Landforms | Geology Optional for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Fluvial Landforms |

|

| Marine Landforms |

|

| Types of Erosion |

|

| Karst Landforms |

|

| Glacial Landforms |

|

| Periglacial Landforms |

|

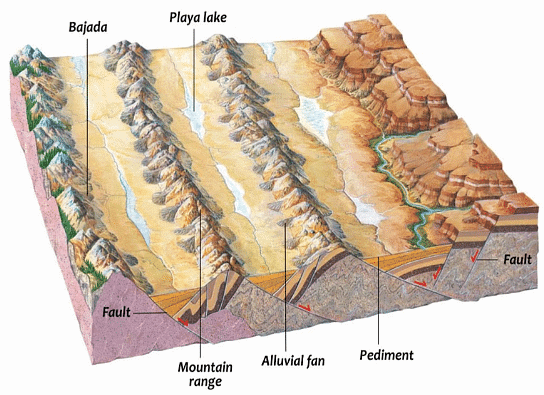

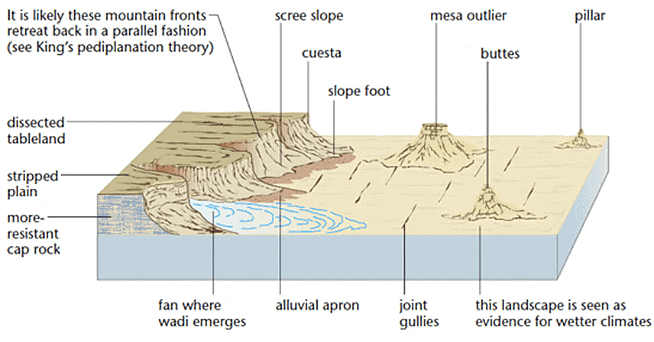

| Desert Landforms/Arid Landforms |

|

Fluvial Landforms

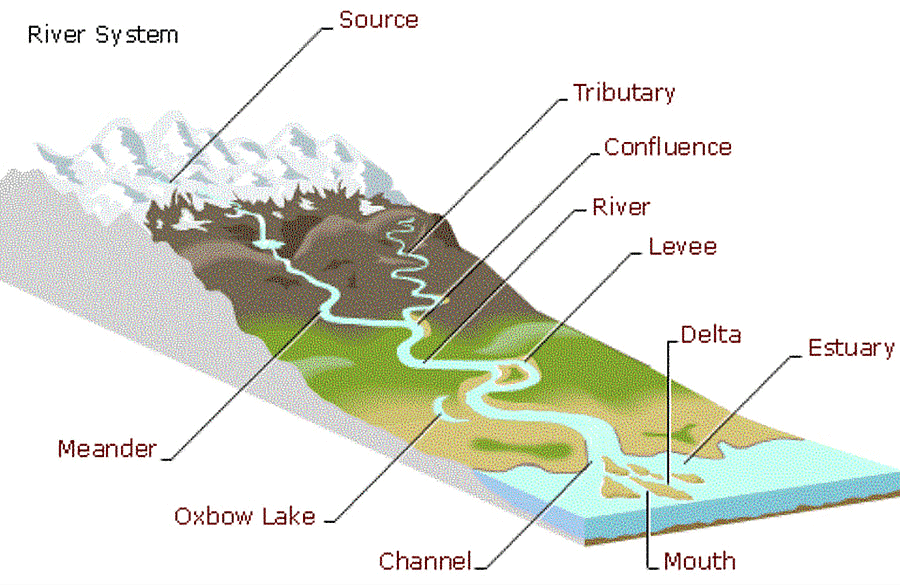

- Fluvial landforms are geological features created by the action of running water, primarily rivers. The term "fluvial" originates from the Latin word "fluvius," which means river. These landforms vary greatly in size, ranging from small features like rills to massive continental-scale units such as large rivers and their drainage basins.

- Approximately 68% of the Earth's land surface is drained by rivers flowing into the oceans. Rivers typically originate in elevated areas with a downward slope, allowing water to run off. These highland regions serve as the catchment areas for rivers, with mountain crests acting as divides or watersheds from which the streams flow.

- The initial stream, called the consequent stream, forms due to the downward slope. As this stream erodes the surface, it is joined by tributaries from either side. The drainage basin, or watershed, is a crucial component of fluvial geomorphology, encompassing the primary river and its tributaries.

Fluvial erosion occurs in various ways, including:

- Hydration: The force of running water wears down rocks.

- Corrosion/Solution: Chemical reactions cause weathering.

- Attrition: The transported material experiences wear and tear as it rolls and collides with other materials.

- Corrasion or abrasion: The solid materials carried by the river strike against rocks, wearing them down.

- Downcutting (vertical erosion): The base of a stream is eroded, leading to valley deepening.

- Lateral erosion: The walls of a stream are eroded, leading to valley widening.

- Headward erosion: Erosion at a stream's origin causes it to move backward, lengthening the stream channel.

- Hydraulic Action: River water mechanically loosens and sweeps away materials, primarily by surging into crevices and cracks in rocks and breaking them apart.

Braiding is another fluvial process where the main water channel divides into multiple, narrower channels. Braided rivers consist of a network of channels separated by small, temporary islands called braid bars. This phenomenon occurs in rivers with a low slope and/or a large sediment load.

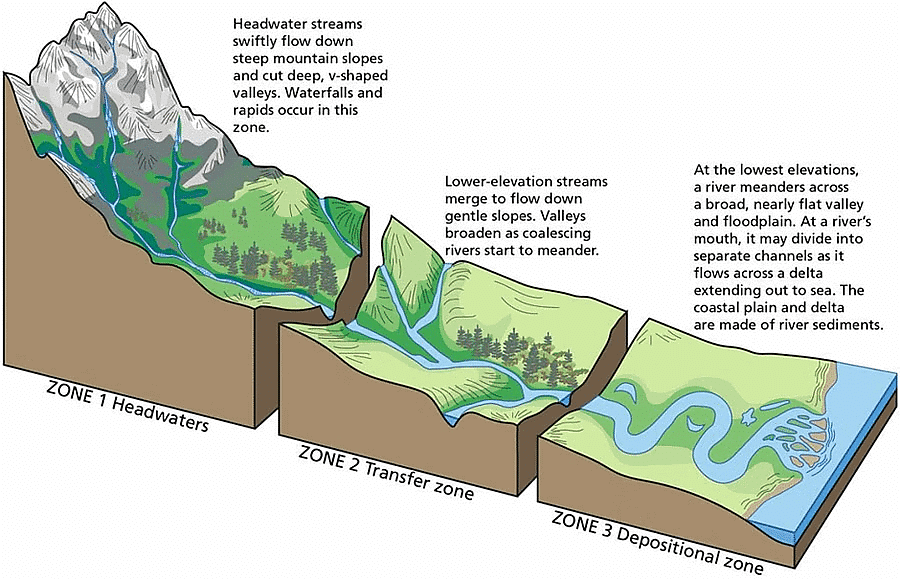

River Course

Youth

- Streams are few during this stage with poor integration and flow over original slopes

- The valley developed is thus deep, narrow and distinctly V-shaped with no floodplains or with very narrow floodplains.

- Downcutting predominates over lateral corrasion

- Streams divides are broad and flat with marshes, swamp and lakes.

- Some of the outstanding features which are developed in this stage are gorges, canyons waterfalls, rapids and river capture etc.

Mature

- During this stage, streams are plenty with good integration.

- Lateral corrasion tends to replace vertical corrasion

- The valleys are still V-shaped but wide and deep due to an active erosion of the banks;

- Trunk streams are broad enough to have wider floodplains within which streams may flow in meanders confined within the valley.

- Swamps and marshes of youth stage, as well as flat and broad inter-stream areas, disappear. The stream divides turn sharp.

- Waterfalls and rapids disappear.

- Meander and slip off slopes are the characteristic features of this stage

Old

- The river moving downstream across a broad level plain is heavy with sediments.

- Vertical corrasion almost ceases in this stage though lateral corrasion still goes on to erode its banks further

- Smaller tributaries during old age are few with gentle gradients.

- Streams meander freely over vast floodplains. Divides are broad and flat with lakes, swamps and marshes.

- Depositional features predominate in this stage

- Most of the landscape is at or slightly above sea level

- Characteristic features of this stage are floodplains, oxbow lakes, natural levees and Delta etc.

Splash Erosion

- Splash erosion or rain drop impact represents the first stage in the erosion process. Splash erosion results from the bombardment of the soil surface by rain drops.

- Rain drops behave as little bombs when falling on exposed or bare soil, displacing soil particles and destroying soil structure.

Sheet Erosion

- Sheet erosion occurs as a shallow ‘sheet’ of water flowing over the ground surface, resulting in the removal of a uniform layer of soil from the soil surface.

- Water moving fairly uniformly with a similar thickness over a surface is called sheet flow, and is the cause of sheet erosion.

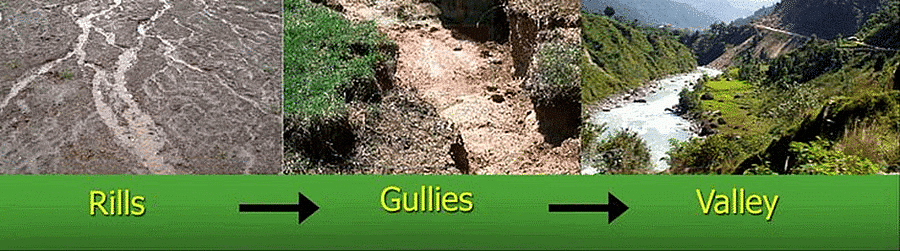

Rills, and Gully

- A rill is a shallow channel in some soil, created by the erosion of flowing water. Rills can generally be easily removed by tilling the soil. When rills get large enough that they cannot easily be removed, they’re known as gullies.

Nala or Rivulet

- A rivulet is a small stream.

Ravine

- A ravine is a landform that is narrower than a canyon and is often the product of streambank erosion.

- Ravines are typically classified as larger in scale than gullies, although smaller than valleys.

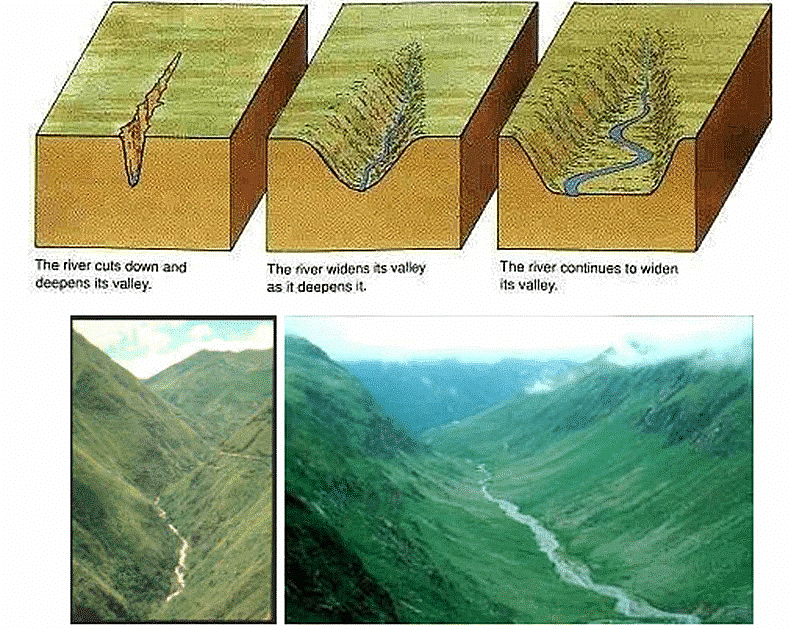

River Valleys

- The extended depression on the ground through which a stream flows throughout its course is called a river valley.

- At different stages of the erosional cycle, the valley acquires different profiles

- Valleys start as small and narrow rills

- The rills will gradually develop into long and wide gullies

- The gullies will further deepen, widen and lengthen to give rise to valleys.

- Depending upon dimensions, shape, types and structure of rocks in which they are formed, many types of valleys like the V-shaped valley, gorge, canyon, etc. can be recognised.

I-shaped valley/Gorge

- When the sides of the valley are almost parallel to each other, they form an ‘I’ shape and hence, these valleys are known as I-shaped valley.

- A gorge is a deep and narrow valley with very steep to straight sides

- A gorge is almost equal in width at its top as well as its bottom.

- Gorges are formed in hard rocks.

- Example- Indus Gorge in Kashmir

Canyon

- A canyon is a variant of the gorge.

- Unlike Gorge, a canyon is wider at its top than at its bottom.

- A canyon is characterised by steep step-like side slopes

- Canyons commonly form in horizontal bedded sedimentary rocks

- Example Grand Canyon carved by Colorado River, USA

V-shape valley

- The river is very swift as it descends the steep slope, and the predominant action of the river is vertical corrasion

- The valley developed is thus deep, narrow and distinctly V-shaped

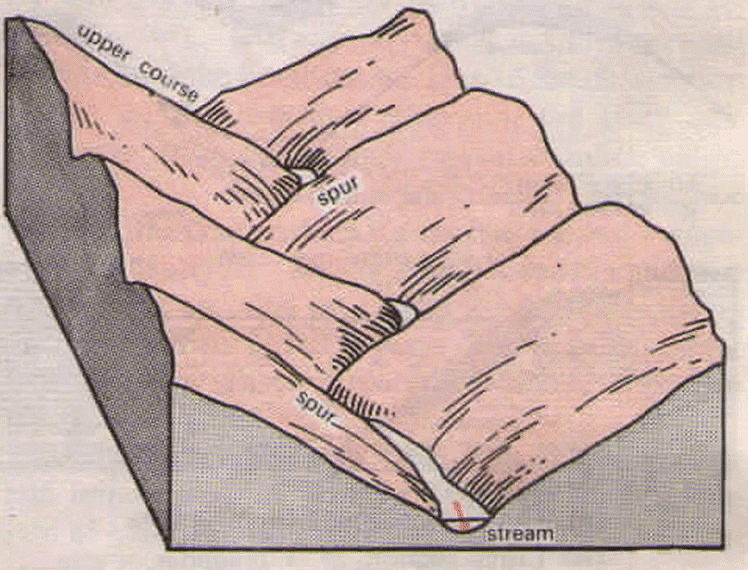

Interlocking Spurs

- Interlocking spurs are projections of high land that alternate from either side of a V-shaped valley.

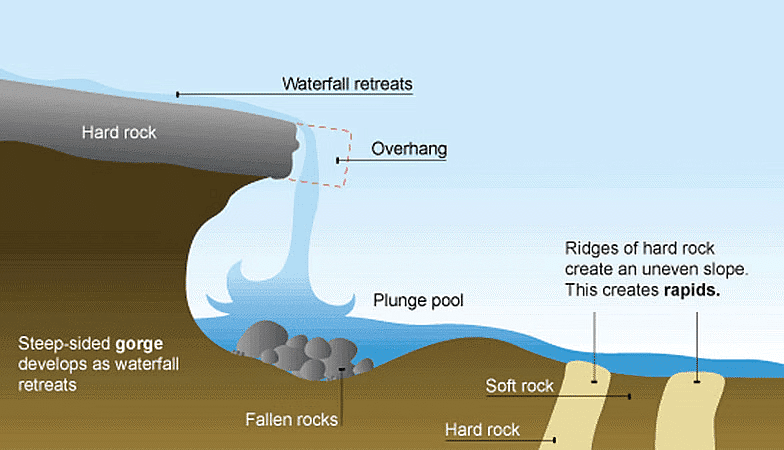

Waterfalls & Rapid

- When rivers plunge down in a sudden fall of some height, they are called waterfalls

- Their great force usually wears out a plunge pool beneath

- Waterfalls are formed because of several factors like the relative resistance of rocks lying across the river, the relative difference in topographic reliefs e.g. in Plateau etc.

- A rapid is similarly formed due to an abrupt change in gradient of a river due to variation in resistance of hard and soft rocks traversed by a river

- Waterfalls are also transitory like any other landform and will recede gradually and bring the floor of the valley above waterfalls to the level below.

