Emerging Regional Configurations, c. 600–1200 CE - 4 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

The Hindu Cults

During the time when Shankara was writing, Advaita Vedanta was more about non-dualism than theism. However, in popular practice, people were mostly engaged in theistic worship, which led to the rise of a bhakti theology. Within Hinduism, while many gods like Surya, Ganesha, Karttikeya, and Brahma were worshipped, the Vaishnava, Shaiva, and Shakta cults became the most prominent. This period saw a rise in the number and spread of temples across different regions. The sculptures found in these temples displayed a wide variety of deity representations and a unified system of iconic forms that spanned India.

- Royal inscriptions from this time began to feature sectarian titles, and kings took an active role in patronizing temple construction, with some temples becoming closely associated with particular royal families.

- However, it’s important to note that royal patronage was not the only, nor the most significant, source of support for these religious establishments. Just like in earlier times, there were many non-royal groups who also contributed donations to religious causes.

- At one level, deities like Vishnu, Shiva, and Shakti were the focus of exclusive worship for devotees who considered them the supreme gods. At another level, these deities were part of a larger community of gods. This belief in a supreme god while acknowledging the existence of other gods, known as monolatory, is a key aspect of Hinduism. This is why, in addition to the main deity, Hindu temples often feature representations of various other gods as well.

Vishnuism and Shaivism

Vishnuism

- The concept of the ten incarnations of Vishnu was likely standardized during the early medieval period, as evidenced by texts and temple sculptures.

- Pancharatra texts elaborated on Vishnu's vyuhas (emanations), increasing their number from four to twenty-four.

- Krishna, the divine cowherd, became a central figure in Vishnuism. His life and exploits are detailed in texts like the Harivamsha and the Bhagavata Purana, particularly in Book 10, known as the Krishna-charita.

- The Bhagavata Purana, likely composed in South India during the 9th to 10th centuries, narrates Krishna's life, including his childhood with foster-parents Nanda and Yashodha, his cowherd life in Braja, and his miraculous deeds.

- The love story between Radha and Krishna, especially the gopis' (cowherd girls) love for Krishna, serves as a metaphor for the devotee's relationship with God in Krishna bhakti.

- Early texts like the Matsya, Varaha, and Linga Puranas mention Radha, but she gains prominence in the 12th-century poem Gita-Govinda by Jayadeva, which explores the love between Radha and Krishna.

- The theme is further developed in the later Brahmavaivarta Purana.

The ‘Durga’ Temple, Aihole

- The ‘Durga temple’ at Aihole, built around 725–730 CE during the Chalukya king Vijayaditya’s reign, is named after a nearby fort and is not dedicated to the goddess Durga.

- The temple features an apsidal form with an ambulatory passage along the outer side of the apse.

- The mandapa (hall) and verandah exhibit Dravida architectural style, while the shikhara (tower) represents a variant of the Nagara style.

- Inside the temple, the small sanctum has a rounded back and a raised circular altar.

- The original image of the presiding deity was removed at an unknown time.

Structure of the Durga Temple

The circumambulatory passage, or pradakshina-patha, around the temple features a gallery with a parapet and 28 square pillars, allowing ample air and light. The inner wall of the gallery has 11 niches framed by pilasters, showcasing relief sculptures, of which only seven have survived. These reliefs are considered masterpieces from the Chalukya period and depict various themes, including:

- Shiva with Nandi

- Vishnu in his Narasimha avatar

- Vishnu on Garuda

- Vishnu in his boar incarnation

- Durga Mahishasuramardini

- Hari-Hara (the combination of Vishnu and Shiva)

Cultic Affiliation

- Identifying the cultic affiliations of the Durga Temple is challenging due to the variety of sculptures present. Typically, Shaiva temples in the region feature a Nandi mandapa, which is absent here, indicating that it is not a Shiva temple. Similarly, the absence of a focus on the goddess suggests it is not a goddess temple either. Vaishnava temples from this period usually have exclusively Vaishnava themes, making it unlikely that this was a Vishnu temple.

- Many art historians believe that the Durga Temple was dedicated to Aditya (Surya). Evidence for this includes an image of the sun god above the entrance and a gateway inscription referring to the temple as dedicated to Aditya. Several representations of the sun god have also been found elsewhere on the structure. Despite the possibility of it being understood as a Surya temple, the form and style of the Durga Temple at Aihole remain unique in many respects.

Sculptural Depictions and Devotional Practices

Vishnu and His Avatars

- Sculptures of Vishnu in his various avatars have been discovered across different regions of the Indian subcontinent.

- Vishnu is frequently depicted alongside goddesses like Lakshmi (goddess of wealth), Sarasvati (goddess of knowledge), and Bhudevi (goddess of the earth).

Vaishnava Devotionalism

- Vaishnava devotion became particularly vibrant in South India through the hymns of the Alvars, poet-saints who composed devotional songs in praise of Vishnu.

- Many temples and sculptures dedicated to Vaishnavism are believed to have been created during the early medieval period.

Rise of Shaiva Worship and Philosophical Schools

- The growing popularity of Shiva worship led to the emergence of various philosophical schools within Shaivism, such as Shaiva Siddhanta, Kashmir Shaivism, and the Virashaiva tradition.

- These schools share similar ideas and regard the Agamas as authoritative texts, believed to contain the teachings of Shiva himself.

The Agamas

- The Agamas are considered sacred texts by followers of various Shaiva traditions, believed to contain the teachings of Shiva and meant for select initiates.

- These texts likely originated in the Tamil-speaking region between 400 and 800 CE.

Core Principles

- The Agamas emphasize bhakti (devotion) as the most important aspect, along with knowledge (jnana), ritual (kriya), and yogic practice (charya).

- While acknowledging the Vedic tradition, they prioritize Shaiva bhakti over Vedic sacrifices.

Rituals and Temples

- The Agamas prescribe rituals for home and temple worship, primarily using Shaiva mantras, with some Vedic mantras included.

- They also provide guidelines for making religious images and constructing temples.

Shaiva Siddhanta

- Shaiva Siddhanta is a prominent Shaiva philosophical school in South India.

- It recognizes three eternal principles: God (Shiva), the universe, and souls.

- Shiva is believed to have created the world through his will and energy (shakti).

- The school accepts the authority of the Vedas, Agamas, and the hymns of saints but interprets the Vedic tradition through the lens of Shaiva bhakti.

Kashmir Shaivism

- The Kashmir Shaiva school is known for its monistic or non-dualistic philosophy, which posits that the atman (individual soul) and the world are identical with Shiva.

- The universe is seen as a manifestation of Shiva, created through his creative power, akin to a reflection in a mirror.

- Shakti represents the feminine aspect of the divine.

- The foundational texts of this school include the Shivasutras, believed to have been revealed by Shiva to the sage Vasugupta in the 8th or 9th century.

- Prominent figures in this tradition include Abhinavagupta, Utpala, and Ramakantha, who further developed its philosophical concepts.

