Cultural Transitions: Images from Texts and Archaeology, c. 2000–600 BCE - 3 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Pottery from Late Harappan Levels, Bhorgarh, Delhi |

|

| Recent Discoveries |

|

| The Copper Hoards |

|

| Copper Hoard Objects |

|

| Neolithic-Chalcolithic Settlements in South India |

|

Pottery from Late Harappan Levels, Bhorgarh, Delhi

The late Harappan pottery discovered in Bhorgarh, Delhi, is crafted from well-processed clay and encompasses both handmade and wheel-made varieties, featuring a range of coarse to fine fabrics. These pottery pieces are characterized by a thin cream wash or a vivid red slip, adorned with geometric and naturalistic designs painted in black. Some pots also exhibit incised patterns. Alongside pottery, various artefacts such as chert blades, stone querns, pestles, and bone points were found.

- Copper objects were also unearthed, including a broken blade from Alamgirpur, a fragmentary chisel, and rings from Bargaon.

- Ornaments like bangles made of terracotta, carnelian, and steatite, as well as beads of terracotta, steatite, agate, carnelian, and faience, were among the findings.

- Additionally, circular and triangular terracotta cakes, animals, carts, and wheels made of terracotta were discovered.

Agricultural Continuity

- The evidence suggests that the inhabitants of these sites continued to cultivate crops such as wheat and barley, which were present in the area during the mature Harappan phase.

- Furthermore, rice husk was found embedded in the cores of potsherds at Hulas and Un, indicating the cultivation of rice as well.

- The range of plant remains found at late Harappan Hulas is extensive and includes various types of wheat (dwarf, bread, and club), oats, jowar (sorghum), ragi (finger millet), lentils, field peas, grass peas, moong (green gram), chickpeas, a broken cowpea, as well as cotton, castor, almond, walnut, fruits, and wild grasses.

- This diverse array of plant remains indicates that the community was agricultural with a well-established and varied agricultural base.

Recent Discoveries

The Sanauli Cemetery

- Excavations at Sanauli, located in the Baghpat district of Uttar Pradesh, India, have uncovered what appears to be a large late Harappan cemetery, although the excavators prefer to classify it as mature Harappan.

- The site, dated tentatively to around 2200–1800 BCE, exhibits both similarities to other mature or late Harappan sites and distinct features of its own.

Excavation Details

- Conducted by D. V. Sharma and his team.

- 116 graves have been excavated so far, laid in a northwest–southeast orientation.

Types of Burials

- Extended Burials: 52 graves with extended bodies.

- Secondary Burials: 35 graves where remains were reburied.

- Symbolic Burials: 29 graves without human remains, likely symbolic.

Notable Burials

- Double Burial (Burial 27): Two male skeletons aged 30–35 years with grave goods including steatite beads, a dish-on-stand, and pottery.

- Triple Burial (Burial 69): Included urn burials and a skull placed upside down, with various pottery types.

- Symbolic Burials:Burial 28: Featured copper objects and a violin-shaped container with stylized copper pieces. Burial 106: Contained steatite inlays resembling a human effigy.

Other Finds

- Copper objects, gold ornaments, semi-precious stone beads, and glass items found in various graves.

- Evidence of animal sacrifice in some burials.

- A burnt clay trough, possibly used for cremation, found at middle levels of the site.

The significance of the Dish-on-Stand

- In the context of grave goods, the dish-on-stand held considerable importance. Its design underwent changes over time, and the unique mushroom shape observed in the upper levels of burials is not found in other contexts.

- Typically, in most burials, the dish-on-stand was placed either below the hip or near/below the head of the deceased. However, there were a few instances where it was positioned close to the feet.

- Additionally, the dish-on-stand was used for offering purposes, as seen in one case where it held the head of a goat.

Skeleton Analysis by S. R. Walimbe

- S. R. Walimbe conducted a preliminary study of approximately 40 skeletons and identified the remains of 10 males and 7 females.

- The sex of 17 skeletons could not be determined.

- Five child burials were analyzed, revealing the ages of the children: one aged 1–2 years, two aged 3–5 years, and two around 10 years old.

- Additionally, remains of six sub-adults were found.

The presence of such a remarkable cemetery suggests an association with a large habitation site, although this site has not yet been identified.

Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP)

- The Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP) was first discovered in western Uttar Pradesh during the years 1950–51 at sites like Bisauli in Badaun district and Rajpur Parsu in Bijnaur district. This pottery is characterized by being ill-fired, wheel-made, with a fine to medium fabric, and often features a thick red slip, occasionally adorned with black bands. Some pieces of this pottery display incised designs and post-firing graffiti.

- The pottery earned its name because it leaves an ochre color on the fingers when rubbed, a phenomenon that could result from factors like water-logging, wind action, poor firing, or a combination of these.

Distribution and Variants

- Initially, OCP was found to be widely spread across the doab region, particularly in districts such as Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Meerut, and Bulandshahr in western Uttar Pradesh. Over 80 sites have been identified in Saharanpur district alone.

- The distribution of OCP extends beyond this area, with findings from Bahadarabad near Hardwar in Uttar Pradesh to Noh and Jodhpura in Rajasthan, and from Katpalon near Jullundar in Punjab to Ahichchhatra near Bareilly. Notably, the OCP phase in Rajasthan appears to be earlier than that in the doab.

- OCP is found in different stratigraphic contexts, such as:

- At sites like Hastinapura, Ahichchhatra, and Jhinjhana, OCP levels were followed by a break in occupation and a subsequent Painted Grey Ware (PGW) level.

- At sites like Atranjikhera and Noh, OCP levels were followed by a Black and Red Ware (BRW) level, and then a PGW level.

- Certain sites such as Bargaon and Ambakheri show an overlap between the late Harappan and OCP phases.

- Scholars debate whether OCP is a degenerate form of late Harappan pottery or an independent ceramic tradition influenced by Harappan pottery in some areas. Two broad categories of OCP are identified:

- Western Zone : Sites like Jodhpura, Siswal, Mitathal, Bara, Ambakheri, and Bargaon, showing links with the Harappan tradition.

- Eastern Zone : Sites like Lal Qila, Atranjikhera, and Saipai, which do not display such links.

The Copper Hoards

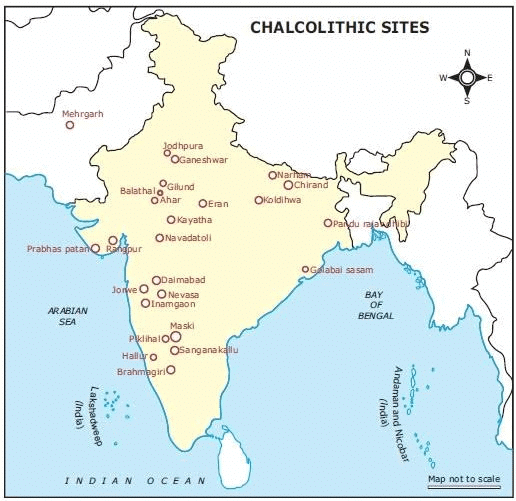

Discovery and Distribution

- The first copper harpoon was found in 1822 at Bithur in Kanpur district, leading to the discovery of over 1300 similar copper objects across India.

- These objects, mostly found in hoards, are referred to as copper hoards by archaeologists.

- Copper hoards have been identified at around 90 sites, spanning from the upper Ganga valley to Bengal and Orissa.

- Significant finds have also occurred in Haryana, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, with the highest concentration in the doab region of Uttar Pradesh.

Site Variability

- The number of objects found in a single hoard varies widely, from 1 to 47.