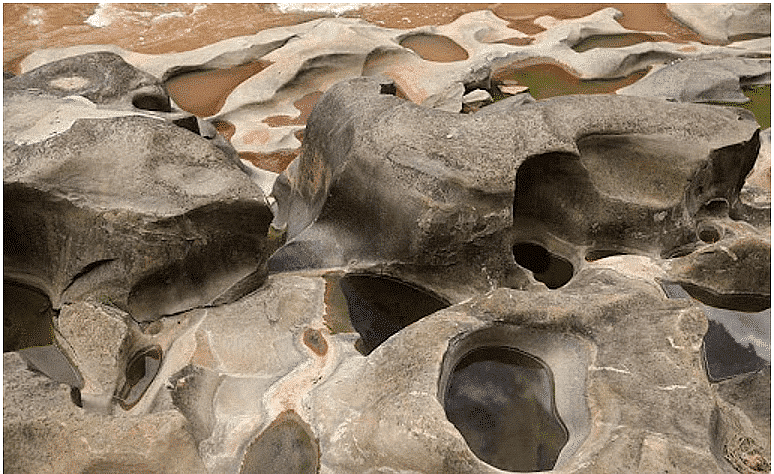

Potholes & Plunge Pool

- Potholes are more or less circular depressions formed over the rocky beds of hill-streams, because of stream erosion aided by the abrasion of rock fragments.

- Once a small and shallow depression forms, pebbles and boulders get collected in those depressions and get rotated by flowing water and consequently the depressions grow in dimensions.

- Eventually, such depressions are joined leading to deepening of the stream valley.

- At the foot of waterfalls also, large potholes, quite deep and wide, form because of the sheer impact of water and rotation of boulders. These deep and large holes at the base of waterfalls are referred to as plunge pools.

- These pools also help in the deepening of valleys

Cataract

- Cataracts are waterfalls on very large rivers.

- The term cataract is usually applied to that section of a rapidly flowing river where the running water falls suddenly in a sheer drop. When the drop is less steep, the fall is known as a cascade.

- A cataract is a powerful, even dangerous, waterfall.

Ait/Eyot

- An ait or eyot is a small island.

- It is especially used to refer to river islands found on the River Thames and its tributaries in England.

- Aits are typically formed by the deposit of sediment in the water, which accumulates over a period of time.

- An ait is characteristically long and narrow, and may become a permanent island should it become secured and protected by growing vegetation.

- However, aits may also be eroded: the resulting sediment is deposited further downstream and could result in another ait. A channel with numerous aits is called a braided channel.

Incised or Entrenched Meanders

- Incised or entrenched meanders are found cut in hard rocks. They are very deep and wide.

- In streams that flow rapidly over steep gradients, normally erosion is concentrated on the bottom of the stream channel.

- Entrenched meander normally occurs where there is a rapid cutting of the river bed such that the river does not get to erode the lateral sides.

- Meander loops are developed over original gentle surfaces in the initial stages of development of streams and the same loops get entrenched into the rocks normally due to erosion or gradual uplift of the land over which they started.

- They are widened and deepened over a long period of time and can be found as deep gorges and canyons in the areas where hard rocks are found.

- They give an indication of the status of original land surfaces over which streams have developed.

- Incised meanders are said to be an impact of river rejuvenation.

Structural Benches

- Step like sequence of geomorphic surfaces

- Differential erosion of alternately arranged hard and soft rocks forming step-like valleys known as structural benches

- The benches formed due to differential erosion of alternate bands of hard and soft rock beds are called structural benches or terraces because of lithological control in the rate of erosion and consequent development of benches.

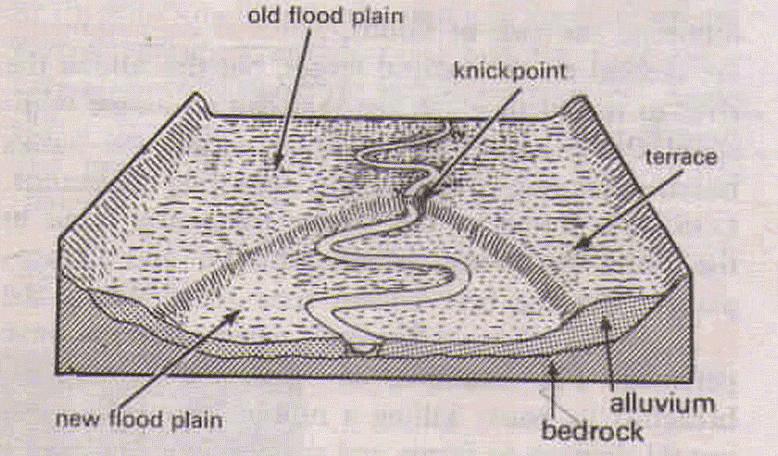

River Terraces

- River terraces refer to surfaces relating to old valley floor or floodplain levels.

- They may be bedrock surfaces without any alluvial cover or alluvial terraces consisting of stream deposits.

- River terraces are basically products of erosion as they result due to vertical erosion by the stream into its own depositional floodplain.

- There can be a number of such terraces. They are found at different heights indicating former river bed levels.

- The river terraces may occur at the same elevation on either side of the rivers in which case they are called paired terraces

Peneplain

- A peneplain (an almost plain) is a low-relief plain which is formed as a result of stream erosion

- The peneplain is meant to imply the representation of a near-final (or penultimate) stage of fluvial erosion during times of extended tectonic stability.

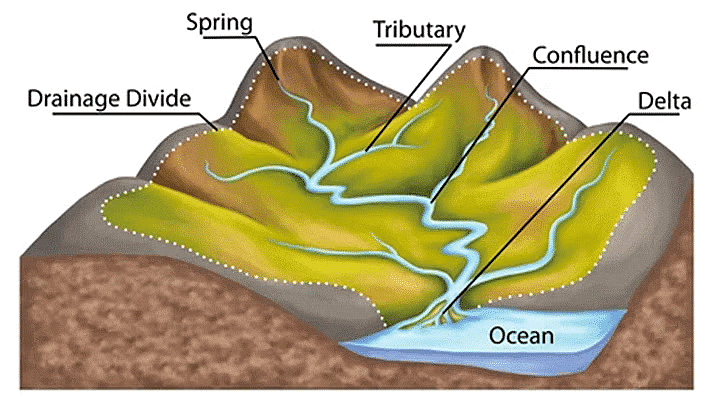

Drainage Basin

- Other terms that are used to describe drainage basins are catchment, catchment area, catchment basin, drainage area, river basin, and water basin.

- The drainage basin includes both the streams and rivers and the land surface.

- The drainage basin acts as a funnel by collecting all the water within the area covered by the basin and channelling it to a single point.

- In closed (endorheic) drainage basins the water converges to a single point inside the basin, known as a sink, which may be a permanent lake (e.g. Lake Aral, also known Aral Sea, Dead Sea), dry lake (some desert lakes like Lake Chad, Africa), or a point where surface water is lost underground (sinkholes in Karst landforms).

Drainage Divide

- Adjacent drainage basins are separated from one another by a drainage divide.

- Drainage divide is usually a ridge or a high platform.

- Drainage divide is conspicuous in case of youthful topography (Himalayas), and it is not well marked in plains and senile topography.

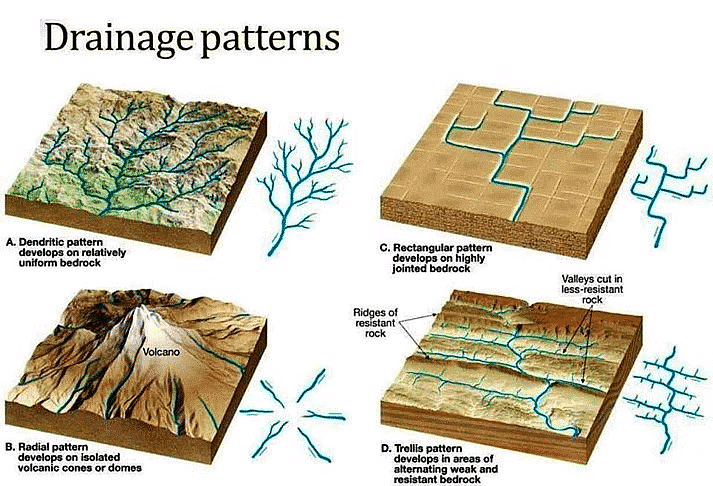

Drainage Patterns

- The drainage pattern of a stream refers to the typical shape of a river course as it completes its erosional cycle

- They are governed by the topography of the land, resistance and strength of base rocks and the gradient of the land

There are various types of drainage patterns which are described briefly as below:

Dendritic Drainage Pattern

- It is the most common form of drainage system.

- The drainage pattern resembling the branches of a tree is known as dendritic In a dendritic system, there are many contributing streams, which are then joined together into the tributaries of the main river

- The examples of Dendritic Pattern include the rivers of northern plain such Indus.

Trellis Drainage Pattern

- In the trellis drainage pattern, the primary tributaries of rivers flow parallel to each other and they are joined by secondary tributaries at the right angle.

- The geometry of a trellis drainage system is similar to that of a common garden trellis used to grow vines.

- Trellis drainage is characteristic of folded mountains,

- Examples of trellis pattern include the drainage system of the Appalachian Mountains in North America and Seine and its tributaries in Paris basin (France) etc.

Parallel Drainage Pattern

- A parallel drainage system is a pattern of rivers caused by steep slopes with some relief.

- The parallel drainage pattern is observed in a uniformly sloping region where the tributaries seem to be running parallel to each other.

- A parallel pattern sometimes indicates the presence of a major fault that cuts across an area of steeply folded bedrock.

- Examples of this system include the rivers of Lesser Himalaya

Rectangular Drainage Pattern

- Rectangular drainage develops on rocks that are of approximately uniform resistance to erosion, but which have two directions of joining at approximately right angles.

- In the rectangular drainage pattern, the mainstream curve at right angles and the tributaries join the mainstream at right angles.

- Example Colorado river the USA

Angular Drainage Pattern

- Angular drainage pattern is commonly observed in foothill regions.

- Angular drainage patterns form where bedrock joints and faults intersect at more acute angles than rectangular drainage patterns. Angles are both more and less than 90 degrees

- the mainstream is joined by the tributaries at acute angles.

Radial Drainage Pattern

- When the rivers originate from a hill and flow in all directions, the drainage pattern is known as radial .

- Volcanoes usually display excellent radial drainage. Other geological features on which radial drainage commonly develops are domes and laccoliths.

- The rivers originating from the Amarkantak range present a good example of it.

Centripetal Drainage Pattern

- When the rivers discharge their waters from all directions in a lake or depression, the pattern is known as centripetal .

- Examples – streams of Ladakh, Tibet and Loktak Lake in Manipur (India)

Annular Drainage Pattern

- In an annular drainage pattern streams follow a roughly circular or concentric path along a belt of weak rock, resembling in plan a ring-like pattern.

- Example of such system include Black Hill streams of South Dakota, USA

Fluvial Landforms – Depositional

- Fluvial Depositional landforms are made by river sediments brought down by extensive erosion in the upper course of the rivers.

- Rocks and cliffs are continually weathered and eroded in the youth stage or upper course of the river.

- The river moving downstream on a level plain brings down a heavy load of sediments from the upper course.

- The decrease in stream velocity in the lower course of the river reduces the transporting power of the streams which leads to deposition of this sediment load.

- Coarser materials are dropped first and finer silt is carried down towards the mouth of the river

- This depositional process leads to the formation of various depositional landforms through fluvial action such as Delta, Levees and Flood Plain etc.

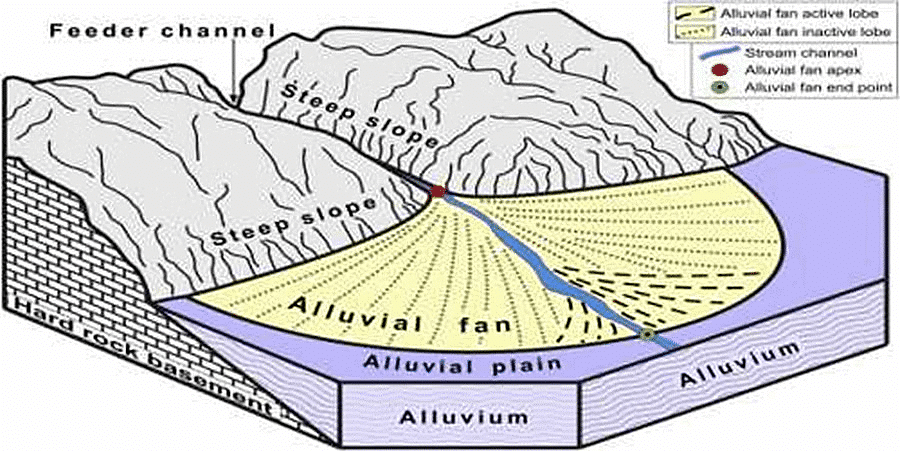

Alluvial Fans and Cones

- An alluvial fan is a cone-shaped depositional landform built up by streams, heavy with sediment load.

- Alluvial fans are formed when streams flowing from mountains break into foot slope plains of low gradient.

- Normally very coarse load is carried by streams flowing over mountain slopes. This load gets dumped as it becomes too heavy to be carried over gentler gradients by the streams

- Furthermore, this load spreads as a broad low to a high cone-shaped deposit called an alluvial fan that appears as a series of continuous fans.

- Alluvial fans in humid areas show normally low cones with a gentle slope from head to toe and they appear as high cones with a steep slope in arid and semi-arid climates.

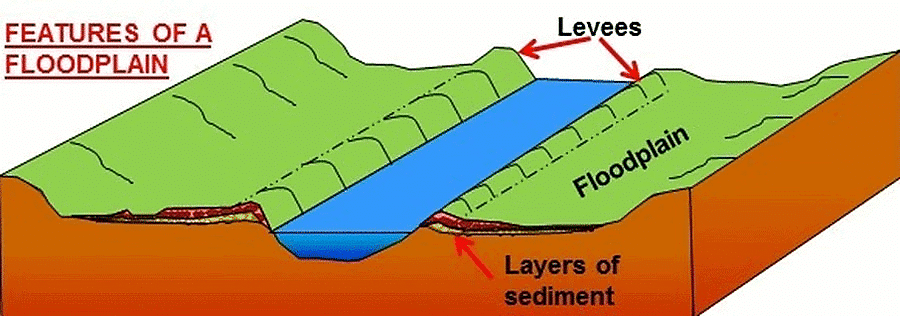

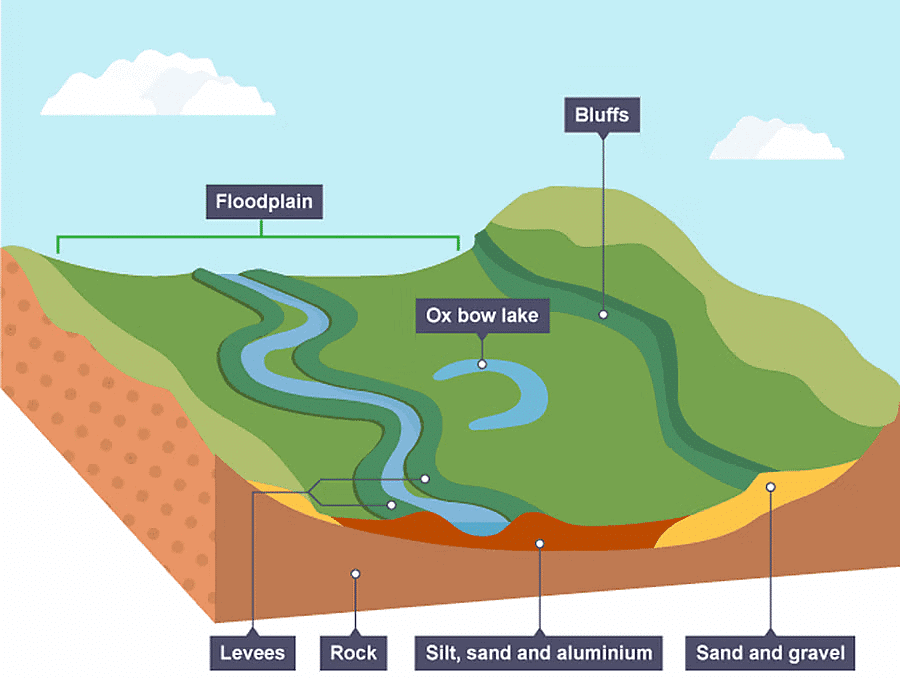

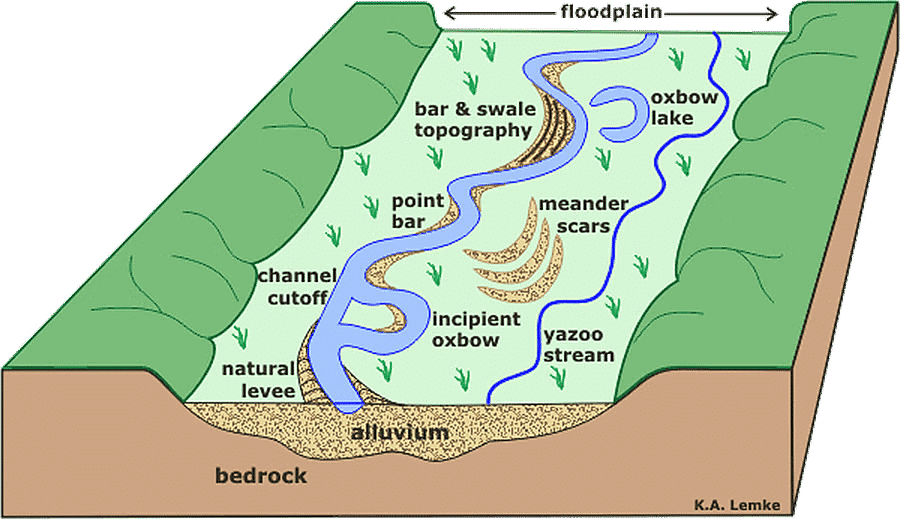

Floodplains

- Floodplain is a major landform of river deposition.

