Interaction and Innovation, c. 200 BCE–300 CE - 3 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

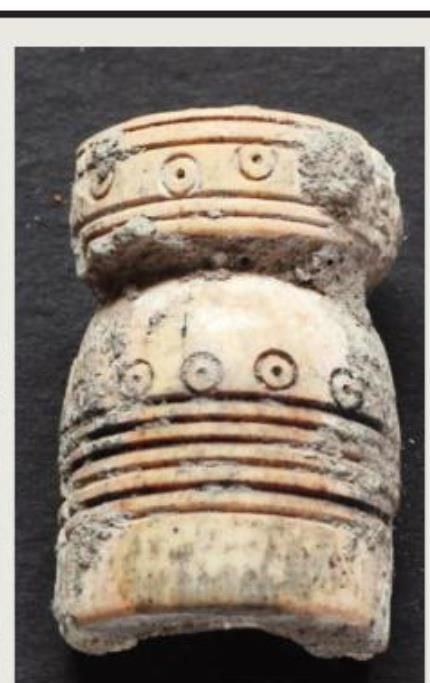

Purana Qila: Stamped and Incised Pot Sherds

Anthropomorphic Pot

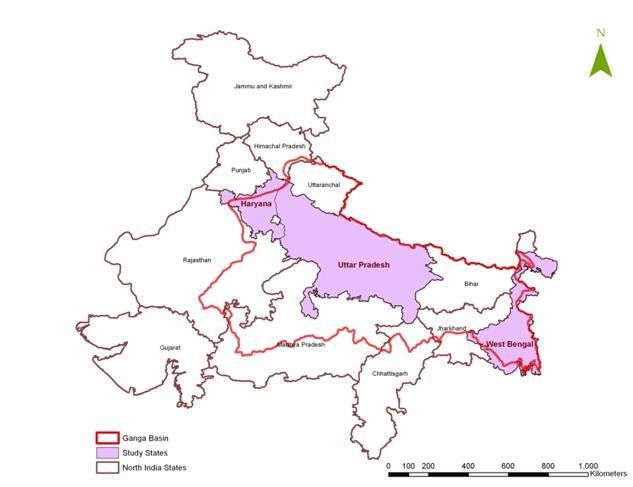

In a previous section, we discussed Erdosy’s research on settlements in the Allahabad district of Uttar Pradesh, focusing on the characteristics of Periods I and II. Now, let’s delve into Periods III and IV, which were initially dated around 350–100 BCE and 100–300 CE, respectively. However, Erdosy later revised the dates for Period III to 400–100 BCE to align better with available radiocarbon dates and other scholarly suggestions.

- During Period III, there was a continuation of the trends observed in Period II, along with some new developments. One notable change was the expansion of settlements into forested upland areas, far from the riverbanks. This period also saw the emergence of a new fifth tier of settlements, represented by four sites ranging in size from 3.46 to 5.15 hectares. A network of towns began to form, with Kaushambi as the largest site and several other towns, including Kara, Sringaverapura, Jhusi, Bhita, Reh, Lachchhagiri, and Tusaran Bihar, ranging from 19 to 50 hectares.

- Major settlements were located along rivers, approximately 31 kilometers apart, indicating a rapid expansion of both rural and urban centers with a clear settlement hierarchy. Kaushambi, in particular, developed into a major fortified city during this period, with an estimated occupied area of 150 hectares within the defense walls, supporting a population of about 24,000 people. There were also mounds marking settlements just outside the defense walls, covering an additional 50 hectares, bringing the total estimated population to around 32,000.

- In the Allahabad district, Period IV (100 BCE–300 CE) continued the fivefold settlement hierarchy and marked a peak in urban prosperity. The occupied area and population of Kaushambi expanded steadily, with around 200 hectares occupied within the fortified area, supporting a population of about 32,000 people. The defenses were strengthened, and occupation outside the walls declined, although the total occupied area grew to about 226 hectares with a population of around 36,000. Archaeological finds, such as arrowheads and skeletons from the 2nd century BCE, indicate instances of war and destruction.

- Outside the eastern gate of Kaushambi, the remains of a brick altar shaped like an eagle flying southeast, associated with animal and human bones, including a skull, were discovered. G. R. Sharma suggested that this altar was used for the purushamedha, a human sacrifice ritual. The trend of expanding settlements into upland areas continued during this period. While the population of Kaushambi grew, the Kanpur district as a whole experienced a significant slowdown in population growth, widening the gap between cities and villages.

