Laxmikant Summary: Landmark Judgements and Their Impact- 3 | Indian Polity for UPSC CSE PDF Download

21. Unni Krishnan Case (1993)

- Name of the Case: Unni Krishnan vs. State of A.P.

- Year of Judgement: 1993

- Popular Name: Right to education

- Related Topic/Issue: Right to education

- Related Article/Schedule: Articles 21 & 45

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court held that the right to education is a fundamental right under Article 21, stemming directly from the right to life. However, it clarified that only children have the right to free education until they reach the age of 14. After this age, the state's obligation to provide education depends on its economic capacity and development. The court emphasized following the directives in Article 45, which originally (before the 2002 amendment) mandated free and compulsory education for all children up to the age of 14. The obligations outlined in Articles 41, 45, and 46, part of the Directive Principles of State Policy, can be fulfilled by the state through its institutions or by supporting private educational institutions. Private unaided institutions offering professional courses like engineering and medicine are allowed to charge higher fees but within set limits, and commercialization of education is not permitted.

Impact of the Judgement

Following this judgement, the 86th Amendment Act (2002) was enacted, introducing a new Article 21A, establishing the right to education as an independent fundamental right. This Article mandates the state to provide free and compulsory education for children aged six to fourteen, and to give effect to this, the Parliament passed the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009.

22. Supreme Court Advocates.on.Record Association Case (1993)

- Name of the Case: Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association vs. Union of India

- Year of Judgement: 1993

- Popular Name: Second Judges case

- Related Topic/Issue: Appointment of Supreme Court and High Court Judges

- Related Article/Schedule: Articles 124 & 217

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court overturned its previous verdict in the S. P. Gupta case (1981), commonly known as the First Judges case. It ruled that the President shall appoint judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts based on advice from the Chief Justice of India. However, the Chief Justice of India must consider the opinions of two of his senior colleagues before offering advice. This implies a shift in interpreting 'consultation' in Articles 124(2) and 217(1) to 'concurrence'. Additionally, the court mandated the appointment of the most senior judge of the Supreme Court as the Chief Justice of India.

Impact of the Judgement

Following this judgement and the Advisory Opinion in the Third Judges case (1998), a Memorandum of Procedure for judge appointments to the Supreme Court and High Courts was devised and is currently adhered to. This process, known as the "collegium system," was initiated by the judiciary.

23. S.R. Bommai Case (1994)

- Name of the Case: S.R. Bommai vs. Union of India

- Year of Judgement: 1994

- Popular Name: President's rule

- Related Topic/Issue: Article 356

- Related Article/Schedule: Article 356

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court affirmed the constitutional validity of imposing President's rule under Article 356 in Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Rajasthan in 1992. However, it deemed the imposition of President's Rule in Nagaland in 1988, Karnataka in 1989, and Meghalaya in 1991 as unconstitutional and invalid. Additionally, the court established key propositions regarding Article 356:

- The proclamation issued by the President under Article 356(1) is subject to judicial review.

- The burden lies on the Union Government to demonstrate the existence of relevant material justifying the proclamation.

- Article 74(2) does not prevent scrutiny of the material used by the President in reaching satisfaction.

- If the President's proclamation is declared invalid, the court has the authority to restore the Legislative Assembly and the Ministry, even if approved by both Houses of Parliament.

- Secularism is an integral part of the basic structure of the constitution, and anti-secular acts by a State Government can be a lawful ground for imposing President's Rule.

Impact of the Judgement

This judgement imposed a check on the arbitrary exercise of power under Article 356 by the Centre for imposing President's Rule in the States.

24. Vishaka Case (1997)

- Name of the Case: Vishaka vs. State of Rajasthan

- Year of Judgement: 1997

- Popular Name: Sexual harassment of women at the workplace

- Related Topic/Issue: Articles 15 and 21

- Related Article/Schedule: Articles 15 and 21

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court declared that sexual harassment of women in the workplace violates Articles 15 and 21 of the Constitution. It emphasized the responsibility of employers or other relevant individuals in both public and private work environments to prevent sexual harassment of female employees. The court provided detailed guidelines on the matter, mandating their strict adherence by all employees until appropriate legislation is enacted on the subject.