The Shakti Cult

The Devi-Mahatmya, added to the Markandeya Purana around the 7th century, praises the goddess and recounts her victories, like defeating the buffalo demon Mahishasura. The text includes hymns that celebrate her various forms and powers, such as the Narayani-stuti, which highlights her role in sustaining the universe.

The goddess prophesies her future incarnations, promising to return to Earth to combat evil, similar to themes in the Bhagavad Gita.

The Goddess as Killer of the Demon Mahisha

- The Durga-saptashati, consisting of 700 verses in the Markandeya Purana, extols the goddess and recounts her numerous victories. One particular instance describes her fierce battle with the buffalo demon Mahisha. In this depiction, she is known as Durga Mahishasuramardini, which means Durga, the slayer of the demon Mahisha.

- The core iconography of Durga Mahishasuramardini, which is the most commonly depicted form of the goddess in sculptures, was established in the early centuries of the Common Era (CE). However, within these broad iconographic guidelines, ancient craftsmen made individual choices regarding details and portrayals, giving their creations a unique touch. Some of the most remarkable sculptures of Durga Mahishasuramardini were crafted by artisans during the early medieval period.

Sculptural representations of the goddess exhibit variations on the fundamental theme. These variations include:

- Number of Arms: The number of arms the goddess is depicted with can vary.

- Lion as Mount or Companion: In some sculptures, the lion appears as her mount, while in others, it is depicted by her side.

- Buffalo Demon Depiction: The buffalo demon may be shown as a full animal in some representations, while in others, he is depicted as a creature that is part man and part animal.

- Conveying Strength vs. Grace: Some representations emphasize the goddess's strength and vigor, while others successfully convey her gracefulness and femininity.

- One of the most striking representations of Durga Mahishasuramardini is found in a niche within the Virupaksha temple at Aihole. This carving stands out due to its deep relief, almost achieving a three-dimensional effect. In this depiction, the demon is portrayed as a human with buffalo horns, adding to the dramatic impact of the scene.

- Goddess Durga is depicted in a powerful and dynamic pose, with her head pressed down under her foot. Her arms are positioned in a rhythmic manner, showcasing her strength and grace. With effortless precision, she wields her sword, cleaving through the demon’s body. The sculptor has captured an image that is not only graceful and realistic but also exudes a sense of power.

- Architectural and sculptural remnants from various regions of the subcontinent indicate the widespread veneration of Durga, along with the associated cults of the Matrikas and the Yoginis. The Matrikas, usually numbered seven or eight, are described in Chapter 9. The Yoginis, eventually recognized as 64 in number, are depicted in texts as attendants or manifestations of Durga during her battles against the demons Shumbha and Nishumbha. The principal Yoginis were identified with the Matrikas.

- From this period, there is an abundance of multi-armed Durga images, particularly in eastern India. In Tamil Nadu, a distinctive iconographic feature is the association of the goddess with a stag. Representations of Durga as Nishumbhamardini, the slayer of the demon Nishumbha, are found in reliefs at numerous temples from the Chola period. The worship of the Sapta-Matrikas and Yoginis was also prevalent in eastern India. In Orissa, several Matrika images have been discovered in and around Jajpur, and hypaethral temples dedicated to the Yoginis are located at Ranipur Jharial and Hirapur.

- Early medieval inscriptions in India mention various local goddesses, such as Viraja and Stambheshvari in Orissa, and Kamakhya in Assam. The Puranic tradition unified these local goddess cults by portraying them as different manifestations of the supreme goddess, the great Devi. Research by Kunal Chakrabarti has shown that in Bengal, the interaction between Brahmanism and a strong tradition of autonomous goddess worship led to a cultural synthesis that prioritized goddess worship. The Matsya Purana lists 108 names of the great goddess, while the Kurma Purana invokes her with 1,000 names.

- The Kalika Purana, an important Shakta text from the early medieval period, reflects the diverse forms of Devi worship. The goddess is described in both her benign and terrifying forms. In her shanta (calm) form, she possesses a strongly erotic character, while in her raudra (fierce) form, she is best worshipped in a cremation ground. The Purana outlines the dakshina-bhava (right method) and vama-bhava (left method) of worship, both of which have a Tantric influence, with the latter being stronger. The right method involves regular rites and rituals, including animal and human sacrifice, while the left method includes rituals involving alcohol, meat, and sexual rites. The Kalika Purana also provides details about the popular festival of Durga Puja.

South Indian Bhakti: The Alvars and Nayanmars

During the early medieval period, the Alvar and Nayanmar saints in South India brought a fresh emphasis and expression to Vaishnava and Shaiva devotionalism. Their approach was deeply rooted in the Tamil land, language, and ethos. The term "bhakti" in Sanskrit comes from the root "bhaj," meaning to share or participate. In this context, a "bhakta" is someone who shares or participates in the divine. However, the Tamil word used by Alvars and Nayanmars to express their devotion is "anbu," meaning love. The concept of bhakti or its Tamil version "patti" came later. The relationship between the devotee and god was seen as reciprocal, with "arul" referring to the love of the god for his devotee.

- The origins of South Indian bhakti can be traced to late Sangam poetry and elements in the Paripatal and Pattuppattu. For example, the Tirumurukarruppatai describes the god Murugan using epithets that highlight his mythology and encourages devotees to visit specific shrines dedicated to him. Zvelebil (1977) noted that the formal structure of bhakti poetry is rooted in the tanippatal, single bardic stanzas found in both akam and puram poems. There are also connections with the patan setting of heroic poems, where the focus shifts from praising a king to praising a god, beseeching him for deliverance.

- Traditionally, there were 12 Alvars and 63 Nayanmars whose hymns are still sung in temples today. The saints themselves are worshipped, a practice dating back to the Chola period. Images or paintings of the Nayanmars are typically found in temple halls around the sanctum and are venerated.

- Vishnu temples often have separate shrines for images of the Alvars. However, there is some uncertainty regarding the historicity of certain saints, making it challenging to separate fact from myth in their hagiographies. The male saints were not reclusive or ascetic; they lived as part of society, and most were married. The circumstances of the female saints, as will be discussed later, were different.

Introduction Alvar and Nayanmar Poetry

- Alvar and Nayanmar poetry is characterized by a deep and passionate devotion to God, expressed in various intimate and intense ways.

- The poets envisioned their deity in multiple roles, such as a friend, mother, father, master, teacher, and bridegroom.

- Male saints often adopted a feminine perspective, expressing their longing for union with God as a lover or bride. For instance, Manikkavachakar referred to his Lord as the eternal bridegroom, while Nammalvar described the Lord's overwhelming masculinity, which made the devotee lose his own sense of maleness.

Female Voice in Devotion

- Despite the male objects of devotion, the use of a female voice was deemed particularly suitable for expressing complete love and surrender, given the prevailing gender roles.