The Middle and Lower Ganga Valley and Eastern India

Saheth-Maheth (Ancient Shravasti)

- Period II (Late Centuries CE) : This period saw the construction of a mud-and-brick rampart.

- Jetavana Monastery : Excavations at this site uncovered stupas, monasteries, and shrines dating back to the Maurya period.

- Relic Casket : One stupa contained a relic casket with bone fragments, gold leaf, and a silver punch-marked coin.

- Kushana Period Findings : A rectangular tank and a monastic complex from this period were identified.

Rajghat

- Period II (c. 200 BCE–1st centuries CE) : This period featured an earlier structural phase with a house comprising two rooms, a vestibule, a bathroom, and a well. A terracotta ring well was discovered in a later phase.

- Period III (1st to end of 3rd century CE) : This period marked the site’s most prosperous phase.

Khairadih

- Location: Sarayu River, Ballia district, eastern Uttar Pradesh.

- Findings: Remains from the early centuries CE, including a street, lanes, structures like a two-roomed house, and an underground structure.

Ganwaria (Basti District, Eastern UP)

- Periods III and IV : Attributed to the Shunga and Kushana periods, respectively.

Basarh (Ancient Vaishali, Muzaffarpur District, Bihar)

- Excavated Sections : Included fortifications.

- Period I : 2nd century BCE.

- Period II : About 1st century BCE.

- Period III : ‘Kushana–Gupta’ (3rd–4th centuries CE).

- Coronation Tank : Identified as the coronation tank of the Lichchhavis, built in the 2nd century BCE.

Katragarh (Muzaffarpur District, Bihar)

- Shunga Period Fortification : Three structural phases identified.

- Ramparts : Made of burnt brick in the first and third phases; second phase featured walls with a massive mud core and a moat.

Lauriya-Nandangarh (Champaran District, Bihar)

- Terraced Stupa : Dated between the 1st century BCE and 2nd century CE.

- Fortifications : Indications of fortifications present.

Balirajgarh (Darbhanga District, Bihar)

- Fortified Settlement : Remains of a large fortified settlement.

- Defence Wall : Made of mud-brick, dating to the 2nd century BCE.

Champa (Bhagalpur District, Bihar)

- Fortification : Strengthened by a brick wall.

- Brick Houses and Drain : Assigned to the Kushana–Gupta phase.

Patna

- Apsidal Shrine : Remains of an apsidal shrine dating to c. 100–300 CE.

- Mahasthangarh (Bogra District, Bangladesh) : A 3rd-century BCE inscription links Mahasthangarh with Pundranagara, the capital of ancient Pundravardhana. The site spans about 185 hectares and shows continuous occupation from the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) phase to the 12th/13th century CE. The early historical city featured a fortified oblong area (5000 × 4500 ft) surrounded by massive fortifications and a deep moat on three sides, with the Karatoya River bordering the western and part of the northern edge.

- Artefacts such as NBPW pottery and punch-marked and cast copper coins were found here. Chakrabarti (2006: 324) highlights the trade connections between Wari Bateshwar and Southeast Asia, suggesting that Mahasthan’s location facilitated trade routes with regions like the Barind and Bhagirathi sectors of West Bengal, the Bihar plains, Tibet, and the Brahmaputra valley of Assam. There might have been a connection between Assam and south China via Myanmar.

- Bangarh (South Dinajpur District, West Bengal) : The site along the Purnabhava River has uncovered a settlement measuring 1800 × 1000 feet, enclosed by fortifications and a moat on three sides. The five cultural phases span from the Maurya period to the medieval era, with urban prosperity noted during the c. 200 BCE–300 CE phase. Early mud fortifications were replaced by brick ramparts, and remains of houses made of burnt brick, drains, and cesspits were discovered. Bangarh is identified with Kotivarsha, a significant administrative centre.

- Tamluk (Ancient Tamralipti, Midnapur District, West Bengal) : Tamluk, located on the banks of the Rupnarayan River, was a crucial port mentioned in Indian, Graeco-Roman, and Chinese sources. Remains from Period II (3rd/2nd century BCE) and Period III (1st–2nd centuries CE) include a brick tank and terracotta ring wells. Early centuries CE artefacts consist of burnt-brick structures, rouletted ware, fine terracotta figurines, coins, seals, sealings, beads, and evidence of writing in Brahmi, Kharoshthi, and possibly a mixture of the two scripts.

