Cities, Kings, and Renunciants - 2 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| The Persian and Macedonian Invasions |

|

| Atranjikhera: From Village to Town |

|

| Shravasti: Excavated Monasteries and Mound |

|

| Early Urban Development in Central India and the Deccan |

|

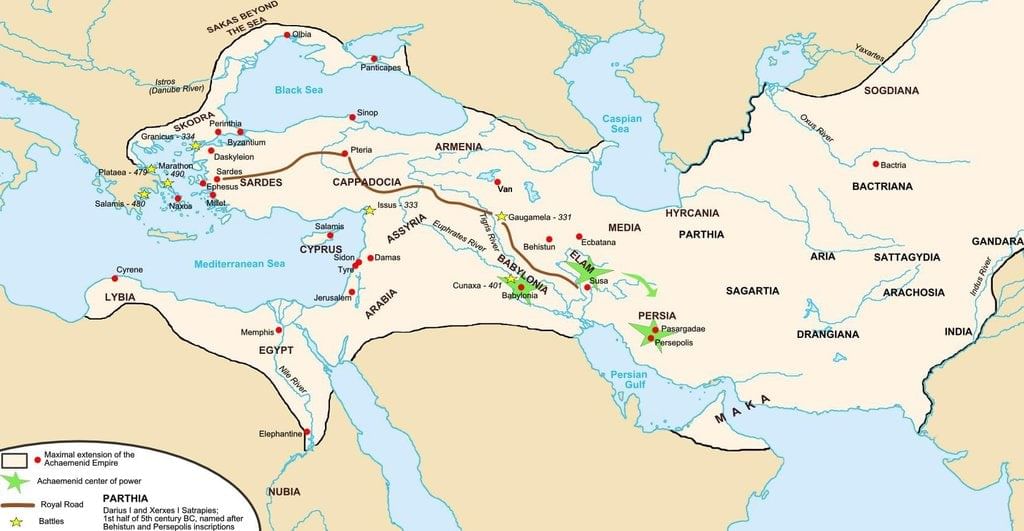

The Persian and Macedonian Invasions

In the 6th century BCE, the Persian Empire expanded to the northwestern borders of the Indian subcontinent. King Cyrus of the Achaemenid dynasty led a military campaign that resulted in the destruction of the city of Kapisha, located southeast of the Hindu Kush mountains.

- The Greek historian Herodotus recorded that the Indus Valley, referred to as "India," was the most prosperous province (satrapy) of the Persian Empire, receiving a tribute of 360 talents of gold dust, surpassing all other provinces combined.

- Inscriptions from Darius I's reign mention various peoples under Persian rule, including the Gandharans and the Hindus of the lower Indus Valley. Darius is also credited with sending an exploratory fleet down the Indus River.

- Darius was succeeded by Xerxes, who maintained control over regions like Gandhara and the Indus Valley. Despite the decline of the Persian Empire after Xerxes, these regions remained under Persian influence for some time.

- The most significant Persian impact on India was the introduction of the Kharoshthi script, derived from Aramaic, the official script of the Persian Empire. Some historians suggest Persian influence on Mauryan administration and art, though this is debated.

- By the time of Alexander's invasion in 327–326 BCE, Persian control over these regions was likely weakened. Alexander established outposts in Afghanistan and encountered various principalities in the northwest Indian subcontinent. Greek historians provide detailed accounts of Alexander's campaigns, including his sieges of strongholds like Aornos, which was reputedly difficult to conquer.

Alexander's Conquest and Retreat

In 326 BCE, Alexander's army crossed the Indus River into the Indian subcontinent. Initially, he received support from Ambhi, the ruler of Taxila. However, he faced resistance from Porus, who ruled the region between the Jhelum and Chenab rivers. Despite Porus's efforts, Alexander was able to overpower him.

- After defeating Porus, Alexander continued his campaign, capturing the territory between the Chenab and Ravi rivers. However, his troops, exhausted from years of fighting and eager to return home, refused to march further east beyond the Beas River. This forced Alexander to retreat to the Jhelum River and begin his journey back towards the Indus delta.

- During his retreat, Alexander left the recently conquered territories in the hands of local rulers like Porus, Ambhi, and Abhisara. He entrusted the areas west of Punjab to Macedonian governors and garrisons. Along the way, he encountered military resistance from various groups, including the Malloi, Oxydrakai, Sibae, and Agalassoi. After reaching the Indus delta, Alexander took the land route through Gedrosia towards Babylon, where he died two years later.

Impact of Alexander's Invasion

- Alexander's invasion is typically viewed as a brief incursion into the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent, with no significant or lasting impact.

- However, it did lead to the establishment of a Seleucid principality in the north-west and the creation of several Greek settlements in the region, such as Boukephala, Nikaia, and various Alexandrias.

- Recent studies have re-evaluated the historical accounts of Alexander's invasion, questioning both the legendary status of Alexander and the way history has been written about this period.