- There are a few instances where women saints assumed a male voice in their expressions of devotion.

Nayanmars and Shaiva Tradition

- Nayanmar is an honorific term. The Shaiva saints referred to themselves as atiyar (servant) or tontar (slave), indicating their self-perception as servants or slaves of Shiva.

- Among the 63 Nayanmars, three saints—Sambandar, Appar, and Sundarar —are considered especially significant and are sometimes housed in special shrines within temples, often accompanied by an image of Manikkavachakar.

Historical Context of Shaiva Poet-Saints

- The concept of a community of Shaiva poet-saints dates back to the early 8th century when Sundarar wrote the Tiruttondar Tokai, listing 62 Nayanmars.

- In the early 10th century, Nambi Andar Nambi composed the Tiruttondar Tiruvantai, providing short hagiographies of these saints and adding Sundarar’s name to the list.

- The Periyapuranam, compiled in the mid-12th century, gathered stories of the saints’ lives and forms the 12th book of the Tirumurai canon. The Tevaram, a collection of hymns, is part of this larger work.

Relationship between God and Devotee

- In Shaiva bhakti, the relationship between God and devotee is often likened to that of master and slave.

- Manikkavachakar's poems frequently depict the experience of 'melting' before the Lord, emphasizing the deprecation of the body and corporeal state.

- Ecstatic worship is described, where the devotee experiences intense emotions such as stammering, crying, dancing, and feeling as if he is melting.

- The tone of the poetry is frenzied, with the poet often criticizing himself for his shortcomings and addressing God in familiar, intimate terms. For example, Manikkavachakar threatens to call Shiva a madman if he abandons him.

Alvars and Their Hymns

- The term "Alvar" refers to those who immerse themselves deeply in the divine.

- In the 10th century, Nathamuni compiled the hymns of the 12 Alvars into the Nalayira Divya Prabandham, which became part of the Vaishnava canon.

Hagiography and Devotional Themes

- The first significant hagiography of the Alvar saints was written by Garudavahana in the 12th century and is known as the Divyasuricharitam.

- In Alvar bhakti, the relationship between the devotee and the deity, often referred to as Mayon or Mal (Krishna), was commonly expressed in terms of love between a lover and their beloved.

- In some cases, the relationship of a mother and child was also used to describe this bond.

Focus of Devotion

- For devotees of the lord, traditional religious practices such as sacrifices or actions deemed marks of piety were considered meaningless.

- The emphasis was solely on love for the god, without any other considerations.

Songs of the Nayanmar saint Appar

- On Shiva Bhakti:Appar, a saint devoted to Lord Shiva, questions the effectiveness of various religious practices and emphasizes the importance of faith and devotion to the Supreme Lord.

- Bathing in Sacred Rivers: Appar asks why one would bathe in holy rivers like the Ganga, Kaveri, or at Kumari, or even where the seas meet. He believes that seeing the Lord Supreme everywhere is what truly matters.

- Chanting the Vedas and Following Vedic Rituals: He questions the need to chant the Vedas, follow Vedic rituals, or preach the books of dharma daily. Instead, he emphasizes that constantly thinking of the Lord Supreme is what will help.

- Ascetic Practices: Appar wonders why one should roam forests, wander towns, perform strict penance, or fast and starve. He insists that having faith in the Lord of True Wisdom is what truly counts.

- Fetching Water from Tirthas: He criticizes the act of fetching water from a thousand tirthas as futile. It’s like a mindless fool guarding water in a leaking pot. What matters is loving the gracious Lord at all times.

- Appar on the Community of Bhaktas:Appar expresses his reverence for anyone who bows to Lord Shiva, regardless of their social status or appearance. He sees them as divine and worthy of worship, highlighting the inclusivity and depth of devotion in Shiva bhakti.

- Reverence for Shiva: Appar emphasizes that those who bow to Shiva, regardless of their circumstances, are worthy of respect and worship.

- Inclusivity: He acknowledges that even lepers, outcasts, or those who may engage in taboo practices, like eating beef, are deserving of reverence if they love Shiva.

- Personal Transformation: Appar’s willingness to bow and offer worship to such individuals reflects the transformative power of devotion and the idea that love for Shiva transcends social boundaries.

- Analysis of Mythological References in the Tiruvantatis:Friedhelm Hardy (1983) studied the mythological references in the Tiruvantatis, which represent an early stage of Alvar devotion. He pointed out the focus on the Krishna avatar during this period.

- Ritual Worship of Krishna: The devotees are depicted as serving, worshipping, praising, and adorning the image of Krishna, indicating ritual worship in a temple setting.

- Deity’s Immanence: There are references to the deity being present within the devotee, highlighting a close spiritual connection.

- Shift in Geographical Context: Hardy noted a shift in the geographical context of Alvar activity from the Venkatam-Kanchi area to South Tamil Nadu and South Kerala. This eventually expanded to a network of shrines along the coast from Venkatam to Kottiyur, culminating in a concentration in Shrirangam.

- External Structure for Bhakti: The foundation for this bhakti movement was provided by approximately 95 temples that supported and facilitated the growing devotion.

- Nammalvar's Poems and the Devotee-Deity Relationship:Nammalvar, an earlier saint, used the style of ancient akam poems but introduced new symbolism. He portrayed the relationship between the devotee and the deity as similar to that between lovers.

- Emotional and Erotic Emphasis: This analogy allowed for an emotional and erotic emphasis in the poetry, drawing from the mythology of Krishna and his interactions with the gopis, including one named Pinnai.

- Kodai (Andal) and the Pangs of Separation: The erotic element was most pronounced in the poems of Kodai, a woman-saint known as Andal. Her poems are filled with themes of separation and longing for union with her lord, adding a deeply personal and emotional layer to the devotion.

Women and Salvation

The relationship between women and salvation is complex and problematic across all religious traditions. In South Indian bhakti, historians like Uma Chakravarti and Vijaya Ramaswamy have highlighted fundamental differences in the experiences of bhakti for men and women.

Bhakti Tradition

Experiences of Bhakti for Men and Women

- Male Saints: For male saints, there was no conflict between being a householder and being devoted to God. Their roles as husbands and fathers did not hinder their spiritual practice.

- Female Bhaktins: In contrast, the female body posed a significant challenge for bhaktins. Factors like youth and beauty were seen as burdens, and bhaktins found it difficult to balance marriage, family, and devotion.

Contested Claims:

- Women’s claims to asceticism, priesthood, and salvation have historically been contested. Women often had to sever ties with their families to respond to their spiritual calling, risking being labeled as rebels and deviants.

Social Significance of Bhakti Tradition

- To understand the social significance and impact of the bhakti tradition, it is essential to look beyond the leadership and examine the ideas expressed in bhakti songs and the expansion of social access to sacred space.

- Leadership and Social Relations:

- Bhakti leadership was dominated by elite groups, particularly Brahmanas, and did not overturn existing social relations. However, it created a religious community where traditional social distinctions could be transcended, at least in the relationship between the bhakta and their god.