- An exceptional case is Gungeria in Madhya Pradesh, where 424 copper objects weighing over 200 kg were discovered, along with 102 silver items.

Dating Challenges

- Most copper hoard discoveries were accidental and lacked stratified context, making dating difficult.

- Some hoards, particularly those from Bihar and West Bengal, may belong to the historical period.

Notable Sites

- The site of Saipai in Etawah district is significant because copper objects were found there during excavations in an OCP level, providing a clearer context for dating.

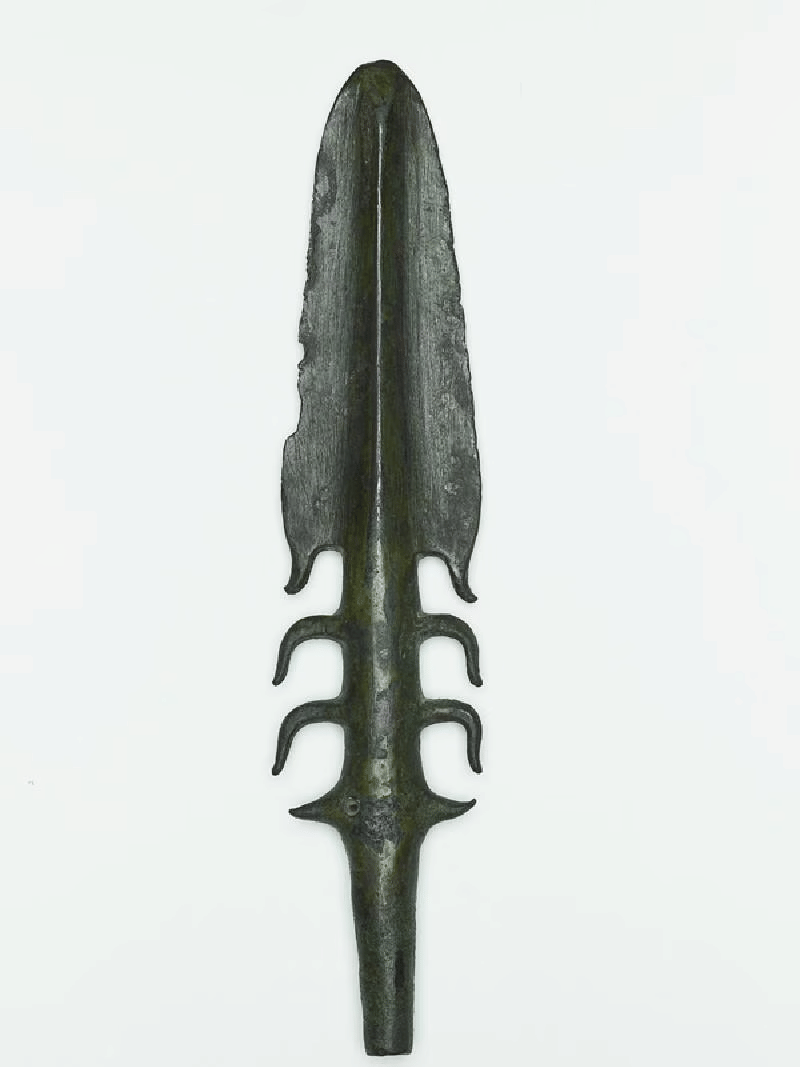

Copper Hoard Objects

The copper hoards comprise various objects, including flat celts, shouldered celts, bar celts, harpoons, antennae swords, and anthropomorphic figures, many of which appear to be part of hunting equipment.

Typological differences among these objects can be linked to geographical regions:

- Eastern Zone (Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa): Predominantly features flat celts, shouldered celts, bar celts, and double axes.

- Uttar Pradesh and Haryana: These types occur alongside anthropomorphs, antennae swords, hooked swords, and harpoons.

- Rajasthan: Mainly yields flat celts and bar celts.

A comparison between Harappan copper artefacts and copper hoard objects reveals significant differences in typology and alloying techniques:

- Copper Hoard Objects: About 46% had up to 7% arsenic alloying.

- Harappan Artefacts: Only 8% showed arsenic alloying.

- Recent findings at the site of Sanauli, including two antennae swords of the copper hoard type in a late Harappan context, suggest the upper Ganga valley emerged as a distinct copper-manufacturing area between the mid-3rd and 2nd millennium BCE.

- This region had interactions extending into Haryana, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, the Deccan, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. It remains unclear whether this was an independent centre of copper working or an extension of the older centre of copper metallurgy in north-eastern Rajasthan.

The Copper Anthropomorph

The copper anthropomorph is a fascinating and mysterious artifact found among the copper hoard objects. Here are some key points about this intriguing item:

- Size and Weight: The anthropomorph measures between 25 to 45 cm in length, 30 to 43 cm in breadth, and can weigh up to 5 kg. Generally, its length is greater than its breadth, with the Bisauli piece being an exception.

- Design Features:The object typically features:

- In-curved arms that are sharpened on the outer edge.

- Plain outstretched legs.

- Head and Arms: The head of the anthropomorph is thicker than the arms due to the way it was crafted, with the top being beaten to create thickness.

Discovery at Madarpur

- In 2001, a remarkable find of 31 copper anthropomorphs was made at Madarpur in the Moradabad district of Uttar Pradesh.

- These figures were discovered by workers while digging soil for mud-brick preparation and were found stacked one on top of the other, indicating they were in situ.

- The large number of anthropomorphic figures found at Madarpur is unprecedented, and the variability in their shapes is intriguing, suggesting they were not mass-produced in identical forms.

- The deposit where these figures were found also contained Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP), indicating a specific cultural context.

- Madarpur appears to have been a specialized site for the production of copper anthropomorphs.

Possible Uses of the Anthropomorph

- Weapon Theory: One suggestion is that the anthropomorph was used as a weapon, possibly thrown to create a whirling effect, similar to a boomerang, to kill birds. However, this theory raises questions about why such elaborate artifacts would be made for this purpose, especially given the variations in shape.

- Ritualistic or Religious Function: Another possibility is that the anthropomorphs had a religious or ritualistic function. In some parts of northern India, tiny anthropomorphic figures similar to those in the copper hoard are worshipped as the god Shani, suggesting a potential spiritual significance.

The Black and Red Ware phase in the doab

- Black and Red Ware (BRW) refers to pottery that features both black and red colors. These colors can appear on the same surface of the pot, or one surface may be black while the other is red. It is important not to confuse BRW with black-on-red ware, such as typical Harappan pottery, where both the inner and outer surfaces of the pot are red, and designs are painted in black.

- Many BRW pots are black on the inside and red on the outside. This effect could be due to the inverted firing technique, where pots are placed upside down in the kiln with vegetal material inside. During firing, the outer part of the pot is exposed to oxidizing conditions, turning red, while the inner part undergoes reducing conditions, turning black. Another possibility is double firing, where pots are first fired red and then re-fired, resulting in one surface becoming black or vice versa.

- Black-and-red pottery is found in various parts of the subcontinent across different cultural contexts. For instance, it appears at neolithic sites like Chirand and Piklihal, pre-Harappan Lothal, Harappan sites in Gujarat such as Lothal, Surkotada, Rojdi, Rangpur, and Desalpur, chalcolithic sites in the middle and lower Ganga valley like Chirand and Pandu Rajar Dhibi, sites of the Ahar/Banas culture, Malwa culture, Kayatha culture, and Jorwe culture, iron age PGW sites, South Indian megalithic sites like Brahmagiri and Nagarjunakonda, and at early historical levels.

Black and Red Ware phase in the doab

- Black and Red Ware (BRW) was initially found at various archaeological sites in different cultural contexts.