- Deposition develops a floodplain just as erosion makes valleys.

- Rivers in the lower course carry large quantities of sediments

- Large sized materials are deposited first when stream channel breaks into a gentle slope.

- Sand, silt and clay and other fine sized sediments are carried over gentler channels by relatively slow-moving waters

- During annual or sporadic floods, these materials are spread over the low lying adjacent areas. A layer of sediments is thus deposited during each flood, gradually building up a floodplain

- In plains, channels shift laterally and change their courses occasionally leaving cut-off courses which get filled up gradually by relatively coarse deposits.

- The flood deposits of spilt waters carry relatively finer materials like silt and clay.

- Active Floodplain – A riverbed made of river deposits is the active floodplain.

- Inactive Floodplain – The floodplain above the bank is an inactive floodplain. Inactive floodplain above the banks basically contains two types of deposits flood deposits and channel deposits.

- Delta plains – The floodplains in a delta are called delta plains.

Doab

- Doab is the tract of land between two converging rivers.

- Doab is a term used in South Asia particularly in India and Pakistan to refer to ” tongue” or tract of land lying between two converging rivers.

Natural Levees

- This is an important landform associated with floodplains.

- They are found along the banks of large rivers.

- They are low, linear and parallel ridges of coarse deposits along the banks of rivers on both sides due to deposition action of the stream, appearing as natural embankments.

- At the time of flooding, the water is spilt over the bank. As the speed of flow of the water comes down, large sized sediments with high specific gravity are dumped along the bank as ridges.

- They are high nearer the banks and slope gently away from the river.

- Generally, the levee deposits are coarser

- When rivers shift laterally, a series of natural levees can form.

- Artificial embankments are formed on the levees to minimize the risk of the floods.

- But sudden bursts in the banks due to the pressure of water can cause disastrous floods.

- An example of such flood can be seen in Hwang Ho river which is also called China s sorrow.

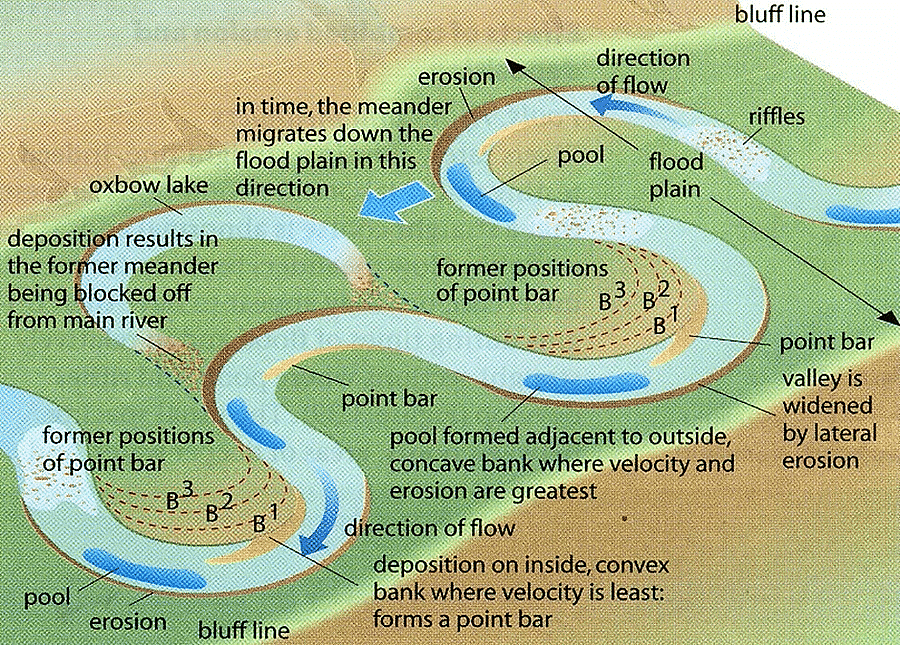

Point Bars & Cut Banks

- Point Bar is also associated with floodplain

- Point bars are also known as meander bars.

- A point bar is a depositional feature

- It is formed by alluvium that accumulates in a linear fashion on the inside bends of streams and rivers below the slip-off slope.

- They are found on the convex side of meanders of large rivers.

- They are almost uniform in profile and in width and contain mixed sizes of sediments.

- Long and narrow depressions can be found in between the point bars where there is more than one ridge

- Rivers build a series of them depending upon the water flow and supply of sediment.

- As the point bars are built by the rivers on the convex side, erosion takes place on the concave side of the bank.

- Cut banks are found on the outside of a bend in a river. Cut banks are caused by the moving water of the river wearing away the earth.

Meanders

- In large flood and delta plains, rivers rarely flow in straight courses. Loop-like channel patterns called meanders develop over flood and delta plains

- Normally, in meanders of large rivers, there is active deposition along the convex bank and undercutting along the concave bank.

- If there is no deposition and no erosion or undercutting, the tendency to meander is reduced.

- The concave bank is known as a cut-off bank which shows up as a steep scarp and the convex bank presents a long, gentle profile and is known as the slip-off bank.

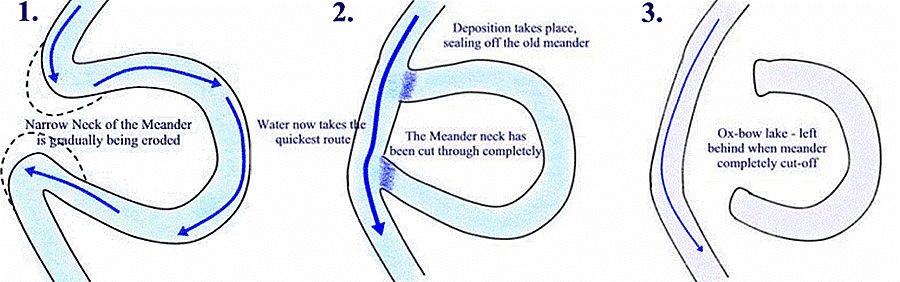

Oxbow Lake

- In the lower course of a river, meanders become very much more pronounced

- As meanders grow into deep loops, the same may get cut-off due to erosion at the inflexion points and are left as independent water bodies, known as ox-bow lakes.

- Through subsequent floods that may silt up the lake, oxbow lakes are converted into swamps in due course of time. It becomes marshy and eventually dries up

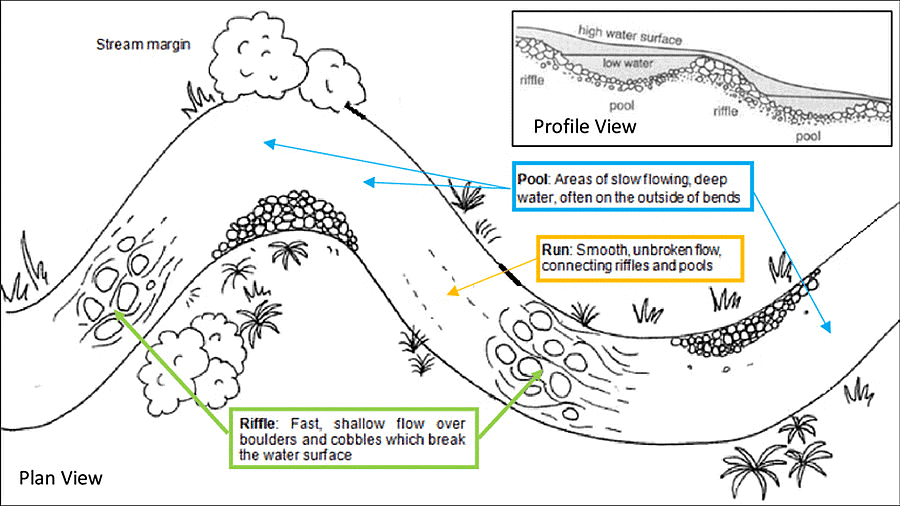

Riffle and Pool

- Pools: An area of the stream characterized by deep depths and slow current. Pools are typically created by the vertical force of water falling down over logs or boulders. The movement of the water carves a deeper indentation in the stream bed. Pools are important because they can provide depth and still water.

- Riffles: An area of stream characterized by shallow depths with fast, turbulent water. The riffles are short segments of the stream where water flow is agitated by rocks. The rocky bottom provides protection from predators, food deposition, and shelter. Riffle depths vary depending upon stream size but can be as shallow as 1 inch or deep as 1 meter. The turbulence and streamflow result in high dissolved oxygen concentration.

Bluff

- A bluff is a small, rounded cliff that usually overlooks a body of water, or where a body of water once stood.

- Bluff is a ridge of land that extends into the air.

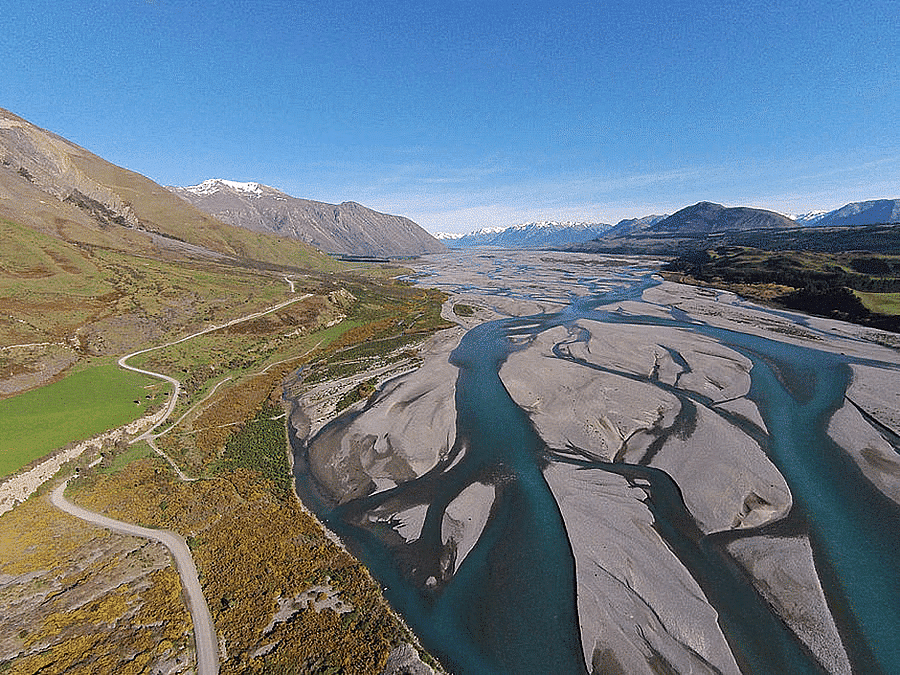

Braided Channels

- A braided channel consists of a network of river channels divided into multiple threads and separated by small and often temporary islands called eyots .

- Braided channels are commonly found where water velocity is low and the river is heavy with sediment load

- Deposition and lateral erosion of banks are essential for the formation of the braided pattern.

- There is the formation of central bars due to selective deposition of coarser material which diverts the flow towards the banks causing extensive lateral erosion

- As the valley widens due to continuous lateral erosion, the water column is reduced and more and more materials get deposited as islands and lateral bars developing a number of separate channels of water flow.

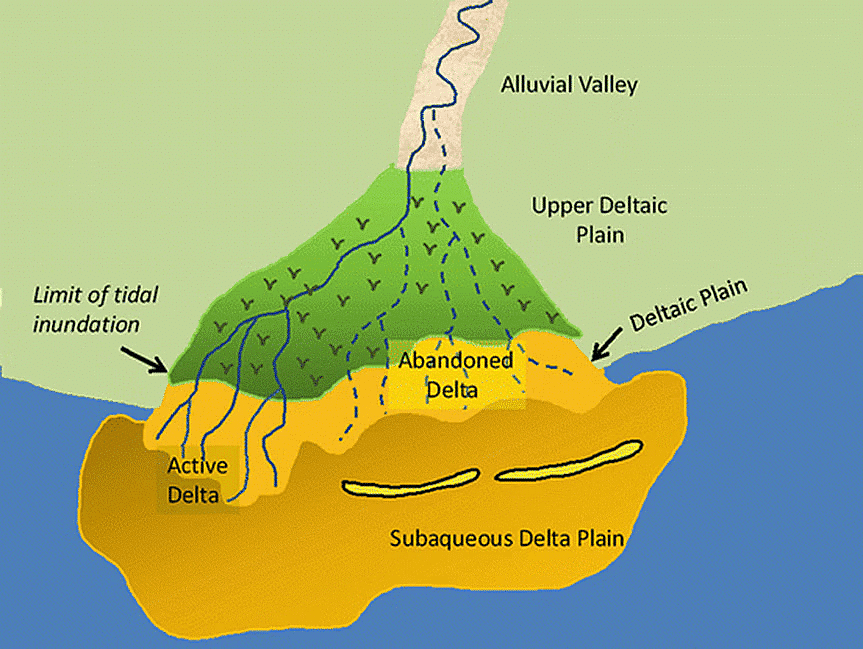

Delta

- Deltas are fan-shaped alluvial areas, resembling an alluvial fan

- This alluvial tract is, in fact, a seaward extension of the floodplain

- The load carried by the rivers is dumped and spread into the mouth of the river at sea. Further, this load spreads and piles up as a low cone

- Unlike in alluvial fans, the deposits making up deltas are very well sorted with clear stratification. The coarsest sediments are deposited first and the finer sediments are carried out further, into the sea.

- Deltas extend sideways and seaward at an amazing rate

- As the delta grows, the river distributaries continue to increase in length and Delta continues to build up into the sea.

- Some deltas are extremely large. For example, the Ganges delta is as big as the whole west of Malaysia

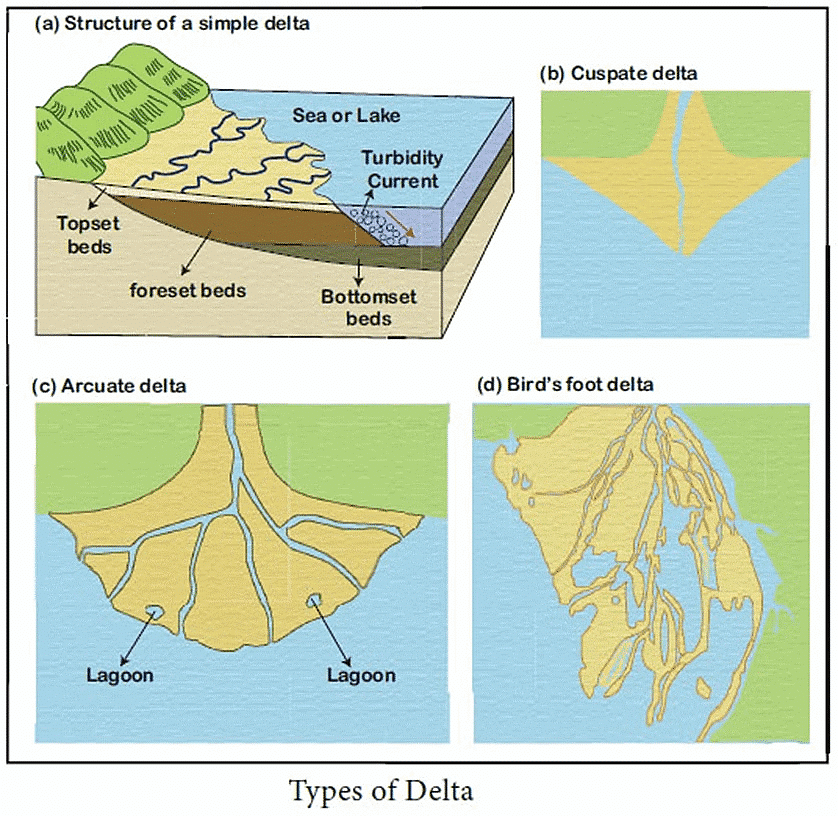

Types of Deltas: There are great variations in size, shape, growth, and importance of Deltas. A great number of factors influence the eventual formation of deltas such as depth of the river, sedimentation, sea-bed, character of tides, waves, and currents, etc. owing to these factors several types of deltas can be found.