- It has been suggested that the Greek presence in and around the Indian subcontinent should be understood in the context of broader trade and cultural interactions involving India, the Persian Gulf, and the Mediterranean.

- This perspective encourages a review of classical historical accounts alongside archaeological findings, inscriptions, and coinage evidence.

The Storming of the Malloi Citadel

- Greek historians have provided detailed accounts of Alexander's life and military career, particularly Arrian in his work "Anabasis of Alexander." Written in the 1st-2nd century CE, Arrian's account relies on earlier writings by Aristobulus of Cassandreia and Ptolemy, son of Lagus, both of whom accompanied Alexander on his campaigns. Arrian's description of the storming of the Malloi citadel is a notable part of this narrative.

- When it was observed that the citadel was still under the army's control, with many soldiers positioned in front as if to fend off attacks, some Macedonians attempted to breach the wall by undermining it or by placing scaling ladders against it where possible. Alexander, noticing that the men carrying the ladders were too slow, took matters into his own hands. He grabbed a ladder from one of the soldiers, set it against the wall himself, and began to climb, crouching under his shield.

- Following Alexander, Peucestas, who carried the sacred shield taken from the temple of the Trojan Athena, climbed the ladder. He was followed by Leonnatus, a trusted bodyguard, and Abreas, a soldier recognized for his distinguished service. As Alexander approached the battlement, he leaned his shield against the wall and began pushing some of the Indians inside the fort while killing others with his sword. The shield-bearing guards, worried for the king's safety, rushed up the same ladder, causing it to break. Those already on the wall fell, making it impossible for the others to ascend. Now standing on the wall, Alexander was attacked from all sides by soldiers in the adjacent towers and by men in the city throwing darts at him from a nearby mound. Despite the danger, Alexander stood out for his impressive weapons and remarkable bravery. He realized that staying where he was would only put him in danger without achieving anything noteworthy. However, if he jumped down into the fort, he might intimidate the Indians. Even if he didn't, he would die doing something heroic that people would remember. With this resolve, he leapt down from the wall into the citadel.

Land and Agrarian Expansion

Literary evidence and findings from early NBPW sites indicate a growth in the number and size of village settlements, along with population increase in the Ganga valley during the period of around 600–300 BCE.

For example, a study by Makkhan Lal in 1984 on the Kanpur district revealed 99 NBPW sites, in contrast to 46 PGW and 9 BRW sites.

Establishment of Rural Settlements

- Early Buddhist texts provide insight into various types of rural settlements. The Vinaya Pitaka indicates that a village could consist of one to four kutis, which likely referred to a hamlet with a large house surrounded by smaller ones.

- The term gama (Pali for grama) could denote a hamlet, village, part of a settlement, temporary encampment, or even a group of traders settling in one place for an extended period.

Pali texts mention specific gamas associated with different professions, such as:

- Aramika-gama: Gamas of park attendants.

- Vaddhaki-gama: Gamas of carpenters.

- Nalakara-gama: Gamas of reed makers.

- Lonakara-gama: Gamas of salt makers.

- Brahmanas: Gamas of Brahmanas.

- Chandalas: Gamas of Chandalas.

Terms like gama-gamani and gamika referred to village headmen and overseers.

Agricultural Economy

- The foundation of the agricultural economy in various regions was established in earlier centuries. The significance of agriculture in the Ganga valley is evident from the numerous agricultural similes used in Buddhist texts. Several Vinaya rules were reportedly made in response to the needs of farmers. For example, the rule requiring monks to stay in one place during the monsoon was introduced because farmers complained to the Buddha about monks walking through their fields and damaging seedlings during the rainy season.

- In addition to agriculture, animal rearing, particularly cattle rearing, was practiced. However, land had clearly become the most crucial basis and form of wealth. The rise of urban centers indicates increasing agricultural yields and surpluses. Rice cultivation remained a vital aspect of agriculture in the Ganga valley.

Role of Iron in Agriculture

- The role of iron in agricultural expansion, the generation of surplus, and the emergence of urban centers has been a topic of debate among historians and archaeologists. Iron technology was one of several factors contributing to historical change in the 1st millennium BCE. By this time, iron was undoubtedly being used in agriculture in the Ganga valley.

- There was a noticeable increase in the number and variety of iron artifacts during the NBPW period compared to the earlier PGW phase.

Landholdings and Agricultural Practices

- Landholdings varied in size, with small farmers likely relying on household labor to cultivate their modest plots. In contrast, there were also large landowners, such as the Brahmana Kasibharadvaja of Ekanala village, who is said to have employed 500 ploughs on his land. References to Brahmana gamas in Magadha and Kosala indicate that Brahmanas were dominant landowners in these regions. Some of these villages may have been characterized by significant landholdings and agricultural activity.

- Initially, the land in question was known as brahmadeyas, which were parcels of land given by kings to Brahmanas as a mark of respect and gratitude. There is a specific instance in the Samyutta Nikaya where the Buddha is depicted as being denied food during his alms rounds in a place called Brahmana gama of Panchasala.