- The recognition of a distinct BRW phase in the doab region began during excavations at Atranjikhera in the 1960s.

- At Atranjikhera, BRW levels were discovered between levels of Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP) and Painted Grey Ware (PGW).

- Similar stratigraphic sequences were later observed at other sites like Noh and Jodhpura in Rajasthan.

- There is debate among archaeologists about the connections between BRW in the doab and Rajasthan.

- Excavations at Atranjikhera did not uncover stone or metal artifacts in BRW levels, but found fragments of stone, waste flakes, and cores of various materials such as quartz, chalcedony, agate, and carnelian.

- Other finds included beads made of carnelian, shell, and copper, as well as a bone comb fragment.

- BRW levels at Noh produced items like a shapeless piece of iron, terracotta bead, and bone spike.

- Evidence from OCP levels at Atranjikhera, such as rice, barley, gram, and khesari, suggests that these crops were likely cultivated during the BRW phase as well.

- Grains of rice and moong were found at BRW levels in Atranjikhera, further indicating agricultural practices.

Western India

Ganeshwar and Jodhpura

- Ganeshwar: Period III, starting around 2000 BCE, saw a wide range of pottery and a significant number of copper artifacts, indicating its status as a major center for copper production. There was a decline in microliths and animal bones, suggesting a decrease in hunting activities.

- Jodhpura: Continued to be an important site for early copper metallurgy.

Ahar/Banas Culture

- Ahar: Period I is divided into three sub-periods: Ia (2500 BCE), Ib (2100 BCE), and Ic (1900 BCE).

- Period Ia: Characterized by convex-sided Black and Red Ware (BRW) bowls and associated wares like buff and imitation buff-slipped wares, red wares, and some grey ware.

- Period Ib: BRW continues, with an increase in grey and red wares, but a decline in buff and buff-slipped wares.

- Period Ic: Marked by deeply carinated BRW bowls and lustrous red ware.

Continuity and Change

- Throughout the periods at Ahar, there is a continuity in BRW, but changes in the types and proportions of associated wares reflect evolving cultural practices.

- During Period Ib at Ahar, various artefacts were uncovered, including: 1. Microlithic Tools and Cores: Fluted cores and a blunt-backed blade made of quartz. 2. Beads: Made from materials such as agate, calcite, carnelian, faience, jasper, schist, shell, steatite, bone, and terracotta. 3. Terracotta Objects: Items like ear studs, skin rubbers, head scratchers (?), votive tanks, crucibles, dice, bangles, finials, pipes, pendants, and figurines of humans and animals (including a bull, horse, and possibly an elephant). 4. Copper Items: Including rings, bangles, kohl sticks, celts, and a knife blade. 5. In Period Ic: Tools like microlithic scrapers and borers, beads of carnelian, crystal, glass, jasper, lapis, schist, shell, and terracotta, as well as terracotta skin rubbers, ear studs, and various figurines and decorative items. Copper items included rings and kohl sticks.

- Evidence from Ahar suggests that the inhabitants cultivated rice and possibly millet. The presence of structures and pottery indicates a higher population density in Period Ib compared to other periods. There may have been interactions between the chalcolithic agricultural communities of Ahar and the mesolithic hunter-gatherers at sites like Bagor.

- Investigations at the late Ahar culture site in Purani Marmi (Chittorgarh district, Rajasthan) provided insights into the subsistence practices of the people. Analysis of 545 animal bones from four habitation layers revealed the presence of cattle, sheep, goats, buffalo, blackbuck, spotted deer, and domestic fowl, indicating a pastoral lifestyle with a focus on cattle and buffalo rearing, supplemented by sheep and goat herding and limited hunting. Freshwater molluscs were also found, further informing the subsistence base.

- Additionally, megalithic sites such as Khera, Satmas, and Daosa in the Aravalli region of Rajasthan were noted, though details and dates are scarce. The most common megalith type in this area is the cairn.

- In Gujarat, the transition from the mature Harappan phase to the late Harappan phase saw a significant increase in settlements, particularly in Kutch and Saurashtra. The late Harappan settlements in Gujarat are categorized into two phases: the pre-lustrous red ware sites (such as Lothal B, Rojdi, Babar Kot, and Padri) and the lustrous red ware sites.

- Lothal, during Period B (Phase V), revealed evidence of mud and reed houses, a shift in tool materials from long chert blades to shorter blades of jasper and chalcedony, and changes in bead and weight materials. The use of copper declined, but rectangular steatite seals with Harappan script persisted, albeit without animal motifs. Sites like Rojdi Ia, Rangpur IIB, and IIC also exemplify the late Harappan phase.

Rojdi

- The Rojdi settlement covered approximately 7 hectares.

- It was protected by a stone rubble wall on three sides, with the Bhadar river to the east.

- A double-bastioned gateway was located in the western wall.

- Various metal artifacts were discovered, including an axe, bar celt, bangles, rings, a fishhook, pieces of wire, and a pin.

- Plant remains found at the site included millets, barley, mustard, lentils, linseed, peas, vetches/beans, various kinds of gram, jujube, and several weeds, medicinal plants, and grasses, likely used for animal fodder.

Babar Kot

- The late Harappan site of Babar Kot spanned about 2.7 hectares and featured a stone fortification wall.

- Plant remains at Babar Kot included millets and gram.

Prabhas Patan II (Somnath Patan)

- Prabhas Patan II, located on the banks of the river Hiran, is divided into two sub-phases.

- The earlier sub-phase includes late Harappan pottery without lustrous red ware.

- The later sub-phase features late Harappan pottery associated with lustrous red ware.

- A structural complex interpreted as a warehouse was discovered, made of stone blocks set in mud mortar and divided into smaller compartments.

- Artefacts found at the site included a steatite seal amulet, segmented beads made of faience, cubical chert blades, copper objects, and beads made of chalcedony, carnelian, agate, and a gold ear ornament.

Dwarka

- At Dwarka in Jamnagar district, Gujarat, marine archaeologists discovered the remains of a submerged settlement, including its inner and outer walls, bastions, and a large stone jetty.

- Stone anchors and lustrous red ware were also found at the site.

- The island of Bet Dwarka revealed another submerged site, initially measuring 4 × 0.5 km, with remains of fortifications.

- Artifacts found included a Harappan seal carved with a three-headed animal, lustrous red ware, black and red ware, and a jar inscribed with Harappan writing.

- Additional discoveries comprised a coppersmith’s stone mould and shell bangles.

- A thermoluminescence date of 1570 BCE from Bet Dwarka suggests it as a late Harappan site.

Rupen Valley, North Gujarat

- Numerous late Harappan sites are present in the Rupen valley of north Gujarat, both with and without lustrous red ware.

- These settlements are typically situated on old sand dunes near water sources.

- Most sites are small with thin occupational deposits, indicating they likely served as seasonal camp sites for pastoralists.

At the Kanewal site in Kheda district, located at the mouth of the Gulf of Cambay, archaeologists discovered circular wattle-and-daub huts with rammed floors. The artefacts found at this site included:

- Beads made of carnelian, faience, shell, and terracotta

- Terracotta spindle whorls and net sinkers

- Copper objects

- Various types of pottery including lustrous red ware

- Terracotta cakes

Literacy Evidence

- Some pottery found in this area had graffiti in the Harappan script, suggesting that the people living here had some level of literacy.

The Middle Ganga Valley

- Protohistoric Sites There are numerous protohistoric sites in the Middle Ganga Valley, particularly in the trans-Sarayu region. One such site is Narhan, located in Gorakhpur district, Uttar Pradesh, on the northern bank of the Sarayu River (Ghaghara), about 30 km east of Imlidih. Excavations at Narhan revealed a cultural sequence spanning from the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE to the 7th century CE.