Community of Bhaktas

- The idea of a community of bhaktas, such as bhakta kulam or tondai kulam, is strongly expressed in the songs of some saints. This concept emphasizes the collective identity of bhaktas, transcending individual social distinctions in their relationship with the divine.

Philsophical Aspect of Alvar Vaishnava Bhakti

Nathamuni, the founder of the Shrivaishnava sect and a key figure in the late 10th to early 11th century, was born in Viranarayanapura and later lived in Shrirangam. In his work Nyayatattva, he highlighted the concept of prapatti, which means complete surrender to God.

Following Nathamuni, other influential Srivaishnava acharyas included:

- Yamunacharya (10th century)

- Ramanuja (11th–12th centuries)

- Madhva (12th/13th century)

Contribution of Ramanuja

Ramanuja, an important figure in this tradition, initially lived in Kanchipuram but later settled in Shrirangam. His life was marked by persecution, particularly by a Chola king who favored Shiva. Seeking refuge, Ramanuja found support in the court of a Hoysala king.

He authored several significant works, including:

- Vedantasara

- Vedarthasamgraha

- Vedantadipa

- Commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahmasutra

Philosophy of Ramanuja

- Ramanuja's philosophical system, known as Vishishtadvaita or qualified non-dualism, integrated Vaishnava bhakti with the monistic ideas of the Upanishads.

- In this framework, Brahman is understood to possess qualities (sa-guna ), making Him accessible to devotees through bhakti.

- The relationship between Brahman and individual souls (atman ) is illustrated through the analogy of a rose and its redness. Just as a red rose cannot exist without its redness, Brahman cannot exist without the atman.

- While atman and Brahman are distinct, they are also inseparable, highlighting their interdependent relationship.

Contribution of Madhva

Madhva, another significant acharya, made his mark by writing commentaries on the Brahmasutra and the Upanishads, along with a notable work called Bharatatatparyanirnaya, which was based on the Puranas and epics.

- Madhva's philosophy diverged from certain mainstream ideas by rejecting the notion that God is the material cause of the world's creation.

- He proposed a clear distinction between God, the individual soul, and the world, emphasizing their differences.

- While he acknowledged the flaws of the individual soul, he believed that near-perfection could be achieved through serving and worshipping God.

- Madhva's understanding of the relationship between God and the soul was akin to that of a master and servant, highlighting the hierarchical nature of their relationship.

Shaiva Siddhanta

Shaiva Siddhanta was another prominent school of Shaivism that gained popularity in South India during the early medieval period. This school focused on explaining the philosophical and metaphysical aspects of Shaiva bhakti.

Notable exponents of Shaiva Siddhanta in the South included:

- Meykandadeva

- Arulnandi Shivacharya

- Marai Jnana Sambandhar

- Umapati Shivacharya

One of the foundational texts of the school is the Shivajnanabodham, written by Meykanda in the 13th century. This work outlines the core doctrines of Shaiva Siddhanta.

The Vira Shaiva or Lingayat Movement

- In the early medieval period, the Virashaiva or Lingayat movement emerged and gained popularity. This sect originated around the 12th century in north-western Karnataka.

- Although it was largely led by Brahmanas, its main support came from artisans, traders, and farmers. The movement was anti-caste and anti-Brahmanical, rejecting the Vedic tradition, sacrifices, rituals, social customs, and superstitions.

- While promoting ahimsa (non-violence), it critiqued Jainism, which was influential in Karnataka. The sect traced its lineage to five legendary teachers: Renuka, Daruka, Ghantakarna, Dhenukarna, and Vishvakarna. However, Basavanna played a significant role in popularizing the movement in Karnataka. Akka-Mahadevi was a notable woman saint from this tradition.

Beliefs and Practices

- The Virashaiva movement rejected the Vedic tradition and its associated practices.

- It emphasized devotion to Shiva and accepted many doctrines of other Shaiva schools.

- Core ideas were expressed through vachanas (free verse lyrics) composed by saints.

- Male and female members wear a linga called the ishta-linga and do not prioritize temple worship.

- The movement emphasized love and kindness, but the greatest focus was on devotion to Shiva.

Expansion

- From its roots in Karnataka, the Virashaiva movement spread to other parts of South India.

Patronage to Temples

The construction and enhancement of religious establishments were made possible through patronage from various sources. Hermann Kulke ( [1993], 2001 ) highlighted that early medieval kings sought to reinforce their authority by extending patronage to major pilgrimage sites ( tirthas ), making substantial grants to temples, and constructing imperial temples.

Royal Patronage

Specific Shrines

- Royal patronage was crucial for specific shrines, reflecting the close relationship kings aimed to establish with certain deities and temples.

- Example: The Brihadishvara temple at Tanjavur (Tanjore), built under royal direction.

Orissa

Lingaraja Temple

- Largest temple in Bhubaneshwar, traditionally believed to have taken three generations of Somavamshi kings to complete.

- Orissa was predominantly Shaiva until the 12th century.

Purushottama Cult

- 12th-century elevation of the deity Purushottama (later Jagannatha) to an imperial cult status.

- Purushottama Temple at Puri, built by Ganga king Anantavarman Chodaganga, aimed to surpass the Brihadishvara temple in grandeur.

Anangabhima III

- In 1230 CE, he dedicated his empire to Purushottama, considering himself the god’s deputy.

Independence of Trajectories

- Overall, the development of temple building and architecture in Orissa was largely independent of political history and patronage fluctuations.

South India

- Numerous inscriptions document royal donations to temples, primarily of gold, land, livestock, and paddy.

- The volume of such donations significantly increased from the Pallava to the Chola periods.

Example: Tirupati Inscriptions

- Pallavas: 11 donations

- Cholas: 31 donations

Royal Land Grants

- Land grants to temples were made in perpetuity, accompanied by tax exemptions and privileges.

- Temples also leased land to tenants.

Example: Sundara Chola Inscription

- Temple management granted 124 veli of devadana land to a tenant, who was to provide 2,880 kalam of rice annually to the temple.

- Rate: 120 kalam per veli

During the Chola period, many temples expanded significantly due to generous royal support. The Mukteshvara temple was the largest Pallava temple, employing 54 people, while the Brihadishvara temple in Tanjavur had over 600 employees, including dancers, drummers, tailors, goldsmiths, and accountants. Temple workers were usually paid in rice, and some received revenue assignments during the Chola period.

Lingaraja Temple, Bhubaneswar (Orissa)

- Some scholars argue that the rise of temples as landowners in South India and the increase in pariharas indicate growing oppression of peasants and the development of feudal agrarian relations. They believe that temples became centers of political power, contributing to the decentralization of authority. However, it is clear that the relationship between kings and temples was one of alliance, not rivalry. Supporting temples was a key way for kings to gain, announce, and maintain political legitimacy.