Private Property and Land Ownership

- The concept of private property in land is reflected in the mentions of land being gifted and sold. For instance, Anathapindika, a prosperous gahapati from Shravasti, purchased Jetavana from Prince Jeta Kumara with the intention of donating it to the sangha.

- Land given to the sangha was typically orchard or wooded land. The Vinaya Pitaka describes an arama (land donated to the sangha) as a flower garden (puppharamo ) or orchard (phalaramo ).

- The Anguttara Nikaya explicitly forbids the sangha from owning agricultural land. The Agganna Sutta in the Digha Nikaya links the emergence of kingship to conflicts over rice fields.

Kingship and Control over Land

- References in the Digha and Majjhima Nikayas to kings Bimbisara and Pasenadi granting land to Brahmanas and the sangha suggest that these kings had authority over certain land areas.

- It is likely that wastelands, forests, and mines also fell under their control. From the state’s perspective, land was a crucial source of revenue.

- Taxes on Land : Land taxes varied significantly, with Dharmashastra texts typically indicating the king’s share as one-sixth of the produce. The Gautama Dharmasutra specifies that cultivators might pay one-tenth, one-eighth, or one-sixth of their produce as tax.

Labour and Wage System

- Buddhist texts mention various types of workers such as dasas (male slaves), dasis (female slaves), kammakaras (wage labourers), and porisas (labourers).

- The term kammakara is relatively new and denotes someone who offers their labour for wages. The need for wage labour likely arose due to the insufficient household labour available to large landowners.

- The compound term dasa-kammakara is also used to refer to labourers. The Ashtadhyayi mentions vetan (wage) and vaitanika (wage earner), further emphasizing the wage labour system.

Atranjikhera: From Village to Town

Archaeological excavations at Atranjikhera, located in the Etah district of Uttar Pradesh along the banks of the Kali Nadi river (a tributary of the Ganga), have shed light on the transition from village life to urban settlement and the daily activities of the people during this period. The site revealed a overlap between the Painted Grey Ware (PGW) phase and the subsequent Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) phase.

The excavators identified four phases within the NBPW deposit, which was approximately 5 meters thick. Based on radiocarbon dating, the thickness of the deposits, and comparisons with other NBPW sites, these phases were dated as follows:

- Period IVA: circa 600–500 BCE

- Period IVB: circa 500–350 BCE

- Period IVC: circa 350–200 BCE

- Period IVD: circa 200–50 BCE

This discussion will focus on the initial two sub-periods, Periods IVA and IVB.

Transition in Pottery:

- During the early part of Period IV, there was a gradual shift from PGW pottery to NBPW pottery.

- Period IVA: NBPW pottery featured a fine grey inner surface with varying outer finishes, including shades of grey, brown, and black.

- Period IVB: Increased variety in pottery shapes and finishes, with some pots exhibiting silver or golden hues.

Settlement Expansion and Urbanization:

- The size of the settlement expanded significantly, indicating the early stages of urbanization.

- There was a noticeable transition from mud houses to more durable structures made of mud-brick and burnt brick.

Artifacts and Evidence of Daily Life:

- Excavations revealed a range of artifacts, including mud house floors, domestic hearths, cooking pots, and fire pits.

- Evidence of iron smelting was found, including iron slag and metal tools like arrowheads and spearheads.

- Artifacts included terracotta figures, beads, tools made of bone and ivory, and stone objects such as pestles and grinders.

Period IVB Developments:

- Evidence of flooding during this period led to the construction of protective mud bunds around the settlement.

- Continued development of infrastructure, including mud-brick walls and drainage systems.

- Discovery of terracotta figurines, game pieces, and ritualistic objects indicating cultural practices.

Continuity and Change:

- Some artifacts, such as beads made from semi-precious stones, showed continuity from the earlier PGW phase, while new designs and shapes emerged.

- The transition from mud to more durable building materials became more pronounced in the later NBPW phases.

Iron Objects at Atranjikhera during Period IV (NBPW Phase)

The NBPW phase at Atranjikhera yielded a significant number of iron and copper objects, indicating a diverse range of activities and crafts.

- Copper Objects: A total of 38 copper objects were found, with varying quantities from different phases of the NBPW level. These included antimony rods, nail parers, rods/bars, pins, bangles, an ear ornament, bead, socket, weight, and tubes, along with some indeterminate objects.

- Iron Objects: A total of 338 iron objects were discovered, including 37 indeterminate pieces. Many types from Period III continued, but 16 new artefact types emerged. Notably, agricultural tools made of iron appeared for the first time, along with iron plumb bobs used for wall alignment, iron weapons suggesting hunting or warfare, and tools indicating the importance of blacksmithing and carpentry.

- Coins: Two coins were found, one a silver punch-marked coin with various symbols and the other an uninscribed copper coin with distinctive designs.

The analysis of plant remains by S. K. Chowdhury revealed the following:

- OCP and BRW Phases: Limited remains of rice, barley, gram, and khesari.

- PGW Level: Evidence of wheat with indications of increased grain production.