Narhan Culture

- Remains of wattle-and-daub houses with post-holes and hearths were discovered, along with pottery marked by white-painted black-red ware (BRW), white-painted black-slipped ware, red-slipped ware, and plain red ware.

- Period I at Narhan, known as the Narhan culture, was dated to around 1300–700 BCE.

Artefacts Found

- Copper objects such as a ring and fishhook were also found, made of low-tin bronze using techniques like alloying, cold working, annealing, and casting.

- Other artefacts included bone points, pottery discs, terracotta beads, dabbers, and balls, as well as a polished stone axe.

Metalworking Skills

- The metal workers at Narhan were skilled in various techniques, and the copper ores used likely came from the Rakha mines in Bihar.

Plant and Animal Remains

- An extensive range of plant remains was found at Narhan, including cultivated rice, hulled and six-row barley, three kinds of wheat, pea, green gram, gram or chickpea, khesari, and oilseeds like mustard and flax.

- Fragments of various trees and plants such as mahua, sal, tamarind, teak, siris, babul, mulberry, and others were identified.

- Animal bone remains included those of humped cattle, sheep/goat, wild deer or antelope, horse, and fish.

Fishhook and Thread Impression

- An interesting find at Narhan was the impression of a fishhook and thread on a mud clod.

- Analysis showed that the hook was made of iron and the thread from ramie, a type of fibre.

Period I

- Khairadih: Early occupation featured Black Red Ware (BRW) and associated pottery, with calibrated dates ranging from 1395 to 848 BCE.

- Rajghat: Initial occupation characterized by black-slipped ware.

- Raja Karna Ka Tila: Period I yielded BRW, microlith chips, clay sling balls, shells, terracotta beads and discs, and bone points and arrowheads. Identified crops include rice, barley, ragi, foxtail millet, lentils, field peas, khesari, and moong.

- Imlidih Khurd (Period I): Pre-Narhan culture dating back to around 1300 BCE. Artifacts included cord-or-mat-impressed red ware, wattle-and-daub house remains, storage pits, circular structures, ovens, and various beads and pottery. Faunal remains comprised domesticated animals (cattle, sheep/goat, pig) and aquatic species. Plant remains included rice, barley, wheat, millets, legumes, and fruits. Evidence of established agriculture with two annual crop cycles in the trans-Sarayu plain during the early 2nd millennium BCE.

Period II

- Raja Karna Ka Tila: Introduction of iron artifacts.

- Imlidih Khurd (Period II): Narhan culture (c. 1300–800 BCE) marked by structural activities, including mud floors, post-holes, and ovens. Typical pottery included white-painted BRW.

- Artifacts comprised bone points, pottery discs, terracotta beads, and copper items. Plant remains included various grains, legumes, and wild fruits. Faunal remains included domesticated animals (cattle, goats/sheep, horse, dog) and wild species (boar, deer). Aquatic fauna from Period I persisted.

Agiabir Excavations

- Location: Agiabir site in the Mirzapur district, covering 40 hectares.

- Period I (Narhan Culture Phase): Pottery types included Black Red Ware (BRW), black-slipped ware, and red ware, with some variations from typical Narhan ware.

- Living Conditions: People resided in wattle-and-daub huts.

- Storage: Two grain storage silos were discovered.

- Bead Production: A workshop for making beads, particularly agate beads, was identified.

- Artifacts Found: Faience objects, microliths, terracotta beads, bone points, terracotta discs, a copper fishhook, and a clay lamp or incense burner.

- Food Habits: Evidence of food habits was obtained from fireplaces with charred animal bones.

- Period II (Pre-NBP with Iron): Characterized by notable finds of iron and copper objects.

Megalithic Sites in Northern Vindhyas

- Overview: Sites in Allahabad, Banda, Varanasi, and Mirzapur districts with megaliths such as cairns and stone circles.

- Burial Practices: Some graves showed fractional burial, while others involved animal burials.

- Kotia Findings: Graves with few human remains but animal remains (sheep, pig, cattle) with cut marks indicating they were killed at burial.

- Memorials: Some megaliths without skeletal remains likely served as memorials.

Megalithic Site of Kakoria

- Location: North-west of the megalithic cemetery, along the Chandraprabha river.

- Pottery: Included BRW, black-slipped ware, and red ware, mostly wheel-made, with forms like dishes, bowls, and jars.

- Artifacts: Microliths made of agate, chalcedony, and chert, terracotta and semi-precious stone beads, sling balls, and grinding stones.

Kotia Findings

- Location: Belan valley, southern Uttar Pradesh.

- Pottery: Included BRW, red ware, black-slipped ware, and coarse black or grey ware.

- Animal Remains: Bone fragments of domesticated animals like ox, sheep, and pig, some with cut marks.

- Metallurgy: Evidence of advanced ironworking with tools like a spearhead, sickles, arrowhead, and adze.

North-Eastern India

Pre-Iron to Early Iron Age Sites

- Kakoria: Suggested date ranging from the 2nd millennium BCE (or earlier) to the 7th century CE.

- Jang Mahal: Estimated to belong to the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE.

- Kotia: Placed between approximately 800 BCE and 300 BCE.

Early Phase of Occupation:

- Chirand: Occupation continued into the 2nd millennium BCE. Chalcolithic Period II shows continuity with Neolithic Period I.

- Period II Findings: Microliths, polished celts, terracotta and steatite beads, semiprecious stone beads. Pottery included Black and Red Ware (BRW), grey/buff, black- and red-slipped wares. Copper appeared, with evidence of iron objects in upper levels. Earliest calibrated dates: 1936–1683 BCE.

Neolithic-Chalcolithic Continuity:

- Senuar: Period II is Neolithic-Chalcolithic. 2.02 m thick deposit shows continuity with preceding period. New elements: copper objects (fishhook, wire, needle), fragmentary lead rod. Introduction of bread wheat, kondon millet, chickpea, green pea, horse gram. Increased faunal remains compared to earlier period.

Barudih Sites: Cultural Connections and Artefacts

- Barudih Findings: Microliths, Neolithic celts, iron slag, wheel-made pottery in the same ‘Neolithic’ level. Iron objects included a sickle. Earliest radiocarbon dates: 1401–837 BCE.

- Cultural Patterns: Close connections between cultural patterns in Bihar and West Bengal. Over 65 BRW sites identified in West Bengal.

- Settlement Categories: Settlements in West Bengal BRW sites divided into three categories based on size: 0.5–2 acres, 4–5 acres, and 8–9 acres.

- Chronological Issue: BRW phase in West Bengal began around the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE. Black and Red Ware settlements found up to about 400 BCE, indicating different periods needing chronological identification.

Artefact Similarity:

- Bengal BRW Sites: Similar range of artefacts including pottery, stone tools, semi-precious stone beads, and limited copper objects. Rice likely the most important crop. Abundance of deer bones and antlers suggests large tracts of forests and grassy land.

- Interaction with Chotanagpur Plateau: Agriculturists of the plains interacting with communities in the Chotanagpur plateau, rich in stone and metal (copper and tin).

- Iron Industry Emergence: Familiarity with iron in some BRW sites, but significant emergence of the iron industry in the area towards the end of the BRW phase.

West Bengal

- Pandu Rajar Dhibi: An important site in the Ajay valley.

- Period I (c. 1500 BCE onwards): Found microliths, ground stone tools, bone tools, and pottery. No metal was discovered, possibly due to limited excavation area.

- Chalcolithic Period II: Discovered copper artefacts, semi-precious stone beads, terracotta figurines, iron spearheads, slag, and ovens. Pottery included painted BRW and other wares. Faunal remains included domesticated and wild animals, fish, turtles, and fowl.