Impact of the Judgement

By establishing a set of guidelines known as the 'Vishaka Guidelines,' this judgement addressed the legislative gap on the issue. Before this, there was no specific domestic law dealing with sexual harassment at the workplace, except for some provisions in the Indian Penal Code. Subsequently, the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act, 2013, was enacted to offer protection against sexual harassment and provide mechanisms for addressing complaints.

25. Vineet Narain Case (1997)

- Name of the Case: Vineet Narain vs. Union of India

- Year of Judgement: 1997

- Popular Name: Jain Hawala case

- Related Topic/Issue: Autonomy and efficient functioning of CBI

- Related Article/Schedule: Not specified

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court directed the conferment of statutory status upon the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC). Additionally, it issued directives to transform the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) into an autonomous body, ensuring effective and non-partisan functioning. Similar directions were given for the Enforcement Directorate (ED). The court also invalidated the arbitrary provision of the Single Directive, which mandated prior permission from the Central Government for the CBI to investigate officers of the rank of Joint Secretary and above.

Impact of the Judgement

This judgement led to the enactment of the CVC Act, 2003, granting statutory status to the CVC. The Act vested the superintendence of the CBI, particularly in corruption cases, with the CVC. However, it's noteworthy that the Act reinstated the Single Directive, which was subsequently declared invalid by the Supreme Court in 2014, citing a violation of Article 14.

26. Association for Democratic Reforms Case (2002)

- Name of the Case: Union of India vs. Association for Democratic Reforms

- Year of Judgement: 2002

- Popular Name: Poll Reforms case

- Related Topic/Issue: Criminalization of politics

- Related Article/Schedule: 19

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court held that voters have the right to know about the antecedents, including the criminal past, of their candidates, as part of their right under Article 19(1)(a) - freedom of speech and expression. The court emphasized that informed voters are crucial for free and fair elections, a cornerstone of democracy. Consequently, the Election Commission was directed to make it mandatory for candidates to provide information on: (a) Past criminal convictions; (b) Pending criminal cases; (c) Assets and liabilities; and (d) Educational qualifications.

Impact of the Judgement

Following this judgement, the Election Commission, in 2003, issued an order requiring candidates seeking election to Parliament or a State Legislature to furnish the specified information on their nomination papers. Providing false information in the affidavit is now considered an electoral offence.

27. T.M.A. PAl Foundation Case (2002)

- Name of the Case: T.M.A. Pai Foundation vs. State of Karnataka

- Year of Judgement: 2002

- Popular Name: Rights of minority educational institutions

- Related Topic/Issue: 29 & 30

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court established key principles regarding the rights and permissible restrictions on minority educational institutions, both aided and unaided. These include:

- (a) Linguistic and religious minorities, covered by Article 30, are determined state-wise.

- (b) Article 30(1) grants the right to establish and administer educational institutions of choice, even for professional education.

- (c) Admission to unaided minority institutions is not regulatable by the state, except for basic eligibility conditions.

- (d) Regulatory measures are allowed for maintaining educational standards.

- (e) Once aid is received, the institution is governed by Article 29(2) and cannot discriminate based on religion, race, caste, or language.

- (f) Aided professional institutions may require a common entrance test for admission.

- (g) Minority institutions must follow a fair and transparent admission procedure, emphasizing merit in professional and higher education.

Impact of the Judgement

To counter the effects of this judgement and the Mandar case (2005), the 93rd Amendment Act (2005) was enacted. This amendment empowered the state to make special provisions for socially and educationally backward classes, scheduled castes, or scheduled tribes regarding admission to educational institutions, including private ones, except minority educational institutions under Article 30(1).

28. Naveen Jindal Case (2004)

- Name of the Case: Union of India vs. Naveen Jindal

- Year of Judgement: 2004

- Popular Name: Right to fly the national flag

- Related Topic/Issue: 19

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court ruled that the right to fly the national flag freely with respect and dignity is a fundamental right of a citizen, falling under the freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a). This right represents a citizen's allegiance and feelings of pride for the nation. However, it clarified that this right should not be utilized for commercial purposes or otherwise.

