Cities, Kings, and Renunciants - 4 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

Early Buddhism

The Life of the Buddha

- The Pali canon describes the Buddha as an extraordinary man with a body bearing the 32 signs of a great person. He is known as the Tathagata, one who has come and gone thus, and has freed himself from the cycle of rebirth.

- The exact dates of the Buddha's life are debated. Some details of his life are in the Sutta and Vinaya Pitakas, but more connected accounts are found in later texts like the Lalitavistara, Mahavastu, Buddhacharita, and Nidanakatha, written in the early centuries CE.

- These later texts shaped the Buddha's life into a narrative with deep meanings for his followers, mixing historical facts with legends.

Birth and Early Life

- Born as Siddhartha, the Buddha was the son of Suddhodana, chief of the Sakya clan in Kapilavastu.

- His mother, Maya, gave birth to him in Lumbini while traveling to her parents’ home and died shortly after.

- Brahmanas (Brahmin priests) soon after his birth reportedly saw the 32 marks of a great man on his body.

- There are two types of mahapurusha (great man): a world conqueror or a world renouncer.

- Suddhodana, fearing his son would renounce the world, raised Siddhartha in a sheltered, luxurious environment.

- Siddhartha married Yashodhara, and they had a son named Rahula.

The Great Renunciation

- At the age of 29, Siddhartha encountered four sights that profoundly disturbed him: an old man, a sick man, a corpse, and a renunciant.

- These sights confronted him with the realities of old age, illness, and death, and the fourth sight introduced him to the path of renunciation.

- These experiences prompted him to leave his home and family in search of truth.

Searching for Enlightenment

- Siddhartha wandered for six years, learning from various teachers but remaining unsatisfied with their teachings.

- He joined five ascetics and practiced extreme austerities until his body was severely weakened.

- Realizing the need to nourish his body for peace of mind, Siddhartha shifted his approach.

- A young woman named Sujata offered him a bowl of milk-rice, providing the nourishment he needed.

Enlightenment

- Strengthened, Siddhartha sat under the pipal tree, vowing not to rise until he attained enlightenment.

- Different texts describe his path to enlightenment: some depict his gradual rise through meditative states, while others recount how Mara, a wicked being, tried to disrupt his meditation but failed.

- Eventually, Siddhartha achieved enlightenment and became known as the Buddha, the Enlightened One.

After his enlightenment, the Buddha remained in the same place for seven weeks, contemplating whether to share his profound experience. According to Buddhist tradition, it was only after the god Brahma urged him three times that he decided to teach others. The Buddha's first sermon on how to escape suffering was given to his five former companions in a deer park near Benaras, an event known as dhammachakka-pavattana, or the "turning of the wheel of dhamma." His first five disciples quickly understood the truth and became arhats, or enlightened beings. For over forty years, the Buddha traveled and taught his principles, establishing an order of monks and nuns called the sangha. He passed away at the age of 80 in Kusinara, which is believed to be modern-day Kasia.

The Buddha’s Teachings

Buddhism and Jainism: Philosophical Systems or Religions?

- Early Characterization: Initially, both Buddhism and Jainism were not religions in the conventional sense. They were seen as paths or ways of life with the potential for profound personal transformation.

- Link to Salvation: Their association with salvation, specifically deliverance from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, elevated them beyond ordinary philosophical systems.

- Target Audiences: The Buddha directed his teachings to both the monastic order and the laity. There were nuances in the teachings for each group, with some differences and overlaps.

- Four Noble Truths: The essence of the Buddha's doctrine is encapsulated in the Four Noble Truths:

- Suffering (dukkha): The acknowledgment that suffering is an inherent part of existence.

- Cause of Suffering (samudaya): Understanding the root causes of suffering.

- Cessation of Suffering (nirodha): The possibility of ending suffering.

- Path to Cessation: Following the Eightfold Path to achieve this goal.

- Eightfold Path: The Eightfold Path comprises interconnected activities related to knowledge, conduct, and meditation. It includes:

- Right View

- Right Intention

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

Importance of Meditation: Meditation plays a crucial role in Buddhism, serving as the key to achieving mental tranquility and insight. However, detailed guidance on meditative techniques is found in later Buddhist texts.

The Middle Path: The path taught by the Buddha is often referred to as the Middle Path, which strikes a balance between extreme indulgence and extreme asceticism.

Centrality of Dukkha: Dukkha, or suffering, is at the heart of the Buddha's teachings. He emphasized that all experiences are ultimately dukkha. This perspective can be viewed as either pessimistic or realistic.

Understanding Suffering: Suffering encompasses not only actual pain and sorrow but also the inherent potential for such experiences.

The Nature of Happiness and Suffering in Buddhism

- According to Buddhism, happiness or pleasure is not a stable state; it is temporary and depends on the satisfaction of our senses through specific objects or experiences.