- Temple patrons included chieftains, landowners, merchants, villages, and town assemblies. Merchants often donated money, livestock, and sometimes gold and silver ornaments, usually for the upkeep of perpetual lamps in temples. For instance, during the reign of Parantaka I, a merchant’s wife donated 30 kashu (possibly copper coins) for a perpetual lamp, and another inscription records a merchant giving 90 sheep for a similar purpose. There are also instances of merchants gifting land to temples, sometimes after purchasing it.

- Merchant guilds also made donations during the Chola period, with inscriptions recording gifts from groups like the Manigramam of Kodambalur and the Dharmavaniyar and Valanjiyar of Tennilangai. Additionally, some artisan groups were involved in temple management, such as the weavers of Kanchipuram, who were tasked with overseeing the local temple’s financial and other affairs during the reign of Uttama Chola (970–85 CE).

Jagannatha Temple, Puri (Orissa)

- Donation patterns to religious establishments provide insights into women’s participation in religious life from a social history perspective. Leslie Orr (2000b) examined the epigraphic evidence of women’s patronage in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism in Tamil Nadu between c. 700 and 1700.

- Due to the decline of Jaina and Buddhist establishments, there is more information available about Hindu temples. Women appear as donors in all three religious traditions, with a similar social background. The donors included religious women (nuns, temple women), queens, women from chieftain families, and wives of landowners, merchants, and Brahmanas.

- Donations were primarily directed towards supporting worship in shrines, such as temple construction, image making, and providing lamps, flowers, food for the deity, and support for temple services. Orr suggests that instead of seeking female counterparts to priests and monks, it is important to recognize the significance of gift-giving as a religious activity. The evidence of women donors across various religious traditions indicates active participation rather than marginalization.

Temple Women in Chola Inscriptions

- Leslie Orr's research indicates that the "temple women" during the Chola period were distinct from the devadasis of the 20th century. Interestingly, while there are a few earlier instances, the term devadasi seems to have gained popularity only in the early 20th century.

- In Chola period inscriptions, temple women were referred to as tevaratiyar (devotee of god), tevanar makal (daughter of god), and taliyilar or patiyilar (woman of the temple). Their identity was not determined by birth, caste, professional skill, or ritual function, but by their connection to a temple, deity, or place.

- These women were not typically involved in performing rituals or managing temple activities. While there are instances of them performing minor or menial services, there was a growing presence of slave women working within temples. Generally, temple women were linked to temples, particularly those in their native villages or towns, through their donations.

- They are prominently featured in inscriptions, especially in the 12th and 13th centuries, with a stronger presence in northern and southern Tamil Nadu. Although closely associated with towns like Kanchipuram, temple women were more commonly linked to small temple establishments.

- During the late Chola period, these women gained certain privileges and honors in return for their donations, such as the right to a place close to the deity in processions or the privilege of singing specific parts of hymns before the deity. Such honors appear to have become hereditary over time. Notably, Chola period temple women did not seem to be married.

- In the early Chola period, temple women primarily made gifts to cover the costs of maintaining perpetual lamps. By the late Chola period, their donations also supported daily and festive services in the temple, temple personnel, temple construction, and the creation and installation of images. In these aspects, their gifts were similar to those made by other categories of donors, regardless of gender.

- Inscriptions from the Chola period suggest that women had access to and control over the economic resources of their households. Orr proposes that while women in general became less visible as donors in Chola inscriptions, temple women remained consistently visible.

Devadasis and Temple Women: A Comparison

- Modern Devadasis: Today, devadasis are recognized for their hereditary roles, professional skills, and dedication to temples. This means that their work and commitment to the temple are passed down through generations, and they are trained professionals in their field.

- Temple Women in the Chola Period: In contrast, the temple women during the Chola period were not involved in the same practices as modern devadasis. They were neither temple dancers nor engaged in prostitution. Their roles and activities were different from what we see in the modern context.

- Marital Status and Sexual Activity: Temple women in the Chola period were not married to the god, nor is there any evidence to suggest that their sexual activities were limited to or exploited within the temple setting. Their personal lives and activities were not confined to the temple context.

- Historical Perspective: The history of temple women in the Chola period should not be viewed as a story of decline or degeneration. In fact, their position and status became stronger and more established over time. This indicates that their role was significant and respected, rather than diminishing.

Temple Architecture in Early Medieval India: Nagara, Dravida, and Vesara Styles

During the early medieval period, India witnessed significant advancements in art and architecture, leading to the emergence of distinct regional architectural and sculptural styles in areas like Kashmir, Rajasthan, and Orissa. In peninsular India, major edifices were constructed under the patronage of various dynasties, including the Rashtrakutas, early Western Chalukyas, Pallavas, Hoysalas, and Cholas. Unlike earlier centuries dominated by Buddhist architecture, this period saw a prevalence of Hindu temple remains.

Architectural texts known as the Shilpashastras were written during this time, referring to three major styles of temple architecture: Nagara, Dravida, and Vesara.

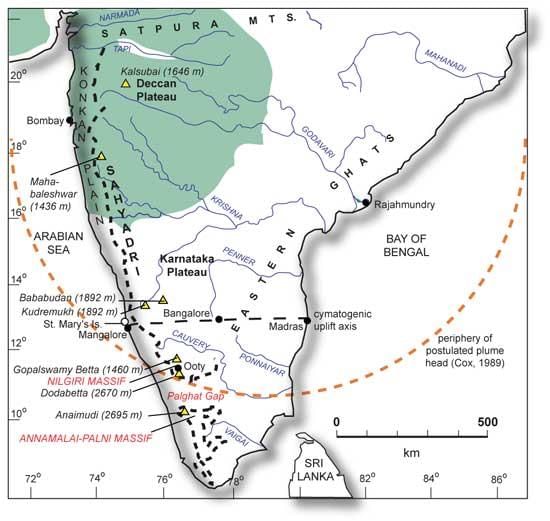

- Nagara Style: Associated with the region between the Himalayas and the Vindhyas, characterized by a square plan with projections, a curvilinear shikhara (temple tower), and a cruciform shape.

- Dravida Style: Linked to the area between the Krishna and Kaveri rivers, known for its distinctive architectural features.

- Vesara Style: Sometimes related to the region between the Vindhyas and the Krishna river, though the term 'Karnata-Dravida' is preferred for Chalukya temples in the Deccan.

Basic Features of the Nagara Temple

- Plan: Square with projections on each side, creating a cruciform shape.

- Elevation: Marked by a conical or convex shikhara, consisting of layers of carved courses, often crowned by an amalaka (notched ring stone).

Historical Development

- Early Examples: Cruciform plan and curvilinear shikhara seen in northern temples from the 6th century CE, such as the Dashavatara temple at Deogarh and the brick temple at Bhitargaon.

- Beginnings of Nagara Shikhara: Observed in the Mahadeva temple at Nachna Kuthara (7th century) and the brick Lakshmana temple at Sirpur.