Bharatpur, Damodar Valley

- Period I (1735–1417 BCE): Found microliths, Neolithic celts, bone tools, steatite beads, copper objects, and pottery mainly of BRW.

Mahisdal, Kopai Valley

- Period I (1619–1415 BCE): Evidence of house floors with terracotta nodules, microliths, bone tools, steatite and semi-precious stone beads, terracotta bangles, phallus, and a copper celt. Pottery included BRW and associated wares. A storage pit with charred rice grains was also found.

Orissa

- Neolithic stone tools found as surface finds in various locations, but stratified finds and dates are lacking. Sites include Kuchai (domesticated rice at Baidipur), Sankarganj (calibrated date of c. 800 BCE), and Sulabhdihi (neolithic celt manufacturing site).

Golbai Sasan, Mandakini River, Orissa

- Neolithic Period I: Evidence of floors and post-holes, red and grey handmade pottery with cord or tortoiseshell impressions, and worked bone.

- Neolithic Period IIA (Chalcolithic): Outlines of circular huts (3.9–7.9 m in diameter) with hearths and post holes. Both handmade and wheel-made pottery found, including BRW, dull red ware, and various burnished wares. Copper artefacts were also discovered.

Archaeological Findings in the North-Eastern States

- The North-Eastern states of India, including Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Tripura, Manipur, Nagaland, and Mizoram, are rich in archaeological potential but have not been explored thoroughly.

- Limited excavations have revealed neolithic tools, primarily found on the surface in areas like the Garo, Cachar, and Naga hills. Despite the scarcity of dates and excavated sites, the available evidence is crucial for understanding the region's past.

Sarutaru and Surrounding Areas

- Excavations at Sarutaru, located 25 km south-east of Guwahati, uncovered neolithic artefacts such as shouldered celts and round-butted axes, along with handmade pottery in brown, buff, and grey wares, some featuring cord impressions.

- However, the neolithic phase at Sarutaru might date to the early centuries CE, suggesting a more recent timeline for these findings.

- Nearby excavations at Marakdola revealed a 1-meter thick deposit containing wheel-made pottery of fine kaolin clay, similar to pottery found at Ambari near Guwahati, dated between the 7th and 12th centuries CE.

North Garo Hills

- At Daojali Hading in the north Garo hills, a 45 cm thick neolithic deposit yielded a variety of tools, including stone and fossil wood axes, adzes, chisels, hoes, grinding slabs, querns, and mullers.

- Pottery findings included handmade grey and dull-red pottery with cord marks, dull-red stamped pottery, and plain red pottery, indicating a diverse range of neolithic activities in the area.

- Excavations at Selbalgiri revealed a microlithic level followed by a 60 cm deposit containing stone celts and pottery, further contributing to the understanding of neolithic practices in the region.

Nagaland and Manipur

- Neolithic tools and handmade grey ware have been discovered at various locations in Nagaland, although these sites have not undergone extensive excavation.

- The site of Napchik in Manipur has provided an early thermoluminescence date of 1650 ± 350 BCE for handmade cordmarked ware, along with artefacts such as stone choppers, scrapers, flakes, edged knives, grinding stones, and polished celts, indicating a rich neolithic presence.

Meghalaya

- Neolithic tools have been found at multiple sites in Meghalaya, with a small-scale excavation at Selbalgiri and a more significant excavation at Pynthorlangthen revealing a 1-meter thick neolithic deposit.

- The Pynthorlangthen site, in particular, appeared to function as a factory site, producing neolithic adzes, axes, chisels, points, blades, and scrapers, contributing to the understanding of tool production and use in the region during the neolithic period.

- Not all sites in the North-east that have produced stone tools and handmade pottery are necessarily ancient; some are definitively more recent. For instance, the 'neolithic' level at the Kanai Gaon Reserve in Dibrugarh district has been dated to the 6th century CE. More excavations and a clearer understanding of the chronology of these sites are needed to get a better picture of the neolithic and neolithic–chalcolithic periods in this part of the subcontinent.

- There have been observations of similarities between some artefact types from this region and those from East and South-east Asia, but no concrete conclusions can be drawn about the connections or interactions at this time.

Cultural Sequence in Central India

The Ahar Culture

- The Ahar culture, known for its distinctive pottery and artefacts, spread from southeastern Rajasthan to the Malwa region of central India.

- Ahar culture levels have been identified at various sites, including Kayatha and several locations in the Chambal valley.

- Typical Pottery:

- Coarse, wheel-made Black and Red Ware with white designs, often painted on the outer surface.

- Red-slipped ware variants, including tan, orange, chocolate, and brown-slipped pottery, all highly burnished.

- Coarse handmade red and grey wares.

- Other Artefacts:

- Necklaces made of short, cylindrical beads.

- A significant blade tool industry at Ahar levels, particularly at Kayatha.

- Terracotta Figurines:

- Naturalistic or stylized bull figurines made of fine clay, baked at a high temperature with few impurities.

- Figurines often feature prominent humps and long, pointed horns, with no surface decoration, only nail marks.

- Notable finds include a pair of short horns on a pedestal, possibly with cultic significance.

The Malwa Culture

After the Ahar culture phase, the Malwa culture emerged, with Navdatoli, located in the west Nimar district along the southern banks of the Narmada River, being the largest settlement of this culture. The settlement at Navdatoli is dated to between 2000 and 1750 BCE. Other notable sites of the Malwa culture include Maheshwar, Nagda, and Eran. The recently excavated site of Chichali in Madhya Pradesh shows a cultural sequence that includes Ahar, Malwa, Jorwe, and early historical levels.

- Typical Malwa pottery features a coarse core with a thick buff or orange slip. Designs were painted in black or dark brown, usually on the upper part of the pots. The pottery includes various forms such as lotas, concave-sided bowls, channel-spouted bowls, and pedestalled goblets. Malwa ware is known for its rich variety of forms and designs, with over 600 different motifs, including geometric patterns and naturalistic representations of plants, animals, and humans. Some of the animals depicted include blackbuck, bull, deer, peacock, pig, tiger, panther, fox, tortoise, crocodile, and insects.

- At Navdatoli, there is no evidence of planned construction; houses were built randomly with lanes in between. People lived in circular or oblong wattle-and-daub houses with lime-plastered floors. Wooden posts supported a conical roof, and the walls were low, sometimes nonexistent, with the roof sloping down to ground level. The circular houses ranged from 1 to 4.5 meters in diameter, while rectangular houses measured 5 to 6 meters in length. Chulhas (cooking hearths) and storage jars were commonly found in these houses. At Nagda, evidence of mud-brick construction was discovered, while Eran featured a massive mud fortification wall and a moat.

- Artefacts from Malwa culture sites indicate a greater abundance of stone tools compared to copper items, likely due to the scarcity of copper. Stone blades were common, and over 23,000 microliths made of chalcedony, carnelian, agate, jasper, and quartz were found at Navdatoli. This suggests that households at the site made their own tools, with some being hafted and others handheld. Stone artefacts included saddle querns, rubbers, hammer stones, and mace heads or weights.

- Copper artefacts comprised flat axes, wire rings, beads, bangles, fishhooks, chisels, nail parers, thick pins, and a broken mid-ribbed sword, with some items showing tin and lead alloying. Navdatoli also yielded beads made of various materials, including steatite, terracotta, faience, agate, amazonite, carnelian, chalcedony, glass, jasper, lapis lazuli, and shell, as well as terracotta animal figurines and spindle whorls. Plant remains found at the site included wheat, barley, linseed, black gram, moong, lentil, anwala, ber, khesari, and later, rice. Faunal remains included bones of wild deer and domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs.