- Suffering arises from fundamental human tendencies such as desire, attachment, greed, pride, aversion, and ignorance. Among these, desire (trishna) is central to both the cause and the cessation of suffering.

- The concept of impermanence (anichcha) is crucial in understanding this. Impermanence has various aspects, including the inevitability of old age, illness, and death in every individual’s life.

- At a more fundamental level, what we perceive as the 'I' or 'me' is actually a constantly changing assemblage of experiences and consciousness occurring in rapid succession.

The Concept of Self in Buddhism

- To illustrate this, the analogy of a river is often used: while the river appears constant, the individual drops of water that make it up are in a state of continuous change.

- In a later Buddhist text called the Milindapanha, a person’s name is described as a convenient label for a complex, interconnected cluster of constantly changing elements, much like a chariot composed of various parts such as the pole, axle, frame, and wheels.

- This understanding challenges the notion of a permanent, unchanging self, which is a result of misperception and ignorance.

- The emphasis on impermanence also entails the rejection of any eternal, unchanging substances or essences, such as the atman.

- In Buddhism, the elements of conscious existence are broadly categorized into nama (mind and mental factors) and rupa (form and body). Nama is further divided into four components: vedana (feelings arising from sensory contact), sanna (perception), sankharas (a complex group including knowledge derived from feeling and perception, and chetana, or will), and vinnana (cognition or conscious awareness).

- These four components of nama, along with rupa, make up the panchakhanda or the five aggregates, which constitute what we perceive as 'I' or 'me'.

The Law of Dependent Origination

- Another significant aspect of the Buddha’s teachings is patichcha-samuppada, the law of dependent origination. This law serves as both an explanation for all phenomena and a specific explanation for dukkha, or suffering.

- The elements of this law are often depicted as a wheel consisting of 12 nidanas, or links, each leading to the next in a chain of causation. These links include ignorance (avijja), formations (sankhara), consciousness (vinnana), mind and body (nama-rupa), the six senses (salayatana), sense contact (phassa), feeling (vedana), craving (tanha), and attachment.

- The cycle of existence, according to Buddhism, involves several stages: (upadana), becoming (bhava), birth (jati), and old age and death (jara- marana). The nidanas were later grouped into three categories related to past, present, and future lives, illustrating that the origins of rebirth lie in ignorance.

Nibbana: The Ultimate Goal

- Nibbana, the ultimate goal of the Buddha’s teachings, is not a physical place but an experiential state that can be achieved in this life.

- It signifies the extinction of desires, attachments, greed, hatred, ignorance, and the sense of self.

- Terms like vimokha, vimutti, and arahatta also convey similar meanings of freedom and emancipation, indicating a release from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

- Nibbana should not be confused with physical death; parinibbana refers to the death of an enlightened being, such as the Buddha, marking the final extinction of their physical existence.

Transmigration in Buddhism

- Buddhism acknowledges the concept of transmigration (samsara) but denies the existence of the atman, or eternal self.

- Instead, it suggests the transmigration of character or personality, or the transmission of a life impulse, akin to transferring a flame from one candle to another.

- Upon death, the elements of conscious existence do not vanish but reappear in a different combination and form in another time and place.

- The Milindapanha provides an analogy, comparing transmigration to milk transforming into curds, butter, and ghee, emphasizing that a being is neither the same nor entirely different in the process of transmigration.

The Buddhist Universe and Rebirth

- In the Buddhist cosmology, there are numerous worlds and various kinds of beings, and one can be reborn as any of them.

- The connection between different lives is established through karma.

- Unlike the Brahmanical tradition where karma refers to ritual actions, in Buddhism, karma pertains to intentions that lead to actions of body, speech, or mind.

- Rebirth is determined by the cumulative results of karma from a particular life.

Ethical Code of Conduct

- The Buddha prescribed an ethical code of conduct for both monastic members and laypeople.

- Monks and nuns are expected to strictly observe the following precepts:

- Destruction of life

- Taking what is not given (theft)

- Sexual activity

- Lying

- The use of intoxicants

The Analogy of the Raft

- In the Majjhima Nikaya, the Buddha uses the analogy of a raft to illustrate that the dhamma (teachings) he provided is a means to an end. Once the goal is achieved, there is no need to cling to the means.

- The analogy describes a man on a journey who encounters a dangerous river with no way to cross. He builds a raft to safely reach the other side. After crossing, he realizes the raft was essential for his journey.

- However, it would be inappropriate for him to carry the raft on his back or head after crossing. Instead, he should either beach it or sink it in the water and continue on his way.

- Similarly, the Buddha teaches that dhamma is meant for crossing over obstacles, not for clinging to. Those who understand this will let go of even the teachings and practices, realizing their purpose is to aid in crossing over, not to be held onto.