- Bird s foot delta It s a kind of delta featuring long, stretching distributary channels, which branch outwards resembling the foot of a bird. Deltas that are less subjected to wave or tidal action culminates to a bird s foot delta. Example the Mississippi River has a bird s foot delta extending into the Gulf of Mexico

- Arcuate delta Arcuate is the most common type of delta. This is a fan-shaped delta. It s a curved or bowed delta with a convex margin facing the sea. Arcuate deltas have a smooth coastline due to the action of the waves and the way they are formed. Examples – The Nile, Ganges, and Mekong river deltas

- Cuspate delta A few rivers have tooth-like projections at their mouth, known as the cuspate delta. Cuspate deltas are formed where the river flows into a stable water body (sea or ocean). The sediments brought down by the rivers collide with the waves. As a result, Sediments are spread evenly on either side of its channel. Example Ebro river delta in Spain

- Estuarine delta some rivers have their deltas partly submerged in the coastal waters to form an estuarine delta. This may be due to a drowned valley because of a rise in sea level. Example Amazon river delta

Conditions Favorable for the Formation of Delta

- Active vertical and lateral erosion in the upper course of the river to provide extensive sediments to be eventually deposited as deltas.

- The coast should be sheltered preferable tideless.

- The sea adjoining the delta should be shallow or else the load will disappear in the deep waters.

- There should be no large lakes in the river to filter off the sediments.

- There should be no strong current running at right angles to the river mouth, washing away the sediments.

Marine Landforms

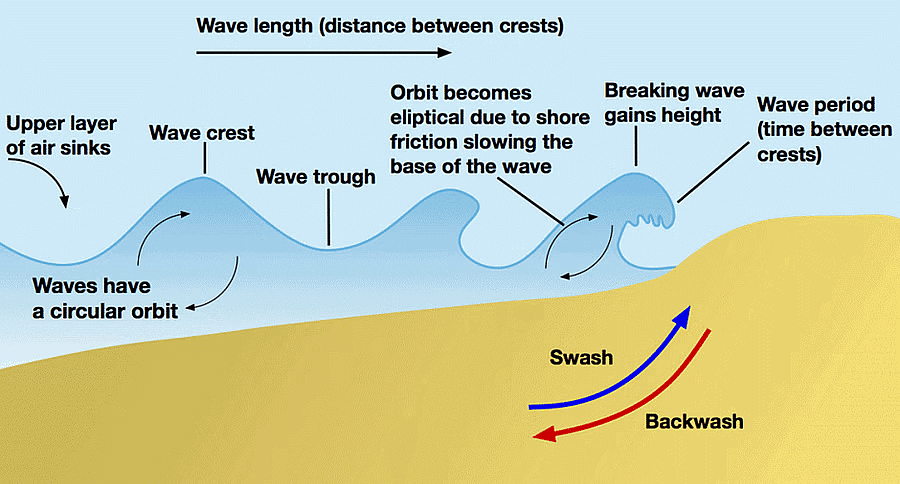

- Waves are the most potent agents of marine erosion, primarily caused by winds sweeping over the water surface, generating a series of rolling swells that move forward. As these waves approach the shallow waters near the shoreline, their speed decreases, and they become curved and refracted according to the coast's alignment.

- When the shallow water is less than the height of the waves, their forward movement is impeded, causing the wave crest to curl over and break on the shore. The water that rushes up the beach and throws rock debris against the land is known as swash, while the water that retreats or is pulled back is referred to as backwash.

- Another component of offshore drift is an undertow, a current that flows near the bottom, away from the shore. This current exerts a pulling effect that can be hazardous for those swimming in the sea.

Types of Erosion

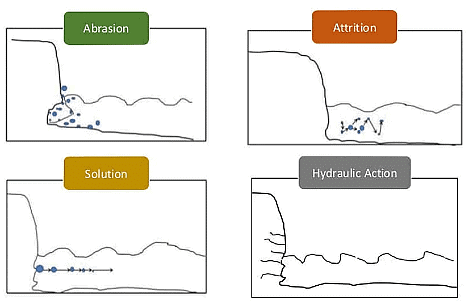

Erosion is the process of breaking down and carrying away rocks and sediments by natural forces such as wind, water, and ice. In coastal areas, several types of erosion are carried out by sea waves, winds, currents, tides, and storms. There are four main types of erosion:

- Corrasion or Abrasion: This type of erosion occurs when waves carry rock debris of various sizes and shapes, which crash against the base of cliffs and wear them down. This process, known as corrosion, helps break down the cliffs and make them more susceptible to further erosion. Incoming tides and waves then complete the process by carrying away the eroded material into the sea.

- Attrition: Attrition is the process by which waves transport beach materials such as boulders, pebbles, shingles, and fine sand, causing these materials to collide with each other and break into smaller pieces. This grinding and polishing of materials against the cliff faces and one another result in the formation of the fine sand that makes up beaches.

- Hydraulic Action: Hydraulic action refers to the erosion that takes place when the movement of water against a rock surface results in mechanical weathering. It involves the ability of moving water, such as flowing currents or waves, to dislodge and transport rock particles. Hydraulic action is different from other water-related erosion processes, like static erosion, where water dissolves salts and carries away organic material from unconsolidated sediments, or chemical erosion, which is more commonly known as chemical weathering. Hydraulic action is a mechanical process in which the water current flows against the banks and bed of a river, removing rock particles as it goes.

- Solvent Action: Solvent action is another form of erosion, though it mainly affects soluble rocks like limestone and chalk. In this process, the solvent or chemical action of seawater on calcium carbonate causes chemical changes in the rocks, leading to their disintegration. This type of erosion is most pronounced along limestone coasts, where the interaction between seawater and the calcium carbonate in the rocks leads to the breakdown and eventual erosion of the rock formations.

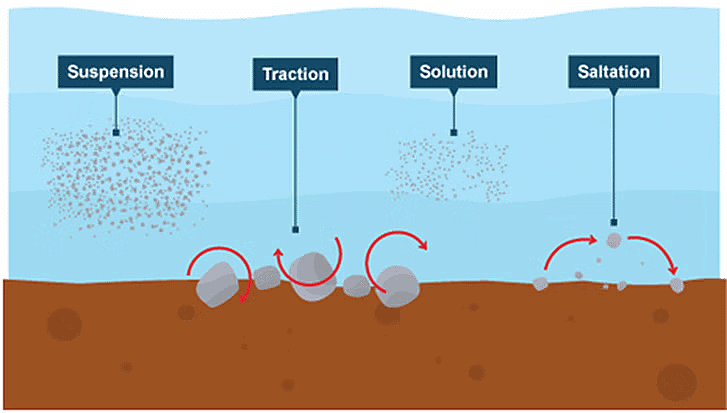

Marine Transportation

- Solution – minerals are dissolved in the water and carried along in solution.

- Suspension – fine light material is carried along in the water.

- Saltation – small pebbles and stones are bounced along the sea bed.

- Traction – large boulders and rocks are rolled along the sea bed.

Marine Landforms – Erosional

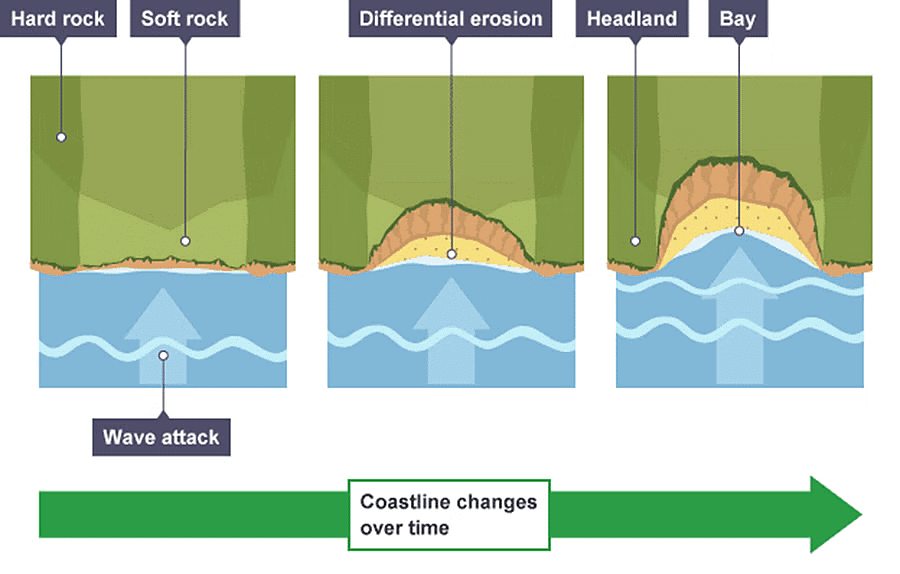

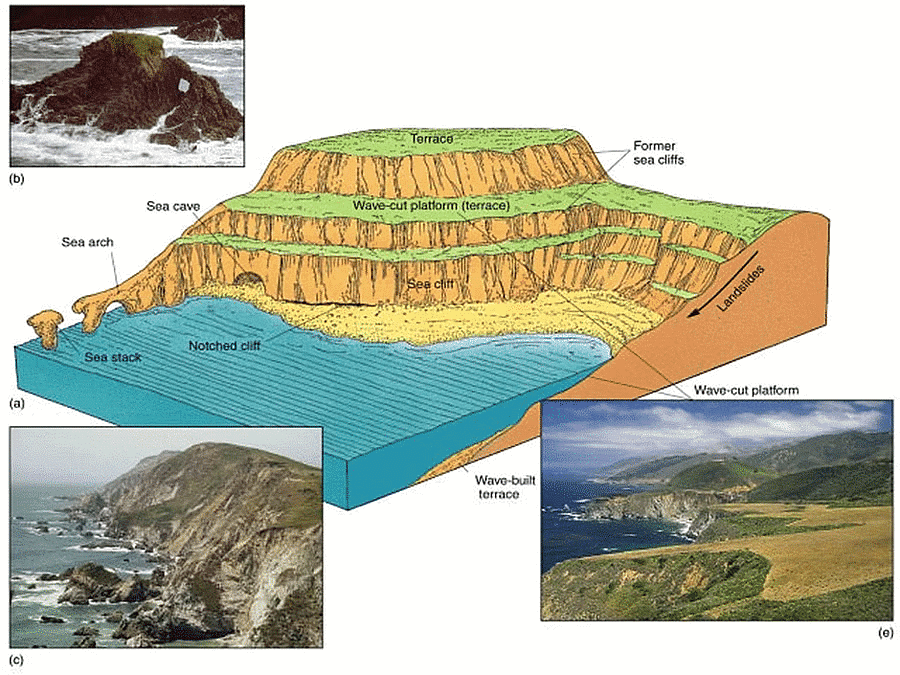

Headlands and Bays

- Coastal cliffs do not erode at a uniform rate, leading to the formation of headlands and bays when the coastline consists of varying rock types. Softer rocks like clay and sand are less resistant to erosion and tend to wear away more quickly, resulting in the creation of bays. A bay is a curved indentation in the coastline where the land slopes inward, typically featuring a beach.

- On the other hand, harder rocks such as chalk are more resistant to erosion. As the softer rocks erode, these harder rocks protrude into the sea, forming headlands. Erosional features like wave-cut platforms and cliffs are commonly found on headlands, as they are more exposed to the force of the waves. Bays tend to be more protected, with constructive waves depositing sediment to create a beach.

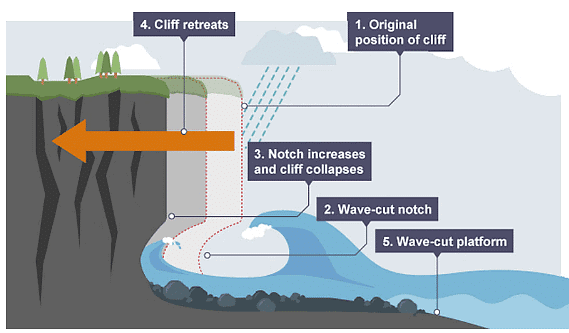

Cliffs and Wave-Cut platforms

- Cliffs are shaped through erosion and weathering. Soft rock erodes quickly and forms gentle sloping cliffs, whereas hard rock is more resistant and forms steep cliffs. A wavecut platform is a wide gently sloping surface found at the foot of a cliff.

A Wave-Cut Platform is Formed When the Following Occurs

- The ocean constantly assaults the cliff's foundation, specifically in the area between the high and low tide marks.

- A wave-cut notch, which is a small indentation in the cliff, forms as a result of erosion processes like abrasion and hydraulic action, typically occurring at high tide level.

- As this notch grows larger, the cliff's stability is compromised, leading to its eventual collapse and the retreat of the cliff face.

- The water then washes away the debris from the erosion, leaving behind a flat, wave-cut platform. This cycle continues, causing the cliff to progressively recede over time.

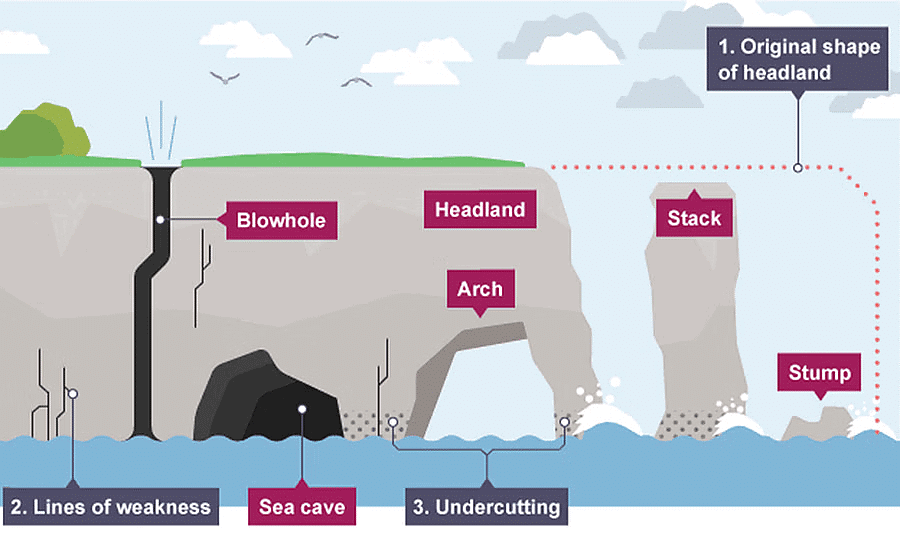

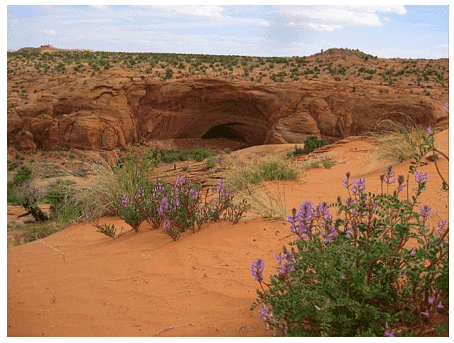

Caves, Arches, Stacks, and Stumps

- Caves, arches, stacks, and stumps are all examples of erosional features that can typically be found on a headland. These unique formations are created through a series of natural processes, mainly hydraulic action and abrasion, which help to widen existing cracks in the headland.

- Over time, waves persistently erode and grind against these cracks, causing them to expand and eventually develop into a cave. As the erosion continues and the cave grows larger, it may eventually break through the entire headland, resulting in the formation of an arch.

- The base of this arch is continually subjected to further erosion, causing it to widen until the weight of the arch's roof becomes too heavy to support itself. At this point, the roof collapses into the sea, leaving behind a stack, which is a tall, isolated column of rock.

- When a section of the sea arch collapses, the remaining vertical structure is referred to as a stack, skarry, or chimney rock. As the erosion process continues, the base of the stack is undercut, eventually causing it to collapse and form a stump.

Ria, and Cove

- A ria is a type of coastal inlet created when a river valley that has not been glaciated becomes partially submerged. This results in a drowned river valley that remains connected to the sea.

- On the other hand, a cove is a small, sheltered bay or inlet that typically has a narrow or restricted entrance. Coves can also be found at the opening of a creek or another small body of water. They are typically formed through the erosion of soft rock formations, leaving behind more durable rock that shapes a circular or oval bay with a limited entrance.