- Fully Developed Nagara Style: Evident by the 8th century.

Dravida Style Temples:

- Shikhara: The Dravida temple is known for its distinctive pyramidal shikhara. This shikhara features multiple tiers that are progressively smaller, leading to a slender pinnacle topped with a small dome called a stupika.

- Later Developments: Over time, South Indian temples became characterized by large gateways known as gopurams, as well as pillared halls and corridors.

- Historical Origins: The earliest instances of these features date back to the Gupta period and were not limited to southern India. They can be found in northern and central India, as well as the Deccan region. Examples include the Parvati temple at Nachna Kuthara and the Lad Khan, Kont Gudi, and Meguti temples at Aihole.

- Temple Structure: In temples built in the Dravida style, the square inner sanctum is placed within a large covered enclosure. The external walls of these temples are adorned with pilasters that create niches.

Vesara Style Temples:

- Hybrid Nature: The Vesara style is a hybrid architectural style that incorporates elements from both northern and southern temple styles. The term "vesara" means "mule," signifying the mixed nature of this style.

- Variability: The combination of northern and southern elements in Vesara temples can vary, making it challenging to define a specific template for this style.

Examples: Temples built in the Deccan region under the later Chalukyas of Kalyani and the Hoysalas are considered prime examples of the Vesara style. - Distinctiveness: While Vesara temples are a blend of northern and southern styles, they also possess unique characteristics and variations that set them apart.

Overview of Indian Temple Architecture:

- Deccan and Far South: The subsequent sections will provide a brief overview of Indian temple architecture in the Deccan region and the far south.

- Chola Period Metal Sculpture: Additionally, there will be a discussion on the metal sculpture of the Chola period, showcasing the artistic achievements of this era.

Western India and the Deccan

Ellora Caves:

- Last phase of Buddhist cave architecture in western India.

- Continuities with earlier sites like Ajanta, Bagh, and Kanheri, but with notable changes.

- Increased size of side shrines and features like a double row of stone benches in Cave 5.

- Cave 12 (Tin Thal) represents the climax of cave excavations at Ellora with its larger scale and rich sculpture.

- Sculptural programme includes arrays of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, sometimes arranged in a mandala formation.

Kailashanatha Temple at Ellora:

- Excavated in the late 8th century under the Rashtrakutas, this Shiva temple is a complex with a main shrine, Nandi pavilion, subsidiary shrines, and cloisters.

- Superstructure reflects Dravida style architecture.

- Richly ornamented surfaces with bold and fine sculptures, mostly Shaiva, but also Vaishnava representations.

- Notable sculptures include Shiva, Ravana shaking Mount Kailasha, Durga, and goddesses like Ganga, Yamuna, and Sarasvati.

- Marks the highest point of rock-cut temple architecture in the subcontinent.

Early Medieval Rock-Cut Shrines and Structural Shrines in Karnataka:

- Early architectural phase (6th–early 8th centuries) represented at Badami and Aihole.

- Later and grander 8th century temples located at Pattadakal.

- Badami was the site of Vatapi, the capital of the early Western Chalukyas.

- Temple architecture in the Deccan shows a mix of northern and southern features but developed a distinctive identity during these centuries.

Aihole

- Aihole features two significant cave shrines, one dedicated to Shaiva and the other to Jaina, both boasting intricately adorned interiors.

- The Shaiva cave, known as the Ravanaphadi cave, includes a central hall, two side shrine sections, and a garbhagriha housing a linga.

- The walls and part of the ceiling showcase sculptures, including Shiva as Nataraja and the Sapta-Matrikas.

- Compared to figures at Ellora and Badami, those in Aihole are more slender with tall crowns.

- Outside the cave entrance, there are carvings of dwarfs and doorkeepers in Scythian-style attire.

Badami

- The rock-cut caves at Badami, carved into red sandstone overlooking a tank, include three major caves with the largest dedicated to Vaishnava, while the others are Shaiva and Jaina.

- The caves feature a simple layout of a verandah, pillared hall, and small sanctum, with walls and ceilings adorned with carvings.

- Cave 3 is notable for its large reliefs of Vishnu incarnations, such as Varaha, Narasimha, and Vamana, along with intricate mithuna figures.

Structural Temples

- The period's structural temples were primarily built from large stone blocks without mortar, featuring sculptural decoration on inner walls and ceilings.

- Aihole houses many major temples with varied plans, including the Meguti temple with Pulakeshin II's inscription, the apsidal Durga temple, and the Lad Khan temple with a pillared porch and concentric square halls.

- Mahakuta, near Badami, has around 20 early Western Chalukya temples with northern style curvilinear shikharas.

Pattadakal

- Located 16 km from Badami, Pattadakal's temples represent an evolution of Deccan temple architecture and sculpture.

- The Virupaksha temple, dedicated to Shiva and built by Lokamahadevi, features a pillared hall, porch extensions, antechamber, and sanctum with circumambulation passage in the Dravida style.

- The temple's outer walls display deep carvings, mainly of Shiva, with an elaborately carved sanctum doorway.

Discovery of an Early Medieval Quarry Site Near Pattadakal

A team of archaeologists led by S. V. Venkateshaiah from the Archaeological Survey of India recently uncovered a significant quarry site thought to be the source of stone for the famous temples at Pattadakal. This site is located about 5 kilometers north of Pattadakal, in an area with hilly sandstone outcrops.

Findings at the Quarry Site

- The quarry site features clear evidence of systematic and planned stone extraction, including terraces, abandoned rocks, and blocks deemed unsuitable for use.

- Archaeologists found standard-sized wedge marks made by masons to outline stones for cutting, as well as blocks in regular dimensions and irregular shapes.

- Tools used in the quarrying process were also discovered, along with stone blocks that matched the dimensions of slabs used in the Pattadakal temples.

- Some blocks were found neatly piled, presumably ready for transport to the temple site.

- Engravings and label inscriptions dated to the mid-8th century CE were identified, providing clues about the quarry's historical context.

Inscriptions and Guild Names

- The temples in Aihole, Pattadakal, and Badami mention guilds of architects and sculptors, as well as individual craftsmen. The quarry site offers names of individuals who may have been involved in the quarrying process.

- Inscriptions found at the site, often on the surfaces of rocks from which blocks were removed, likely mark resting spots for artisans.

Notable Inscriptions

- One significant inscription mentions two quarrymen, Dharmma Papaka and Anjuva, members of a guild of quarrymen and devotees of the god Shiva.

- Other inscriptions record names such as Bhribhrigu, Srinidhi Purusha, Sri Ovajarasa, and Vira Vidyadhara.

Masons' Marks

- Various masons’ marks were discovered at the site, some of which may have identified specific craftspeople or guilds.

- Marks like the conch and trishula could signify individual craftsmen, while others, such as circles with lines radiating from them, might indicate architectural features like pillars or beams.