Buddhist Ethics and Ahimsa

- The Buddhist principle of ahimsa (non-violence) was a critique of Brahmanical animal sacrifices.

- Monks and nuns were prohibited from killing animals and drinking water that contained small living creatures.

- However, ahimsa did not require strict vegetarianism. Monks could eat meat if it was offered to them, as long as the animal was not killed specifically for them.

- Certain types of flesh, such as that of humans, elephants, snakes, dogs, and horses, were never to be accepted.

- Righteous actions are necessary but not sufficient for attaining nibbana (enlightenment). The ultimate state is beyond ordinary experiences and moral distinctions.

The Buddha's Authority and the Role of Gods

- Buddhism is often seen as a rational doctrine, but the Buddha is presented as the ultimate source of knowledge, with the possibility of others equals him being remote.

- The Buddha sometimes performs miracles to convince stubborn adversaries.

- Gods such as Brahma and Sakka (Indra) are present in Buddhism, but they cannot help humans attain nibbana. Only by following the path laid down by the Buddha can this goal be achieved.

The Buddhist Sangha and the Laity

Establishment of the Monastic Order:

- The monastic order of monks, and later nuns, was established during the Buddha's lifetime.

- This creation allowed the Buddha's followers to forge a distinct identity within the broader community of renunciants.

- The Buddhist sangha became a fundamental institution and played a crucial role in spreading the Buddha's teachings.

Vinaya Pitaka:

- The Vinaya Pitaka provides an account of the sangha's establishment and the rules governing it, although this account may not be strictly historical.

- The order of monks and nuns was possibly inspired by existing sangha polities.

Sections of the Vinaya Pitaka:

- Sutta Vibhanga: Contains the Patimokkha, a set of monastic rules for monks (227) and nuns (311).

- Khandaka: Includes the Mahavagga and Chullavagga, detailing monastic rules and stories from the Buddha's life.

- Appendix (Parivara): An appendix to the Vinaya Pitaka.

Details in the Vinaya Rules:

- The Vinaya rules cover various aspects of monastic life, including eating, walking, talking, clothing, and behavior.

- They also address the corporate life of the sangha, including dispute resolution.

Purpose of the Rules:

- The rules aimed to regulate individual conduct, preserve the unity of the sangha, and define relations between the sangha and laity.

Early Sangha Life:

- Some scholars, like Sukumar Dutt, suggest that early monks were wanderers who later settled down, with the institution of the monsoon retreat (vassavasa) marking this transition.

- This retreat, observed by Jainas and other ascetic orders, involved staying in one place during the rainy season.

Development of Monastic Establishments:

- Temporary retreats of monks may have evolved into permanent monastic establishments known as viharas.

- However, other scholars, like Mohan Wijayaratne, argue that the life of the Buddhist sangha was both itinerant and sedentary from the beginning, with lay followers donating land and building monasteries even during the Buddha's lifetime.

- Permanent monastic communities (viharas or aramas) likely emerged early, necessitating rules and regulations to govern these communities.

Monastic Life

The pravrajya ceremony marked the transition of an individual from home to homelessness, signifying their initiation as a novice under a preceptor. This ceremony involved shaving the head and wearing ochre robes. During the ceremony, the novice recited the formula for taking refuge in the Buddha, dhamma, and sangha, followed by the acceptance of the 10 vows. The upasam-pada ceremony was the formal ordination event where the novice became a full-fledged member of the monastic community. Monastic Life in Buddhism Early Buddhism, also known as Nikāya Buddhism, refers to the earliest phase of Buddhist history, which is characterized by the formation of the monastic community (sangha) and the laying down of the foundational teachings of the Buddha. The monastic life during this period was guided by the Vinaya Pitaka, a scripture that contains rules and regulations for monks and nuns. Authority and Discipline in Monastic Communities Monastic communities were led by senior monks who held authority within the group. Members of the sangha living in a locality were expected to gather every fortnight on the new moon and full moon days, known as uposatha days, to recite the Patimokkha rules and confess any breaches. The Patimokkha, found in the Vinaya Pitaka, outlines serious and less serious breaches of monastic discipline. There were various offenses that required consequences, ranging from confession of guilt to expulsion. The four most serious offenses, known as parajika or defeat, leading to expulsion from the sangha included:

- Sexual intercourse

- Taking what is not given

- Killing someone

- Making false claims of spiritual attainment

Relationship between Sangha and Laity

The Buddha’s followers had the option to join the sangha or remain outside it. The sangha and laity had a close relationship, with members of the sangha teaching the dhamma to the laity and serving as examples of righteous living. The monastic community relied on the laity for food and other forms of support. For the laity, dana, or giving, was an important activity believed to lead to the accumulation of merit, as it involved generosity and detachment from material possessions. Interaction between monks and laity occurred in various contexts, with the most common being monks’ begging rounds for food. Monks were expected to give discourses to the laity and attend significant events in their lives when invited. Permanent monastic establishments likely strengthened the bonds between the two groups, but a certain distance was always maintained. Lay Followers and Conduct

