Cities, Kings, and Renunciants - 3 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Urban Occupations, Crafts, Guilds, and Money |

|

| Trade and Traders |

|

| Trade In Early Historical India |

|

| The Renunciatory Tradition |

|

| The Ajivikas |

|

Urban Occupations, Crafts, Guilds, and Money

Overview of Occupations in Early Buddhist Society

- Early Buddhist texts highlight a variety of occupations present in both rural and urban settings during that time.

- Occupations mentioned include farmers, cattle rearers, traders, and various service industry roles.

Service Industry Occupations

- Service industry roles included:

- Washermen

- Barbers

- Tailors

- Painters

- Cooks

Specialists in the King’s Service

- The king employed various specialists, including:

- Soldiers: Foot soldiers, archers, cavalry, elephant corps, and chariot units.

- Ministers (mahamachchas)

- Governors (ratthikas)

- Estate managers (pettanikas)

- Royal chamberlain (thapati)

- Elephant trainers (hattirohas)

- Policemen (rajabhatas)

- Jailors (bandhanagarikas)

- Slaves (dasas and dasis)

- Wage-workers (kammakaras)

Urban Occupations

- Urban occupations included:

- Physicians (vejja, bhisakka)

- Surgeons (sallakata)

- Scribes (lekha)

- Accountants (ganana)

- Money changers

Entertainers

- Types of entertainers included:

- Actors (nata)

- Dancers (nataka)

- Magicians (sokajjayika)

- Acrobats (langhika)

- Drummers (kumbhathunika)

- Fortune-tellers (ikkhanika)

- Courtesans (ganika)

- Prostitutes (vesi)

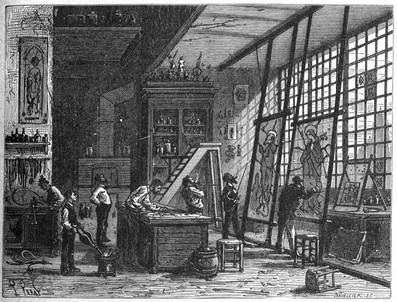

Artisans and Craftsmen

- The Pali canon refers to various artisans, some of whom likely lived and worked in or near cities, supplying goods for urban customers.

- Artisans included:

- Vehicle makers (yanakara)

- Ivory workers (dantakara)

- Metal smiths (kammara)

- Goldsmiths (suvannakara)

- Silk weavers (kosiyakara)

- Carpenters (palaganda)

- Needle makers (suchikara)

- Reed workers (nalakara)

- Garland makers (malakara)

- Potters (kumbhakara)

Localization of Industries and Hereditary Crafts

- Over time, certain industries became localized, with specific villages associated with particular artisan groups.

- Crafts also became hereditary, passed down through generations.

- This process was likely already in progress around 600–300 BCE.

Guilds and Corporate Organization

- The emergence of guilds is more directly evidenced in Buddhist texts.

- Various terms like shreni, nigama, puga, vrata, and sangha refer to different types of corporate organizations, including guilds.

- For instance, the guilds of Shravasti were known to provide regular food supplies for monks and nuns.

- The Vinaya Pitaka mentions these guilds, highlighting their role in supporting the monastic community.

- Further details about guild organization and activities are found in the Jatakas, which list 18 guilds and suggest a close relationship between guild heads and kings.

Coinage and Economic Changes

- Coinage marked a significant aspect of urbanism, with Pali texts providing the earliest references to coins such as kahapana, nikkha, kamsa, pada, masaka, and kakanika.

- Archaeological evidence of punch-marked coins, primarily made of silver, supports these literary references.

- The introduction of money did not eliminate barter but represented a qualitative shift in economic transactions, profoundly impacting trade and giving rise to usury (money-lending).

- Pali texts reflect the prevalence of usury, credit instruments, and practices such as pawning possessions, with debtors facing severe consequences, including exclusion from the Buddhist sangha until debts were settled.

- The growing availability of material goods was accompanied by the emergence of doctrines advocating the renunciation of material possessions, highlighting a societal shift in values.

The Gahapati and Setthi

- The early Pali texts from around 600–300 BCE reveal the emergence of new socioeconomic classes in north India, characterized by significant disparities in wealth, status, and control over productive resources.

- Gahapati, a term used in Pali texts, denotes a wealthy property-owner and producer of wealth, particularly associated with land and agriculture. This term reflects the changing social vocabulary and the broader meaning of household heads in the context of economic changes.

- Society during this period is often described as comprising three strata: Khattiya (warrior class), Brahmana (priestly class), and gahapati (wealthy landowners). Each stratum is linked to different ideals and domains, such as power and territory for the Khattiya, spiritual pursuits for the Brahmana, and work and craft for the gahapati.

- The political significance of the gahapati is underscored by his inclusion among the seven treasures of the chakkavatti or ideal ruler, indicating his important role in society.

Setthi in the Pali Canon

- The term setthi in the Pali canon refers to a high-level businessman involved in trade and money-lending.

- There are numerous references to extremely wealthy setthis living lavishly in cities like Rajagriha and Varanasi.

- The Mahavagga narrates the story of Sona Kolivisa, the son of a setthi, who was raised in such luxury that his delicate feet bled when he tried to live as a barefoot monk.

- This experience made him reconsider the monastic lifestyle, and the Buddha addressed this issue by permitting monks to wear shoes.

- The setthi depicted in Buddhist texts was a prominent and influential member of the urban community, with connections to kings.

Distinction between Gahapati and Setthi

- In early Pali texts, gahapati and setthi have distinct meanings and are never used interchangeably.

- For example, Anathapindika is consistently referred to as a gahapati, and only in the Jatakas is he described as a setthi.

- The compound word setthi-gahapati refers to a person with both rural and urban bases, possessing control over land and business enterprises.

- The wealth and affluence of setthis and setthi-gahapatis are evident from their presence among the clientele of the famous physician Jivaka, paying thousands of kahapanas in medical bills.