- Chandraketugarh (West Bengal) : Another early historical site, details not specified in the provided content.

Red Spouted Vessel and Sprinkler from 'Kushana-Gupata' Levels, Sarnath

Chandraketugarh

- Chandraketugarh is an archaeological site located near the present-day town of Baranagar in West Bengal, India. It was a significant urban settlement during ancient times, particularly known for its trade and cultural activities. The site has yielded a wide range of artifacts, including pottery, terracotta figurines, and inscriptions, indicating its importance as a center of commerce and craftsmanship.

- The presence of various types of beads, such as sandwiched glass beads and gold-foil glass beads, suggests that Chandraketugarh was part of extensive trade networks, connecting it with distant regions like Egypt, the Mediterranean, and Rome. The site’s strategic location on the banks of the river Ganges likely facilitated its growth as a prominent urban center during the ancient period.

Central and Western India

- Rajasthan : The site of Rairh has revealed remains dating from the 3rd/2nd century BCE to the 2nd century CE and later. Excavations uncovered terracotta ring wells and walls of structures. At Sambhar, remains from the 3rd/2nd century BCE have also been discovered. Nagari has provided evidence of occupation from around 400 BCE.

- Central India : Besnagar, situated at the confluence of the Bes and Betwa rivers, was the western capital of the Shungas and a crucial trade route connecting north India with the Deccan and western ports. Excavations revealed the remains of a Vasudeva temple.

- Ujjain : Period IIIA (c. 200 BCE–500 CE) was characterized by red ware pottery and a variety of artifacts, including beads, bangles, pendants, ear ornaments, terracotta gamesmen, antimony rods, ivory combs, and clay bullae. Coins from the Kshatrapas, Kushanas, and later dynasties were found, along with a coin mold of Roman emperor Augustus Hadrianus. Evidence of bead manufacture, particularly chalcedony beads, was also present.

- Pawaya (ancient Padmavati) : Early centuries CE remains include a variety of terracottas and fine stone sculptures, such as images of the yaksha Manibhadra and a naga figure. A palm capital of the 1st century BCE associated with the deity Samkarshana has also been discovered.

Cities and Towns of the Deccan

The early historical urban phase in the Deccan region is primarily reconstructed through archaeology, as there is a lack of textual evidence. Historian Aloka Parasher argues that the Deccan is often seen merely as a bridge between North and South India, with cultural developments explained as the spread of civilizational traits from other areas.

- Overemphasis on External Influences: The impact of Maurya rule and Indo-Roman trade on urbanization in the Deccan has been overstated, while the internal processes of cultural change have not received adequate attention.

- Regional Focus: Within the Deccan, there has been a disproportionate focus on certain areas, particularly those with Ashoka’s inscriptions or Buddhist structures, neglecting other regions considered marginal.

- Sub-regions of the Deccan: The Deccan can be divided into northern, central, eastern, and southern sub-regions, each with its own cultural processes and sequences. Parasher emphasizes the differences between the southern and central Deccan, as well as among sites within these regions.

- Southern Deccan: In the southern Deccan, sites with notable neolithic–chalcolithic or early iron age megalithic occupation, such as Hallur, often lack significant early historical remains. On the other hand, several large early historical sites, like Chandravalli, Banavasi, Vadagaon-Madhavpur, and Sannati, do not have substantial prior occupation from the neolithic–chalcolithic or early iron age periods.

- Central Deccan: The central Deccan lacks direct evidence of Maurya presence, but early historical sites like Peddabankur, Kotalingala, Dhulikatta, Polakonda, and Kadambapur show evidence of pre-Satavahana period occupation, not always linked to megalithic remains.

- Kotalingala: A 50-hectare mound located at the confluence of the Paddavagu and Godavari rivers, Kotalingala featured a mud fort surrounding the settlement. Four occupational levels were identified, with the second dating to the early centuries CE. Numerous pre-Satavahana and Satavahana coins were discovered at the site.

- Dhulikatta: This 18-hectare mound on the right bank of the Hussanivagu river housed a fortified town enclosed by a mud fortification wall with gateways. A palace complex, regular residential structures, and granaries were found on the mound. A nearby Buddhist stupa, dating to the 3rd century BCE, adds to the site’s significance.

