kumaragupta I talks about the installation of a linga named Prithvishvara by Prithivishena, a mantrin and kumaramatya. An inscription in one of the Udayagiri caves in Madhya Pradesh mentions the cave being gifted as a temple of Shambhu (Shiva) by Virasena, a minister of Chandragupta II.

- The Mathura pillar inscription from the Gupta period records the building of a temple-residence by a teacher named Uditacharya for his teacher and his teacher’s teacher, along with the installation of two Shaiva images. This period saw the practice of naming Shiva lingas or temples after preceptors or patrons.

Mahadeva in the Elephanta cave

- The island of Elephanta, located off the coast of Mumbai, was named by the Portuguese after a large elephant sculpture that was once found there. The island is home to several caves, with Cave 1 being the most famous, dating back to the mid-6th century CE. This cave, measuring approximately 40 meters north to south, features a spacious pillared hall with a square shrine at the western end, housing a linga and yoni.

- The four entrances of the shrine are guarded by imposing dvarapalas, or doorkeepers. The walls of the large hall are adorned with niches that frame exquisite relief carvings, one of which depicts Lakulisha, indicating the caves' association with the Pashupata sect.

- The most remarkable carving in the hall is a relief of Maheshvara (Shiva), standing over 5 meters tall, with three faces. The faces in the center and to the right display a calm expression, while the left face appears angry, with bulging eyes. Some scholars suggest the implication of a fourth face at the back and possibly a fifth face on top, facing the ceiling, based on the description of Shiva's five faces in the Vishnudharmottara Purana.

- One interpretation of the three faces is that they represent Aghora-Bhairava (a fierce form of Shiva), Shiva himself, and Parvati. Stella Kramrisch, a scholar, identified the three faces as those of Shiva in his forms of Sadyojata, Aghora, and Vamadeva .

Maheshvara (Shiva)

The hall features an impressive relief carving of Maheshvara (Shiva) standing over 5 meters tall, depicting Shiva with three faces. The central and right faces display a serene expression, while the left face appears angry, with bulging eyes. Some scholars suggest the presence of a fourth face at the back and possibly a fifth face on top, facing the ceiling, based on descriptions from the Vishnudharmottara Purana. According to different interpretations:

- The three faces might represent Aghora-Bhairava (a fierce form of Shiva), Shiva, and Parvati.

- Stella Kramrisch identified the faces as Sadyojata, Aghora, and Vamadeva.

- Kramrisch's description of the sculpture is detailed and evocative, portraying Mahadeva as the fully manifest Supreme Shiva. The central face is Sadyojata, with Aghora and Vamadeva flanking it. The shoulders belong to the central face, and the chest appears smooth and youthful, suggesting a sense of breath and stillness.

- The necklace draped on the chest adds to the sculpture's elegance. The hands play a crucial role in conveying the identity and emotions of the faces. The right hand, though damaged, is raised, while the left hand rests on the base, holding a ripe fruit with the point facing up.

- The shoulders of the lateral faces are turned away from the viewer, and their hands rest on their backs. The left hand, belonging to the wrathful face, holds a serpent, while the right hand, associated with the blissful face, delicately holds a lotus flower on the shoulder. The overall composition of the sculpture creates a sense of harmony and balance, with the broad body filling the recess like an altar adorned with offerings.

- The frontal image of Mahadeva projects boldly, resembling a strong pillar with a serene expression and a radiant crown. The lateral heads mirror the ascent of the central figure, forming a strong triple arch that binds the three images together.

The Cult of the Great Goddess

The worship of Durga, as seen in the epics and Puranas, highlights her significance. In the Ramayana , Uma is depicted as the daughter of Himavat and the sister of Ganga. The Harivamsha refers to her as the sister of Vishnu and Indra, while she is also known in mythology as Ekanamsha or Bhadra, the sister of Vasudeva Krishna. In the Mahabharata , she is described as the wife of Narayana and Shiva, but over time, she became particularly associated with Shiva. Shiva and His Consort

- Shiva is called Girisha, the lord of the mountains. Uma, in turn, is known as Girija, Shailaputri, Uma Haimavati, and later, Parvati.

- Shiva, as Umapati, the husband of Uma, is closely linked to her various forms, such as Maheshvari, Ishani, Mahadevi, Mahakali, and Shivani.

Aspects of the Goddess

- In her destructive aspect, the goddess is known as Kali (Destruction), Karali (The Terrible), Bhima (the Frightful), and Chandi/Chandika/Chamunda (the Wrathful).

- The Markandeya Purana describes her as the destroyer of demons like Mahishasura, Raktavija, Shumbha, Nishumbha, Chanda, and Munda.

- Conversely, she also has a pacific aspect, exemplified by her manifestation as Sarasvati.