- NBPW Phase: Cultivation of rice, wheat, barley, and the introduction of a new pulse, Phaseolus mungo. Wood remains included laurel, farash, bamboo, deodar, and Himalayan cypress, suggesting contact with northern regions.

Bone Fragment Analysis:

- Almost a thousand bone fragments were analysed, revealing remains of domesticated animals such as humped cattle, buffalo, goat, sheep, pig, and dog from the NBPW phase. Horse remains were found in the PGW and post-PGW phases.

- Bones were often split or cut with sharp tools and charred, indicating these animals were killed for food. Cattle bones were the most numerous, suggesting beef was a significant part of the diet, along with other meats.

The Northern Subcontinent: The Emergence of Urbanism and Political Authority (c. 600 BCE to c. 300 BCE)

The period witnessed a transformation in the nature of political authority and urbanization in the northern subcontinent. The historical and archaeological records indicate a shift from earlier forms of governance to more centralized and complex political structures. The emergence of urban centers during this period was not merely a reflection of increased population density but also indicative of enhanced administrative capabilities and socio-economic stratification.

- Archaeological evidence suggests that these urban centers were characterized by distinct architectural styles, urban planning, and a range of socio-economic activities. The presence of craft specialization, trade networks, and administrative infrastructure points to a significant level of social organization and economic complexity.

- The transition to urbanism in the northern subcontinent was likely facilitated by various factors, including agricultural surplus, technological advancements, and the establishment of trade links. This period laid the groundwork for the subsequent historical developments in the region, setting the stage for the emergence of more complex political entities and urban agglomerations in the later centuries.

- During the early centuries CE, the northern subcontinent saw the consolidation of urban centers that had emerged in the preceding period. These cities became hubs of political power, economic activity, and cultural exchange. The historical narratives and archaeological findings from this period reflect a continuation and expansion of the trends established earlier, with cities becoming increasingly important in the socio-political landscape of the region.

- The evolution of political authority during the early centuries CE was marked by the rise of various dynasties and regional powers that exerted control over significant territories. The inscriptions, coins, and other archaeological artifacts from this period provide insights into the nature of governance, administrative practices, and the relationships between different political entities.

- The period also witnessed the diversification of urban functions, with cities serving not only as political and administrative centers but also as focal points for trade, craft production, and cultural activities. The interactions between urban and rural areas became more pronounced, with rural hinterlands supplying resources and agricultural produce to support the growing urban populations.

- Overall, the early centuries CE in the northern subcontinent were characterized by the consolidation and expansion of urban centers, the diversification of urban functions, and the establishment of more complex and centralized forms of political authority. These developments laid the foundation for the subsequent historical trajectories of the region, influencing the dynamics of power, economy, and society in the following centuries.

The Northern subcontinent witnessed the emergence of urban centers and complex political authority, likely fueled by agricultural surplus and trade.

The Northern Subcontinent: Political Authority and Urban Centers (c. 600 BCE to c. 300 BCE)

During this period, the northern subcontinent saw the rise of urban centers and complex political authority, likely driven by agricultural surplus and trade. These urban centers became hubs of economic activity and political power, reflecting a significant shift in social organization. The period also marked the transition from earlier forms of governance to more centralized political structures, setting the stage for the subsequent historical developments in the region.

- In the early centuries CE, the northern subcontinent experienced the consolidation of urban centers that had begun to emerge earlier. These cities became increasingly important as centers of political power, economic activity, and cultural exchange. The period witnessed the rise of various dynasties and regional powers that exerted control over significant territories, with urban centers playing a crucial role in administration and governance. The interaction between urban and rural areas became more pronounced, with rural hinterlands supporting the growing urban populations.

- Assemblies and Councils: The tokens indicate the presence of local assemblies or councils involved in decision-making processes, likely related to land management, resource allocation, or community affairs.

- Diverse Settlements: The findings suggest a variety of settlement types within the region, each potentially serving different functions, from agricultural production to craft specialization.

- Social Stratification: The range of tokens and seals may reflect varying levels of social stratification, with some settlements likely having more complex social hierarchies than others.

The Northern Subcontinent: Political Authority and Urban Centers (c. 600 BCE to c. 300 BCE)

- The northern subcontinent during this period witnessed the emergence of urban centers and complex political authority, likely driven by agricultural surplus and trade. These urban centers became hubs of economic activity and political power, reflecting a significant shift in social organization. The period also marked the transition from earlier forms of governance to more centralized political structures, setting the stage for subsequent historical developments in the region.

- In the early centuries CE, the northern subcontinent experienced the consolidation of urban centers that had begun to emerge earlier. Cities became increasingly important as centers of political power, economic activity, and cultural exchange. The rise of various dynasties and regional powers exerted control over significant territories, with urban centers playing crucial roles in administration and governance. The interaction between urban and rural areas became more pronounced, with rural hinterlands supporting growing urban populations.

- During this period, the tokens suggest the presence of local assemblies or councils involved in decision-making processes, reflecting diverse settlement types within the region. Social stratification may have varied among settlements, with some exhibiting more complex social hierarchies than others.

