GM Crops & Regulatory Mechanisms in India | Science & Technology for UPSC CSE PDF Download

Genetically Modified (GM) crops, engineered to incorporate desirable traits such as pest resistance or enhanced yield, have sparked intense debate in India due to their potential to address food security and agricultural challenges, juxtaposed against ecological, health, and socio-economic concerns. The Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC) is the apex body regulating GM crops in India, overseeing biosafety and environmental impacts. The controversy surrounding GM mustard (Dhara Mustard Hybrid-11 or DMH-11), approved for environmental release in 2022, exemplifies the complex interplay of science, policy, and public sentiment.

Genetically Modified Crops: Overview

Definition and Science:

GM crops are organisms whose genetic material is altered using genetic engineering to introduce traits like pest resistance, herbicide tolerance, or enhanced nutritional content. This involves inserting foreign genes, often from unrelated species (e.g., Bacillus thuringiensis in Bt crops).

Differs from gene editing (e.g., CRISPR), which modifies existing DNA without foreign gene insertion, facing fewer regulatory hurdles.

Global Context:

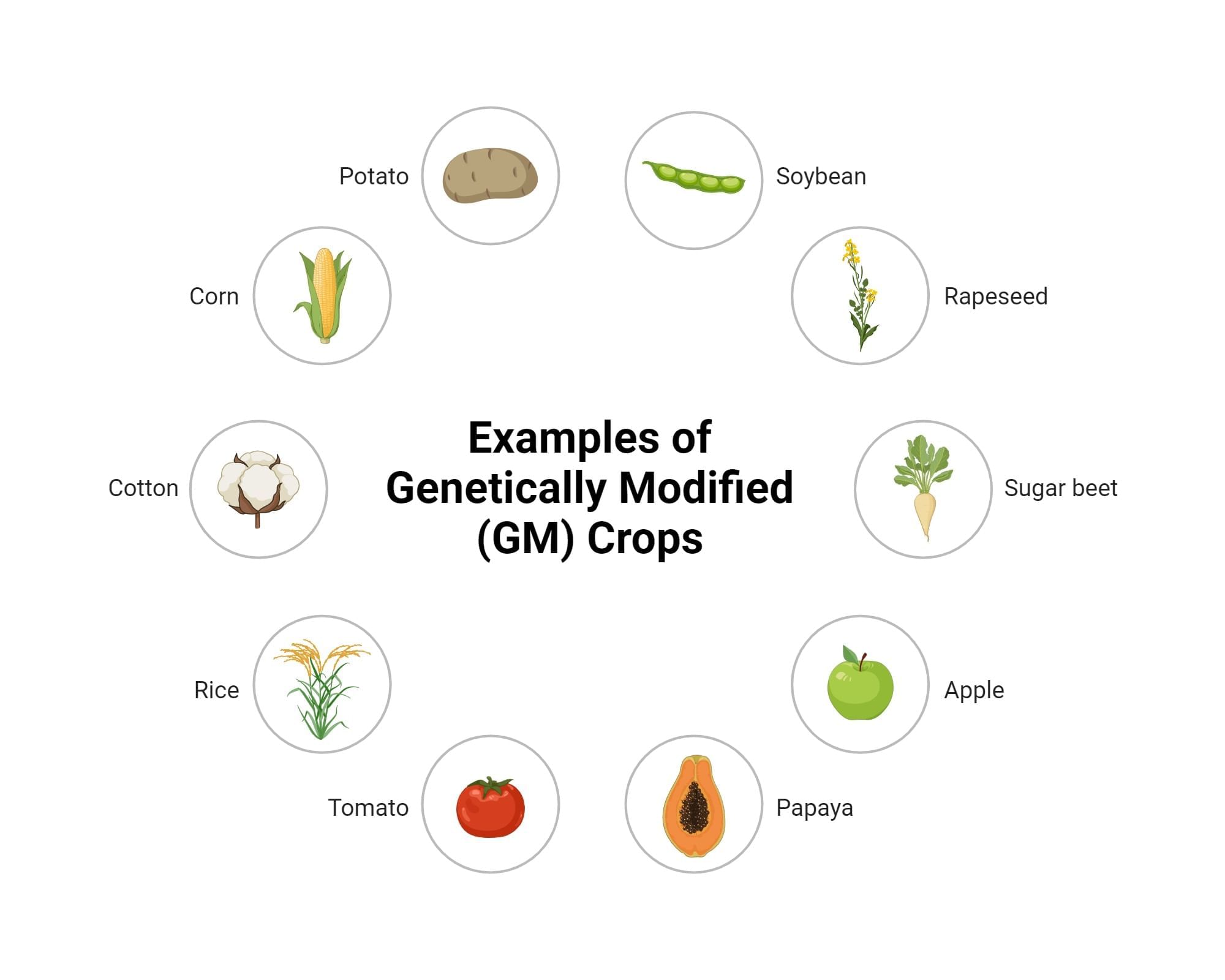

GM crops are cultivated in over 30 countries, covering 200+ million hectares by 2019, with major crops including soybean, maize, cotton, and canola. The USA, Brazil, and India (ranked fifth globally) are key producers.

Benefits include increased yields (e.g., 87% for Bt cotton in India) and reduced pesticide use; concerns involve biodiversity loss and health uncertainties.

Status in India:

Bt cotton, approved in 2002, is the only GM crop commercially cultivated in India, covering over 90% of cotton acreage and boosting India’s position as the world’s second-largest cotton producer.

Other crops like GM mustard (DMH-11) and Bt brinjal have been developed but face regulatory and legal delays.

Regulatory Mechanisms for GM Crops in India

India’s regulatory framework for GM crops is multi-tiered, governed by statutes and overseen by multiple bodies to ensure biosafety, environmental protection, and compliance with international protocols.

Key Legislation:

Environment (Protection) Act, 1986: The 1989 Rules for Manufacture, Use, Import, Export, and Storage of Hazardous Microorganisms/Genetically Engineered Organisms regulate GM activities. Violations attract penalties, including up to 5 years imprisonment and ₹1 lakh fine.

Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006: The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) oversees safety assessments of GM foods.

Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (2003): India, as a signatory, mandates public consultation and risk assessments for GMOs.