- The combination of benevolent and terrifying forms in both Shiva and Shakti likely facilitated the merging of their cults.

- In the Ramayana, Uma is described as the daughter of Himavat and the sister of the river Ganga. The Harivamsha refers to her as the sister of the gods Vishnu and Indra. She is also known in mythology as Ekanamsha or Bhadra, the sister of Vasudeva Krishna. The Mahabharata mentions her as the wife of the gods Narayana and Shiva. Over time, she became particularly associated with Shiva, who is known as Girisha, the lord of the mountains.

- Uma, in turn, is called Girija, Shailaputri, Uma Haimavati, and later Parvati. Shiva, as her husband, is known as Umapati, and she is revered as Maheshvari, Ishani, Mahadevi, Mahakali, and Shivani.

- The different names of the goddess reflect her various aspects and personalities. In her destructive aspect, she is known as Kali (Goddess of Destruction), Karali (the Terrible), Bhima (the Frightful), and Chandi, Chandika, or Chamunda (the Wrathful). The Markandeya Purana describes her as the destroyer of many demons, including Mahishasura, Raktavija, Shumbha, Nishumbha, Chanda, and Munda.

- On the other hand, she also has a pacific aspect, as seen in her manifestation as Sarasvati, the goddess of knowledge and wisdom. The combination of both benevolent and terrifying forms in Shiva and Shakti likely contributed to the merging of their cults.

- The epic-Puranic tradition is full of stories showcasing the close relationship between Shivaism and Shaktism. The Mahabharata mentions three Shakta pithas, which are sacred places associated with the goddess Shakti. These pithas are linked to the story of Sati, whose dismembered body Shiva carried away after her death. Legends tell of Sati's resurrection as Uma and the rigorous penances she undertook to reunite with her husband.

- There are also tales of the marriage of Shiva and Parvati, their harmonious life on mount Kailasha, and the dire consequences faced by those who disturb their union. Over the centuries, artisans have enjoyed depicting this divine couple on temple walls, capturing their majestic and loving relationship.

- The Shakti cult was particularly popular in eastern India, but its influence extended beyond this region, as evidenced by the numerous Durga images found across the country. These images can be categorized into two types: ugra (fierce) and saumya (pacific). One of the most popular depictions is that of Durga Mahishasura-mardini, showcasing the goddess in her fierce aspect as she battles the buffalo demon Mahishasura.

The Shakti Cult and Its Spread

The Shakti cult, which focused on the worship of the goddess Durga, was particularly popular in eastern India. However, it was not limited to this region, as evidenced by the numerous Durga images found across different parts of the country. These images can be classified into two categories: ugra (fierce) and saumya (pacific).

- Ugra (Fierce) : This category depicts Durga in her fierce aspect, showcasing her as a powerful warrior goddess. The most famous representation of this aspect is Durga Mahishasura-mardini, where she is portrayed slaying the buffalo demon, Mahishasura. Many such images have been discovered from ancient times, especially in central India. For instance, a relief of Durga Mahishasura-mardini is carved outside Cave 6 at Udayagiri in Madhya Pradesh.

- Saumya (Pacific) : In this category, Durga is depicted as a more peaceful and benevolent figure. She is often shown as a nurturing mother, embodying qualities of compassion and care.

- Maternal Aspect : Durga was also revered for her maternal qualities. She is considered the mother of Karttikeya (the god of war) and Ganesha (the remover of obstacles). Additionally, Durga was worshipped as one of the Sapta-Matrikas or Seven Mothers, who are believed to be the energies of various gods assisting the Devi in her battles against demons.

- The Seven Mothers : Brahmani, Maheshvari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Indrani, and Yami (Chamunda).

- Inscriptional References : Historical inscriptions mention the building of a temple dedicated to the Matrikas by Kumaraksha, a minister of Vishvavarman, ruler of Dashapura. The Bihar stone inscription also references Skanda (Karttikeya) and the divine mothers.

- Relief Sculptures : Relief sculptures depicting the Matrikas in association with Shiva have been found at various sites, including Badoh-Pathari, near Besnagar. A damaged group of Matrika sculptures, possibly from Besnagar, is housed in the Gwalior Archaeological Museum. Matrika figures have also been discovered at Shamalaji in Gujarat.

- Gupta Coins : Some Gupta coins feature a female figure associated with a lion, which is believed to represent Durga.

The Worship of Other Deities

Worship of Other Deities

Brahma

- Brahma is praised in the Brahma Purana, and guidelines for making his images are found in texts like the Brihatsamhita and Vishnudharmottara Purana.

- Sculptures of Brahma, though not as common as those of other deities, have been discovered in various places.