According to tradition, the first lay followers of the Buddha were two merchants, Tapassu and Bhallika, followed by a swift expansion of lay followers, including male (upasakas) and female (upasikas) followers. An upasaka or upasika is a person who has taken refuge in the Buddha, dhamma, and sangha but has not taken monastic vows. Good conduct for the laity involved adhering to the five vows, which are:

- Not harming living beings

- Not taking what is not given

- Avoiding sexual misconduct

- Not indulging in false speech

- Not consuming intoxicants

On certain occasions, such as full moon days or for extended periods, a layperson could adopt the modified eight vows, which included replacing the vow of avoiding sexual misconduct with sexual abstinence and taking additional vows such as not eating after mid-day, avoiding entertainments, refraining from using jewelry or perfumes, and not sleeping on luxurious beds. By following these modified vows, laypersons could narrow the gap between themselves and monastic discipline.

According to Buddhist texts, there are examples of knowledgeable laypeople, and in some cases, lay individuals, like the Buddha's father, attained arhatship just by hearing the doctrine without formally joining the sangha.

The Sigalavada Sutta outlines the duties of the laity, highlighting the importance of fulfilling responsibilities in key social relationships, including those between parents and children, teachers and pupils, husbands and wives, friends and companions, masters and servants, and shramanas and Brahmanas.

The Mahamangala Sutta in the Samyutta Nikaya emphasizes a man's duties towards his parents, wife, and children, stressing the need for a husband to be faithful, respectful, and considerate of his wife's feelings.

The Anguttara Nikaya recounts the Buddha's guidance to Anathapindika's challenging daughter-in-law, illustrating acceptable and unacceptable behavior for a wife.

In later centuries, evidence from texts, archaeology, and inscriptions contributes to the understanding of the sangha and laity. Over time, pilgrimages to stupas and sacred sites also facilitated interaction between the laity and the sangha. However, there is a disparity in knowledge, with more information available about the bhikkhu sangha (monk community) compared to the bhikkhuni sangha (nun community).

The Social Implications of the Buddha’s Teachings

The Buddha is often seen as a social reformer or even a revolutionary who opposed social discrimination and advocated for equality. However, a closer examination of the Pali texts presents a more nuanced view. While the Buddha’s teachings were indeed more socially inclusive than the Brahmanical tradition, they did not intend to eliminate social differences entirely.

The Buddha perceived all social relationships as bonds that caused suffering, and believed that liberation could only be achieved by breaking free from these bonds. The establishment of the monastic order had the potential to create significant social change by offering refuge to those on the fringes of society.

Despite this, the Buddhist tradition aimed to preserve the existing social order and imposed certain conditions for entry into the monastic community. For example:

- Soldiers needed royal permission to join.

- Slaves could only join after gaining freedom from their masters.

- Debtors had to settle their debts before entering the monastic community.

Unlike the Brahmanical tradition, which viewed varna (social class) as divinely sanctioned, the Buddhist tradition considered it a human-made classification. The Buddha, in the Anguttara Nikaya, illustrated this by describing a dream where birds of different varnas gathered at his feet, symbolizing the inclusion of monks from all varnas—Khattiya (warriors), Brahmana (priests), Vessa (traders), and Sudda (laborers)—into his fold.

Joining the sangha (monastic community) was supposed to render varna and jati (birth) irrelevant. However, an analysis of the actual composition of the sangha reveals a significant number of upper-class members. Many monks were Brahmanas or Kshatriyas, including those from Kshatriya clans known as ganas, and individuals from high-status families (uchcha kulas) were more common than those from lower backgrounds (nicha kulas).

Notable monks from the Brahmana class included Sariputta, Mahamoggallana, and Mahakassapa, while prominent Kshatriya monks included the Buddha, Ananda, and Aniruddha. Upali, a distinguished monk, originally came from a lowly background as a barber among the Sakyas.

The Pali canon inverts the Brahmanical hierarchy, placing Kshatriyas above Brahmanas. The term ‘Brahmana’ in Buddhist texts has dual meanings: it refers to a social category and an ideal category denoting a wise person leading an exemplary life. In some instances, the Buddha himself is called a ‘Brahmana’. The Sonadanda Sutta emphasizes that true Brahmanahood is not inherited; it is based on knowledge rather than mere recitation of Vedic verses. While the Buddha critiques Brahmanas, he also acknowledges wealthy and influential Brahmanas who have substantial followings.