- Peddabankur: Located 10 km east of Dhulikatta, this 30-hectare unfortified mound revealed several residential structures with brick and mud-over-stone-rubble foundations. Cisterns, wells, soak pits, and drains were also discovered, along with evidence of two structural phases dating from c. 250–100 BCE and c. 50 BCE–200 CE. The site likely housed a mint, as indicated by the discovery of numerous Satavahana coins, including a gold coin of Augustus. Other significant finds included wells and the remains of a blacksmith’s workshop.

- Kondapur: An unfortified site with brick or rubble houses, Kondapur appears to have been a center for bead and terracotta production. Religious structures at the site included a stupa, vihara, and two chaityas (shrines).

Roman Coins and Iron Artefacts

- The discovery of many Roman coins and imitation bullae at various sites suggests that the Deccan economy relied heavily on trade during that period.

- Additionally, all these sites have yielded a significant number of iron artefacts and evidence of iron working, indicating the importance of iron in the local economy.

Dhulikatta: Evidence of Iron Smelting

- At Dhulikatta, archaeologists found a crucible used for iron smelting, measuring 15 cm in diameter.

- This crucible was discovered alongside charred wood, leafy material, mud, and large terracotta cakes, suggesting a connection to the iron smelting process.

Peddabankur: Blacksmith's Workshop

- Peddabankur revealed evidence of a terracotta forge, approximately 20 cm in diameter, used by blacksmiths.

- The working floor of the forge contained pieces of iron slag and finished iron artefacts, including nails, a sickle, a knife, and a ring, indicating it was a blacksmith's workshop.

Bhokardan: Ancient Bhogavardhana

- Bhokardan, located in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra, has been identified with the ancient city of Bhogavardhana.

- This city was situated on the historical route from Ujjayini to Pratishthana, and its inhabitants are mentioned in inscriptions at central Indian Buddhist sites like Sanchi and Bharhut.

Periods of Occupation

- Excavations at Bhokardan identified two periods of occupation: Period Ia, belonging to the pre-Satavahana or early Satavahana phase, and Period Ib, associated with the late Satavahana phase.

- Period II was linked to the post-Satavahana period.

Artefacts and Pottery

- The artefacts discovered at Bhokardan included punch-marked coins, Satavahana and Kshatrapa coins made of copper, and terracotta seals and sealings.

- The pottery from Period Ia included various types such as black and red burnished ware, coarse black and red ware, and crude handmade red wares.

- In contrast, Period Ib featured more refined pottery, including red-slipped ware, black burnished ware, and micaceous red-slipped ware.

Bead Industry and Crafts

- A significant number of beads made from materials like terracotta, glass, shell, and faience were found, indicating a thriving bead industry.

- Other crafts included the making of shell bangles and ivory work.

Terracotta Objects

- Hundreds of terracotta objects were unearthed, including discs, marbles, gamesmen, wheels, whorls, and figurines.

- Unique ear ornaments and pendants were also discovered, along with votive tanks and anthropomorphic pot fragments.

Metal Artefacts

- A variety of iron and copper artefacts were found, including kitchen utensils, tools, weapons, and ornaments made of copper.

- Ivory objects such as dice, bangles, and a carved mirror handle were also recovered.

Indo-Roman Contacts

- Clay bullae, amphorae fragments, and imitation red ware pieces suggested connections with Indo-Roman trade.

Plant and Animal Remains

- Analysis of plant remains revealed a variety of cereals and legumes, while bone remains included those of wild and domesticated animals, as well as human bones.

Cities of the Far South

The initial phase of urban development in South India is typically linked to the period around 300 BCE to 300 CE. However, recent findings indicate that urbanism might have started even earlier. Ancient Graeco-Roman texts refer to various towns and cities in South India, using the term emporium to describe coastal towns involved in foreign trade. In Tamil, the word pattinam means port, as exemplified by Kaverippumpattinam, also known as Puhar.