Trade and Traders

In Buddhist writings, various groups of people are depicted as traveling, including the Buddha and his followers, ascetics from different traditions, educators, learners, professionals, rulers, soldiers, and merchants. These diverse groups likely traveled along similar routes, and their journey accounts provide insights into the pathways used for travel, communication, and trade during that time. Archaeological findings further contribute to identifying these trade routes and interactions.

Uttarapatha

- The Uttarapatha was the primary trans-regional trade route in northern India.

- It began in the north-west, traversed the Indo-Gangetic plains, and culminated at the port of Tamralipti on the Bay of Bengal.

- The route included a northern and a southern sector, with various kingdoms located along it.

- The northern sector passed through Lahore, Jalandhar, Saharanpur, and continued through the Gangetic plains to Bijnor, Gorakhpur, and into Bihar and Bengal.

- The southern sector connected Lahore to Delhi, Kanpur, Varanasi, Allahabad, and then to Pataliputra and Rajagriha.

- Numerous feeder routes linked to the Uttarapatha, connecting it with regions like Rajasthan, Sindh, and the Orissa coast.

Archaeological Evidence

- Archaeological findings support the existence and usage of the Uttarapatha as indicated in literary sources.

- The distribution of Painted Grey Ware (PGW) settlements reflects a similarity in material culture and cultural interactions across northern India, from Cholistan to the upper Ganga plains.

- By the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) phase, there is archaeological evidence for the entire stretch of the Uttarapatha.

- The wide distribution of NBPW suggests extensive inter-regional contacts.

Trade Goods

- Various raw materials and finished products were exchanged along the Uttarapatha.

- Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and central Asia has been found at sites from the Swat valley to Bengal.

- Silver, possibly imported from Afghanistan or central Asia and used for coinage, has been discovered along the route.

- Semi-precious stones like amethyst and topaz were traded from eastern India to the middle and upper Ganga valley.

- Shell was imported from the eastern coast to sites in the lower and middle Ganga valley.

Trade and Commerce

- Routes: The Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha were important trade routes, with the Uttarapatha being a land-and-river route along the Ganga and its tributaries, and the Dakshinapatha connecting Pataliputra to Pratishthana and ports on the western coast.

- Riverine and Land Movement: Traders and goods moved along rivers like the Ganga, Yamuna, Ghaghara, and Sarayu, as indicated by the distribution of PGW and NBPW sites. Buddhist texts mention ferries for river crossings, but land movement was also crucial, with caravans of traders and Buddhist monks traveling on foot.

- Dakshinapatha: This route, operational from the early historical period, was vital for trade and interaction. The Vindhyas supplied raw materials like iron, copper, and stone to the Ganga valley along this route.

- Trade Practices: Buddhist texts describe large caravans, tolls, taxes, and customs officials monitoring merchandise. Royal officials, known as rajabhatas, were responsible for safeguarding travelers from robbers and ensuring their safety along the roads connecting major cities.

Trade In Early Historical India

Internal Trade Routes:

- These routes connected different parts of India and were crucial for the movement of goods within the subcontinent.

- They joined with external routes that linked India to other regions, facilitating a vibrant trade network.

Overland Trade with Central Asia:

- Routes from Taxila to north Afghanistan and Iran were vital for acquiring raw materials like silver, gold, lapis lazuli, and jade.

- There was likely a long-distance trade in fine wood between India and Mesopotamia.

Historical Significance of Central Asia Route:

- The trade route through Central Asia had been significant since Neolithic times, facilitating the exchange of goods.

- The route via the Bolan Pass and through north Afghanistan was also crucial for trade.

Commercial Centres:

- Cities like Taxila and Charsada emerged as major commercial hubs due to their strategic location along these trade routes.

Invasions and Trade Routes:

- The routes into India from the northwest were not only used by traders but also by invading Persian and Macedonian armies.

- The route from Bengal to Myanmar was likely important, with jade possibly being an import from Myanmar.

Sea Trade in Early Historical India:

- References in the Pali canon, such as the Anguttara Nikaya, indicate the practice of sea trade, where merchants would use birds to sight land.

- The Jatakas contain numerous accounts of sea voyages, highlighting the significance of maritime trade during this period.

Exported Commodities:

- Sites along the eastern and western coasts of India likely exported commodities such as sandalwood and pearls to West Asia and the Mediterranean.

- Maritime trade with Southeast Asia also began during the early historical period, expanding India’s trade networks.

Emergence of Traders:

- The expansion of trade led to the emergence of traders as a significant urban group.

- Buddhist texts regarded trade (vanijja) as one of the high occupations, reflecting the economic affluence of traders.

Socio-Economic Classes in North India:

- From the 6th century BCE, there is evidence of the emergence of distinct socio-economic classes in north India.

- Buddhist texts highlight disparities in wealth and status, with references to very poor (dalidda) people and contrasts between fortunate wealthy individuals and unfortunate poor people.

Kinship Ties and Caste:

- Despite the emergence of socio-economic classes, kinship ties remained crucial and were eventually integrated into the caste system.

- Terms like nati and nati-kulani refer to the extended kin group, beyond the immediate family, indicating the importance of kinship in social structure.

- Kula denotes an extended patrilineal family, further emphasizing the significance of kinship ties.

Buddhist Monastic Rules:

- Although Buddhist monks were expected to renounce family ties, monastic rules allowed for some contact with family members, reflecting the strength of kinship bonds.

- Monks were permitted to visit sick or dying relatives, and exceptions were made for maintaining family contacts during the monsoon retreat (vassavasa).

Influence of Kinship on Buddhism:

- Kinfolk, such as Mahapajapati Gotami and Ananda, had a significant influence on the Buddha and the monastic order, highlighting the importance of kinship ties.

- The Buddhist monastic order provided an alternative form of brotherhood (or sisterhood in the case of nuns), but it did not completely replace conventional kinship bonds, showcasing the enduring strength of these relationships.

Varnas and inter-varna marriages

- Varnas are hereditary classes central to the social structure of the Brahmanical tradition. Ideally, marriages were to occur within the same varna, making them endogamous. However, the Dharmashastra recognized certain inter-varna marriages, specifically those between a man of a higher varna and a woman of a lower varna. These hypergamous unions were called anuloma marriages.