Regulatory Bodies:

Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC):

Established under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) via the 1989 Rules.

Responsibilities: Approves large-scale field trials, environmental releases, and commercialization; ensures biosafety and ecological integrity.

Criticized for reliance on foreign studies and lack of transparency in biosafety data.

Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation (RCGM):

Under the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), oversees research and small-scale trials.

Institutional Biosafety Committees (IBSC):

Institution-level bodies assess and approve initial research proposals.

FSSAI: Conducts food safety assessments for GM products.

State-Level Committees: States provide no-objection certificates for field trials, adding a layer of decentralized oversight.

Recent Regulatory Amendments:

2022 MoEFCC Exemption: Site-Directed Nuclease (SDN) 1 and 2 genome-edited crops (no foreign DNA) are exempted from the 1989 Rules, treated as conventional crops after IBSC verification, easing field trials. SDN-3 (with foreign DNA) remains under strict GMO regulations.

GEAC Expert Selection (2024): Revised rules for selecting GEAC experts to enhance scientific rigor and independence.

Supreme Court Directive (March 2025): Mandated a comprehensive national GM crop policy emphasizing public consultation, transparency, and science-based regulation.

GM Mustard (DMH-11): Development and Features

Development:

Developed by the Centre for Genetic Manipulation of Crop Plants, University of Delhi, led by Deepak Pental, using public funds.

DMH-11 is a hybrid mustard created by crossing Varuna and Early Heera-2 varieties, incorporating three genes: bar (herbicide tolerance to glufosinate), barnase (induces male sterility), and barstar (restores fertility), sourced from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens.

Objectives:

Increase yields by up to 30%, reducing India’s edible oil import dependency (₹1.56 lakh crore in 2021–22).

Facilitate hybridization in self-pollinating mustard, improving productivity and farmer incomes.

GEAC Approval:

Approved for environmental release on October 18, 2022, for seed production and testing, marking it as India’s first transgenic food crop approved for field use.

Post-approval, GEAC mandated studies on impacts on pollinators (e.g., honeybees) to address ecological concerns.

Debates Around GM Mustard

The approval of GM mustard has reignited debates, reflecting tensions between scientific innovation, environmental safety, and socio-economic implications.

Arguments in Favor:

Agricultural Productivity: Studies suggest DMH-11 increases yields by 20–30%, addressing India’s edible oil deficit and supporting food security.