- Excavations at sites belonging to the Malwa culture have uncovered evidence of religious or ritualistic practices. At Navdatoli, for instance, researchers discovered a pit measuring 2.3 × 1.92 × 1.35 meters dug into the floor of a house from the earliest phase of occupation. The pit's sides and base were plastered with mud, and it contained wood, along with charred wooden posts at its four corners. This pit is believed to have functioned as a fire altarfor conducting sacrifices.

- Another notable find at Navdatoli was a large storage jar adorned with intricate designs. On one side of the jar, there was an image of a female figure(possibly a goddess or a worshipper) alongside a depiction of a lizard or alligator and what appears to be a shrine. The jar featured four such shrines, with decorative patterns on its shoulder. On the opposite side of the jar, there was a shrine with a tortoise, further emphasizing the religious significance of the vessel. Additionally, a shell amulet shaped like a tortoise was discovered at Malwa culture levels in Prakash, Maharashtra, linking these cultural practices.

Figurines and Rituals

- Bull Figurines: Bull figurines have been found at various Malwa culture sites, indicating their significance in the culture. Evidence from Dangwada points to the worship of bulls, trees, snakes, and female deities. There are also fire altars at these sites, suggesting that sacrifices were likely performed there.

- Burials: Malwa culture sites provide evidence of burials within houses. For instance, at Azadpur near Indore, a child burial was discovered under the floor of a house. The body was positioned with a northwest orientation, and the feet had been removed post-mortem. Grave goods included a serrated blade, a small terracotta tablet placed under the head, and a stone positioned to the right of the head.

Late Harappan Influence and Cultural Sequence

- The discoveries at Daimabad indicate that the late Harappan culture extended into the Deccan region. The typical chalcolithic cultural sequence in this area includes the Savalda culture, followed by the Malwa and Jorwe cultures.

- The Savalda culture has been previously discussed in Chapter 3. Here, the focus is on the late Harappan phase, with particular emphasis on the Malwa and Jorwe cultures, especially at the sites of Daimabad and Inamgaon.

Insights from Excavations

- Detailed excavation reports from Daimabad and Inamgaon offer a wealth of information about the early chalcolithic farmers in the Deccan.

- These reports provide insights into various aspects of their lives, including their agricultural practices, settlement patterns, and cultural activities. The findings from these sites contribute to a better understanding of the transition and development of chalcolithic cultures in the Deccan region.

Malwa Culture in the Deccan

- The Malwa culture originated in central India and later spread to the Deccan region.

- In the Deccan, the primary sites were located in the Tapi valley, with fewer settlements in the Pravara–Godavari and Bhima valleys.

- The Malwa pottery found in the Deccan differs from that in central India. In the Deccan:

- The pottery fabric is finer, not gritty, and is evenly baked.

- Pots were uniformly fired at high temperatures.

- Typical pottery forms include deep bowls and spouted vessels with flaring mouths, which are not found in central India.

- Coarse handmade red or grey ware, similar to that of the southern Neolithic, was also used.

- Notable Malwa culture sites in the Deccan includeDaimabad, Inamgaon, and Prakash.

Daimabad Site

- Location: Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra, on the banks of the Pravara River, a tributary of the Godavari.

- Excavation: Conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India from 1976 to 1979, led by S. A. Sali.

- Significance: Daimabad has a well-documented sequence of chalcolithic periods.

Periods at Daimabad

- Period I (before 2300/2200 BCE) : Savalda culture.

- Period II (2300/2200–1800 BCE) : Late Harappan.

- Period III (1800–1600 BCE) : Daimabad culture.

- Period IV (1600–1400 BCE) : Malwa culture.

- Period V (1400–1000 BCE) : Jorwe culture.

Findings from Daimabad

- Period II (late Harappan) : Settlement size increased to about 20 hectares.

- Houses were organized along a wall made of black clay, 30–50 cm thick.

- Notable discoveries :

- Grave with a skeleton covered with reeds or fibrous plants.

- Pottery: Fine red ware with black designs, burnished grey ware, coarse handmade ware, ribbed bichrome and deep red wares.

- Seals with Harappan writing and inscribed potsherds.

- Other artefacts: Stone tools, beads, bangles, gold beads, terracotta measuring scale, and evidence of local copper smelting.

- Plant remains: Millets, gram, moong, and first appearance of horse gram.

Pottery from Various Phases at Daimabad

- Period III: This period, known as the 'Daimabad culture,' followed a break in occupation of about fifty years between Periods II and III. The typical pottery of this period was black-on-buff/cream ware. Other artifacts from this period included: microlithic blades, bone tools, beads, and a single piece of worked elephant tusk. A part of a copper-smelting furnace was also found, along with three different types of burials: a pit burial, post-cremation urn burial, and symbolic burial. The plant remains from this period included a new addition: hyacinth bean.

- Period IV: This period belonged to the Malwa culture and revealed many structural remains. People lived in relatively spacious, usually rectangular mud houses with mud-plastered floors, wooden posts embedded in thick mud walls, and steps leading up to the doorway from outside. A specific house with two furnaces, one containing a copper razor, was identified as a coppersmith's workshop. Some structures were tentatively identified as religious based on the occurrence of fire altars.

- An elaborate structural complex was discovered, including a mud platform with fire altars of different shapes and an apsidal temple associated with sacrificial activities. There were 16 burials, either pit or urn burials, with twigs of a fibrous plant laid out at the bottom of the pits. Artifacts from Period IV included microlithic blades, copper objects, faience beads, and terracotta and bone objects. Plant remains included barley, three kinds of wheat, ragi, lentils, pulses, and ber. It is possible that Sugandha bela (Pavonia odorata) was used to make a perfume.

The Daimabad Bronzes

- In 1974, a farmer named Chhabu Laxman Bhil discovered a hoard of metal objects while digging at the base of a shrub in Daimabad village. The headman of a nearby village reported the discovery to the police, and the objects were later acquired by the Archaeological Survey of India from district authorities. The hoard consisted of four objects, including a detailed figure of a man standing on a two-wheeled chariot driven by two yoked oxen. The man is depicted holding the guard with one hand and a curved stick with the other, with specific features like an elongated chest and belly, a protruding chin and lip, and a bun hairstyle.

- The objects were solidly cast and heavy, weighing a total of 60 kg. They demonstrate significant skill in casting and aesthetic craftsmanship. Chemical analysis revealed that they were made of bronze with varying but low tin content.

- Inamgaon (in Pune district) is situated on a terrace of the Ghod River, a tributary of the Bhima River. It is one of the largest and most thoroughly excavated Chalcolithic sites in Maharashtra. The excavations were carried out by a team from Deccan College, Pune, led by M. K. Dhavalikar, H. D. Sankalia, and Z. D. Ansari, over 12 seasons between 1968 and 1983, providing valuable insights into the lives of ancient farmers in the region.

- Period I (c. 1600–1400 BCE) at Inamgaon is associated with the Malwa culture. During this period, 134 houses were excavated, with 32 belonging to Period I. Of these, 28 were rectangular, 1 circular, and 3 were pit dwellings. The rectangular houses had rounded corners and low mud walls, topped with a wattle-and-daub construction and a thatched, conical roof, resembling modern village houses in the area.

- These houses were spacious, averaging 8 × 5 meters, often divided by a wattle-and-daub screen. Inside, oval-shaped hearths for cooking were common, with additional hearths in courtyards for meat roasting. Two types of storage structures were found: overground bins made of wickerwork and silos dug into the ground, located inside or outside the houses.