- In contrast, marriages where a woman of a higher varna married a man of a lower varna, known as hypogamy, were termed pratiloma unions and were not approved. The most disapproved pratiloma union was between a Brahmana woman and a Shudra man. The discussion and grading of inter-varna marriages in these texts indicate that such unions occurred and that varnas were not strictly endogamous.

Varnas and Occupations

Varnas and their ideal occupations were as follows:

- Brahmana: Studying and teaching the Veda, performing sacrifices for himself and others, and giving and receiving gifts.

- Kshatriya: Studying, performing sacrifices for himself, bestowing gifts, and especially protecting people.

- Vaishya: Similar to the Brahmana and Kshatriya, but with a focus on agriculture, cattle rearing, trade, and money-lending.

- Shudra: Serving the higher varnas.

- Apad-dharma (dharma in times of distress or emergency) allowed individuals to pursue vocations considered inappropriate for their varna during times of emergency, adversity, or distress. This flexibility indicates that people were not strictly adhering to the norms of varna-dharma.

Activities in Times of Adversity

The Gautama Dharmasutra (7) outlines how varna duties can be relaxed during difficult times, with a focus on the Brahmana.

- Teaching and Learning: In times of adversity, a Brahmana can receive Vedic instruction from a non-Brahmana, follow him, and obey him. However, once the study is completed, the Brahmana regains his higher status.

- Teaching and Officiating: A Brahmana can teach, officiate sacrifices for, and receive gifts from people of all classes, in a hierarchy of honor. If these roles are not available, he can resort to the occupations of a Kshatriya, and if those are unavailable, to the occupations of a Vaishya.

- Trading Restrictions: There are strict prohibitions on trading certain goods, including perfumes, seasonings, prepared foods, various cloths and skins, milk and milk products, fruits, flowers, medicines, honey, meat, water, and animals for slaughter. Human beings, barren cows, heifers, and pregnant cows are also off-limits for trade. Some sources suggest avoiding trade in land, rice, barley, livestock, and horses. Bartering is restricted to seasonings and animals, but uncooked food can be exchanged for cooked food for immediate use.

- Occupation Flexibility: If traditional occupations are not viable, one may engage in any occupation except that of a Shudra. In extreme situations, even a Brahmana can resort to the use of arms, and a Kshatriya can adopt the occupations of a Vaishya.

- Buddhist and Jaina Perspectives: Buddhist and Jaina texts also reference the varna order, but without the strong religious sanction found in Brahmanical tradition. They viewed it as a social construct based on natural inclinations and aptitudes, placing the Kshatriya above the Brahmana in the varna hierarchy.

- Gotra and Brahmana Identity: Gotra, or clan affiliation, was crucial to Brahmana identity. Buddhist texts often mention Brahmanas by their gotra, and non-Brahmanas also used gotra names. The Buddha and Mahavira are examples of this practice, with the Buddha being referred to as "Gotama," a gotra name. This usage may reflect the effort of Buddhist and Jaina traditions to establish parity between Brahmanas and their own preceptors.

- During this period, social identity was increasingly associated with jati(caste), which was based on factors such as lineage and occupation. The Dharmasutras(ancient texts on social and legal norms) attempted to explain the origin of jatis by proposing the idea of varna-samkara, suggesting that jatis emerged from inter-varna marriages. This explanation allowed the Dharmashastra tradition to uphold the varna theory while acknowledging the reality of jatis.

- Although the concepts of endogamy (marrying within a specific group) and commensality (rules about sharing food and water) were not fully established at this time, the foundations of the caste system can be traced back to the 6th century BCE.

- In ancient texts, the terms varna, jati, and kula(lineage) are sometimes used interchangeably, while at other times they have specific meanings. The varna order remained an important reference, and the categories of Brahmana (priests) and Kshatriya (warriors) held significance. However, individuals who would have theoretically belonged to the Vaishya (merchants) and Shudra (laborers) categories are often identified by their specific occupations, which were closely tied to their kulaand jati. This indicates that varna was more of a theoretical concept associated with the upper categories, while a person's identity was primarily based on occupation, lineage, and caste.

- Some scholars argue that the varna system was the precursor to the jati system and that the two were never sharply distinguished in ancient literature. Instead, their relationship was characterized by overlap, interaction, and gradual integration.

- The term "caste" in English derives from the Portuguese word castas, which referred to species or breeds in animals and plants, as well as to tribes, clans, races, or lineages within human societies.

Portuguese traders in the 16th and 17th centuriesfirst used this term in the context of Indian society. Interpretations of caste vary widely and can be broadly classified into two types:

- Materialist Interpretation:This view sees caste as a means to rationalize and conceal material inequalities through the lens of purity and pollution.

- Idealist Interpretation:This perspective views caste as primarily a product of religious and cultural ideas related to purity and pollution.

- Another interpretation highlights the connection between caste and the political domain, emphasizing the role of caste in political structures and power dynamics.

Varna and Jati

- Varna and jati are both hereditary social classifications in India, but they are not the same thing. Varna refers to the four (or five) broad categories of society, while jati includes the numerous castes and sub-castes, which are constantly evolving.

Key Differences:

- Number: There are fixed four varnas, but the number of jatis is vast and continually increasing.

- Hierarchy: The ranking among varnas is fixed, with Brahmanas at the top and Shudras at the bottom. In contrast, the ranking of jatis is fluid and can vary based on factors like land control, wealth, and political power.

- Interactions: The rules governing social interactions and food acceptance among varnas were less strict than those among jatis, which were based on ideas of purity and pollution.

- Endogamy: Varnas were not strict endogamous units, as inter-varna marriages (anuloma) were allowed.

Historical Context:

Brahmanical Tradition:

- The Brahmanical tradition played a significant role in shaping the perception of ancient Indian society as being divided into four varnas for a long time.

- This perception led many to believe that varna was the basis of jati, which is not accurate.

Buddhist Tradition:

- In the Buddhist tradition, the hierarchy among varnas is different, with the Kshatriya coming first and the Brahmana second. However, like in the Brahmanical tradition, the order is still fixed.