- Similar marks have been found in some of the temples at Pattadakal, suggesting a connection between the quarry and the temple construction sites.

Rough Drawings and Carvings

- Deities: There are rough drawings of deities such as Ganesha, Mahishasuramardini, Shiva lingas, and Nandi bulls on the rock face.

- Animals: Stylized carvings of animals like lions, peacocks, and possibly a camel have been identified.

- Architectural Members: Engravings of architectural features like chaitya arches and pillars are present.

- Sculptural Motifs: Various sculptural motifs including purna-ghatas, conches, a svastika, and tridents are also found.

Comparison with Pattadakal Temples

- There are some broad similarities between the themes of these carvings and those found on the Pattadakal temples.

- However, the work at the quarrying site is clearly ‘rough work’ and does not match the finished excellence seen at the temple site.

Discovery of Steel Tools

- Significant steel tools such as a truncated triangular wedge and a hammer or pitcher gun were discovered at the site.

- These tools were found buried in debris containing waste flakes and humus, about 15–20 cm from the surface.

- The size of the wedge tool matches exactly with the size of the wedge marks found at the site.

- Small trough-shaped stone objects found nearby may have been used to rapidly cool the heated wedges for tempering.

Hoysala Dynasty and Temple Architecture

- The Hoysala dynasty, ruling over southern Karnataka from its capital at Dorasamudra (modern Halebid), is associated with a later phase of temple architecture in the Deccan.

- Temples from this period, found at Halebid, Belur, and Somnathpur, are known for their exquisite, intricate, and detailed carvings on smooth chlorite schist.

- The Hoysaleshvara temple at Halebid, dating to the 12th century, features two nearly identical shrines with a cruciform plan, resting on cruciform-shaped plinths.

- The Keshava temple at Belur, built in the early 12th century, includes a complex of shrines within a large courtyard, with a cruciform pillared mandapa resting on a plinth.

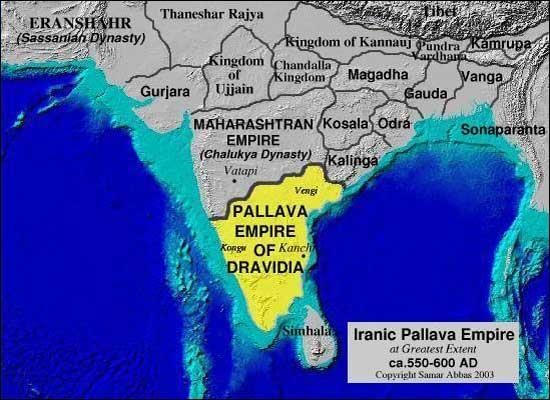

The Pallava Kingdom

The Pallava Kingdom, which lasted from the 4th to the 9th centuries CE, was a significant early medieval power in South India. The Pallavas were initially feudatories of the early Western Chalukyas and gradually rose to prominence, becoming a dominant force in the region.

- The kingdom is particularly renowned for its contributions to architecture and sculpture, especially during the reigns of kings like Mahendravarman I, Narasimhavarman I, and Narasimhavarman II Rajasimha. The Pallavas were instrumental in the development of rock-cut architecture and temple construction, with a distinctive style that set them apart from other contemporary dynasties. Mahendravarman I (600–625 CE) Narasimhavarman I (625–670 CE) Narasimhavarman II Rajasimha (700–728 CE)

- The history of stone architecture in South India starts in the 7th century and is linked to the growing popularity of bhakti cults. The Pallava kings, especially Mahendravarman I, Narasimhavarman I, and Narasimhavarman II Rajasimha, were significant supporters of the arts. Most of the remaining architecture from the Pallava period is found in Mamallapuram and Kanchipuram. This architecture includes cave temples, monolithic temples, and structural temples.

Pallava Cave Shrines

- The Pallava cave shrines are smaller and less intricate than those found at Ajanta and Ellora.

- They are relatively plain, with notable examples including the Lakshitayatana temple at Mandgappattu, Lalitankura’s cave at Tiruchirapalli, and various caves at Mamallapuram.

- The massive pillars in these caves are square at the bottom and top, chamfered into an octagonal shape in between.

- The cave façade is generally plain, with dvarapalas marking the two ends.

- The larger caves feature columns inside, leading to a sanctum guarded by dvarapalas and dvarapalikas.

- The sanctum typically contains a linga or images of deities such as Shiva, Vishnu, or Brahma.

- Relief carvings of deities are also present on the walls, with notable examples like the scene of Shiva receiving Ganga in the Tiruchirapalli cave.

Historical Significance of Mamallapuram:

- Artistic Heritage: The rock-cut sculptures and temples of Mamallapuram represent a high point in ancient Indian art and architecture. They reflect the skill and creativity of artisans who carved intricate details into stone, creating lasting masterpieces.

- Religious and Cultural Importance: The sculptures often depict Hindu deities, mythological stories, and religious themes, showcasing the spiritual beliefs and practices of the time. They provide insights into the cultural and religious landscape of ancient India.

- Architectural Innovation: The transition from rock-cut caves to free-standing temples and monolithic structures marks an important phase in the evolution of Indian architecture. Mamallapuram played a crucial role in this architectural journey.

- Influence on Later Architecture: The styles and techniques seen in Mamallapuram's sculptures and temples influenced later periods of Indian architecture, making it a significant reference point for scholars and architects.

- UNESCO World Heritage Status: The recognition of Mamallapuram as a UNESCO World Heritage Site underscores its global significance. It highlights the need to preserve and celebrate this important aspect of human history.

Key Features of Mamallapuram:

- Rock-Cut Temples: The town is famous for its rock-cut temples, which are carved directly into granite hills. These temples showcase intricate sculptures and are dedicated to various Hindu deities.

- Monolithic Sculptures: Mamallapuram is known for its monolithic sculptures, including the famous Arjuna's Penance, which depicts a scene from the Indian epic Mahabharata. These sculptures are carved from a single rock and display remarkable artistry.

- Shore Temple: The Shore Temple is one of the oldest stone temples in South India and is dedicated to Lord Shiva. It is located on the beach and offers stunning views of the Bay of Bengal.

- Pancha Rathas: This UNESCO World Heritage Site features five monolithic rock-cut temples, each resembling a chariot (ratha) and dedicated to different deities. The architecture and carvings of these temples are unique and reflect the craftsmanship of the era.

- Historical Significance: Mamallapuram was an important port city during the Pallava dynasty and played a crucial role in trade and commerce. The town's historical significance is evident in its architecture and cultural heritage.

- Festivals and Culture: Mamallapuram hosts various cultural festivals and events that celebrate its heritage. Traditional music, dance, and art forms are an integral part of the town's cultural fabric.

- Beach and Tourism: The town's proximity to the beach and its historical attractions make it a popular tourist destination. Visitors can enjoy the beautiful coastline while exploring the rich history of Mamallapuram.