The Ambattha Sutta

- The Buddha and his monks were travelling through the Kosala region when they stopped at a Brahmana village called Ichchanakala. There, a Brahmana named Pokkharasadi, living on land granted to him by King Prasenajit, sent his pupil Ambattha to check if the Buddha had the 32 signs of a great man.

- When Ambattha met the Buddha, he was rude and fidgety, leading to the Buddha admonishing him. Ambattha claimed the superiority of the Brahmanas, criticizing the Buddha's lineage and the Sakya people. He recounted his visit to Kapilavastu, where he felt disrespected by the Sakya assembly.

- This prompted the Buddha to question Ambattha about his lineage, to which Ambattha replied that he was from the Kanhayana gotra. The Buddha then shared the story of the Sakyas and Kanhayanas, highlighting the superiority of his lineage. The Sakyas were descendants of a king's banished children, while the Kanhayanas descended from a slave girl’s son.

- The Buddha's point forced Ambattha to concede the superiority of the Sakya lineage. The Buddha softened the blow by praising Ambattha's ancestor, Kanha, as a great sage. He quoted a verse emphasizing that true worth comes from wisdom and righteousness, not lineage.

The Buddha's Encounter with Ambattha and Pokkharasadi

- Buddha's Discourse: The Buddha highlighted to Ambattha that no matter how esteemed Brahmana Pokkharasadi considered himself, he was insignificant compared to King Prasenajit, who had granted him his land. While Brahmanas focused on reciting and memorizing ancient verses, their luxurious way of life was a stark contrast to that of the early sages.

- Ambattha's Observation: Ambattha noticed the 32 physical marks of a great person on the Buddha and reported this to Pokkharasadi, who decided to meet the Buddha himself.

- Meeting the Buddha: When Pokkharasadi met the Buddha, he also observed the same auspicious signs and invited the Buddha and his followers for a meal. During this occasion, the Buddha gave a discourse that deeply impressed Pokkharasadi.

- Conversion: As a result of the Buddha's teachings, Pokkharasadi declared himself, his family, and his disciples as followers of the Buddha.

Brahmanas Joining the Buddha's Teachings

- Participation Despite Criticism: The large-scale involvement of Brahmanas as monks and lay-followers of the Buddha, despite his criticism of Brahmanical rituals and claims to social superiority, can be attributed to several factors.

- Resonance of Teachings: The Buddha's teachings may have resonated with ongoing debates and discussions within the Brahmana intellectual community. Not all Brahmanas were ritual specialists, and those who were not might not have taken offense to the Buddha's critique of sacrifice.

- Disapproval from Peers: Brahmanas joining the Sangha were likely viewed with disapproval by other Brahmanas, as indicated by the responses of Vasettha and Bharadvaja in the Agganna Sutta when the Buddha asked about the reactions of their community to their joining the order.

- Acceptance of Alms: The practice of bhikkhus accepting food from everyone, regardless of class or caste, reflected a deliberate disregard for contemporary social norms. The Buddha himself had no restrictions on accepting food and would dine with people across the social hierarchy, including his last meal at the home of a blacksmith named Chunda.

- Notion of Status in Pali Texts: Despite the apparent disregard for social status, Pali texts like the Vinaya Pitaka recognized high and low occupations. High sippas included money changing, accounting, and writing, while low sippas encompassed professions like leather making, reed working, potting, tailoring, painting, weaving, and barbering. High occupations were considered to be farming, cattle rearing, and trade. Buddhist laity were prohibited from engaging in trade involving weapons, meat, intoxicants, or poisons.

- In worldly matters, birth and family were significant, but there was also a strong belief that deeds were more important. In the Samyutta Nikaya, when the Brahmana Sundarika asked the Buddha about his origins, the Buddha replied, "Do not ask about the origin (jati), ask about the behavior. Just as fire can come from any wood, a saint can be born in a family of low status." He further emphasized that a person becomes a Brahmana not by birth, but by their actions. Birth in a high or low family is often seen as the result of actions from previous lives, but the potential to achieve nibbana is present in everyone.

- The Buddhist view on varna and birth is clearly expressed in texts like the Ambattha Sutta in the Digha Nikaya. Here, it is stated that the Kshatriya is superior to the Brahmana in terms of worldly social status, but the one who has attained nibbana is superior to all.

- The Buddha's dhamma likely appealed to the laity because it provided a coherent code of conduct that resonated with the times. The positive view of emerging affluent groups recognized their status and importance. The laity, especially those who made generous donations, included Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, gahapatis, and members of both high and low families. Kshatriya patrons included powerful kings like Bimbisara, Ajatashatru, and Prasenajit. Buddhist texts placed gahapatis in a high social position, and they were among the most significant lay supporters of the sangha. Their importance is highlighted by instances where prominent monks, including the Buddha, visited some of them on their deathbeds, an honor typically reserved for members of the sangha.