Sangam literature portrays the urban centers of early historical South India, but there is a disparity between these literary descriptions and archaeological evidence due to factors like insufficient excavations. Some sites, such as Madurai and Kanchipuram, have been continuously inhabited, making horizontal excavations challenging. Champakalakshmi (1996) provides a detailed account of the urban centers in early historical South India. Here are a few of these centers:

(a) Vanji or Kuravur/Karur

- Location and Significance: Vanji, also known as Kuravur or Karur, was the capital of the Chera dynasty and is identified with present-day Karur in the Tiruchirapalli district, situated along the Amaravati River, a tributary of the Kaveri. This site was a major political, craft, and trade center in early historical South India.

- Evidence of Trade and Crafts: Excavations at Vanji/Kuravur revealed evidence of trade and craft activities, including Black and Red Ware (BRW), Roman amphorae, and locally made rouletted ware. Roman coins, including those from the reign of Claudius, were found, indicating strong trade links with the Roman Empire.

- Chera Mint and Craft Specialization: The discovery of numerous copper coins bearing Chera symbols like the bow and arrow, along with silver portrait coins, suggests the presence of a Chera mint in Vanji. Literary sources mention jewel making as a key craft in Karur, supported by findings of intricately carved finger rings and inscriptions naming local jewelers.

- Inscriptions and Donations: Early Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions found near Karur at sites like Pugalur and Arachchalur record donations made by Chera rulers, craftspeople, and merchants, with specific references to merchants from Karur.

(b) Muchiri (Muziris)

- Role as a Major Port: Muchiri, known as Muziris in classical accounts, was the principal port in the Chera kingdom. It was a bustling hub for international trade, with ships arriving from regions like Arabia and Egypt, as noted in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.

- Historical Accounts of Trade: The Periplus details the types of goods imported to and exported from Muchiri, highlighting its significance in ancient maritime trade. Pliny the Elder, a Roman author, mentioned the challenges posed by pirates, which affected shipping practices in the region.

- Evidence of International Trade Agreements: The Vienna Papyrus, a 2nd-century document, illustrates the extent of trade connections by recording an agreement between merchants from Alexandria and Muchiri concerning the transportation of goods.

Early Historic Tamil Nadu

- Madurai: Madurai, the capital of the Pandya kingdom, is renowned in Tamil tradition as the site of the third Sangam. The Maduraikkanchi, part of the Pattuppattu, describes Madurai as a grand city with walls on three sides and the Vaigai River on the fourth. The city was known for its palace, temples, large houses, and bustling markets. It was a hub for crafts like gold ornament making, ivory work, and bangle making, as well as a center for fine cotton textiles. Traders from Madurai were famous for selling pearls and precious stones.

- Korkai: Korkai was a significant Pandya port, famous for its pearls, as noted in Sangam literature and Greek accounts. The Arthashastra also mentions the pearl fisheries of the Pandya country. Excavations in Korkai revealed evidence of early settlements, including potsherds inscribed with Brahmi letters and pearl oysters, confirming its reputation as a center for pearl fishing.

- Uraiyur: Uraiyur, the capital of the early Cholas, is identified with a site in present-day Tiruchirapalli. Sangam poems depict Uraiyur as a fortified city with impressive buildings and mention its fine textiles. Excavations at Uraiyur uncovered three phases of occupation, with pottery ranging from Black and Red Ware (BRW) to red-slipped ware. Inscriptions in Brahmi dating to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE were found, and a rectangular cistern identified as a dying vat was discovered, indicating the site’s historical significance.

Madurai in the Maduraikkanchi

The Maduraikkanchi has a detailed and poetic description of the city of Madurai. Here are some highlights from that description:

- The city walls are very tall and have strong sally-ports and gateways. These gates are old and sturdy, with carvings of the goddess Lakshmi on the doorposts.

- The doors are built robustly and are blackened from the ghee poured on them as a libation. Above the gates, there are rooms that are as high as cloud-capped hills, through which flows a stream of people, like the flow of the Vaigai River.

- The houses in Madurai have various types of rooms that seem to reach the sky, with wide windows that allow the south wind to blow through.

- The streets are wide and long, as broad as rivers, filled with crowds of people from different professions and backgrounds, creating a lively noise in the morning market.

- A loudly-beating drum, reminiscent of the roar of the wind-swept ocean, announces festivals, and when instruments are played skillfully, people dance and shout with joy in the streets where buying and selling happen from morning till evening.

- The streets are adorned with various pennons used in festivals, showcasing flags of victory with different names, awarded to chiefs who conquered forts day after day.