Caste Fluidity and Disputes:

- The ranking of jatis is not fixed and can vary between regions and localities. Factors such as land control, wealth, and political power influence caste ranking.

- Disputes over caste ranking can occur, even among Brahmanas and outcastes.

Sanskritization:

- Sanskritization is the process by which castes try to upgrade their status by adopting practices associated with higher castes.

- This may include changes in diet, family structure, and occupation.

Rules of Commensality:

- The rules of commensality, which govern social interactions and food sharing, were more clearly defined with reference to jatis.

- These rules were based on ideas of purity and pollution, and varied among different jatis.

1. Introduction

- The varna system, found in ancient texts, classifies society into four groups: Brahmanas (priests and teachers), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and landowners), and Shudras (laborers and service providers).

- This system was not just about social standing but was linked to specific roles and duties. Over time, the varna system became intertwined with the concept of jati, or sub-caste, which defined more specific social groups within the broader varna categories.

2. Differences between Varna and Jati

- Varna refers to a broader classification based on occupation and social function, while jati denotes specific sub-groups within this classification, often determined by birth.

- Initially, jatis were linked to particular occupations, but over time, the distinction between varna and jati became less clear, with many claiming higher varna status to gain legitimacy.

- The varna system was more about social identity and theoretical categorization, whereas jati was the practical basis for social interactions, marriages, and occupations.

3. Emergence and Evolution of Jatis

- Jatis likely emerged from a mix of factors, including the hereditary nature of certain crafts, the integration of tribal groups into the Brahmanical framework, and a social structure that prioritized birth and regulated hierarchy through marriage rules and endogamy.

- Territorial and occupational distinctions also contributed to the formation of segmented identities within the jati system.

- Over time, the functions and significance of varna and jati have evolved, and their precise nature in ancient times cannot be directly equated with contemporary understandings.

4. Varna-Samkara in Dharmasutras

- The Dharmasutra concept of varna-samkara was crucial for integrating diverse groups into the social hierarchy, illustrating the fluidity and adaptability of social classifications.

- Pali texts highlight the variability in social status among different jatis, linking them to specific occupations and underscoring the diverse social landscape of ancient India.

Untouchability in Ancient Texts Early References

- The term asprishya, referring to a social group deemed permanently 'untouchable' by birth, first appears in the Vishnu Dharmasutra, written between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE. However, the practice of untouchability, a severe form of social subordination and oppression, clearly existed earlier and intensified over time.

- Chandalas in Early Texts: In early Dharmashastra texts, Chandalas were sometimes classified as Shudras. However, a distinction between the two was established relatively quickly. The Apastamba Dharmasutra describes a Chandala's birth as a consequence of evil deeds in a previous life, while other texts like the Gautama, Baudhayana, and Vasishtha Dharmasutras depict the Chandala as the child of a Shudra man and a Brahmana woman, highlighting their lowly origin.

- Prejudice Against Chandalas: The Dharmasutras exhibit extreme prejudice against Chandalas, likening them to dogs and crows. Contact, even accidental, with a Chandala was considered polluting. For instance, the Apastamba Dharmasutra prescribes severe purification rituals for touching, speaking to, or seeing a Chandala.

- Antyajas and Purification: Contact with other lowly groups, known as antyajas, required less severe purification methods, such as washing the affected body part or sipping water.

- Restrictions and Penalties: The Dharmasutras impose strict penalties for men engaging in sexual relations with Chandala women. They also reflect the existence of male and female slaves, with various categories of slaves described in texts like the Digha Nikaya and Vinaya Pitaka. Digha Nikaya mentions different types of slaves, including those born into slavery, bought slaves, and those enslaved from other countries. It also notes the possibility of slave manumission, with rules in the Buddhist sangha regarding the admission of freed slaves.

Reconstructing Resistance and Subordination in Ancient India

1. Historical Bias and Resistance

- The literary sources from ancient India have an elitist bias, making it challenging to understand how groups like the Chandalas and slaves reacted to their subordination and oppression.

- Despite this bias, instances of resistance have been identified, such as in the Buddhist canon.

2. Instances of Resistance

- One instance of resistance noted by Chakravarti is from the Vinaya Pitaka, where the dasa-kammakaras (laborers) of the Sakyas attacked the womenfolk of their masters in the woods as an act of vengeance.

- Another instance is the story of Kali, a dasi (female servant), and her mistress Vaidehi in the Majjhima Nikaya. Kali, believing that Vaidehi's gentle nature was due to her own good conduct, decided to test her by waking up late and ignoring her calls. This test proved that Vaidehi's temper was not as calm as it seemed.

3. Challenge of Unearthing Marginalized Voices

- While social tensions and conflicts can be identified in ancient texts, uncovering the lives and ideas of subordinated and marginalized groups is more difficult.

- Subordination often meant exclusion from literary culture, making it hard for historians to retrieve the histories of those who lived outside elite society.

- Historians need to carefully read between the lines of available texts to uncover the histories of these marginalized groups.

Gender, Family, and Household

- The political, economic, and social changes of the time were linked to developments within the family and household.

- New ethical standards were required, emphasizing strict control over women's sexuality and reproductive capacity for patrilineal property transmission and maintaining the endogamous caste structure.

- Strengthening patriarchal authority and emphasizing norms related to marriage and women's chastity were means to exercise such control.

Role of Texts in Defining Social Values

- Buddhist and Jaina texts outline ideal conduct for monastic and household community members.

- However, Brahmanical Dharmasutras and Grihyasutras make the most systematic attempts to define and regulate social values and practices, reflecting the centrality of the householder stage (grihastha) in this tradition.

- It is crucial to distinguish between the ideal situations projected in these texts and the actual conditions of their time, requiring a critical reading of the texts.

Household Structure in Ancient India

- The household could include:

- Unmarried children

- Married sons and their families

- Husband’s parents

- Slaves and servants

- The terms used for the household unit are kutumba (rare), ghara, and kula.

- kulapati was the head of the family, and kulaputa referred to junior males.

- Household labor was supplemented by wage laborers and, to a lesser extent, by slaves.