- Coves are generally smaller in size, with a width of less than 1000 feet, and can be even smaller, with some measuring less than 100 feet in diameter.

Geos and Gloups (blowholes or marine geyser)

- The intermittent splashing of waves on a cave's roof can cause the joints to expand as air is repeatedly compressed and released within them. This process can eventually create a natural shaft that might break through the surface. When waves crash into the cave, they can force water or air out of this hole, which is referred to as a Gloup or blowhole.

- As blowholes continue to enlarge and waves persistently impact the cave, the roof becomes weaker. If the roof eventually collapses, a long, narrow creek called a Geos may form.

Chasms

- These are narrow, deep indentations (a deep recess or notch on the edge or surface of something) carved due to headward erosion (downcutting) through vertical planes of weakness in the rocks by wave action.

- With time, further headward erosion is hindered by lateral erosion of chasm mouth, which itself keeps widening till a bay is formed.

Creek, and Inlet

- Creek: natural stream of water normally smaller than and often tributary to a river. creek is a narrow, sheltered waterway, especially an inlet in a shoreline or channel in a marsh.

- Inlet: An inlet is an indentation of a shoreline, usually long and narrow, such as a small bay or arm, that often leads to an enclosed body of salt water, such as a sound, bay, lagoon, or marsh.

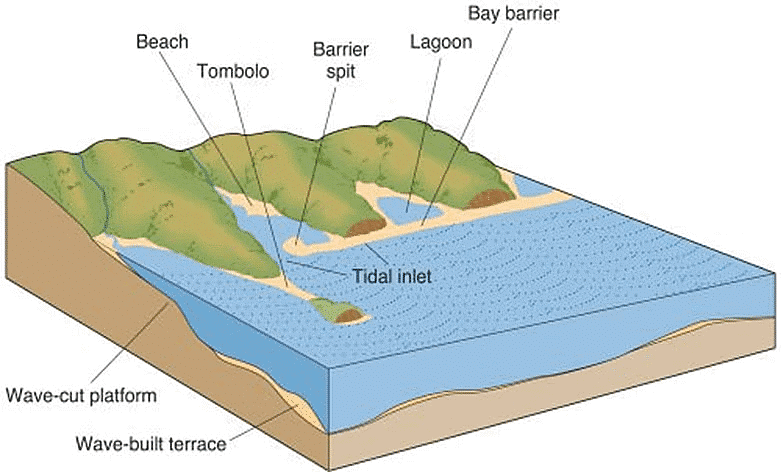

Marine Landforms – Depositional

When water loses its energy, any sediment it is carrying is deposited. The build-up of deposited sediment can form different features along the coast.

Beaches

- Beaches consist of eroded materials that have been carried from other locations and deposited by the sea. This process requires waves with limited energy, which is why beaches frequently form in sheltered areas like bays. Constructive waves, characterized by a strong swash and a weak backwash, contribute to the formation of beaches.

- Sandy beaches are commonly found in bays with shallow water and less energetic waves. In contrast, pebble beaches tend to develop in areas with cliff erosion and higher energy waves. The cross-section of a beach is referred to as the beach profile, which consists of multiple ridges called berms. These berms indicate the lines of high tide and storm tides.

- Sandy beaches usually have a gentle slope in their profile, while shingle beaches can be much steeper. At the top of the beach, the material is larger due to the high-energy storm waves carrying larger sediment. The smallest material is found closest to the water, where the waves break and gradually wear down the rock through a process called attrition.

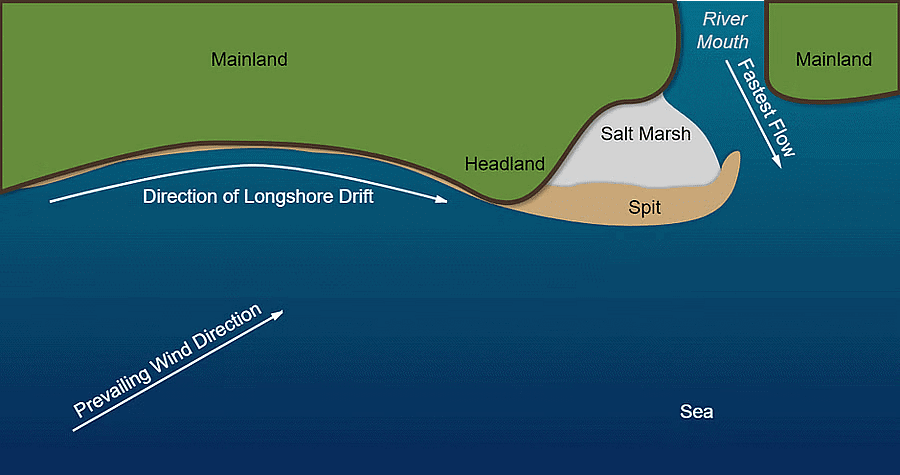

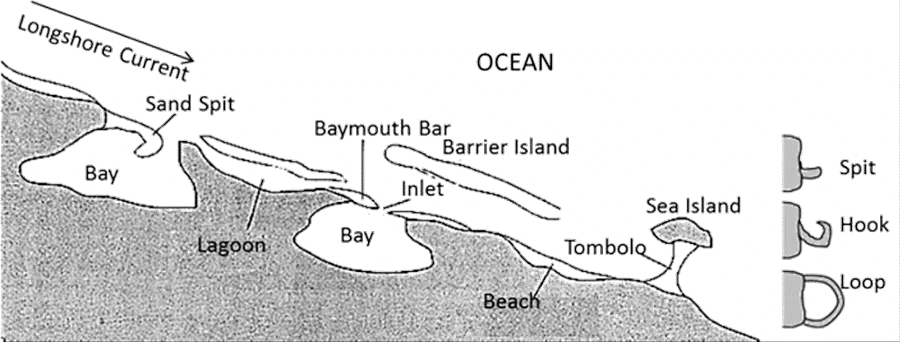

Spits and Hook

- A spit is an extended stretch of sand or shingle jutting out into the sea from the land. Spits occur when there is a change in the shape of the landscape or there is a river mouth.

- This is how spits are formed:

- Sediment is carried by longshore drift.

- When there is a change in the shape of the coastline, deposition occurs. A long thin ridge of material is deposited. This is the spit.

- A hooked end can form if there is a change in wind direction.

- Waves cannot get past a spit, therefore the water behind a spit is very sheltered. Silts are deposited here to form salt marshes or mudflats.

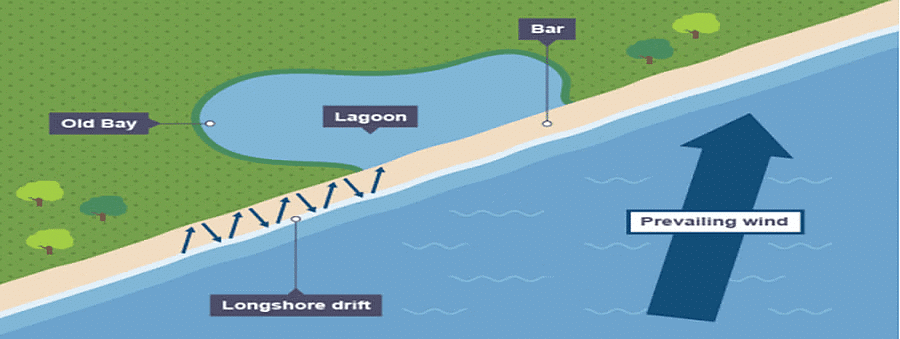

Bars, Lagoons and Barrier

- Sometimes a spit can grow across a bay and join two headlands together. This landform is known as a bar. They can trap shallow lakes behind the bar, these are known as lagoons. Lagoons do not last forever and may be filled up with sediment.

- Barrier: It is the overwater counterpart of a bar.

Tombolos & Dumb Ball

- A tombolo is a sandy isthmus. Sometimes, islands are connected with mainland by a bar called tombolo.

- If two islands are connected to each other by a bar is called Dumb Ball.

Marine Dunes & Dune Belts

- With the force of on-shore winds, a large amount of coastal sand is driven landwards forming extensive marine dunes that stretch into dune belts.

- Their advance inland may engulf farms, roads & even the entire villages;

- Hence to arrest the migration of dunes, sand binding species of grass & shrubs, such as marram grass & pines are planted.

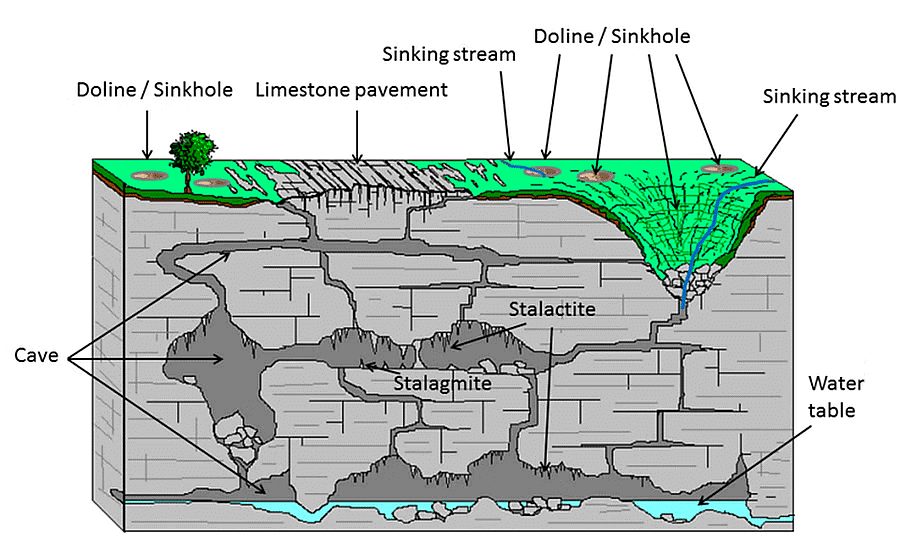

Karst Landforms

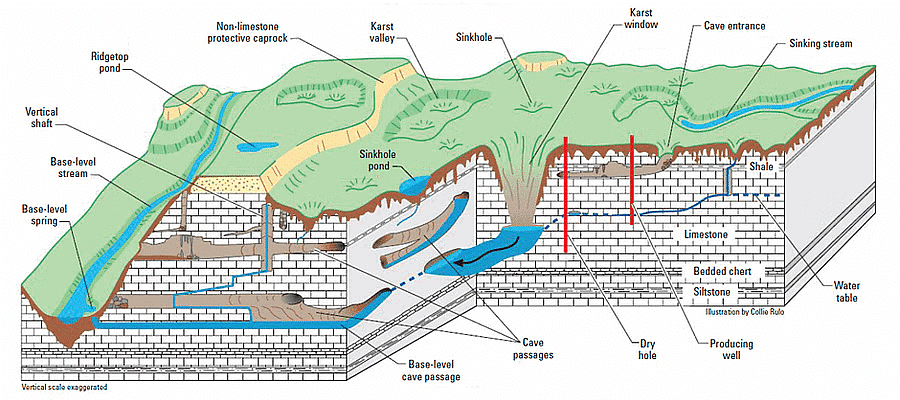

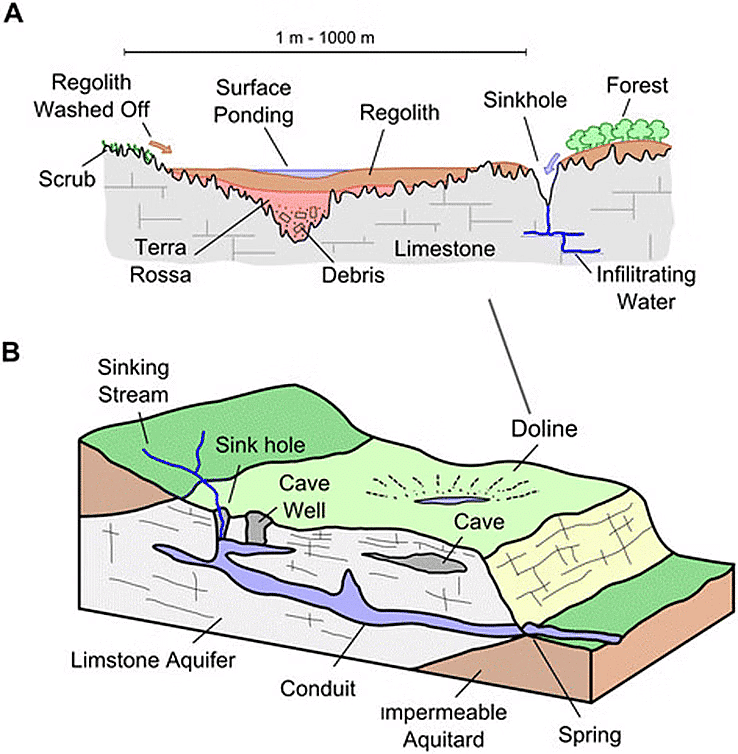

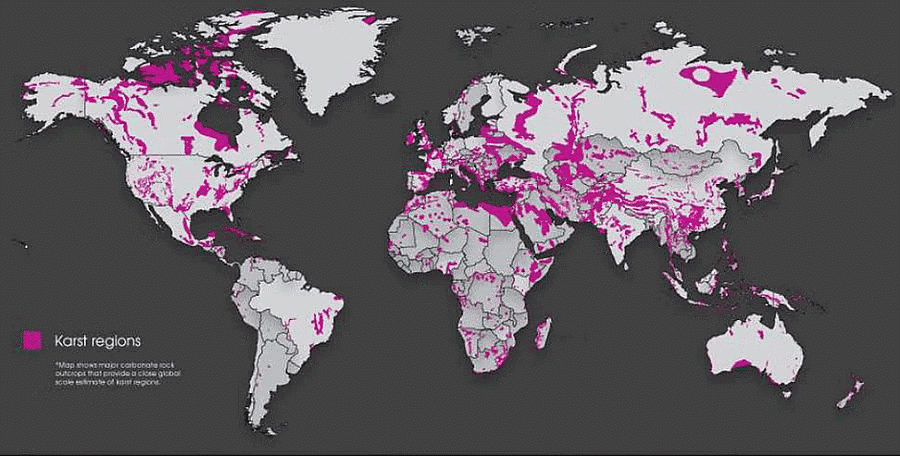

- Karst topography is a landscape formed by the dissolution of soluble rocks, such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum. This type of terrain is characterized by underground drainage systems, sinkholes, and caves. It is most prominently developed in dense carbonate rock, like limestone, which is thin-layered and highly fractured.

- Karst topography is not commonly found in chalk, as chalk is highly porous rather than dense. This means that groundwater flow is not concentrated along fractures. Karst landscapes are also more likely to develop in areas with low water tables, such as uplands with entrenched valleys, and where there is moderate to heavy rainfall. This encourages the rapid downward movement of groundwater, promoting the dissolution of bedrock. In contrast, stagnant groundwater becomes saturated with carbonate minerals, preventing further dissolution of the bedrock.

- Karst landscapes can be found in various parts of the world, including the Causses in France; the Kwangsi region of China; the Yucatán Peninsula; and the Middle West, Kentucky, and Florida in the United States. In India, karst topography is present in the Vindhya region (primarily southwestern Bihar), the Himalayas (parts of Jammu & Kashmir, Robert Cave, Sahasradhara, the eastern Himalayas, and areas near Dehradun), Pachmarhi in Madhya Pradesh, Gupt Godavari Cave in Chitrakoot (U.P.), the surrounding coast near Vishakhapatnam (Borra Caves), and Bastar in Chhattisgarh.

- Borra Caves, also known as Borra Guhalu, are situated on the East Coast of India, within the Ananthagiri hills of the Araku Valley.

Characteristics of Karst Landforms

Characteristics of Karst Landforms

- Karst regions are characterized by a stark landscape, with occasional steep slopes. These areas typically lack surface drainage, as most of the water seeps underground, leaving surface valleys dry. Streams tend to carve their paths along the joints and fissures in the rock, creating an intricate system of underground channels.

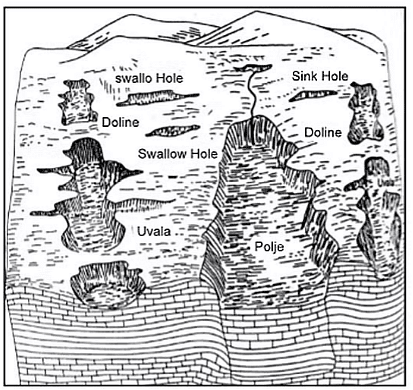

- When water reaches the base of the limestone and encounters non-porous rocks, it resurfaces as a spring or resurgence. Limestone is heavily jointed, and rainwater seeps into the rock through these joints and cracks. Over time, the process of dissolution widens these cracks, eventually forming unique features known as limestone pavements. The widened joints are referred to as grikes, while the isolated, rectangular blocks are called clints.