- He is typically depicted with three faces, a potbellied body, and four arms. His hands usually hold a shruk (large wooden ladle), shruva (small wooden ladle), akshamala (string of beads), and pustaka (book). His vehicle is the hamsa (goose).

- Despite being part of the Puranic trinity and associated with sacred sites like Prayaga and Pushkara, Brahma never attained the same level of worship as Shiva, Vishnu, or Durga.

- Over time, he became a subsidiary deity, with his images placed in niches of temples dedicated to other gods.

Surya

- The Bhavishya, Shamba, and Varaha Puranas detail the origins of Surya worship, including the associated priests and festivals.

- The Kurma Purana advises kings to worship Vishnu and Indra, and emphasizes that Brahmanas should particularly honor Agni, Aditya (Surya), Brahma, and Shiva.

- The Surya-hridaya hymn within the Kurma Purana extols Surya as the supreme god, encompassing all other deities.

- Priests of solar temples, known as Bhojakas, Magas, and Somakas, played a significant role in Surya worship, particularly the Brahmanas of Shakadvipa.

- The Magas, possibly of Iranian origin, were known for their fire and sun worship.

- The early iconography of Surya images reflects Western influence, with depictions of a cylindrical headdress, a long coat with a waist scarf, holding lotus buds, and wearing boots. Surya is also frequently shown with a horse-drawn chariot.

Surya

The Bhavishya, Shamba, Varaha, and other Puranas detail the beginnings of Surya worship, including the priests and festivals linked to it. The Kurma Purana advises kings to worship Vishnu and Indra, while Brahmanas should particularly honor Agni, Aditya (Surya), Brahma, and Shiva. It features the Surya-hridaya hymn, which lauds Surya as the supreme god encompassing all other deities.

- Priests and Worship: The priests associated with solar temples are known as Bhojakas, Magas, and Somakas. The Brahmanas of Shakadvipa had a special connection with Surya worship. The Magas, likely of Iranian descent, worshipped fire and the sun, indicating a blend of cultural influences.

- Iconography and Western Influence: Early images of Surya show Western influence, especially in the iconography. Northern images from this period, like those in the Shiva temple at Bhumara, depict Surya with distinct features such as a high cylindrical headdress, a long coat, and boots, often associated with a horse-drawn chariot.

Remains and Patronage of Surya Temples: Remains of Surya temples have been discovered in western India, particularly in Gujarat. There is also evidence of patronage for Surya temples in places like Gwalior, Indore, and Ashramaka in central India.

- For instance, the Mandasor inscription mentions the construction and renovation of a Surya temple at Dashapura by a guild of silk weavers.

- An Indore copper plate from the reign of Skandagupta records a grant for maintaining a lamp in a Surya temple.

- Maharaja Sarvvanaga of Uchchhakalpa made a gift for a Surya temple in Ashramaka, and a Gwalior inscription from the time of Mihirakula notes the construction of a temple dedicated to Surya.

- Surya Images and Regional Worship: Surya images have been found in Bengal, and the sun god Chitraratha was a tutelary deity of the Shalankayana dynasty in the Andhra region. The worship of Surya and related deities highlights the regional variations and the significance of solar worship in ancient India.

Karttikeya

- Early Representations and Popularity: The earliest images of Karttikeya are found on punch-marked coins from earlier centuries. He was widely worshipped during the period of c. 300–600 CE and was later integrated into the Shiva family as one of Shiva's sons.

- Inscriptions and Royal Patronage: The Bilsad stone pillar inscription from Uttar Pradesh mentions the construction of a gateway, a sattra (a type of religious institution), and the erection of a column at a temple dedicated to Mahasena (Karttikeya) by Dhruvasharman. The Kadamba dynasty also revered Karttikeya, and Emperor Kumaragupta I of the Gupta dynasty used the peacock, Karttikeya's vehicle, as his emblem.

- Icons and Depictions: In northern India, Karttikeya is typically depicted as two-armed, riding a peacock, and wielding a spear. He is sometimes shown with his wives, Devasena and Valli. A notable relief of Karttikeya can be seen in Cave 3 at Udayagiri.

- Regional Worship: In South India, Karttikeya is known as Subrahmanya. His worship was prevalent across different regions, reflecting the deity's widespread significance and the variations in his portrayal and attributes.

Karttikeya

- Earliest representations on punch-marked coins.

- Popular worship c. 300–600 CE, later absorbed as Shiva's son.

- Bilsad Stone Pillar Inscription : Records a gateway, steps, and a column at Mahasena (Karttikeya) temple, built by Dhruvasharman.

- Kadamba dynasty kings were devotees.

- Gupta emperor Kumaragupta I used the peacock (Karttikeya's vehicle) as his symbol.

- Worshipped in South India as Subrahmanya.