- In the Vedas, the terms grama (village) and aranya (forest) are used to describe two contrasting spaces. The grama was seen as orderly and familiar, while the aranya was perceived as disorderly and unknown. The people living in these areas were also viewed differently, with forest dwellers being considered wild and strange. As urbanization progressed, forest people were increasingly depicted as culturally and socially backward.

- In epic texts like the Mahabharata and Ramayana, the forest is portrayed as a place of exile for the main characters. While there is some recognition and empathy for the forest, the distinction between grama and aranya is maintained. The heroes and heroines in exile are depicted differently from regular forest dwellers, who are shown hunting wild animals and gathering fruits and roots. There are also dramatic accounts of forest destruction, such as Dushyanta’s hunt in the Mahabharata, which involved the mass killing of animals and trees, and the burning of the Khandava forest by Krishna and Arjuna to clear land for the Pandava capital, Indraprastha.

- Such narratives reflect the idea of taming and conquering the forest.

- Some epic myths express disdain for forest dwellers. For example, in the story of Prithu, the first righteous king, his predecessor Vena is killed by Brahmanas for his wickedness. They churn Vena’s body, and from his left thigh emerges a short, dark man called Nishada, who is sent to the forest. From Vena’s right arm comes Prithu, a tall, fair, and handsome king.

- The forest is also depicted as a place of sages and ascetics, with certain Sanskrit texts romanticizing life in hermitages. In Kalidasa’s Shakuntala, for instance, the protagonist Shakuntala shares a close and loving bond with the forest’s plants and animals.

- Over time, encroachments on forests have increased, especially in modern times. Despite the gradual disappearance of forests, their influence remains through traditions like tree worship, which is often associated with fertility cults. This practice has persisted in various forms of popular religious observance in both urban and rural settings throughout the centuries.

Archaeological and Literary Profiles of Early Historical Cities

- There is less archaeological data available for early historical cities compared to the protohistoric Harappan sites.

- Many regions, including Kashmir, Punjab, Sindh, and the Northeastern states, have not been thoroughly explored for archaeological evidence.

- While some sites like Taxila and Bhita have seen large-scale excavations, most early historical urban sites were continuously occupied over many centuries, making it challenging to study their earliest layers.

- Some sites are still occupied today, further complicating archaeological research.

- The published details of smaller-scale excavations are often incomplete and inadequate, with few radiocarbon dates available to provide chronological context.

- Many archaeological reports do not differentiate between the early, middle, and late phases of the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) period, offering a consolidated view of approximately 700–100 BCE and providing less information on the earlier phases within this timeframe.

- Despite the gaps in knowledge about early historical urbanism, the new urban morphology is evident from both textual and archaeological evidence.

- While many major cities mentioned in historical texts have been identified through archaeology, some remain unidentified.

- Archaeological findings often confirm the significance of the great cities described in literature, although the details may not align perfectly due to inadequate excavations, incomplete reports, and embellishments in the literary tradition.

- The profiles of early historical cities can be reconstructed by combining available literary and archaeological evidence.

- These cities were interconnected through the trade routes of the time, highlighting their role as political, social, and economic spaces.

- Literature from this period presents varying views of the city, sometimes depicting it as an idealized space with a central king, while other texts emphasize the diverse and heterogeneous nature of cities as "points of convergence."

- Overall, the texts from this period vividly illustrate the concept of "citiness," reflecting different regional and temporal understandings of urban life.

The North-West

- Charsada and Taxila were the two major cities in the north-west, set at key points where trade routes crossed the Hindu Kush mountains. Besides the famous Khyber Pass, there were other important routes, including one through the Kabul Valley. A significant path connected Taxila to Kashmir and further into Central Asia. In the 5th century BCE, part of the north-west came under Achaemenid control and was later encountered by Alexander the Great.

- Charsada is the site of the ancient city of Pushkalavati, believed to have been founded by Pushkara, the son of Bharata, who was the brother of Rama. This city is referred to as Peucelaotis and Proclais in ancient texts. Historian Arrian noted that the people of Charsada resisted Alexander, leading to a Macedonian garrison being stationed there after Hephaestion quelled the uprising. Archaeological digs at the Bala Hisar mound in Charsada show continuous habitation from around 600 BCE, with the city being fortified by a ditch and mud rampart by the early 4th century BCE.

- Ancient Taxila was a crucial city linked to overland routes into Afghanistan and Central Asia, as well as maritime routes via the Indus River to the Arabian Sea. According to epic legends, this is where King Janamejaya conducted his famous snake sacrifice. Taxila is noted in various Buddhist, Jaina, and Greek texts. Extensive archaeological work at Taxila uncovered three major sites: Bhir mound, Sirkap, and Sirsukh. The Bhir mound is the site of the oldest settlement, with layers of occupation dating from the 6th/5th century BCE to the 2nd century BCE. The earliest layers of this mound (Period IV) revealed a burnished red ware known from an earlier period in the region, along with a new fine grey or black ware resembling local imitations of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW). Silver punch-marked bar coins and other coin types were also discovered, with more information available about the post-3rd century BCE levels at the Bhir mound.