- Swallow holes, also known as sinkholes, are small depressions on the limestone surface, created by the dissolution process as rainwater sinks into the limestone at weak points. Water that seeps into limestone carves out caverns and passages along the joints. When multiple swallow holes merge, they form a larger hollow known as a doline. The gradual caving or subsidence of several dolines can result in an even larger depression called an uvala. In some instances, such as in Yugoslavia, large depressions called poljes may form, covering up to 100 square miles and being partially caused by faulting.

- Underground streams descending through swallow holes lead to the formation of caves and caverns, which may contain ponds or lakes. The most striking features of limestone caves are stalactites, stalagmites, and calcite pillars. Water carries dissolved calcium, and when this water evaporates, it leaves behind solidified crystalline calcium carbonate.

- Stalactites are sharp, slender, downward-growing pinnacles that hang from cave ceilings. As moisture drips from the ceiling, it flows down the stalactites and falls to the floor, depositing calcium and forming stalagmites, which are shorter, wider, and more rounded. Over an extended period, the stalactite hanging from the ceiling eventually connects with the stalagmite growing from the floor, creating a pillar.

Erosional landforms of Karst topography

Blind Valley

- A steephead valley, steephead or blind valley is a deep, narrow, flat bottomed valley with an abrupt ending.

- Karst valley abruptly terminated by the passage underground of the watercourse which has hitherto resisted the karst processes and remained at the surface.

Swallow Hole/Sinkholes/Doline

- A sinkhole, also known as a cenote, sink, sink-hole, swallet, swallow hole, or doline (the different terms for sinkholes are often used interchangeably), is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer.

- Most are caused by karst processes – for example, the chemical dissolutionof carbonate rocks or suffosion processes

- The surface streams which sink disappear underground through swallow holes.

- Local names:

- Black hole – Sea water

- Blue hole- deep under water

- Cenotes- Belize (British Honduras)

- Sotanos- Mexico

- Tomo- New Zealand

Clift

- When the Solution hole is dippen over a period of time then the dipped part is called Clift.

Pinnacles

- Vertical rock blades fretted sharped by dissolution.

Lapies/Karren

- It is formed due to differential solution activity along parallel to sub-parallel joints. They are also called grooved, fluted and ridge-like features in an open limestone field.

- The most widespread surface karst landforms are small solution pits, grooves and runnels, collectively called Karren.

Limestone Pavements

- It is a smoother form of lapies.

Sinking Creeks/Bogas

- In a valley, the water often gets lost through cracks and fissures in the bed. These are called sinking creeks, and if their tops are open, they are called bogas.

Karst Window/Fenster

- Karst fenster is a geomorphic feature formed from the dissolution of carbonate bedrock.

- In this feature, a spring emerges, then the discharge abruptly disappears into a sinkhole.

- A karst fenster is caused by a caving in of portions of the roof of a subterranean stream, thus making some of the underground stream visible from the surface.

- When a number of adjoining sink holes collapse, they form an open, broad area called a karst window.

Uvalas

- Karst depressions that are much larger than sinkholes and that display gentler slopes and more complex three-dimensional shapes are known as uvalas.

- Uvalas is collection of multiple smaller individual sinkholes that coalesce into a compound sinkhole.

- A single uvala typically contains numerous sinkholes within it.

Polje

- A polje, also karst polje or karst field, is a large flat plain found in karstic geological regions of the world, with areas usually 5 to 400 km2.

Pools

- An opening at the top with water collected in the void of the surface with varying depth

Caves/Cavern

- This is an underground cave formed by water action by various methods in a limestone or chalk area.

- Cave formation is prominent in areas where there are alternating beds of rocks (shales, sandstones, quartzites) with limestones or dolomites in between or in areas where limestones are dense, massive and occurring as thick beds

Karst Lake

- Karst lakes are formed as the result of a collapse of subterranean caves, especially in water soluble rocks.

- such as limestone, gypsum, and dolomite.

- This process is known as karstification. They can cover areas of several 100 square kilometers.

- Their shallow lakebed is usually an insoluble layer of sediment so that water is impounded, leading to the formation of lakes. Many karst lakes only exist periodically but return regularly after heavy rainfall.

Depositional landforms of Karst topography

Stalactites & Helictite

- The water containing limestone in solution, seeps through the roof in the form of a continuous chain of drops.

- A portion of the roof hangs on the roof and on evaporation of water, a small deposit of limestone is left behind contributing to the formation of a stalactite, growing downwards from the roof.

- Usually, the base is broader than the free end of the hanging stalactites.

- The ones that descend vertically are known as stalactites, whereas the ones that extend horizontally or diagonally are known as helictites.

Stalagmites & Halagmite

- A stalagmite is a type of rock formation that rises from the floor of a cave due to the accumulation of material deposited on the floor from the ceiling drippings.

- It is an upward-growing mound of mineral deposits that have precipitated from water dripping onto the floor of a cave.

- Ones that extend horizontally or diagonally from stalagmites are known as Halagmite.

Cave Pillars

- The combination or fusion of stalactites and stalagmites form the pillars

- The diameters of pillars vary

Drapes/Curtain

- Numerous needle-shaped dripstones hanging from the cave ceiling are called Drapes or Curtains.

Tufa

- Tufa is a variety of limestone formed when carbonate minerals precipitate out of ambient temperature water.

- Geothermally heated hot springs sometimes produce similar (but less porous) carbonate deposits, which are known as travertine.

Travertine

- Travertine is a sedimentary rock formed by the chemical precipitation of calcium carbonate minerals from freshwater, typically in springs, rivers, and lakes that is, from surface and ground waters.

- Developed form of Tufa is Travertine.

Drip Stone

- Calcium carbonate rock deposited in caves by the precipitation of calcite from water as excess dissolved carbon dioxide is diffused into the atmosphere.

- Dripstone takes various forms, including stalactites, helictites (having spiral form), curtains, ribbons, and stalagmites.

Terra Rossa

- Terra Rossa is a well-drained, reddish, clayey to silty clayey soil with neutral pH conditions.

Human Activities of Karst Region

- Karst regions are often barren & at best carry a thin layer of soil.

- The porosity of the rocks & the absence of surface drainage make vegetative growth difficult, hence limestone can usually support only poor grass.

- Limestone vegetation in tropical regions is luxuriant because of heavy rainfall all the year around.

- The only mineral found in association of limestones is lead.

- Good quality limestone is used as building materials & quarried for cement industry.

Glacial Landforms

Glaciers

- A glacier is a huge mass of ice that moves slowly over land. The term “glacier” comes from the French word glace (glah-SAY), which means ice. Glaciers are often called “rivers of ice.”

- Glaciers normally assume the shape of a tongue, broadest at the source & becoming narrower downhill.

- Though glacier is not liquid, but it moves gradually under the continual pressure from the snow accumulated above.

- The rate of movement is greatest in the middle where there is little obstruction.

- The sides & bottom are held back by the frictions due to valley sides & valley floors.

- If a row of stakes is planted across a glacier in a straight line, they will eventually take a curved shape down the valley, showing that the glacier moves faster at the center than at the sides.

- Glacial Landforms can be found in locations that currently have no active glaciers or glaciation processes.

- Glaciers fall into two groups: alpine glaciers and ice sheets

- Alpine glaciers

- Alpine glaciers form on mountainsides and move downward through valleys.

- Sometimes, alpine glaciers create or deepen valleys by pushing dirt, soil, and other materials out of their way.

- Alpine glaciers are found in high mountains of every continent except Australia (although there are many in New Zealand).

- The Gorner Glacier in Switzerland and the Furtwangler Glacier in Tanzania are both typical alpine glaciers.

- Alpine glaciers are also called valley glaciers or mountain glaciers.

- Ice sheets

- Ice sheets, unlike alpine glaciers, are not limited to mountainous areas. They form broad domes and spread out from their centers in all directions.

- As ice sheets spread, they cover everything around them with a thick blanket of ice, including valleys, plains, and even entire mountains.

- The largest ice sheets, called continental glaciers, spread over vast areas. Today, continental glaciers cover most of Antarctica and the island of Greenland.

- Massive ice sheets covered much of North America and Europe during the Pleistocene time period. This was the last glacial period, also known as the Ice Age. Ice sheets reached their greatest size about 18,000 years ago. As the ancient glaciers spread, they carved and changed the Earth’s surface, creating many of the landscapes that exist today.

- During the Pleistocene Ice Age, nearly one-third of the Earth’s land was covered by glaciers. Today, about one-tenth of the Earth’s land is covered by glacial ice.

The Ice-Age and Ice Masses

- An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth’s surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers.

- Earth’s climate alternates between ice ages and greenhouse periods, during which there are no glaciers on the planet.

- Earth is currently in the Quaternary glaciation.

- Today, only 2 major ice caps are present in this world – Antarctica & Greenland, along with many highlands above the snowline surviving in the world.

- Ice from the ice cap creeps out in all directions to escape as glaciers.

- When the ice sheets reaches down to the sea they float as ice shelves in polar waters.

- When ice sheets break into individual blocks, these are called icebergs.

- While afloat in the sea, only 1/9th of the iceberg’s mass is visible above the surface.

- They diminish in size when reaching warm waters & eventually melted, dropping the rock debris that was frozen inside them on the sea bed.

- Permanent snowfield is sustained by heavy snowfall in winters & ineffective snow melting & evaporation in summers as part of snow that melt during the day is refrozen during the night.

- This refreezing process repeats until it forms a hard, granular substance known as neve or firn.

- Owing to the gravitational forces, neve of the upland snowfield is drawn towards the valley below, which marks the beginning of the flow of glacier (river of ice).

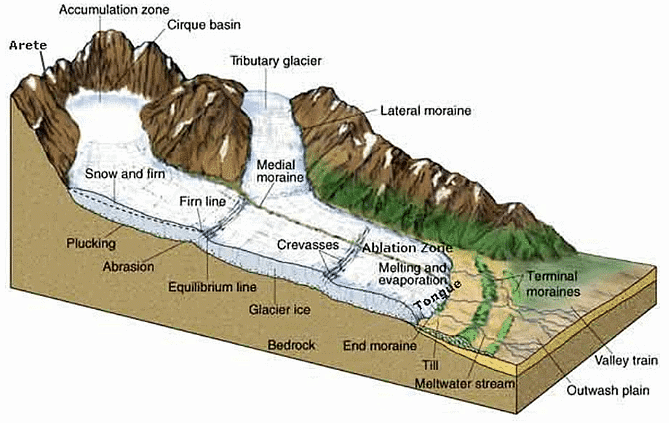

Glacial Cycle of Erosion

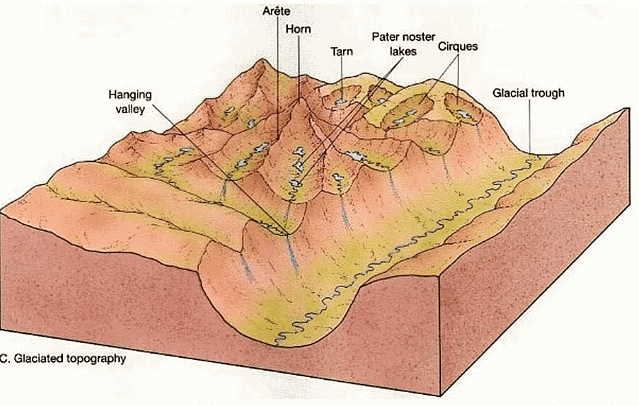

- Youth: The stage is marked by the inward cutting activity of ice in a cirque. Aretes and horns are emerging. The hanging valleys are not prominent at this stage.

- Maturity: The valley glacier gets transformed into a trunk glacier and hanging valleys start emerging. The opposite cirques come closer and the glacial trough acquires a stepped profile that is regular and graded.

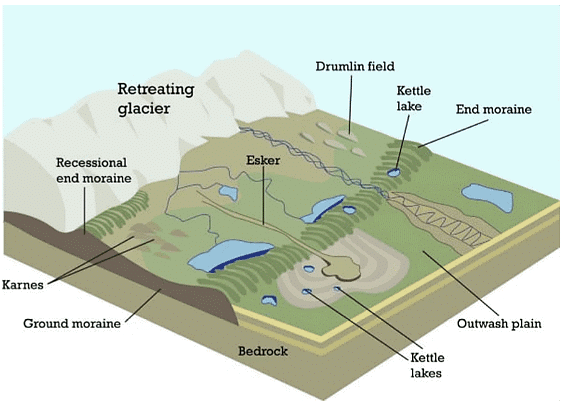

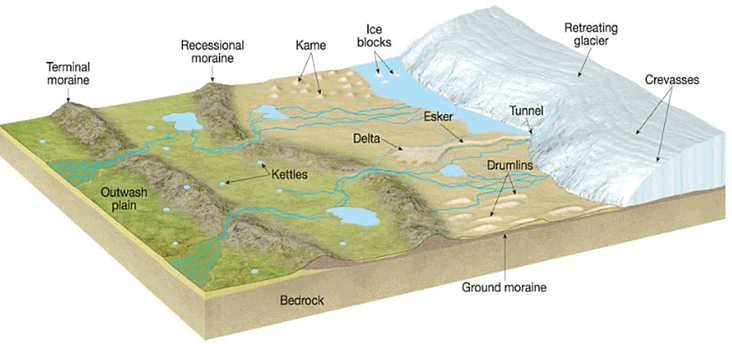

- Old Age: The emergence of a ‘U’-shaped valley marks the beginning of old age. An outwash plain with features such as eskers, kame terraces, drumlins, kettle holes, etc. is a prominent development. The opposite cirques coalesce and the summit heights are greatly reduced. Mountain tops become rounded.

Glacial Landforms

- Glaciations generally gives rise to erosional features in the highlands & depositional features on lowlands.

- It erodes its valley by two processes viz. plucking & abrasion.

- Plucking: Glacier freezes the joints & beds of underlying rocks, tears out individual blocks & drags them away.

- Abrasion: Glacier scratches, scrapes, polishes & scours the valley floor with the debris frozen into it.

Glacial Landforms – Erosional

Snout or Glacier Terminus

- A glacier terminus, toe, or snout, is the end of a glacier at any given point in time.

- The terminus is the usually the lowest end of glacier.

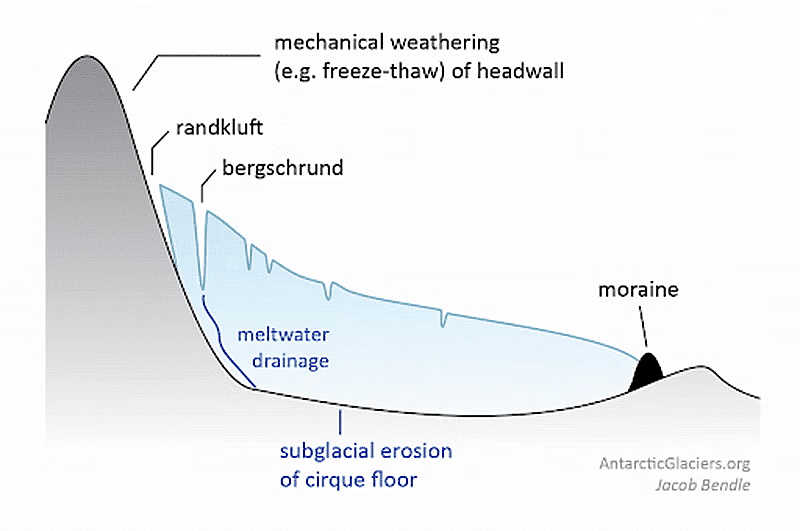

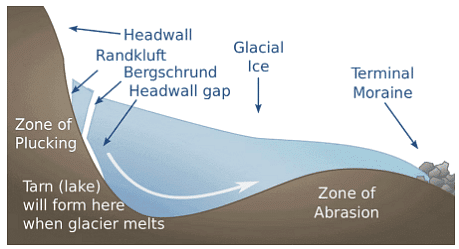

Corrie, Cirque or cwm

- The downslope movement of a glacier from its snow-covered valley head & the the intensive shattering of the upland slopes, tend to produce a depression where neve or firn accumulates.

- Plucking & abrasion further deepen the depression into a steep horse shoe-shaped basin called Cirque (in French), cwm (in wales) & Corrie (in Scotland)

- There is a rocky ridge at the exit of the corrie & when the ice eventually melts, water collect behind this barrier known as Corrie Lake or tarn.