Economic Benefits: Reduces farming costs through herbicide tolerance and higher yields, benefiting smallholder farmers.

Scientific Validation: Proponents, including Deepak Pental, argue that DMH-11 underwent rigorous biosafety testing, with global precedents for similar technologies.

Food Security: Aligns with India’s goal to reduce import reliance and enhance self-sufficiency in agriculture.

Arguments Against:

Environmental Risks:

Herbicide Tolerance: The bar gene may promote excessive glufosinate use, leading to herbicide-resistant “superweeds” and soil degradation.

Biodiversity Loss: Crossbreeding with wild mustard relatives could disrupt ecosystems and reduce genetic diversity.

Pollinator Impact: Concerns about effects on honeybees and other pollinators, critical for agriculture.

Health Concerns: Long-term health impacts of GM mustard consumption remain uncertain, with critics citing insufficient independent studies.

Socio-Economic Issues:

Farmer Dependency: Critics, including Kavitha Kuruganti, argue that GM seeds increase reliance on seed companies, undermining seed sovereignty.

Bt Cotton Lessons: Resistance in pests like pink bollworm, stagnant yields, and increased pesticide use raise doubts about GM mustard’s long-term viability.

Regulatory Transparency: The GEAC’s reliance on foreign studies and limited public access to biosafety data have fueled distrust.

Export Risks: GM mustard could jeopardize India’s GM-free export reputation (e.g., rice, honey), facing strict EU regulations.

Legal and Public Opposition:

Supreme Court Involvement: In 2024, the Supreme Court halted DMH-11’s rollout pending petitions from environmental groups, with hearings scheduled for 2025. It directed the government to formulate a national GM policy.

Public Protests: Activists, farmer unions, and groups like the Coalition for a GM-Free India cite ecological and health risks, demanding a ban on herbicide-tolerant crops.

2012 Technical Expert Committee (TEC): Recommended prohibiting herbicide-tolerant crops due to health and environmental risks, influencing ongoing debates.

Broader Issues in GM Crop Regulation

Regulatory Bottlenecks:

Delays in approvals (e.g., Bt brinjal moratorium since 2009) due to political caution and public opposition.

Lack of transparency in GEAC processes and insufficient public engagement, violating Cartagena Protocol commitments.

Illegal GM Cultivation: Unauthorized use of herbicide-tolerant Bt cotton in states like Maharashtra highlights regulatory gaps and farmer desperation.

Global Pressures: US pressure to import GM soy and maize conflicts with India’s biosafety stance, complicating trade negotiations.

Policy Dilemma: Balancing innovation (e.g., Jai Anusandhan’s ₹1 lakh crore RDI fund) with biosafety, biodiversity preservation, and farmer autonomy.

Recent Developments (as of 2025)

- Supreme Court Directive (2025): Ordered a science-based national GM policy, emphasizing public consultation and transparency.

- GEAC’s Ongoing Role: Continues to face scrutiny for balancing evidence and ideology, with calls for independent, depoliticized regulation.

- Public Sentiment: Social media reflects polarized views, with some advocating GM crops for productivity and others opposing them for ecological and sovereignty concerns.

- International Context: Countries like Brazil and China have embraced GM crops, while India’s cautious approach aligns with EU’s stringent regulations.

GM crops like DMH-11 offer transformative potential for India’s agriculture, addressing food security and import dependency. However, the debates around GM mustard highlight deep-rooted concerns about biosafety, biodiversity, and farmer autonomy. The GEAC, while central to regulation, faces challenges in transparency and public trust. The Supreme Court’s 2025 directive for a national GM policy provides an opportunity to craft a science-based, inclusive framework. For India, the path forward lies in balancing innovation with precaution, leveraging public-sector research, and ensuring transparent, participatory governance to align with national priorities and global commitments.

|

90 videos|491 docs|209 tests

|

FAQs on GM Crops & Regulatory Mechanisms in India - Science & Technology for UPSC CSE

| 1. What are genetically modified (GM) crops and what purpose do they serve? |  |

| 2. What are the regulatory mechanisms for GM crops in India? |  |

| 3. What are the features and potential benefits of GM Mustard (DMH-11)? |  |

| 4. What are the main debates surrounding GM Mustard in India? |  |

| 5. What broader issues are associated with the regulation of GM crops in India? |  |