Marriage in Ancient India

- Central to Householder Life: Marriage was a fundamental aspect of a householder's life.

- Approved Type of Marriage: Buddhist texts favored marriages arranged by parents, especially when the bride and groom were young and chaste.

- Types of Unions: The Vinaya Pitaka describes 10 types of unions between a man and a woman. Most involve economic exchange or the woman's subordinate position.

- Dharmasutras Classification: Marriages were classified into eight types, including Brahma, Daiva, Arsha, Prajapatya, Gandharva, Asura, Rakshasa, and Paishacha.

- Brahma Marriage: The father gifts his daughter to a learned man.

- Daiva Marriage: The daughter is given to a priest during a sacrifice.

- Arsha Marriage: Involves the gift of cattle, not the sale of the daughter.

- Prajapatya Marriage: The father gifts the daughter with a blessing for the couple.

- Asura Marriage: The bridegroom offers wealth to the bride and her family.

- Gandharva Marriage: A union based on mutual love and consent.

- Rakshasa Marriage: Forcible abduction of a woman.

- Paishacha Marriage: Involves non-consensual sexual relations.

Marriage Types and Practices in Ancient India

- Brahma Marriage: This was considered the most honorable type of marriage. It involved giving the bride away with respect and without expecting anything in return.

- Paishacha Marriage: This was viewed as the least acceptable form of marriage. It involved taking a woman when she was in a vulnerable state, such as being asleep or intoxicated.

Early Dharmasutras on Marriage Timing

- Gautama Dharmasutra: This text emphasized that a girl should be married soon after she starts menstruating. If her father fails to do so, he incurs sin. If a father does not find a husband for his daughter within three months of her first menstruation, the girl should find her own husband.

- Baudhayana Dharmasutra: This text advised that a father should marry off his daughter to any man, even one lacking good qualities, rather than keeping her at home after she reaches puberty.

Rites and Rituals in Grihyasutras

- Central Role of Priest: The priest played a dominant role in marriage ceremonies, which were typically held in the bride’s parental home.

- Relationship Aspects: The marriage ceremony emphasized various aspects of the husband-wife relationship, including mutual support, friendship, sexual and procreative duties, and the wife’s subordination to the husband.

- Flexibility in Rituals: The Grihyasutras allowed for the adoption of practices devised by women during marriage ceremonies, recognizing their importance.

Other Domestic Rites in Grihyasutras

- The Grihyasutras also detailed various other domestic rites of passage, emphasizing their significance and the role of Brahmana priests in these rituals.

- They highlighted the close relationship between the grihapati (head of the household) and the domestic fire, further solidifying the Brahmanical foundation of these practices.

Widow Remarriage and Niyoga

- Widow Remarriage: The early Dharmasutras did not support widow remarriage but specified a waiting period for abandoned women before they could remarry.

- Niyoga: The early smritikaras had mixed feelings about niyoga, the practice of a widow having children with her brother-in-law or another man. Gautama recognized sons born of niyoga as legal heirs, while Baudhayana considered such unions sinful and emphasized that the male partner was the father.

Marriage, as per the Grihyasutras

The Grihyasutras present various details and sequences for the events and ceremonies leading up to marriage. While there are variations, a basic framework can be outlined:

- Timing of Marriage : Marriage should be fixed during the northern movement of the sun, in the period of the waxing moon, and on an auspicious day.

- Proposal and Acceptance : The groom-to-be sends learned Brahmanas as messengers to the girl’s house to convey his acceptance of the marriage. Relatives from both sides accept the alliance.

- Preparation of the Bride : The bride-to-be is specially bathed, and her hair is washed in preparation for the ceremony.

- Kindling of Fire : The prospective groom kindles the fire and makes a number of offerings, signifying the sacredness of the union.

- Kanyadana (Giving Away the Daughter) : Participants sit around the fire, and the father gives his final, oral acceptance of the union. Gifts are exchanged to formalize the agreement.

- Madhuparka : The bridegroom is honored with a seat, his feet are washed, and he is offered a honey mixture. This is followed by a meal of meat (cow, goat, fish) or vegetarian fare.

- Hastagrabha/Panigrahana : After the fire is established and offerings made, the husband grasps the bride’s hand, symbolizing his commitment to her. Different ways of grasping the hand are believed to influence the sex of future children.

- Lajahoma : The bride makes three offerings of roasted grain mixed with shami leaves while the bridegroom recites specific formulae. This ritual signifies prosperity and nourishment.

- Attaining Stability : The bride or couple steps on a stone, symbolizing stability in their union.

- Agniparinayana : The groom takes the bride around the fire, reciting vows of unity, harmony, and the desire for offspring, emphasizing the sacred nature of their union.

- Saptapadi (Seven Steps) : The couple walks seven steps together, each step symbolizing a specific blessing, such as sap, juice, wealth, comfort, offspring, seasons, and friendship. Water is sprinkled on their heads as a sign of purification.

- Conclusion of Ceremony : Spectators depart, and the groom gives gifts to the Brahmanas and the bride’s father. The couple leaves for the groom’s house, carrying their household fire, symbolizing the continuation of family traditions.

Marriage Rites and Rituals

The marriage rite is considered complete with the saptapadi, but there are several other important rituals that take place when the couple arrives at the groom's house. One of these is the dhruvarundhatidarshana, where the husband points to the pole star and encourages his wife to be as stable and firm as the star. Some believe that this ritual marks the true end of the marriage rite.

The pancha-mahayajnas are a set of five great sacrifices that became increasingly important in later Vedic texts and were deemed obligatory for Brahmanas. These rituals include:

- Brahmayajna: Involves the study and teaching of the Veda.

- Pitriyajna: Pertains to making offerings to ancestors.

- Daivayajna: Involves making offerings into the fire.

- Bhutayajna: Concerns making offerings to all beings.

- Manushyayajna: Involves honouring guests.

- Unlike the shrauta sacrifices that required priests, these mahayajnas were to be performed by householders themselves. Initially, they were seen as a way of fulfilling a man's duties to various beings in the universe.