The Indo-Gangetic Divide, Upper Ganga Valley, and Doab

In the Kumaon region of Uttarakhand, NBPW was discovered at Kashipur in Nainital district, although detailed information is scarce. Moving to the Indo-Gangetic divide, Period III at Ropar, located at the foothills of the Shivaliks, unearthed NBPW dating back to around 600–200 BCE. Similar pottery has been found at Agroha in Hissar district and at Karna-ka-Qila near Kurukshetra in Haryana.

- Excavations at the Purana Qila in Delhi, traditionally linked to Indraprastha from the Mahabharata, revealed NBPW layers dating to the 4th–3rd centuries BCE. The inhabitants lived in mud-brick and burnt brick houses, with findings including a burnt wattle-and-daub structure and multiple hearths. The houses featured drains made of both rectangular and wedge-shaped bricks, and terracotta ring wells, approximately 75 cm in diameter, possibly used as soak-pits for wastewater, were also discovered. Other artefacts from the NBPW levels included terracotta figurines of humans and animals, a sculpted ring stone fragment, a depiction of a horse and armoured rider, a clay sealing, small rings, and an agate disc. Notably, one NBPW dish had an elephant figure stamped on its base. Two terracotta seals with the names Svatirakhita and Seyankara were also found.

- In the upper Ganga valley, Hastinapura in Meerut district is a significant site with a published report (Lal, 1954–55). According to epic–Puranic tradition, Hastinapura was the Kuru capital until a flood prompted its relocation to Kaushambi. Jaina tradition holds that Rishabha, the first tirthankara, lived in Hastinapura, which Mahavira frequently visited. Period III at Hastinapura corresponds to the NBPW phase, dating around 600–200 BCE, characterized by planning, burnt-brick structures, and terracotta ring wells.

- Mathura emerged as a crucial city in early historical India. The Mahabharata and Puranas link it to the Yadava clan, including the Vrishnis, among whom Krishna was born. Strategically located at the entrance of the fertile Ganga plains, Mathura stood at the crossroads of northern trade routes and those leading south into Malwa and towards the western coast. Period I of the Mathura cultural sequence, identified at Ambarish Tila near the Yamuna north of Mathura city, is marked by PGW and reflects the gradual development of a village settlement. At Sonkh, 25 km southwest of Mathura, Period I, dating around 800–400 BCE, features PGW, BRW, and coarse grey ware, with no structural remains found, but indications of post-holes and a double ditch suggesting potential settlement enclosure (Hartel, 1993).

- Kampilya: The site of Kampilya, known as the capital of south Panchala, has been identified with Kampil in the Farukhabad district of Uttar Pradesh. Small-scale excavations at this site have indicated occupation from the Painted Grey Ware (PGW) phase onwards.

- Ahichchhatra: Ahichchhatra, located in the Bareilly district of Uttar Pradesh, also has evidence of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) levels. However, most of the structural details from this site relate to the period after the 2nd century BCE.

- Ayodhya: The ruins at Ayodhya, described in the Ramayana as the capital of Kosala during the time of Rama, cover a circuit of 4–5 km. Earlier excavations at this site revealed an occupation beginning with the early NBPW phase. The findings included very fine NBPW in different shades, as well as a grey ware with linear designs painted in black. Remains of houses made of mud or wattle and daub were discovered, but no baked brick structures were found. Artefacts made of iron and copper were also found at the site. Recent excavations in 2002–03 revealed many artefacts belonging to the NBPW phase, including terracotta objects such as broken votive tanks, weights, ear studs, discs, hopscotches, a wheel made on a disc, and a broken animal figurine. Other artefacts included a broken iron knife, glass beads, and a bone point. One notable find was a button-shaped light-blue glass object, possibly originally set in a ring, with the legend "shidhe" inscribed on it in 3rd century BCE Brahmi letters. Calibrated radiocarbon dates suggest that the NBPW phase at Ayodhya may date back to as early as c. 1000 BCE.

- Kaushambi: Kaushambi was the capital of the kingdom of Vatsa and an important point on trade routes connecting the Deccan, the Ganga valley, and the north-west. The site has been identified with Kosam village. Excavations at Kaushambi associated Period I with PGW, Period II with Black Rice Ware (BRW), and Period III with NBPW. It has been suggested that the impressive defences at the site were built as early as 1025 BCE, but it is more likely that they belong to a later period, perhaps around 600 BCE. Pali texts locate the Ghoshitarama monastery at Kaushambi, and monastic seals bearing the name "Ghoshitarama" confirmed the identification of the city.

- Sringaverapura: Excavations at Sringaverapura in the Allahabad district have indicated that the NBPW phase at this site dates back to around 700 BCE. The excavations primarily focused on a tank complex belonging to the early centuries CE, and there is limited information about earlier occupational phases. The Ramayana mentions Sringaverapura as a place where the sage Rishyashringa had his hermitage and where Rama crossed the Ganga during his exile.