Inamgaon: Period I (Malwa Phase) Pot

During the early Chalcolithic period, farmers in the Deccan region obtained their food through a combination of farming, hunting, and fishing. Barley was the primary crop, which is not surprising given that this area does not receive enough rainfall for wheat cultivation.

- The faunal remains found at Inamgaon included bones of domesticated animals such as humped cattle, buffalo, goat, sheep, dog, and pig. Wild animal bones included those of sambar, chital, blackbuck, hare, and mongoose, as well as birds, reptiles, fish, and mollusks.

- Tools made of stone and copper have been discovered at various sites associated with the Malwa culture. The most commonly used stone materials were siliceous stones such as chalcedony and agate, and the tools were typically made from blades or flakes. Polished stone axes are rare. Microwear analysis has identified tools used for various purposes, including plant working, meat cutting, antler or bone working, and hide scraping. Copper artifacts included knives, chisels, fishhooks, axes, and ornaments such as bangles and beads.

- At Inamgaon, there were many beads and pendants made from terracotta, jasper, ivory, and carnelian, as well as materials such as shell, steatite, faience, paste, amazonite, serpentine, copper, gold, and calcite. Among the semi-precious stones, locally available jasper and carnelian were used more frequently than those obtained from distant sources. The presence of shell beads at Inamgaon is notable, as this inland site is located about 200 km from the sea.

- In Period I at Inamgaon, the only burials found were child burials. In all three periods, children were buried in pits in two urns placed mouth to mouth horizontally. Terracotta figurines of humans and animals were found at all levels, and some female figurines may have had cultic significance. The large number of bull figurines suggests that this animal may have been venerated.

The Jorwe culture of the Deccan

- The Jorwe culture was initially identified at the site of Jorwe and was later found to extend over a vast area, encompassing almost all of modern Maharashtra, except for the coastal Konkan district. The Pravara–Godavari valleys are believed to be the core area of this culture, while the peripheral zone extended north to the Tapi river and south to the Krishna river.

- Major excavated sites of the Jorwe culture include Daimabad, Inamgaon, Theur, Songaon, Chandoli, Bahal, Prakash, Jorwe, and Nevasa. Among these, Prakash is the largest Jorwe site in the Tapi valley, Daimabad in the Godavari valley, and Inamgaon in the Bhima valley. All three of these settlements were over 20 hectares in size, indicating they were permanent agricultural villages. Jorwe, Bahal, and Nevasa are considered medium-sized settlements, while average Jorwe culture settlements were smaller, typically 1–2 hectares. Sites like Walki and Gotkhil were predominantly seasonal agricultural and pastoral sites, and Garmals appears to have been a temporary camp site near a source of chalcedony. This suggests a hierarchical settlement pattern within the Jorwe culture.

- Radiocarbon dating from sites such as Nevasa, Chandoli, and Songaon indicates a timeframe of around 1300–1000 BCE for the Jorwe culture. At Inamgaon, however, the early Jorwe culture dates to approximately 1400–1000 BCE, while the late Jorwe phase is dated to around 1000–700 BCE.

Early Jorwe Period Terracotta Lamp

- Jorwe pottery is known for its fine quality, being well-baked and rich in various forms and designs.

- The pots typically feature a red or bright-orange matte surface, adorned with geometric designs painted in black.

- Common shapes include:

- Concave-sided bowls with sharp carination

- Spouted jars with flaring mouths

- High-necked jars with globular profiles

- Coarse, handmade red and grey pottery is also present, along with oval lamps of red and grey ware.

- A pottery kiln has been discovered at Inamgaon, indicating advanced pottery-making techniques in the region.

Pottery from Different Periods, Prakash

Daimabad : Period V and the Jorwe Culture

- Settlement expanded to approximately 30 hectares.

- Evidence of a mud fortification wall with bastions.

- Houses identified for various occupations: butcher, lime maker, potter, bead maker, and merchant.

- Discovery of an elliptical structure with approach paths plastered with cow dung.

- Offerings found in pots included copper objects, shaped stones, and tool hafts made of cattle bones.

- Artefacts included microliths, copper objects, beads, and terracotta figurines.

- Terracotta cylinder seal depicting a horse-drawn cart or chariot.

- Crop List : Similar to the preceding period with the addition of new millets: kodon millet, foxtail millet, and jowar.

- Burials : Out of 48, 44 were urn burials, three were extended pit burials, and one was an extended burial in an urn.

- Most burials were of infants and young people, except for one late Harappan burial.

- Dental analysis showed dental caries, gross enamel hypoplasia, tartar accumulation, and calculus deposits.

- One case of infantile scurvy noted.

Inamgaon : Periods II (Early Jorwe) and III (Late Jorwe)

- Discovery of rectangular houses similar to those in Period I (Malwa culture).

- Houses laid out in rows with an open space in between, indicating planning.

- Fire pits found in houses, used for cooking with vessels placed on flat stones.

- Animal Tethering : Nitrogen levels in soil indicate animals were tied in courtyards.

- Settlement Layout : Western Periphery : Houses of artisans (potters, goldsmiths, lime makers, bead makers, ivory carvers). Central Area : Homes of farmers and well-to-do individuals, including a large five-roomed structure identified as the ruling chief's house with a granary nearby. Period III : Chief’s residence moved to the eastern part of the settlement, near the river.

- Public Structures : Possible granary or fire-worship temple identified. Community efforts evident in the construction of a stone embankment wall for flood protection and water storage, along with irrigation channels.

- Social and Political Organization : Inferred from material evidence, suggesting a ranked society based on settlement layout and burial practices.

- Inamgaon’s subsistence base comprised farming, hunting, and fishing. Remains of grains and seeds such as barley, wheat, lentil, kulthi, grass pea, ber, and a few grains of rice were discovered, with barley being the primary crop, followed by wheat. Domesticated animals included cattle, buffalo, goat, sheep, pig, and horse, with cattle being the most important throughout. Hunting included animals like deer, and the presence of fishhooks indicated fishing activities.

- Period II was the most prosperous time at Inamgaon, showing increased farming and animal domestication, possibly with irrigation for winter crops like wheat, peas, and lentils. However, in Period III, there was a decline in productivity, with a shift to hardier crops and increased reliance on hunting and gathering wild plants.

- A variety of artifacts from Jorwe culture were found, including blade flakes, polished stone axes, and chisels, with occasional gold ornaments. Pottery and lime kilns were identified at Inamgaon, and copper was used sparingly for various items, with a furnace for copper extraction discovered at the site.

Food, Nutrition, and Health in Inamgaon

Scientists analyzed 165 human bone samples from Inamgaon burials to understand the relationship between subsistence, age, status, and dietary changes over time. The findings indicated that:

- During the early Jorwe phase, people consumed a diet with more agriculturally produced plant food, animal food, and dairy food.

- In the late Jorwe phase, the diet shifted to being rich in animal food, fish, and locally gathered plants.

- Burials were typically under house floors, sometimes in courtyards, with bones found in rectangular houses reflecting a more nutritious diet compared to those in round huts, suggesting status differences within the community.

1. Diet and Weaning Age

- There was no noticeable difference in the diet of males and females during any phase of the study.

- The increase in weaning age during the late Jorwe period might be linked to a gradual transition from an agricultural lifestyle to a semi-nomadic one.

2. Health Issues Observed in Skeletons

- Microscopic examination of the skeletons revealed signs of infantile scurvy, various degenerative joint diseases, and fractures.

3. Dental Health

- The dental health of the population was generally good, with a low incidence of dental caries and gross enamel hypoplasia.

- However, individuals appeared to lose their teeth relatively early in life.