29. Prakash Singh Case (2006)

- Name of the Case: Prakash Singh vs. Union of India

- Year of Judgement: 2006

- Popular Name: Police reforms

- Related Topic/Issue: Supreme Court Judgement

Supreme Court Judgement

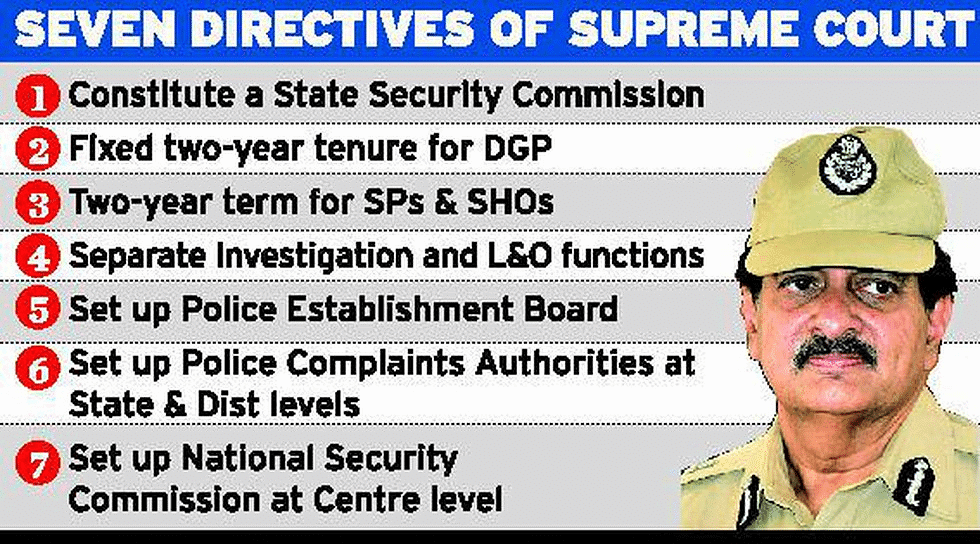

The Supreme Court issued seven directives to the central government, state governments, and union territories with the aim of implementing police reforms, ensuring that the police machinery functions without any political interference. These directives include the constitution of a State Security Commission, selection of the DGP from amongst the three senior-most officers empanelled by the UPSC, a minimum tenure of two years for the DGP and officers on operational duties, separation of the investigation police from the law and order police, establishment of a Police Establishment Board, creation of Police Complaints Authority at state and district levels, and establishment of a National Security Commission at the central level.

Impact of the Judgement

This judgement resulted in the introduction of partial police reforms in the country, as it could not completely eliminate political interference in the functioning of the police system, particularly in postings and transfers. Although State Security Commissions and Police Establishment Boards have been set up in most states, their effectiveness is limited, and they lack the authority to make binding recommendations. However, in various cases, High Courts have issued orders directing state governments to comply with the Supreme Court's directives.

30. M. Nagaraj Case (2006)

- Name of the Case: M. Nagaraj vs. Union of India

- Year of Judgement: 2006

- Popular Name: Reservation in promotions for SCs and STs

- Related Topic/Issue: Supreme Court Judgement

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the 77th Amendment Act (1995), the 81st Amendment Act (2000), the 82nd Amendment Act (2000), and the 85th Amendment Act (2001). It stated that these amendments, which inserted Article 16(4A) and Article 16(4B), derive from Article 16(4) and do not alter its structure. They retain the controlling factors of backwardness and inadequacy of representation, allowing the state to provide reservation while considering the overall efficiency of the State administration under Article 335. These amendments specifically apply to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and do not eliminate constitutional requirements such as the 50% ceiling limit, the concept of creamy layer, the sub-classification between OBCs, SCs, and STs, as established in the Indra Sawhney case (1992) and the post-based roster concept with the inherent concept of replacement, as held in the R.K. Sabhaywal case (1995).

|

150 videos|780 docs|202 tests

|

FAQs on Laxmikant Summary: Landmark Judgements and Their Impact- 3 - Indian Polity for UPSC CSE

| 1. What is the Unni Krishnan case of 1993? |  |

| 2. What is the significance of the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association case of 1993? |  |

| 3. What is the S.R. Bommai case of 1994? |  |

| 4. What is the Vishaka case of 1997? |  |

| 5. What is the significance of the Association for Democratic Reforms case of 2002? |  |