- However, later Dharmashastra texts interpreted them as atonements for harm caused to various beings during daily household activities. It's worth noting that these mahayajnas were simple ceremonies performed by householders and were considered yajnas in a metaphorical sense.

Sapinda Relationships

Sapinda relationships were crucial in Dharmashastra discussions regarding marriage, inheritance, and rules of purity and impurity among relatives after a person's death. Brahmanical texts prohibited marriage among sapindas, and this prohibition was believed to apply to all varnas, including Shudras.

Different interpretations of sapinda relationships exist in later Dharmashastra texts:

- Body Part Transmission: Sapindas are those connected by sharing particles of the same body. For example, father, son, and grandson are sapindas because body particles are transmitted from father to son and then to grandson.

- Maternal Connections: The son also has sapinda relations with his mother, and this extends to his maternal grandfather, aunt, and uncle.

- Spousal Relations: Husband and wife are sapindas because they produce a son together. The wives of brothers are also considered sapindas because they produce sons from their husbands, who share the same body (their father).

Marriage and Kinship

Marriage and Kinship in Ancient India

The Yajnavalkya Smriti outlines the sapinda circuit, which defines the boundaries for permissible marriages. According to Yajnavalkya:

- On the mother’s side, five ascending and descending generations are considered.

- On the father’s side, seven ascending and descending relations are counted.

Varied Opinions Among Lawgivers

Different ancient lawgivers had varying opinions on:

- The number of degrees of relationship allowed for marriage.

- The exact point where the line between permissible and impermissible marriages is drawn.

Apastamba Dharmasutra's Stance

The Apastamba Dharmasutra (1.7.21.8) clearly states that:

- Sexual relations with uterine relatives of one’s parents, such as mothers, sisters, and their children, are sinful.

This ruling prohibits marriages between:

- A man and the daughter of his maternal uncle.

- A man and the daughter of his paternal aunt.

Regional Variations in Marriage Customs

Despite the Apastamba's strictures, the same text (1.19–26) acknowledges that:

- Marrying one’s maternal uncle’s daughter or paternal aunt’s daughter is a customary practice in southern India.

Baudhayana, another lawgiver, criticizes those in northern India who follow these practices, implying regional differences in marriage customs. Divisions Among Smritikaras

Different smritikaras (lawgivers) had varied stances on cross-cousin marriages:

- Some forbade these marriages regardless of regional customs.

- Others, like Apastamba, showed tacit approval of such practices in the south, indicating a lack of consensus.

Marital Practices and Household Dynamics

Marital Practices

- Monogamous and Polygynous Marriages: Texts from the period acknowledge both monogamous and polygynous marriages.

- Wives Permitted per Caste: The Vasishtha Dharmasutra (1.24) specifies the number of wives a man can have based on his caste:

- Brahmana: Allowed three wives.

- Kshatriya: Allowed two wives.

- Vaishya and Shudra: Permitted only one wife.

- Divorce and Remarriage: The possibility of divorce and remarriage in certain situations is hinted at in stories like that of Mahagovinda from the Digha Nikaya 2. In this story, Mahagovinda, upon deciding to renounce worldly life, offers to give his 40 wives to another man if they wish. However, the wives decline the offer and choose to follow him in his path of renunciation.

Adultery and Its Consequences:

- Severe Penalties for Women: The Vinaya Pitaka (4) recounts an instance involving a Lichchhavi man who seeks the approval of his clan members to kill his wife for committing adultery. This reflects the harsh consequences faced by women accused of adultery during that period.

Marital Residence:

- Patrilocal Marriages: Marriages during this time were patrilocal, meaning that after marriage, the wife would typically move to live with her husband’s family.

Role of the Householder in Early Grihyasutras

- Grihyasutras Overview: The early Grihyasutras provide detailed insights into the relationships and dynamics within a household. At the core of these texts is the figure of the grihapati, or householder, who is depicted as the central figure and authority within the household unit.

Importance of the Household: The household is portrayed as essential for several reasons:

- Progeny: The household is seen as the primary site for producing offspring, which is crucial for continuing the family line.

- Debt to Ancestors: The grihapati is believed to owe a debt to his ancestors, which can be fulfilled through the establishment and maintenance of a household, ensuring the continuation of the family lineage.

Role of the Wife: The study by Jaya S. Tyagi (2002) highlights the dual potential of the wife within the household:

- Destructive Potential: The wife is seen as having the potential to disrupt or harm the household by negatively impacting praja (progeny), pashu (animals), and pati (husband).

- Constructive Potential: Conversely, the wife also has the capacity to contribute positively to the household and its well-being.

Marriage in Ancient India

- The most common term for a wife was jaya, meaning "bearer of her husband’s children."

- There are different views in ancient texts about whether a wife could perform certain domestic rituals. Some Grihyasutras (ancient texts on domestic rituals) allow women to do morning and evening offerings in the domestic fire. However, they could not act independently as the yajamana (the person in charge) in larger sacrifices.

- When a wife died, the husband was expected to cremate her using flames from their domestic fire and to establish a new fire when he remarried.

- Some texts, like the Ashvalayana Grihyasutra, suggest that when a woman’s husband died, she was to lie on the funeral pyre but should be pulled away by designated males before it was lit. This act symbolized her willingness to accompany her husband to the afterlife, but her place was still among the living.

Impact of Private Property on Family Structure

- The rise of private land ownership significantly affected family structure and dynamics. Inheritance became a crucial issue, with property typically passing down through the male line.

- Buddhist texts indicate that both maternal and paternal property was usually divided among sons. If there were no sons, the property would go to the next of kin or be claimed by the state.

- For instance, in the Vinaya Pitaka, a mother pleads with her monk son to produce an heir to prevent the family property from going to the Lichchhavis. Similarly, the Samyutta Nikaya mentions king Prasenajit taking over the property of a setthi-gahapati who died without male heirs.

- Wives and daughters were generally excluded from inheriting a deceased man’s property. Some Buddhist texts also note instances where a father would transfer his property to his son or another close male relative during his lifetime.