Figurines and Household Rituals

- Female figurines made of clay, both baked and unbaked, have been discovered at Inamgaon and Nevasa. Some of these figurines are headless, suggesting they may have represented goddesses associated with fertility.

- An intriguing find at Inamgaon involved the discovery of a female figurine placed inside a clay receptacle beneath a house floor from Period II (early Jorwe phase).

- Over this figurine was a headless female figurine and a bull, all made of unbaked clay, indicating they were intended for temporary use.

- The headless figurine had a hole in its abdomen, and the bull had a hole in its back. When a stick was inserted through both holes, the headless figurine fit perfectly on the bull’s back.

- The burial of these figurines under a house floor suggests their significance in an important household ritual.

- It is possible that the headless figurine represented a goddess linked to fertility, childbirth, or the welfare of children.

Networks of Exchange in Jorwe Culture

- Evidence from Jorwe levels at Inamgaon suggests the existence of exchange networks during the Jorwe culture period.

- Sources of Materials:

- Gold and ivory were likely sourced from Karnataka.

- Conch shell was obtained from the Saurashtra coast.

- Amazonite came from Rajpipla in Gujarat.

- Copper may have been locally sourced or obtained from Rajasthan and the Amreli district in Gujarat.

- Haematite, marine fish, and marine shell were likely sourced from the Konkan coast.

- Hyacinth bean was probably obtained from the upper Ghod valley.

- Exchange Practices:

- The chalcolithic farmers may have exchanged beads and pottery with hunter-gatherers in regions like the Konkan coast.

- Inamgaon and Daimabad within the Jorwe culture zone may have been significant suppliers of pottery to other settlements.

Burial Practices in Jorwe Culture

At Jorwe culture sites, burial practices varied for adults and children:

- Adults were typically buried in an extended position.

- Children were placed in urns, which were positioned horizontally, mouth to mouth.

Location of Burials

- Burial pits were usually dug into the floors of houses, and occasionally in the courtyard.

- An unusual practice involved cutting off the feet of adult corpses, possibly to keep the spirit of the deceased within the house.

Urn Burial at Inamgaon

- At Inamgaon, a notable urn burial was found in the courtyard of a large five-room house.

- This burial dates to around 1000 BCE and represents a transitional phase between Periods II and III.

Details of the Urn

- The urn, made of unbaked clay, stood 80 cm high and 50 cm wide.

- It had four stumpy legs and featured a painting of a boat with long oars.

- One side of the urn was modelled to resemble a woman’s abdomen.

Contents of the Urn

- Inside the urn was the skeleton of a male, approximately 40 years old, seated in a foetal position.

- Unlike other burials, his feet were intact and not cut off.

Nearby Burial

- Close to this urn burial was an earlier burial consisting of a four-legged jar and a similar jar cut in half, placed beside it.

- This burial contained no skeletal remains, only a painted globular jar with a lid.

- This might represent a symbolic burial of a person whose body was not found, possibly someone who died in battle.

Significance of the Burials

- These two burials are believed to belong to important individuals, possibly representing two generations of ruling chiefs.

Neolithic-Chalcolithic Settlements in South India

Third Phase:

- Followed the second phase at various sites.

- Continued use of stone tools, with an increase in copper and bronze tools like chisels and flat axes.

- New pottery elements included grey and buff ware with a harder surface, as well as wheel-made unburnished ware with purple paint.

- Radiocarbon dating for this phase is limited, but it is approximately dated to 1500–1050 BCE.

- Upper levels of most sites transition into a megalithic phase.

Sanganakallu (Bellary District):

- Earlier Neolithic Phase: A-ceramic and lacking copper.

- Neolithic-Chalcolithic Phase: Characterized by copper tools and wheel-made pottery.

- Both phases included ground and polished stone tools, microliths, bone points, and chisels.

- Pottery consisted of black-on-red ware (some with red ochre designs), pale grey, burnished grey, and brown wares, along with coarse brown and black pottery.

- Terracotta figurines mainly depicted bulls and birds.

- Animal bones found included those of cattle, sheep, goats, and dogs.

- Neolithic phase at Sanganakallu likely began around 2000 BCE.

Brahmagiri (Chitradurga Area):

- Neolithic Period IA: Characterized by remains of wattle-and-daub huts with wooden or bamboo posts supported by stone.

- Artefacts included ground and polished stone tools, microlithic blades, and handmade grey pottery.

- Neolithic Period IB: Marked by the appearance of copper and bronze objects.

- Burial practices included extended burials of adults and urn burials of children.

Piklihal:

- Lower Levels: Featured circular hut floors, Neolithic tools, and microlithic blades. Pottery was mostly handmade, consisting of grey and burnished grey wares, with some black, buff, and red/brown wares, some decorated with red ochre and purple paintings. Terracotta figurines of humans, animals, and birds were found, along with bones of domesticated cattle, goats, and sheep.

- Upper Neolithic Levels: Indicated rectangular wattle-and-daub huts, one with an indoor hearth and an outdoor saddle quern. Artefacts included fragments of a copper bowl and pottery made on a slow wheel. New pottery types included painted black-on-red ware and a green ware with a mottled surface. Beads made of carnelian, shell, and magnesite were also discovered.

New Directions in Research

Rock Pictures in Karnataka and Andhra

- Rock pictures on granite can be found in places like Kupgal, Piklihal, and Maski in Karnataka and Andhra.

- These pictures are hard to date precisely, but we can estimate their age based on factors like style, content, and weathering.

- Some images might be from the Mesolithic period, while others could be from the Neolithic-Chalcolithic period, and some are much later.

Methods of Creating Rock Pictures

- Many pictures were made by crayoning, which involves rubbing dry colours onto the stone surface, rather than painting.

- There are also rock bruisings, where motifs were hammered or pecked into the rock surface.

- The most common theme in these pictures is cattle.

Kupgal Rock Art

- Location : Kupgal is in the Bellary district of Karnataka, featuring granite hills known as Hiregudda.

- Rock Pictures : The site has hundreds of rock pictures, mostly bruisings, ranging from the Neolithic period to modern times.

- Common Themes : The most frequent theme is humped cattle with long horns, often depicted with anthropomorphic figures. Other themes include individual human figures, scenes of intercourse, and possible dance scenes.

- Less Frequent Motifs : These include elephants, tigers, deer,buffalo, birds, footprints, and abstract designs.

Interpretation by N. Boivin

- Access and Creation : Some locations for the images were hard to reach, suggesting that the artists and viewers had to make an effort to access them.

- Themes of Prowess and Ritual : The images may celebrate male prowess, sexuality, and the connection between men and cattle, possibly created by young men involved in cattle herding or raiding.

- Stone Quarrying and Tool Production : Kupgal was likely a significant centre for stone quarrying and tool production, and the pictures might have been made by men involved in these activities.

- Ritualized Activity and Sound : The creation and viewing of these pictures could have been part of a ritual involving 'rock music', as some boulders at the site were used for percussion, producing deep sounds like bells or gongs.

- Broader Context : Boivin emphasizes the importance of considering the wider physical and social landscape, not just the images themselves.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on Cultural Transitions: Images from Texts and Archaeology, c. 2000–600 BCE - 3 - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What is the significance of pottery from Late Harappan levels at Bhorgarh, Delhi? |  |

| 2. What do the Copper Hoards represent in the context of ancient Indian archaeology? |  |

| 3. How do the Neolithic-Chalcolithic settlements in South India contribute to our understanding of early human societies? |  |

| 4. What are the main characteristics of Painted Grey Ware and its significance in Indian archaeology? |  |

| 5. What challenges exist in correlating literary and archaeological evidence for cultural transitions between 2000–600 BCE? |  |