The Middle and Lower Ganga Valley

Rajghat: Ancient Varanasi

- Rajghat, located northeast of Benaras, is recognized as the site of ancient Varanasi, a city renowned for its exquisite textiles and strategic position on northern trade routes.

- The archaeological findings at Rajghat reveal a complex cultural sequence spanning five or six periods.

- Period I (c. 800–200 BCE) is further divided into three sub-periods:

- Period IA : Characterized by iron objects, Black Red Ware (BRW), and red-slipped and coarse gritty red wares.

- Period IB : Marked the introduction of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), with evidence of burnt clay floors and pits lined with terracotta rings.

- Rampart : The settlement was likely surrounded by a rampart during the middle or early NBPW phase.

Ancient Shravasti: Capital of Kosala

- The site of ancient Shravasti, the capital of Kosala, has been identified with the ruins at Saheth and Maheth, located on the border of Gonda and Bahraich districts in Uttar Pradesh.

- Maheth : Represents the city of Shravasti. Saheth : Corresponds to the site of the ancient monastery of Jetavana.

- According to Buddhist tradition, Jetavana was gifted to the monastic community by Anathapindika.

- The ramparts surrounding the site likely date back to the 3rd century BCE.

Discoveries at Ganwaria and Piprahwa

- The findings at Ganwaria and Piprahwa, excavated by the Archaeological Survey of India under K. M. Srivastava, have clarified the location of ancient Kapilavastu.

- Piprahwa : Excavations uncovered sealings and a pot lid inscribed with the name of the Kapilavastu monastery, along with remnants of monasteries and shrines.

- Original Stupa : Evidence of what may be the original stupa built by the Sakyas over the relics of the Buddha has been identified.

- Ganwaria : Represents the town of Kapilavastu, with a thick occupational deposit divided into four periods:

- Period I (c. 800–600 BCE) : Characterized by fine grey, black polished, and red wares.

- Period II (c. 600–200 BCE) : Marked by the presence of NBPW.

- Periods III and IV (c. 200 BCE to 200 CE) : Indicate further developments in the settlement.

- Period I : Inhabited by people living in mud houses with wooden roofs. Period II : Introduction of burnt-brick structures.

Shravasti: Excavated Monasteries and Mound

The remnants found in and around the village of Basarh, located in the Muzaffarpur district of Bihar, have been linked to the ancient city of Vaishali. Vaishali was the capital of the Lichchhavis and the Vajji confederacy. This city was situated on the route from Magadha to the Nepal terai.

- Buddhist texts mention Vaishali frequently, while Jaina tradition regards it as the birthplace of Mahavira. Additionally, Puranic tradition associates Vaishali with a legendary king named Visala. The mound known as Raja Visal ka Garh exhibits signs of old fortifications, and a tank called Khorana Pokhar is believed to be the coronation tank of the Lichchhavis. Numerous antiquities and structural remains have been discovered here, some possibly dating back to the 5th or 4th century BCE.

- Rajgir, located about 40 miles southeast of Patna, is recognized as the site of ancient Rajagriha, which was the first capital of Magadha. An important trade route from Paithan to the middle Ganga valley ended here. This city had strong connections with the lives of both the Buddha and Mahavira. Archaeological explorations in Rajgir have primarily focused on identifying locations mentioned in Buddhist texts and the accounts of Xuanzang. Rajgir consists of two parts: Old Rajagriha and New Rajagriha. Old Rajagriha, situated among five hills, was enclosed by two stone fortification walls. New Rajagriha, also surrounded by stone fortifications, is located in the plain to the north. The extensive outer fortifications of Old Rajagriha extended through the hills, possibly covering 25 to 30 miles. Although these fortifications have not been dated, literary sources suggest they may date back to the time of Bimbisara, around the 6th century BCE. The fortifications around New Rajagriha likely belong to the time of Ajatashatru, around the 5th century BCE.

- In the Vinaya Pitaka, the Buddha predicts the future prominence of Pataliputra and the threats it would face from fire, water, and internal strife. The discovery of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) at Kumrahar and Bulandibagh in Patna indicates the presence of an early historical settlement in the area, which can be associated with ancient Pataliputra. However, little is known about the earliest occupation of this site. Ancient Champa, the capital of Anga, has been identified with the villages of Champanagar and Champapur, located 5 kilometers west of Bhagalpur in south Bihar. During the NBPW phase, the site was surrounded by defensive fortifications and a moat.

Excavations in Piprahwa

The archaeological site of Piprahwa, located in the lower Ganga valley, is currently undergoing excavations. This site is considered one of the most important in the region, and recent findings suggest that it may have been occupied much earlier than previously thought.

NBPW and Early Settlements

- NBPW levels at Wari Bateshwar have been dated to around 500 BCE, indicating early settlement in Bengal during the period of the mahajanapadas.