Buddhism and Women

- Early Buddhism had two significant aspects: the belief that women could attain nibbana, the highest goal, and the establishment of a bhikkhuni sangha. However, Buddhist texts also portray stereotypical ideals of women as submissive and obedient, with their lives centered around husbands and sons. Additionally, these texts contain negative portrayals of women as temptresses and beings driven by passion, likening them to poisonous snakes and fire, warning against them. This reflects the tradition's emphasis on celibacy and viewing women as a potential threat. Just as monks were cautioned about women, nuns were advised to be wary of men.

- According to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha was initially reluctant to establish a bhikkhuni sangha but eventually agreed due to the persistent requests of his disciple Ananda and his aunt Mahapajapati Gotami. The Vinaya Pitaka records the Buddha predicting a decline in the doctrine's longevity from 1,000 to 500 years because of the inclusion of women in the sangha.

Patachara's Song

- Patachara was born into a wealthy banking family in Shravasti. After marrying and losing her two children, she became a wandering ascetic and joined the sangha. In her song, Patachara expresses her deep longing for nibbana, leading up to the moment she finally experiences it.

- Young Brahmanas achieve prosperity by diligently ploughing their fields, sowing seeds, and caring for their families. Despite following my teacher's rules and not being lazy or proud, I wonder why I haven't found peace. As I bathed my feet, I observed the water flowing down the slope. I focused my mind like training a good horse. Taking a lamp into my cell, I checked the bed and sat down, using a needle to push the wick down. When the lamp extinguished, my mind was liberated.

The Eight Conditions Imposed on Nuns

As per the Vinaya Pitaka, nuns who joined the Buddhist order were required to follow eight important conditions throughout their lives.

1. Respect for Monks

- A nun, regardless of her length of ordination, must show respect to a monk, even if he has been ordained just that day.

- This includes rising from her seat, saluting him with joined hands, and demonstrating deference.

2. Monsoon Retreat

- A nun is not allowed to spend the monsoon retreat in a district where there are no monks present.

3. Fortnightly Duties

- Every fortnight, a nun must inquire from the monks about the date of the uposatha ceremony and request them to preach the doctrine.

4. Triple Invitation

- At the end of the monsoon retreat, a nun is required to address the "triple invitation" to both the order of monks and nuns.

- This involves asking if anyone has seen, heard, or suspected anything against her.

5. Serious Offence Procedure

- A nun who has committed a serious offence must undergo the manatta discipline, a form of temporary probation, before both orders.

6. Ordination Requirements

- A postulant must follow the six precepts (the five lay vows plus the additional vow of not eating after noon) for two years before seeking ordination from both orders.

- In contrast, monks can be ordained at any time they are ready, provided they are at least 20 years old.

7. Conduct Towards Monks

- A nun is prohibited from reviling or abusing a monk under any circumstances.

8. Admonition and Advice

- Monks have the authority to give admonition and advice to nuns, but nuns are not allowed to do the same to monks.

Additional Notes on the Sangha

- The sangha was not open to certain groups of women, including pregnant women, mothers of unweaned children, rebellious women associating with young men, and those lacking permission from their parents or husbands to join.

- While the rules for nuns were similar to those for monks, there were more regulations for nuns.

- The Buddha is said to have established eight special rules that subordinated nuns to monks, though some suggest this was a later addition.

- Although women could achieve salvation, the concept of them attaining Buddhahood directly without first being reborn as men was not accepted.

Learned Nuns in Buddhist Texts

- Buddhist texts reference several knowledgeable nuns, such as Khema, who impressed King Pasenadi with her discourse, leading him to bow before her.

- Dhammadinna Theri is another example; when the Buddha heard her answers to questions from the laywoman Visakha, he praised her wisdom and knowledge, stating he would have given the same answers if asked.

The Therigatha

The Therigatha is a collection of 73 poems with 522 verses, written by 72 nuns who achieved a high level of spiritual attainment. Many of these nuns are described as possessing tevijja, the three kinds of knowledge, an attribute of arhats. Some poems express the nuns’ experience of nibbana and their experiences before joining the sangha, ranging from unhappy marriages to tragedies like the death of a child. One story is about Chanda, a young girl from a Brahmana family, who became destitute when her parents died in an epidemic. A nun named Patachara helped her by providing food, teaching her the doctrine, and initiating her into the order.

Interaction between Monks and Nuns

- Monks and nuns had some interaction, but it was regulated and restricted.

- Nuns were required to live not too far away from monks during regular times and the monsoon retreat.

- Nuns had to consult monks for the date of the uposatha ceremony.

- If a nun broke certain rules, she had to answer to a mixed gathering of monks and nuns.

- A monk was not allowed to be alone with a nun in a closed room or preach to a woman in private without the presence of a third person who could understand.