Dharmashastra Views on Inheritance

- The Dharmashastra, an ancient legal text, prioritizes male heirs, especially sons, in inheritance matters. The Baudhayana Dharmasutra identifies a core group of heirs, including a man’s brothers, son, grandson, and great-grandson from a wife of the same varna (social class).

- The Apastamba Dharmasutra states that if a son cannot inherit, the property should go to the nearest sapinda (a relative connected by blood). While it mentions the daughter, it does not consider the wife as a potential heir.

- The Gautama Dharmashastra further emphasizes male preference in inheritance, reflecting the broader societal norms of the time.

Preference for Sons

- As the household became more patriarchal, the preference for sons over daughters persisted. Sons were seen as essential for performing funerary rites, propitiating ancestors, and continuing the family lineage.

- Texts like the Digha Nikaya and the Vinaya Pitaka reflect this preference, with parents desiring sons for their contributions to family possessions and lineage. The Samyutta Nikaya includes a story where the Buddha advises King Prasenajit of Kosala that a daughter could be just as valuable as a son, highlighting ideals of womanhood.

Varied Social Customs

- Social customs regarding inheritance and the value of sons versus daughters likely varied greatly depending on social group, region, and locality. The Dharmashastra recognized three sources of dharma: shruti (heard), smriti (remembered), and sadachara or shishtachara (good conduct).

- The Baudhayana Dharmasutra mentions different customs from the north and south of India. In the south, customs include eating with someone who hasn't undergone the sacred thread ceremony, eating with one's wife, consuming stale food, and marrying the daughter of a maternal uncle or paternal aunt.

- In the north, customs involve dealing in wool, drinking alcohol, selling animals with teeth in both the upper and lower jaws, engaging in the arms trade, and going to sea. The text suggests that these practices should be followed according to local customs, but not in places where they are not customary.

- However, the law-giver Gautama disagreed, viewing these northern and southern practices as contrary to the traditions of the shishtas, or learned Brahmanas, and therefore not acceptable anywhere. It's important to note that these texts primarily reflect the practices and norms of the upper classes in society and explicitly exclude the Shudras from their discussions on samskaras.

The Renunciatory Tradition

During the period of urban prosperity characterized by class and caste differences, there emerged a contrasting group of renunciants advocating for the abandonment of attachment to material possessions and social ties. These renunciants, known by various terms such as paribbajaka (Sanskrit: parivrajaka, meaning 'wanderer'), samana (Sanskrit: shramana, signifying 'one who strives to realize the truth'), and bhikkhu (Sanskrit: bhikshu, meaning 'one who lives by begging alms'), were individuals who had forsaken their homes to live as wanderers, relying on food and alms offered by compassionate or generous householders.

- Although the concepts of renunciation and asceticism were not entirely new, as the householder was central to the Vedic tradition, Vedic texts did contain terms like vanaprasthi, tapasi, yogi, yati, vairagi, muni, vaikhanasa, and sannyasi, all of which carried ascetic or renunciatory connotations. The married householder, while central to the ritualistic aspect of the Vedic tradition, was not relevant to the Upanishadic pursuit of knowledge.

- The early Dharmasutras provide the first comprehensive references to the four ashramas - brahmacharya (celibate studenthood), grihastha (householder stage), vanaprastha (partial renunciation), and sannyasa (total renunciation). According to Olivelle's study (1993), the four ashramas were initially viewed as four alternative ways of life for a snataka (a young man who had completed Vedic studies) and suggests that the authors of this scheme may have been influenced by early Upanishadic thought favoring celibacy and individual choice over ritualism.

- There were varying opinions among the early Dharmasutras regarding the legitimacy and relative merits of the ashramas. The Gautama and Baudhayana Dharmasutras criticized the ashrama scheme, with Gautama asserting that a young man must enter the grihastha stage based on Vedic authority and Baudhayana describing the ashramas as a devilish invention, emphasizing the necessity of marriage, procreation, and sacrifices. In contrast, the Apastamba Dharmasutra accepted the ashrama scheme, asserting the equal value of all ashramas and denying the superiority of the celibate stages over the householder stage. The appropriate timing for entering the third and fourth ashramas was also a subject of debate.

- The Smritis present the ashramas as an ideal sequence of four stages in the life of a dvija male. Although renunciation was eventually included in the ashrama framework during the sannyasa stage, it differed from the renunciation advocated by Buddhist and Jaina traditions. In these traditions, renunciation could span an entire adult lifetime and was considered the only path to knowledge and liberation, making it urgent and accessible to all, regardless of class, caste, or gender. By renouncing the world, individuals did not embark on a solitary journey but joined a community of renunciants.

Relationship Between the Householder and Renunciant

- The householder and renunciant represent opposite ends of the social spectrum in Buddhist and Jaina traditions.

- Their relationship is marked by both opposition and dependence.

- Renunciants rely on householders for food and material support, while householders seek guidance and wisdom from renunciants.

- Despite their differences, the worlds of the renunciant and householder are interconnected.

Renunciant Teachers in the 6th–5th Centuries BCE

- During this period, various renunciant teachers offered diverse perspectives on existential questions.

- While figures like the Buddha and Mahavira were prominent, other teachers and their schools did not survive, known only through critiques in Buddhist and Jaina texts.

Interaction and Competition Among Shramana Traditions

- There were likely interactions between different shramana traditions, as seen in similarities in doctrines and practices.

- However, competition for followers also led to tension and rivalry among these groups.

Purana Kassapa

- He was a teacher who rejected the idea of moral and immoral distinctions and denied that actions had consequences.

- He believed that good actions, like liberality, self-control, and honesty, did not lead to the accumulation of merit, and deeds like killing, stealing, and lying were not sinful.

Ajita Keshakambalin

- He taught a materialist doctrine, arguing that actions earned neither merit nor demerit, the body returned to the elements after death, and there was no rebirth.

- His materialist views link him to the later Charvaka school of thought.

Pakudha Kachchayana

- He taught that elements such as earth, water, fire, and air, as well as happiness, sorrow, and life, are fixed and unchanging, and do not affect each other.

- According to him, human action has no impact; for instance, even if someone were to cut off another person’s head, it would not take their life because the act would not alter the seven elements involved.