Kaverippumpattinam: The Premier Chola Port

- Kaverippumpattinam, also known as Pumpuhar or Puhar, was the leading port of the Chola dynasty during early historical times.

- Classical texts referred to this port as Khaberis or Camara.

- The entire Sangam collection called the Pattinappalai is dedicated to describing Kaverippumpattinam.

- The port had two bustling markets situated between two sectors of the city, which were guarded by royal officers.

- The inhabitants of Kaverippumpattinam spoke various languages, indicating its diverse population.

- Kaverippumpattinam has been identified with the present-day Kaveripattinam, a small fishing village on the Tamil Nadu coast where the Kaveri river meets the Bay of Bengal.

- Excavations at Kaveripattinam have traced its history from the 3rd century BCE to the 12th century CE, showing its development from a small village port with a simple wooden dockyard to a large and impressive port city.

- Ancient remains have also been discovered in nearby villages. For instance, at Vanagiri, there are remnants of an artificial channel that transported water from the Kaveri river into a reservoir for irrigation, likely constructed in the early centuries CE.

- Brick platforms used for landing boats were found at Kilayur, and Pallavanesvaram has a Buddhist temple and monastery dating back to around the 3rd century.

- A significant number of early medieval Chola coins found at Kaveripattinam suggests that it remained an important port in later periods as well.

Kanchi and Its Early Historical Period

Kanchi , mentioned as Kachchi (Kanchi) in the Sangam texts, later evolved into the renowned temple city and Pallava capital of Kanchipuram. Archaeological excavations in the area of the Shankara matha revealed remnants from the early historical period.

In the lower levels of Period IA, Black and Red Ware (BRW) was found, while the upper levels contained black-slipped ware, rouletted ware, conical jars, terracotta figurines, and a 2nd-century CE Satavahana coin.

Excavations near the Kamakshi temple indicated three broad periods of occupation. Period IA had BRW in the lower levels, while Period IB showed a variety of artifacts including BRW, rouletted ware, terra sigillata, beads, terracottas, and iron artefacts.

A structure identified as a Buddhist shrine was also uncovered. Roman coins have not been discovered at Kanchi itself but have been found in nearby areas.

Megalithic Sites in the Krishna and Kaveri Valleys

- The Krishna and Kaveri valleys, particularly along major trade routes, are home to numerous megalithic sites. One of the most significant sites is Kodumanal, located on the northern bank of the Noyyal river, a tributary of the Kaveri. This site is believed to be the ancient city of Kodumanal, renowned in Sangam literature for its gem and jewellery trade.

- Kodumanal dates from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE and serves as both a habitation and burial site. The area is rich in beryls, semi-precious stones, and iron ore, making it a suitable location for industrial activities. Evidence of iron and steel production, including furnaces and iron slag, has been found at the site, indicating its status as a major industrial centre.

- Artifacts such as potsherds with Tamil–Brahmi writing, gemstone cutting tools, spinning and weaving equipment, and materials for shell bangle production further highlight the site’s industrial significance.

Burials and Inscriptions at Kodumanal

- Over 150 burials have been discovered to the east and north-east of the habitation area at Kodumanal. The earlier burials involved secondary interment of disarticulated remains within a cist, while later burials were pit burials within houses, close to floor levels.

- The burials contained numerous bowls and cups with post-firing graffiti, some resembling Brahmi letters. More than 100 inscribed pottery pieces were found, predominantly in the Tamil language and Tamil–Brahmi script, with a few inscriptions in Prakrit and Brahmi.

- Palaeo-magnetic dating of the potsherds suggests a timeframe of approximately 300 BCE to 200 CE. Names of individuals, some Tamil and others Sanskritic, are inscribed on the pots, including the term nikama or nigama, referring to a guild.

- Kodumanal provides crucial evidence of the transition to the early historical phase in South India, particularly regarding the emergence of literacy and the development of craft production centres.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on Interaction and Innovation, c. 200 BCE–300 CE - 3 - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What is the significance of Purana Qila in archaeological studies? |  |

| 2. What do anthropomorphic pots from the Middle and Lower Ganga Valley represent? |  |

| 3. What are the characteristics of the red spouted vessels and sprinklers found at Sarnath? |  |

| 4. How did cities in Central and Western India contribute to cultural interactions during ancient times? |  |

| 5. What innovations emerged in the Far South of India during 200 BCE–300 CE? |  |