Cols

- Cols form when two cirque basins on opposite sides of the mountain erode the arête dividing them.

- Cols create saddles or passes over the mountain.

Horns

- Horns are a single pyramidal peak formed when the summit is eroded by cirque basins on all sides.

Aretes and Pyramidal Peaks

- When two corries cut back on opposite sides of the mountain, knife edged ridges are formed called arêtes

- When three or more cirques cut back together, recession will form an angular horn or pyramidal peak.

Bergschrund

- At the head of a glacier, where it begins to leave the snowfield of a corrie, a deep vertical crack opens up called a Bergschrund or Rimaye

- This happens in summer when although the ice continues to move out of the corrie, there is no new snow to replace it

- In some cases, not one but several such cracks occur which present a major obstacle to climbers

- Further down, where the glacier negotiates a bend or a precipitous slope, more crevasses or cracks are formed.

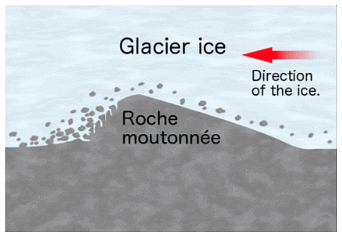

Roche Moutonnée

- Basically, a resistant residual rock hummock or mound, striated by the ice movement.

- Its upstream or stoss side is smoothened by abrasion & its downward or leeward side is roughened by plucking & is much steeper.

- It is believed that plucking may have occurred on the leeward side due to a reduction in pressure of the glacier moving over the stoss slope

- Therefore providing the opportunity for water to refreeze on the lee side and pluck the rock away.

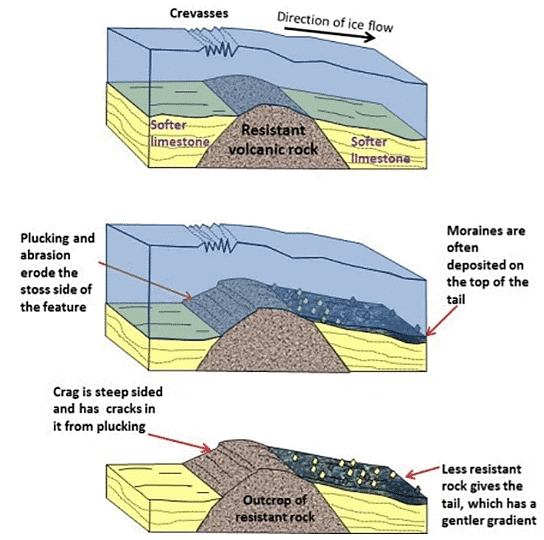

Crag and Tail

- A crag and tail is a larger rock mass than a Roche moutonnee

- Like a Roche moutonnee, it is formed from a section of rock that was more resistant than its surroundings.

- Crag is a mass of hard rock with a steep slope on the upward side, which protects the softer leeward slope from being completely worn down by the oncoming ice.

- It therefore has a gentle tail strewn with the eroded rock debris.

Nunatak

- A nunatak is the summit or ridge of a mountain that protrudes from an ice field or glacier that otherwise covers most of the mountain or ridge. They are also called glacial islands.

- Nunatak is a mountain peak or other rock formation that is exposed above a glacier or ice sheet.

Paternoster Lakes

- A paternoster lake is one of a series of glacial lakes connected by a single stream or a braided stream system.

- Paternoster lakes are formed in the low depression of a U-shaped valley.

- Paternoster lakes are created by recessional moraines, or rock dams, that are formed by the advance and subsequent upstream retreat and melting of the ice.

U shaped glacial Troughs & Ribbon lakes

- Glaciers on their downward journey are fed by several corries scratches & grind the bedrock with straightening out any protruding spurs.

- The interlocking spurs are thus blunted to form truncated spurs with the floor of the valley deepened.

- Hence, the valley which has been glaciated takes the characteristic of U shape, with a wide flat floor & very steep sides.

- After the disappearance of the ice, the deep sections, of these long, narrow glacial troughs may be filled with water forming Ribbon lakes also known as Trough lakes or Finger Lakes.

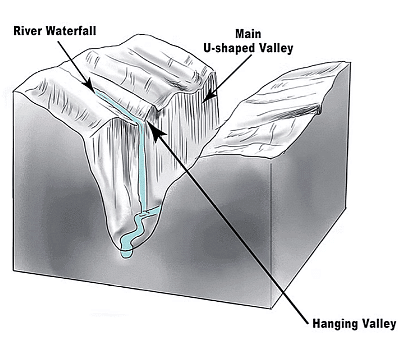

Hanging Valleys

- The main valley is eroded much more than the tributary valley as it contains a much larger glacier.

- After the ice has been melted, a tributary valley hangs above the main valley & plunges down as a waterfall. Such Tributary valleys are termed as hanging valleys.

- Hanging valleys may form a natural head of water for generating hydroelectric power.

Rock Basins and Rock Steps

- A glacier erodes & excavates the bed rock in an irregular manner.

- The unequal excavation gives rise to many rock basins later filled by lakes in valley trough.

- Where a tributary valley joins a main valley, the additional weight of ice in the main valley cuts deeper into the valley floor & deepest at the point of convergence forming rock steps.

- A series of such rock steps may also be formed due to different degrees of resistance to glacial erosion of the bedrocks.

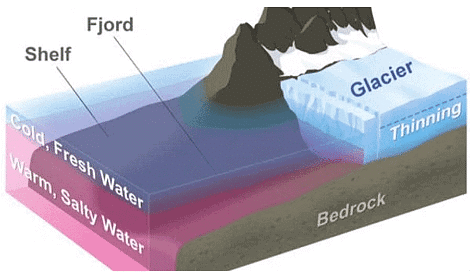

Fjord

- If the glacier flows right down to the sea, it drops its load of moraine in the sea.

- If sections break off as icebergs, moraine material will only be dropped when they melt

- Where the lower end of the trough is drowned by the sea, it forms a deep, steep side inlet called a Fjord, a typical of Norway & Chilean coast.

- Fjords are common in Norway, Greenland and New Zealand.

Glacial Landforms – Depositional

Boulder clay or Glacial till

- This is an unsorted glacial deposit comprising a range of eroded materials such as boulders, sticky clays & fine rock flour.

- It is spread out in sheets, not mounds, & forms gently undulating till or drift plains with monotonous landform.

- The degree of fertility of such glacial plains depends very much on the composition of the depositional materials.

Erratics

- Boulders of varying sizes are transported by ice & left stranded in the regions of deposition when the ice melted, called erratics because they are composed of materials entirely different from those of the regions in which they have been transported.

- Useful in tracing the source & direction of ice movements but their presence in large numbers causes hindrance in farming.

- Also known as perched blocks as sometimes they are found perched in precarious positions as the ice dropped them.

Moraines

- Moraines are made up of pieces of rock that are shattered by frost action, embedded in the glaciers & brought down the valley.

- Those that fall on the sides of the glacier form lateral moraines.

- When two glaciers converge, their inside lateral moraines unite to form a medial moraine.

- The rock fragments which are dragged along, beneath the frozen ice, are dropped when the glacier melts & spread across the floor of the valley as ground moraine.

- The glacier eventually melts on reaching the foot of the valley & the pile of transported materials left behind at the snout is terminal moraine or end moraine.

- The deposition of end moraines may be in several succeeding waves, as the ice may melt back by stages so that a series of recessional moraines are formed.

Drumlins

- Drumlins are oval-shaped hills, largely composed of glacial drift, formed beneath a glacier or ice sheet and aligned in the direction of ice flow.

- They are widespread in formerly glaciated areas and are especially numerous in Canada, Ireland, Sweden, and Finland.

- They are low hills up to 1.5 km long and 60 mm tall & appear steeper on the onset side & taper off at the leeward side.

- They are arranged diagonally & commonly referred as a basket of eggs topography.

- ′Basket of egg topography′ is the topography of drumlins, which are generally found in clusters.

- Drumlin fields are areas with numerous drumlins.

Eskers

- Eskers are the sinuous ridges composed of glacial material mainly sands & gravel deposited by meltwater currents in glacial tunnels

- Glacial tunnels mark the former sites of sub glacial melt water streams

- Their orientation is generally parallel to the direction of glacial flow, and they sometimes exceed 100 kilometers in length.

Outwash Plains

- Made up of fluvio glacial deposits washed out from the terminal moraines by the streams of stagnant ice mass.

- The melt waters sort & redeposit the material mainly consisted of layers of sand and other fine sediments.

- Such plains with their sandy soils are often used for specialized kinds of agriculture, such as the potato.

Kettle lake

- Depressions are formed when the deposition takes place in the form of alternating ridges.

- Shallow, sediment-filled bodies of water formed by retreating glaciers.

Kames

- Small rounded hillocks of sand & gravel which cover part of the plain.

- Kames are often associated with kettles, and this is referred to as kame & kettle topography.

- Kame is also called Hummocks.

Periglacial Landforms

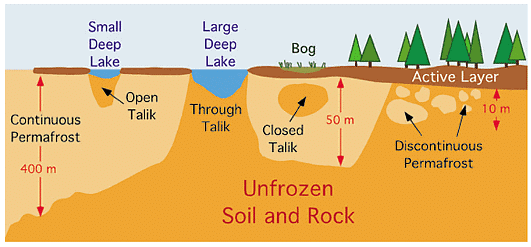

- The term periglacial (near-glacial) literally means around the ice or peripheral to the margins of the glaciers but now this term is used for both ‘periglacial landscape’ and ‘periglacial climate’.

- Periglacial areas are those which are in permanently (perennially) frozen condition but without permanent ice cover on the ground surface.

- The periglacial climate is characterized by mean annual temperature ranging between 1°C and – 15°C and mean annual precipitation of 120 mm to 1400 mm (mostly in solid form).

- Periglacial landform is a feature resulting from the action of intense frost, often combined with the presence of permafrost. Periglacial landforms are restricted to areas that experience cold but essentially nonglacial climates.

- Periglacial regions are very active geomorphological areas. The Mechanical splitting of rocks by ice (gelifraction), frost heaving of the ground (geliturbation), solifluction and nivation are all important processes. In addition, each spring, large quantities of water from melting snow and ice rapidly erode the debris scattered and moved down the slopes. Wind action is also a significant force.

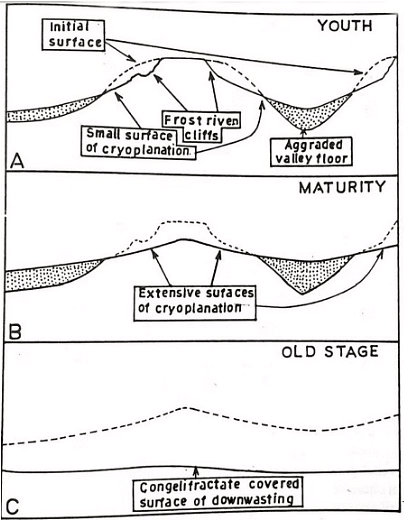

- In 1950 L.C Peltier put forward the concept of a periglacial cycle of erosion. This is similar to the Davisian concept of the normal cycle of erosion, and the periglacial landscape attains old age after passing through the stages of youth and maturity.

- During this entire period there is erosion of the higher parts and deposition in low-lying parts, resulting in overall reduction in relief, and the slope profile gradually becomes smooth and flat. The process by which there is gradual flattering of the surface in the periglacial regions is called ‘cryoplanation’.

- In this process there is parallel retreat of the scarp face by frost shattering and the development and gradual extension of gentle slope at its base by deposition and transport of debris.

- Cryoplanation is thus achieved primarily by the processes of intense frost action or congelifraction and solifluction or congeliturbation. The penultimate landform is a surface of low local relief, not controlled by any base level, and has been called a ‘cryoplain‘ or an ‘altiplain‘.

- The present-day periglacial zones are found in the Arctic regions of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Siberia and also in Antarctica, and the fossil zones of Pleistocene, and other past Ice Ages.

- Permafrost and the active layer are the two most striking features of periglacial areas.

- Permafrost is a condition where a layer of soil, sediment, or rock below the ground surface remains frozen for a period greater than a year (for at least 2 years). Permafrost is not a necessary condition for creating periglacial landforms. However, many periglacial regions are underlain by permafrost and it influences geomorphic processes acting in this region of the world.

- Permafrost is found in about 25 percent of the Earth’s non-glaciated land surface. It occurs wherever the mean annual ground temperature is less than 0° Celsius. Common depths of permafrost are several hundred meters. Most deposits of permafrost have an upper active layer that is between 1 to 3 meters thick. This active layer is subject to a cyclic thaw during the summer season.

Evolution of the Periglacial Erosion Cycle

The evolution of the periglacial erosion cycles its different stages have been as:

Stage 1 (Initial surface)

- The cycle begins with the onset of periglacial conditions. In this initial stage congelifraction is especially active as a result of which there is shattering of the bare rocks on the upper slopes, and block fields are formed by the accumulation of angular rock fragments.

Stage 2 (Early or young stage)

- The rock fragments move downhill along the slope by gravity, and talus or congeliturbate mantled slope is formed at the base of the slope.

- During this period nivation hollows, as well as cryoplanation terraces, also begin to be formed on the higher slopes.

- Till the end of the young stage, the scarp of the terraces starts retreating by frost action, and the terrace benches are extended by scarp retreat.

Stage 3 (Mature Stage)

- With further passage of time, the scarps are destroyed by continual recession and in their place only residual or for features are left on the summits or slopes.

- This is the beginning of maturity when the original landscape is lost and the valleys and lower slopes are covered with a mantle of frost shattered and soliflucted materials.

Stage 4 (Old Stage of cryoplanation)

- Towards the end of maturity and in old age, the higher land is further reduced and levelled on account of solifluction, and the accumulation of debris goes on increasing in the neighbouring valleys and low-lying lands, and the periglacial surface is converted into an almost level plain.

- The debris becomes fine on account of continual frost weathering and solifluction (gelifluction) by further disintegration and abrasion.

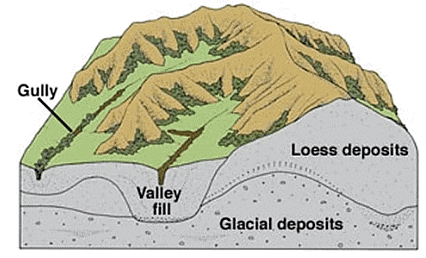

- The finer debris is transported by the wind, and loess and sand dunes are formed at places, and areas of ventifacts and lag deposits develop by the blowing away of finer materials by the wind.

Taking the different slope forms found in periglacial regions as the basis, Peltier has tried to synthesize them and arrange them in a sequence. His hypothesis thus provides an overall framework for the understanding of the slope evolution in periglacial regions, but it does not provide an analysis of how exactly slope form is influenced by frost shattering and solifluction. Further, adequate attention has not been paid to other processes, especially the influence of running water.

But the concept of scarp recession by frost shattering and the resultant extension of the terraces is by itself an important and useful concept that helps us to understand the formation of cryoplanation terraces, summit tors, nivation hollows & cryopedimerts.

Periglacial Landforms – Erosional

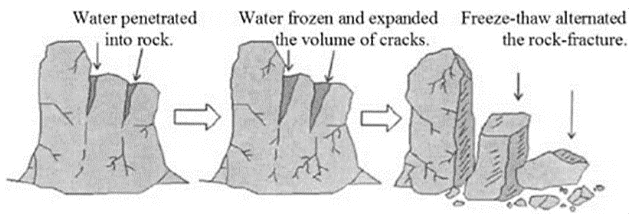

Freeze-Thaw Cycle

- Freeze-thaw weathering is a process of erosion that happens in cold areas where ice forms. A crack in a rock can fill with water which then freezes as the temperature drops. As the ice expands, it pushes the crack apart, making it larger. When the temperature rises again, the ice melts, and the water fills the newer parts of the crack. The water freezes again as the temperature falls, and the expansion of the ice causes further expansion to the crack. This process continues until the rock breaks.

Nivation Hollow

- Hollows produced by snow-patch erosion or nivation are called nivation hollows which are generally found along the hillsides in various forms. They extend from a few metres to 1.5 kilometres.

- In time, these hollows may trap more snow and may deepen further with more nivation so that cirques or thermocirques are formed.

- They are classified on the basis of shape into: (i) Transverse hollows (ii) Longitudinal hollows.

Asymmetrical Valley

- An asymmetric valley is a valley that has steeper slopes on one side. Valley has one side steeper than the other, the opposing slopes having significantly contrasting angles.