- Settlement studies, such as Erdosy’s research in the Allahabad district, reveal a four-level hierarchy of settlements in the Vatsa kingdom, with Kaushambi emerging as a significant centre.

- The early NBPW phase saw a population increase and the growth of settlements, with Kaushambi expanding and surrounded by defensive walls.

Hierarchy of Settlements

- The second tier included towns like Kara and Sringaverapura, known for manufacturing activities.

- The third tier consisted of smaller settlements with craft activities and iron smelting, while the fourth tier included villages of farmers and herders.

Long-term Trends

- Over the centuries, a fifth tier of settlements emerged, with increasing numbers of large secondary centres such as Bhita and Jhusi.

- There was also a rise in village settlements, which were no longer limited to areas near water resources.

S. B. Singh’s Study of Panchala (c. 1979)

- S. B. Singh’s research in the Panchala area of the upper Ganga valley identified a four-tier settlement structure during the NBPW period.

- Ahichchhatra, the capital of Panchala, was the largest site, growing into a massive fortified city by the 3rd century BCE.

- Atranjikhera emerged as a secondary fortified centre with diverse agriculture, craft activities, and trade.

- Other sites like Jakhera and various smaller villages contributed to the settlement landscape, although they were smaller in size.

Early Urban Development in Central India and the Deccan

While the primary focus is on north India, it is important to acknowledge the evidence of urban development in other regions during the period of approximately 600 to 300 BCE.

Central India

- In central India, cities like Tripuri in the Narmada valley near Jabalpur and Airakina (Eran) near Sagar were likely part of the Chedi kingdom during this time.

- The history of Tripuri dates back to the 2nd millennium BCE, but the exact timing of its transition to urban status remains unclear. Similarly, the settlement at Eran also has roots in the 2nd millennium BCE, with indications that it became a city during the Maurya period.

Ujjain and Avanti

- Ujjayini (modern Ujjain), situated along the Sipra river, a tributary of the Chambal, served as the capital of the Avanti kingdom. Ujjain emerged as a significant commercial hub, strategically located at the crossroads of northern Indian trade routes leading southwards and westwards.

The site of Ujjayini has been divided into four occupational phases:

Period I

- The earliest phase, known as Period I, is dated around 750 to 500 BCE. It is characterized by the presence of Black Red Ware (BRW) and some Painted Grey Ware (PGW) pottery.

- Artefacts from this period include terracotta spindle whorls, bone tools, iron arrowheads, spearheads, crowbars, spades, choppers, and knives.

- The settlement was fortified with a substantial mud wall, accompanied by a moat for added defense.

Period II

- Period II saw the introduction of pottery types such as black-slipped ware, BRW, and Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW).

- The architectural remains from this phase include structures made of mud, mud-brick, stone rubble set in clay, and burnt brick.

- A notable feature of Period II is the discovery of a large burnt-brick water tank and several terracotta ring wells.

- Evidence of industrial activity includes an iron-smelting furnace and workshops for crafting stone beads and bone arrowheads.

- Artefacts from this period include punch-marked coins, a variety of iron objects, and items made of terracotta, copper, and ivory.

Vidisha

- The ancient city of Vidisha is now found at Besnagar in the Raisen district of Madhya Pradesh. This location was significant along trade routes passing through the Malwa region.

- The rampart at Besnagar appears to have been constructed in the 2nd century BCE. During the early phase of the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), the site revealed evidence of Black and Red Ware (BRW) pottery, iron objects, punch-marked coins, and ring wells.

Ashmaka and Early Historical Sites in the Deccan

- In the Deccan region, the kingdom of Ashmaka, located along the Godavari River, was one of the 16 mahajanapadas. Paithan, known in ancient times as Pratishthana, is a crucial early historical site in this region, although it has not been thoroughly explored yet.

- The early historical occupation of Nasik dates back to around 400 BCE. Additionally, a mud core of a stupa discovered at Pauni in the Wainganga valley also seems to belong to this early period.

- Tagara, an important market town, is identified with Ter on the Terna River, and evidence from Period I at this site includes NBPW pottery.

- Adam, located in the Nagpur district, has revealed a 10-hectare site featuring an earthen rampart with gateways facing east. This rampart and the associated moat date to Period III, around 1000–500 BCE, and the rampart was later reinforced with a stone battlement.

- The site of Nagal, situated on the south bank of the Narmada River opposite the more well-known site of Broach (ancient Bharukachchha), has yielded evidence of a settlement possibly dating back to at least the 6th century BCE. Findings from Nagal include pottery, bone, and iron artifacts.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on Cities, Kings, and Renunciants - 2 - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What were the main impacts of the Persian and Macedonian invasions on Indian society and culture? |  |

| 2. How did Atranjikhera transition from a village to a town during early urban development? |  |

| 3. What archaeological findings have been discovered in Shravasti that indicate its significance during early historical India? |  |

| 4. What were the primary urban occupations and crafts in early historical India, and how did they contribute to economic development? |  |

| 5. How did the dynamics of trade and traders evolve during the early historical period in India? |  |