The Chola Temples

Chola temples are primarily found in the southern region of India, particularly around Tanjore. Unlike the Pallava temples, which are mostly in and around Kanchipuram, Chola temples do not show a simple evolution from the earlier styles and incorporate new features. During the Chola period, many brick temples from Pallava times were rebuilt in stone.

Phases of Chola Temple Architecture: Historians generally divide the temple architecture of the Chola period into two main phases:

- Early Phase: Mid-9th to early 11th centuries

- Late Phase: Early 11th to 13th centuries Some art historians propose a more detailed division into three phases:

- Early: 850–985

- Middle: 985–1070

- Late: 1070–1270

- Early Chola Temples: The earliest Chola temples, such as the Shiva temple at Narttamalai, feature a vimana (sanctum and its superstructure) connected to an ardhamandapa (hall preceding the sanctum). These temples often included subsidiary shrines, known as parivaralayas, surrounding the main shrine. The outer walls of early Chola temples had minimal sculptural ornamentation, with some featuring dvarapalas (door guardians) and pilasters but lacking niches with deity images.

- Temples of Aditya I and Parantaka I: During the reigns of Aditya I and Parantaka I, several notable temples were built, including the Brahmapureshvara temple at Pullamangai, the Nageshvarasvami temple at Kumbakonam, and the Koranganatha temple at Srinivasanallur. The Brahmapureshvara temple, for example, features an ardhamandapa connected to the vimana, with a mukhamandapa (porch) added later.

- The temple’s outer walls are adorned with inverted lotuses, a frieze of lions, and niches (devakoshthas) containing images of deities like Ganesha, Durga Mahishasuramardini, and Brahma. The figures in these niches are characterized by their natural and slender forms with high headdresses. The outer walls also depict various mythological scenes, including those from the Ramayana.

Nageshvarasvami Temple

- The Nageshvarasvami temple originally had a simple structure with a connected ardhamandapa (a type of entrance hall) and vimana (the tower above the sanctum).

- The niches in the temple are decorated with intricately carved images of deities.

Koranganatha Temple

- The Koranganatha temple follows a similar basic design to the Nageshvarasvami temple.

- However, it features an antarala (a vestibule or antechamber) between the vimana and ardhamandapa, which is an addition not found in the Nageshvarasvami temple.

- The frieze along the outer base of the Koranganatha temple is adorned with rows of inverted lotuses, lions, and elephants.

- The sculpted figures on this temple are more elaborately decorated compared to those in other temples from the same period.

Third Phase of Chola Temple Architecture

- Shembiyan Mahadevi, a queen and significant patron of temple construction, is associated with the third phase of Chola temple architecture.

- During the reigns of her husband Gandaraditya (949–57 CE), her son Uttama I (969–85 CE), and early in Rajaraja I’s reign, many older brick temples were rebuilt in stone.

- A notable change in this period is the style of sculpted figures, which appear more rigid and lifeless compared to earlier works.

- One example of a temple built under the patronage of Shembiyan Mahadevi is the Agastyeshvara temple at Anangapur.

Sculptural Detail

- Brihadishvara Temple, Tanjavur: Gopura

- Plan of Brihadishvara Temple

- Relief Panels, Brihadishvara Temple, Tanjavur

- Rajendra I, the son of Rajaraja, constructed a temple named Brihadishvara in his newly established capital, Gangaikondacholapuram. Although the temple was unfinished and now in a state of ruin, enough of it remains to demonstrate the uneven quality of its craftsmanship and to indicate that it did not measure up to its counterpart in Tanjore.

- The Gangaikondacholapuram temple features a lower vimana, an inwardly curved shikhara, and walls that are more heavily adorned with sculptures compared to the Tanjore temple.

- The final phase of Chola temple architecture spans the 12th to 13th centuries. During this era, the gopura (entrance tower) became more prominent than the vimana (tower over the sanctum). This shift is exemplified in the Shiva temple at Chidambaram, primarily constructed during the reign of Kulottunga I (1070–1122 CE) and his successors.

Chola Metal Sculpture

The Chola period is famous for its remarkable metal sculptures, known for their aesthetic appeal and technical skill. Tanjavur was a significant center for producing these metal images.

- In North India, metal images are typically hollow, while in South India, they are solid. Both regions used the lost wax method for their creations.

- Traditionally, northern images are believed to be made from an alloy of eight metals: gold, silver, tin, lead, iron, mercury, zinc, and copper. In contrast, southern images are thought to be made from an alloy of five metals: copper, silver, gold, tin, and lead. However, analysis of actual images shows that these formulas were not always followed.

- The iconography and style of metal images in both regions were similar to those of stone images. These metal sculptures were clothed and adorned, playing a role in temple rituals and ceremonies. Many southern images were taken in processions.

- A common theme in Chola metal sculpture is Shiva as Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance. Other themes include Krishna and the Alvar and Nayanmar saints, along with a few Buddhist images.

Archaeometric Analysis of Nataraja Images

- Ancient Hindu metal images seldom bear inscriptions, leading scholars to date them in relation to stone sculptures found in temples with datable inscriptions. The earliest three-dimensional stone Nataraja figures are located in temples constructed by the Chola queen Sembiyan Mahadevi, such as the image in the mid-10th century Kailasanathaswami temple. Some scholars suggest that bronze Natarajas also originated during this period. However, Sharada Srinivasan's analysis of archaeometric, iconographic, and literary evidence indicates that bronze representations of Shiva's ananda-tandava first emerged during the Pallava period, between the 7th and mid-9th centuries.

- Dating solid metal artefacts accurately is challenging. Lead isotope ratio analysis and trace element analysis can help identify the sources of the metals, which can be combined with stylistic analysis to group similar images. Srinivasan's examination of 130 metal images revealed distinct archaeometric differences between artefacts from the Pallava and Chola periods. Based on this, she argues that two Nataraja bronzes—one from Kunniyar in Tanjavur district and another in the British Museum, often labeled as 'Chola bronzes'—were likely made during the Pallava period.

- The early Pallava bronze representations of Nataraja are metal translations of wooden images. The limbs are close set, the sash hangs downwards, and the rim of fire is elliptical. Later, in the Chola period, craftspeople recognized the greater tensile strength of metal in comparison with wood. In the Chola bronzes, the limbs, sash, and locks flare out towards a circular rim.

- According to Srinivasan, well-rounded stone Natarajas came to the fore during the reign of Sembiyan Mahadevi, several centuries after the earliest metal images of the Pallava period. This may have been due to the poor tensile strength of stone in comparison to metal, which initially made it difficult, for instance, for stone carvers to carve the raised left leg of the dancing Shiva.

- Sculptors rendered Shiva's ecstatic and powerful dance in stone and bronze, while poets described it in words of wonder. For instance, Manikkavachakar's Tiruvachakam says 'Let us praise the Dancer who in good Tillai's hall dances with fire, who sports, creating, destroying, this heaven and earth and all else.'

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|