- However, a monk could accompany a nun on a road considered dangerous.

The Seven Kinds of Wives

The Buddha, during a visit to Anathapindika's home, encountered a noisy situation caused by Sujata, the daughter-in-law. She was wealthy but unruly, refusing to listen to anyone. Anathapindika sought the Buddha's advice for her.

In response, the Buddha described seven types of wives, some commendable and others not:

1. The Slayer Wife

- Characterized by cruelty and lack of compassion.

- Engages in murderous behavior, neglects her husband at night.

- Spends time with others and is acquired through money.

2. The Thief-like Wife

- Takes her husband's money with the intention of ruining and impoverishing him.

3. The Mistress-like Wife

- Exhibits laziness and a penchant for luxury.

- Expensive to maintain, enjoys gossiping, and speaks in a loud, harsh voice.

- Diminishes her husband's enthusiasm and productivity.

4. The Mother-like Wife

- Cares for her husband and his property as a mother would her only son.

5. The Sister-like Wife

- Treats her husband with respect, similar to how a younger sister regards her older brother.

6. The Companion-like Wife

- Comes from a good background, remains faithful to her husband.

- Welcomes him with joy, akin to reuniting with a long-lost friend.

7. The Slave-like Wife

- Exhibits calmness, patience, and obedience.

- Accepts her husband’s mistreatment meekly.

- The Buddha explained that the first three types of wives face dire consequences after death, while the latter four are destined for better fates.

- After hearing this, Sujata resolved to embody the qualities of a slave-like wife.

- Whether this incident is factual or not is not crucial. It illustrates a spectrum of possible husband-wife dynamics. Sujata's initial portrayal as a less-than-ideal wife suggests the existence of similar women. Her eventual choice of the most subservient role reflects the ideal wife image held by the men who created these texts. However, it is noteworthy that various forms of husband-wife relationships are contemplated in these narratives.

Progressiveness of Tradition

- The progressiveness of a tradition should be evaluated based on the standards of its own time.

- In the context of the 6th/5th century BCE, the Buddha provided a significant opportunity for women's spiritual aspirations.

- When compared to texts from other religious traditions, women are notably more visible in Buddhist texts.

- In later centuries, women, including bhikkhunis and upasikas, were prominent as donors at Buddhist stupa-monastery sites.

- However, after its inception, the bhikkhuni sangha appears to be less prominent in the available historical sources.

Early Jainism

The Jaina Tirthankaras: Vardhamana Mahavira

- Jainism is believed to be older than Buddhism, but its exact age is hard to determine. The Buddha and Mahavira (the 24th Tirthankara) lived around the same time and shared some ideas, like rejecting the Veda's authority and emphasizing renunciation for salvation. However, their philosophical views had significant differences.

- Jain Concept of Time: Jainism views time as an endless cycle of progressive (utsarpinis) and regressive (avasarpinis) phases, each divided into six stages called kalas. There are 24 Tirthankaras in each half-cycle.

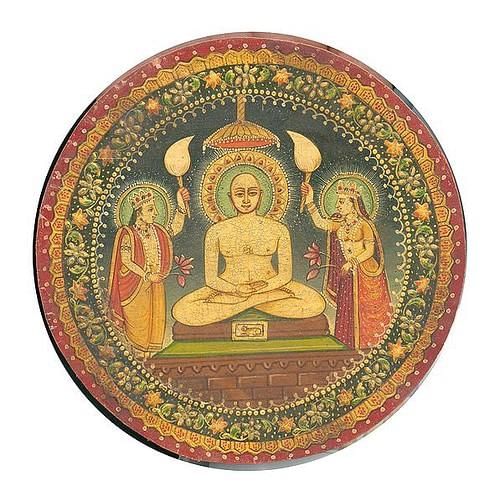

- Tirthankaras: Rishabhadeva is the first Tirthankara in our current avasarpini cycle. The historicity of Tirthankaras is debated, but Neminatha, Parshvanatha, and Mahavira are notable figures. Mahavira, known as the great hero, is believed to have taught the same doctrine as other Tirthankaras.

- Characteristics of a Jina: A Jina is a human with extraordinary insight and knowledge, born with unique traits like an adamantine body and psychic powers such as avadhijnana, allowing them to perceive distant objects and foresee future events.

- Sectarian Division: By around 300 CE, the Jaina community split into two sects: the Digambara (sky-clad) and the Shvetambara (white-clad). Both sects have different hagiographies of Vardhamana Mahavira, which share some similarities but also contain discrepancies. Extracting a clear historical account of Mahavira's life from these hagiographies is as challenging as it is for the Buddha.