Sanjaya Belatthiputta

- He was known for his refusal to make definitive statements about anything, earning him a reputation for being evasive.

- For example, when asked about the existence of another world, he would respond in a way that neither affirmed nor denied it, maintaining a position of ambiguity.

The Samannaphala Sutta

Anna Titthhiya is a term used in Buddhist texts to refer to sects other than their own. The word Titthiya is derived from Tirthankara, which means "ford maker." This term is also used by Jains to refer to their teachers. In the Samannaphala Sutta of the Digha Nikaya, a dialogue discussing the benefits of becoming a renunciant, the influential contemporaries of the Buddha are listed.

- In this Sutta, Ajatashatru, the king of Magadha, is depicted sitting on his palace terrace, admiring the moonlit night with his ministers. He inquires about which renunciant or Brahmana they should invite for a discourse. The ministers suggest several names, including Purana Kassapa, Makkhali Gosala, Ajita Keshakambalin, Pakudha Kachchayana, Sanjaya Belatthiputta, and Nigantha Nataputta (Mahavira). These individuals are described as long-standing homeless wanderers, founders of sects, and leaders of their orders. However, the king is not impressed by these suggestions.

- At that time, the Buddha, accompanied by hundreds of bhikkhus, was staying at Jivaka’s mango grove near Rajagriha. Jivaka, Ajatashatru’s physician, suggests inviting the Buddha, and the king agrees. Ajatashatru poses a question to the Buddha, seeking to understand the benefits of leading the life of a renunciant, as he had not received satisfactory answers from others.

- The Buddha listens to Ajatashatru’s account of his conversations with the six thinkers and then provides a discourse on the subject that leaves the king completely satisfied. Other Buddhist Suttas also reference philosophical ideas prevalent at the time, with the Brahmajala Sutta mentioning 62 different philosophical positions regarding the world, the atman, causality, existence, and death. The conclusion of this Sutta is that these positions are mere opinions based on sensations and are not tenable. A Jain text, the Sthananga, also refers to various doctrines.

- The competitive nature among thinkers and their doctrines is evident in the accounts, with fierce debates where the losing side concedes defeat and joins the other. There are numerous instances of Buddhist monks who were initially followers of other teachers, such as Sariputta and Mahamoggallana, who were followers of Sanjaya Belatthiputta before joining the Buddhist sangha.

The Ajivikas

The Ajivika sect appears to be quite ancient, with references to predecessors of Makkhali Gosala, its most prominent leader. Besides Gosala, Buddhist tradition links Ajivika doctrines to Purana Kassapa and Pakudha Kachchayana. A. L. Basham (1951, 2003) has compiled and analyzed various scattered references to this sect.

- Jaina and Buddhist traditions provide accounts of Makkhali Gosala's birth and parentage, but these seem aimed at explaining his name and attributing a low social origin to him, lacking historical credibility. The Jaina Bhagavati Sutra states that his father, Mankhali, a mankha (likely a religious picture exhibitor and singer), and his mother, Bhadda, named him Gosala because he was born in a cowshed in Saravana village. Buddhaghosha's commentary on the Samannaphala Sutta also narrates Makkhali's cowshed birth but adds that he was a slave. The Bhagavati Sutra suggests that Makkhali initially followed his father's profession and later associated with Mahavira as a disciple, often depicted unfavorably in comparison to Mahavira.

- A core Ajivika belief was niyati (fate), which they believed determined and controlled everything. This doctrine was strictly deterministic, rendering human effort insignificant. While karma and transmigration were acknowledged, human effort had no role in them, as the paths for souls were preordained over thousands of years.

- The Ajivikas had regular meeting places known as sabhas for holding meetings and performing important ceremonies, indicating a corporate organization. They possessed canonical texts, with Buddhist and Jaina texts containing quotations or paraphrases from them. The Ajivikas practiced severe asceticism, often eating very little food, though Buddhists accused them of secret eating. They appeared to practice ahimsa (non-violence), but not as stringently as the Jainas, as the Bhagavati Sutra mentions their allowance of meat consumption. They also practiced complete nudity, and Jaina texts criticize them for not observing celibacy.

- The Ajivika sect was known for its non-discriminatory practices, welcoming individuals from all castes and classes into its fold. Its members included ascetics and laypeople from diverse backgrounds. For instance, a relative of King Bimbisara was a Kshatriya, while the ascetic Panduputta hailed from a lower social strata as the son of a wagon-maker. Makkhali Gosala, a prominent Ajivika figure, operated from the workshop of a woman potter named Halahala in Shravasti. The Ajivika order also garnered support from figures like Prasenajit, the king of Kosala, and included urban and trading groups among its laity.

- Buddhist and Jaina texts often criticized the Ajivikas, suggesting they were seen as formidable rivals. The Anguttara Nikaya features the Buddha condemning Makkhali Gosala as a harmful figure, comparing him to a fisherman causing destruction. This portrayal indicates the Buddhists viewed his teachings as particularly dangerous. Similarly, Jaina scriptures depict fierce conflicts between Gosala and Mahavira, highlighting the rivalry between the sects.

- Despite the criticism, the Ajivika sect remained influential in later centuries. The Mahavamsa implies their reach extended to places like Sri Lanka. Stories in the Divyavadana recount Ajivika fortune-tellers in royal courts, such as one predicting Ashoka's future prominence. Inscriptions from the Barabar and Nagarjuni hills document Ashoka and his successor Dasharatha dedicating caves to Ajivika ascetics. Ashoka’s edicts also reflect the sect's significance, urging officials to attend to various sects, including the Ajivikas. While the Maurya period may have marked the peak of the Ajivika sect, references to it persisted in sources well into the early medieval era.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on Cities, Kings, and Renunciants - 3 - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What were the primary urban occupations in early historical India? |  |

| 2. How did guilds function in early historical Indian society? |  |

| 3. What was the significance of trade in early historical India? |  |

| 4. Who were the Ajivikas, and what was their role in society? |  |

| 5. How did cities and kings interact with renunciants in early historical India? |  |