- This contrast may be caused by geologic structure or variation in the nature and intensity of erosional (e.g. periglacial) processes and there may be contrasts in the vegetation on the opposing slopes.

- Such valleys are common in past and present periglacial environments, where aspect has a significant effect on the nature of frost-based processes and on the depth of the active layer.

Cryoplanation Terraces or Goletz Terraces

- Cryoplanation terraces (also known as altiplanation or goletz terraces and by several other terms) are periglacial landforms consisting of nearly horizontal bedrock surfaces or benches backed by frost-weathered bedrock cliffs.

- Cryoplanation Terraces (CTs) are erosional landforms reminiscent of giant staircases, with alternating shallow sloping treads and steep scarps leading to extensive flat summits.

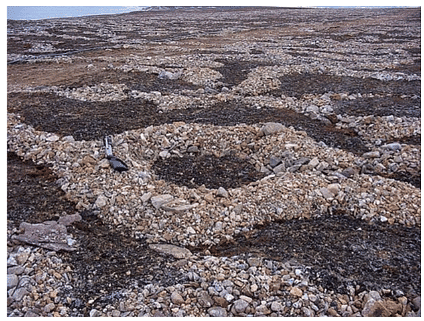

Patterned Ground

- When Ice from below makes upward pressure the overlying sedimendary flat rocks are being weathered and cracks are developed, these cracks it seems are having some pattern on ground.

- A process called frost heaving is responsible for these features.

Stone Strips

- A stone stripe is an elongated concentration of mostly talus-like basalt rock found along a hillside or the base of a cliff. Many stone stripes occur without cliffs.

- Stone stripes are thought to have been originally created by periglacial conditions of the Quaternary period during an Ice age. It is likely their formation originates from multiple processes including frost action, surface erosion, eluviation, and mass wasting. However, it is likely that intense freeze and thaw cycles account for the natural sorting of the rock debris within a stone stripe, and also accounts for the shallow depth of the stripes, since frost penetration is thought to not penetrate deeper than 1 meter in the region.

- A stone stripe is identified by its lack of vegetative cover.

Pingo

- Pingo is an Eskimo word that means isolated dome-like low mounds or hills found in permafrost areas. This word was first used by A.E. Porsild in the year 1938. They are found in continuous as well as discontinuous permafrost areas.

- They are abundantly found in the arctic areas (65° N ) of Canada, Alaska, Greenland and Siberia.

- They range in height from a few metres to 60 metres (sometimes they are as high as 100 metres) and from a few metres to 300 metres in diameter. Small pingos have closed tops whereas big pingos have open tops.

Hummocks

- Small upstanding wrinkles on the surface of permafrost are called hummocks. These are formed due to squeezing of the ground surface because of lateral pressure exerted by freezing of active layer.

Palsa

- A special category of hummock found in swampy areas and composed of peats having thin ice layers inside is called palsa which is about 10m in height and 10 to 20 m in diameter and is mostly found in the periglacial environment of arctic and subarctic areas.

- Palsa may be destroyed by rise in water table in the nearby swamps or by fracture in its upper surface.

- It is formed by frost heaving under the influence of ice segregation.

Periglacial Landforms – Depositional

BlockFields or Felsenmeer

- Blockfields are areas covered by large angular blocks, traditionally believed to have been created by freeze-thaw action.

- Block field refers to the natural collection of large stone blocks at the flat surface of the hill tops in the periglacial areas. These block fields are also called blockmeer and falsenmeer. The stone blocks are formed due to frost weathering (congelifraction).

Patterned Ground

- Blockfields sometimes takes some geometrical shapes (like circles, polygons, nets, stripes and garlands) and are so systematically arranged are called Patterned Ground.

- Patterned Ground is erosional as well as depositional landforms in periglacial.

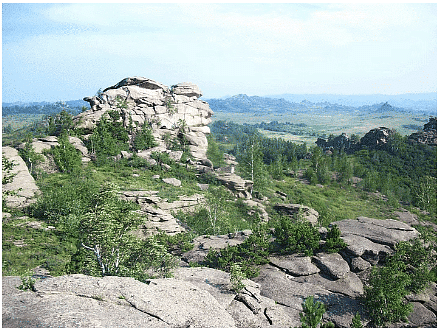

Tors

- Tors, one of the most controversial landforms, are piles of broken and exposed masses of hard rocks having a crown of rock blocks of different sizes on the top and clitters (trains of blocks) on the sides. The rock blocks, main components of tors, may be cuboidal, rounded, angular, elongated etc. in shape.

- They may be seated at the top of the hills, on the flanks of the hills or on flat basal platforms ranging from 6 m to 30 m in height. They are found in different climates varying from cold to hot and dry to humid. Though tors have developed over almost all types of rocks but they are frequently found in the regions of granites.

Boulder Fields

- Boulder Field is a periglacial feature that formed as a direct result of its proximity to the end moraine. Accumulations of rock debris in the valley floors are called stone streams or boulder fields.

- The stone is well sorting of rock debris in the stone streams. The upper layer consists of large and coarse debris while the lower layer is dominated by fine materials. Water channel is developed between the valley walls and stone stream. Sorting of rock debris occurs through the process of frost Heaving. Stone streams move downslope due to the force of gravity, frost heaving and solifluction.

Desert Landforms/Arid Landforms

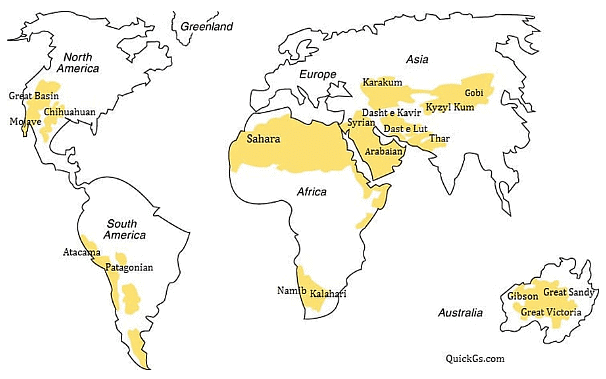

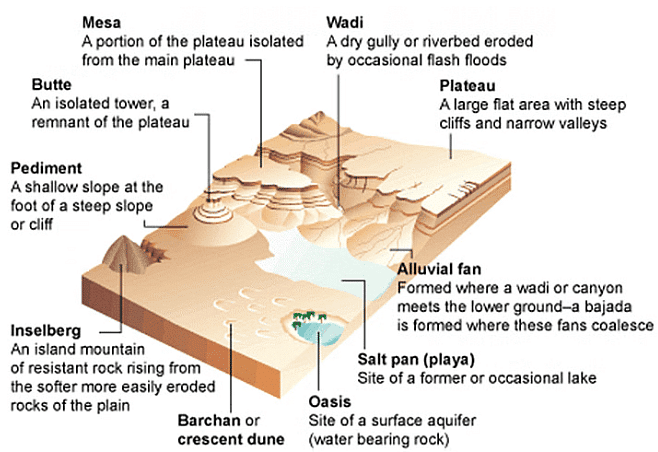

Desert

- A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to the processes of denudation. About one-third of the land surface of the world is arid or semi-arid.

- This includes much of the Polar Regions, where little precipitation occurs, and which are sometimes called polar deserts or “cold deserts“. Deserts can be classified by the amount of precipitation that falls, by the temperature that prevails, by the causes of desertification, or by their geographical location.

- About 1/5 of the world’s land is made up of deserts.

- Deserts that are absolutely barren, where nothing grows are known as true deserts.

- Insufficient & irregular rainfall, high temperature & rapid rate of evaporation are the main causes of the desert’s aridity.

- Almost all the deserts are confined within 15 degree – 30 degree parallels to N-S of the equator known as trade wind deserts or tropical deserts.

- They lie in the trade wind belt on the western parts of the continents.

- Offshore trade winds are often bathed in cold currents which produces a desiccating (dehydrating) effect, hence moisture is not easily condensed into precipitation.

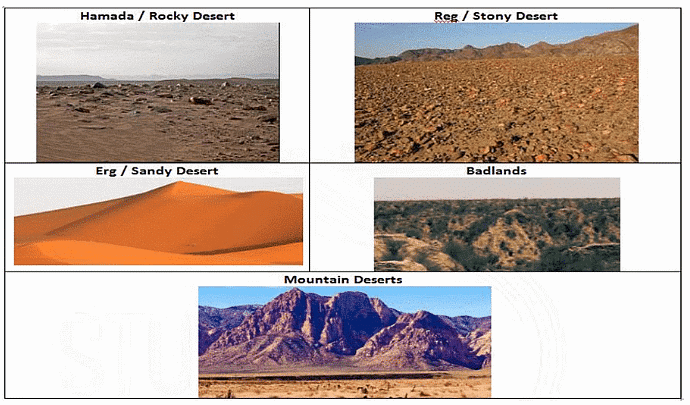

Types of Desert

- Hamada/Rocky Desert

- Consist of large stretches of bare rocks, swept clear of sand & dust by wind.

- Exposed rocks are thoroughly smoothened, polished & highly sterile

- Reg/Stony Desert

- Composed of extensive sheets of angular pebbles & gravels which the wind is not able to blow off.

- Stony deserts are more accessible than sandy deserts & large herds of camels kept there.

- Erg/Sandy Desert

- Also known as the sea of sand

- Winds deposit vast stretches of undulating sand dunes in the direction of winds

- Badlands

- Consists of gully & ravines formed on hill slopes & rock surfaces by the extent of water action

- Not fit for agriculture & survival

- Finally leads to the abandonment of the entire region by its inhabitant

- Mountain Deserts

- Deserts which are found on the highlands such as on plateaus & mountain ranges, where erosion has dissected the desert highland into rough chaotic peaks & uneven ranges.

- Their steep slopes consist of Wadis (dry valleys) with sharp & irregular edges carved due to the action of frost.

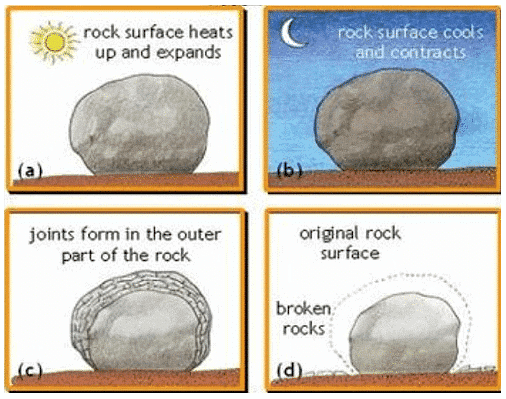

Mechanism of Desert/Arid Erosion

- Weathering

- Most potent factor in reducing rocks to sand in arid regions.

- Even though the amount of rain that falls in a desert is small, but manages to penetrate into rocks & sets up chemical reactions in various minerals it contains.

- Intense heating during the day & rapid cooling during the night by radiations, set up stresses in already weakened rocks, hence they eventually crack.

- When water gets into cracks of a rock, it freezes at night as the temperature drops below the freezing point & expands by 10 % of its volume.

- Successive freezing will prise of fragments of rocks which get accumulated as screes.

- As heat penetrates rock, its outer surface gets heated & expands, leaving its inner surface comparatively cool.

- Hence, outer surface prise itself from the inner surface & peels

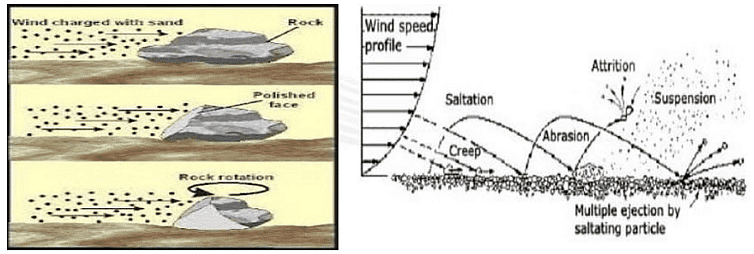

Action of Wind

- Efficient in arid regions as little vegetation or moisture to bind the loose surface materials.

It is carried out in the following ways:

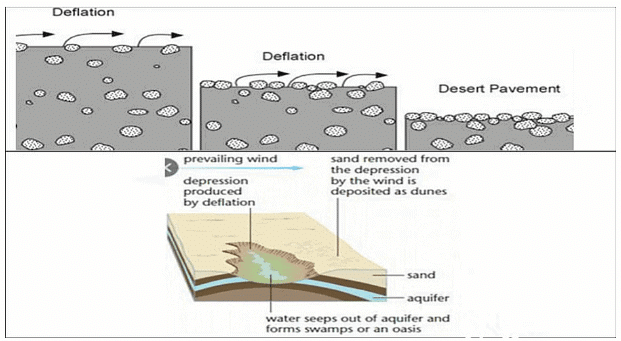

- Deflation

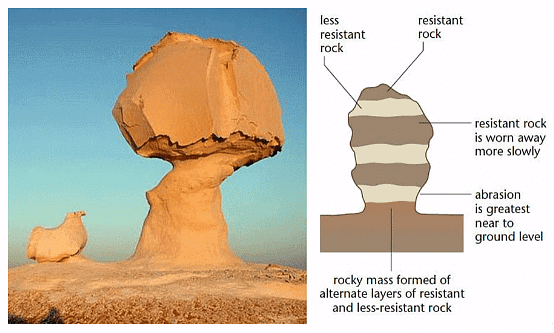

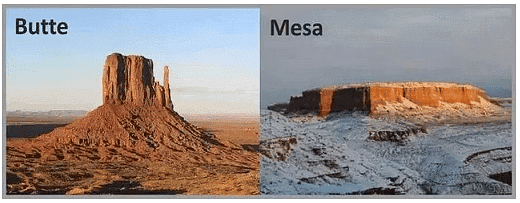

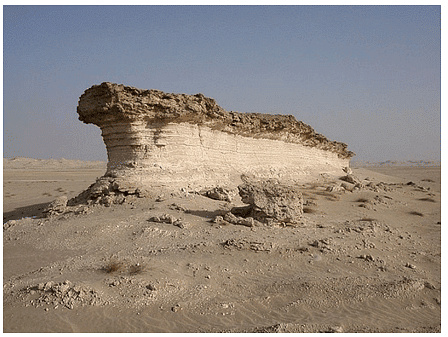

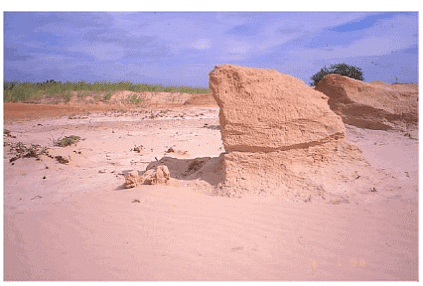

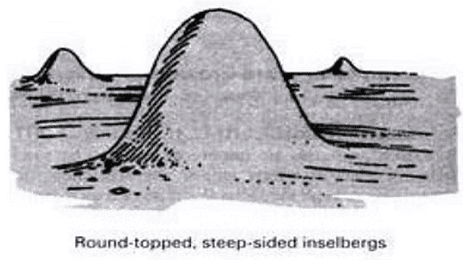

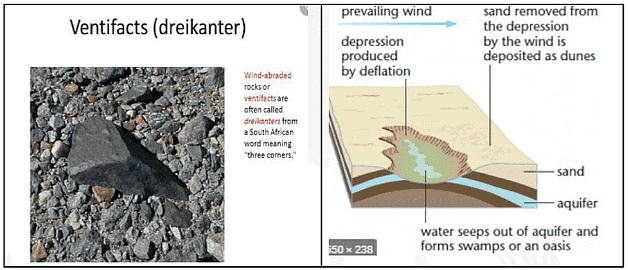

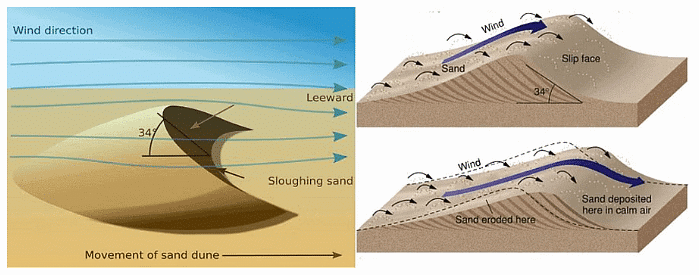

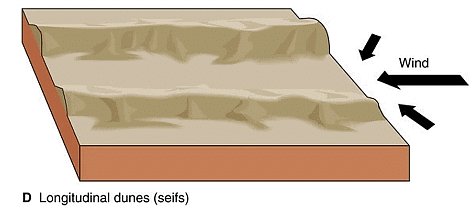

- Involves lifting & blowing away of loose materials from the ground