- Jainism is one of the ancient religions of India and is known for its unique beliefs and practices. At the core of Jain philosophy is the idea of Ahimsa or non-violence, which is considered the most important principle. Jains believe that all living beings have a soul and that harming any living being, even unintentionally, leads to negative karma. This belief in non-violence extends to all aspects of life, including food, clothing, and even the environment.

- The Jains believe that the universe is eternal and has no beginning or end. It is inhabited by an infinite number of living beings, both in the form of souls and in material bodies. The souls in the universe are considered to be pure and possess infinite knowledge, power, and bliss. However, they are also subject to the influence of karmic matter, which attaches itself to them and causes them suffering. This cycle of birth, death, and rebirth continues until the soul is liberated from the karmic bondage.

- The Jain community is divided into two main sects: the Digambaras and the Shvetambaras. The Digambaras believe that women cannot attain liberation without being reborn as men, while the Shvetambaras believe that women can achieve liberation in their own right. Both sects share the same core beliefs, but differ in their interpretations of certain texts and practices.

Mahavira and his Life

- Mahavira, also known as Vardhamana, was born around 599 BCE in Kundagrama, near Vaishali, the capital of Videha. Like the Buddha, he came from an aristocratic Kshatriya background. His father, Siddhartha, was the chief of the Jnatri clan, and his mother, Trishala, was the sister of the Videha king.

- According to the Shvetambara tradition, Mahavira was originally conceived by a Brahmana named Rishabhadatta, but the embryo was transferred to Trishala's womb by Shakra (Indra) because a Brahmana woman or one from a low family was deemed unworthy of giving birth to a future tirthankara.

- Even before his birth, Mahavira is said to have shown extraordinary concern for ahimsa (non-injury). He remained absolutely still in his mother’s womb to avoid causing her discomfort and moved slightly to reassure her when he sensed her fear. According to the Shvetambara tradition, he vowed not to renounce the world as long as his parents were alive.

Early Life and Family

- The Acharanga Sutra describes Mahavira’s parents as followers of Parshvanatha, another jina. According to the Shvetambara tradition, Mahavira married Yashoda and had a daughter named Priyadarshana. However, the Digambara tradition holds that he never married.

Renunciation and Austerities

- Mahavira is believed to have renounced the world at the age of 30. The Shvetambara tradition claims he did so after his parents’ death, while the Digambara tradition states he sought their permission to renounce while they were still alive. Both traditions agree that he wandered for about 12 years, practicing severe austerities, including meditation and fasting.

Enlightenment

- Mahavira is said to have attained kevalajnana (infinite knowledge, omniscience) near the town of Jrimbhikagrama, on the banks of the Rijupalika river, in the field of a householder named Samaga.

Post-Enlightenment Life

- According to the Digambara tradition, upon attaining enlightenment, Mahavira was freed from ordinary human defects such as hunger, thirst, sleep, fear, and disease.

- He no longer engaged in mundane activities and sat fixed and omniscient in a lotus posture in an assembly hall created by the gods. A divine sound emanated from his body, and beings from various realms listened attentively.

Dissemination of Teachings

- The task of spreading Mahavira’s teachings was entrusted to the ganadharas (chief disciples), starting with Indrabhuti Gautama and his brothers. The number of ganadharas soon expanded to 11, all of whom were Brahmanas.

- This tradition indirectly created the order of monks, nuns, and laity. In contrast, the Shvetambara tradition describes Mahavira as actively traveling and teaching his doctrine.

Death and Legacy

- Both traditions agree that Mahavira died at Pava (modern Pavapuri near Patna) at the age of 72 and became a siddha (fully liberated and free from embodiment). The traditional date of his passing is 527 BCE, marking the beginning of the Vira-nirvana era.

The Jaina Perspective on Reality

- The Jaina critique of other philosophical systems is that their statements about reality—such as whether it is eternal or non-eternal, changing or unchanging—represent a single, partial, and extreme view.

- Other schools' views are not deemed completely invalid but are seen as partial truths (nayas) that cannot claim absolute validity.

- Jaina doctrine asserts that reality is manifold (anekanta) and that everything that exists (sat, i.e., being) has three aspects: substance (dravya), quality (guna), and mode (paryaya).

- The doctrine of anekantavada emphasizes the complexity and multiple aspects of reality.

- Anekantavada and syadavada (the doctrine of maybe) highlight the relativity of all knowledge.

- Syadavada suggests that every judgment is relative to the specific aspect of the object being judged and the perspective from which it is judged, meaning no judgment is true without qualification.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on Cities, Kings, and Renunciants - 4 - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What were the main features of urban occupations in early historical India? |  |

| 2. How did trade and traders influence the economy of early historical India? |  |

| 3. What were the key beliefs of the Ajivikas in early historical India? |  |

| 4. How did early Buddhism and early Jainism differ in their approach to renunciation? |  |

| 5. What role did cities play in the relationship between kings and renunciants in early historical India? |  |