Legal Current Affairs for CLAT (October 2024) | Legal Reasoning for CLAT PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Section 6A of the Citizenship Act,1955 |

|

| Discriminatory Attitude Towards Women |

|

| Right to Free Legal Aid |

|

| Power of State to Regulate Industrial Alcohol |

|

| Adhaar Card |

|

| Tirupati Laddu Case |

|

Section 6A of the Citizenship Act,1955

Why in the News?

The Supreme Court of India upheld the constitutional validity of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, which recognizes the Assam Accord, with a 4:1 majority. The majority opinion, led by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud, emphasized balancing humanitarian concerns with protecting the local population. However, dissenting Justice Pardiwala argued that the provision had become unconstitutional over time due to its arbitrary nature and ineffective enforcement mechanisms.

Background of In Re: Section 6A Citizenship Act 1955

The case revolves around Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955, introduced in 1985 via the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, following the Assam Accord – an agreement between the Indian government and Assam movement leaders. Section 6A provided special provisions for migrants from Bangladesh to Assam, classifying them into two categories:

- Migrants who entered before 1st January 1966.

- Migrants who entered between 1st January 1966 and 25th March 1971, with the cut-off date chosen due to the Bangladesh Liberation War and the resulting refugee crisis.

In 2012, the Assam Sanmilita Mahasangha, a civil society group from Guwahati, challenged this provision, arguing that it discriminated against Assam by having different citizenship rules compared to other states. The petitioners claimed it violated constitutional principles, such as the right to cultural preservation, the political rights of Assam’s citizens, and India’s democratic and federal structure. The main issue at hand was whether the law adequately protected Assam’s indigenous population while addressing the humanitarian needs of migrants who had settled in the state for decades.

Court’s Observations

The Supreme Court upheld Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955, as constitutionally valid by a 4:1 majority, recognizing it as a legitimate solution to address illegal migration in Assam.

- The Court found that Section 6A was in line with Articles 6 and 7 of the Indian Constitution, addressing migration to Assam with rational cut-off dates based on historical events like the Bangladesh Liberation War.

It classified immigrants in Assam into three categories:

- Pre-1966 migrants were deemed Indian citizens.

- Migrants from 1966-1971 could seek citizenship after meeting eligibility conditions.

- Post-25th March 1971 migrants were considered illegal immigrants, subject to deportation.

- The Court rejected claims that Section 6A violated Article 29(1), finding no evidence of harm to Assamese cultural or linguistic rights.

- The geographic specificity to Assam was deemed reasonable due to the state’s unique demographic situation, with significant migration despite its small land area compared to other border states.

- The Court called for stronger enforcement mechanisms, including the creation of a monitoring bench to oversee the detection and deportation of illegal immigrants.

- Justice Pardiwala, in dissent, considered Section 6A unconstitutional, citing its temporal unreasonableness and procedural flaws in the detection mechanism.

- The majority opinion affirmed Parliament's authority to enact Section 6A, emphasizing that it strikes a balance between humanitarian concerns and the interests of the local population.

- The Court also directed the strengthening of Foreigners Tribunals and other statutory machinery to ensure the timely implementation of the law.

What is Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955?

Section 6A was introduced as a special provision to address the citizenship status of people covered under the Assam Accord, specifically for individuals who migrated to Assam before the Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 1985 came into force.

- It defines a person of Indian origin as someone born in undivided India or whose parents or grandparents were born in India.

- Section 6A distinguishes between two categories of immigrants:

- Those who entered Assam before 1st January 1966: Deemed Indian citizens from 1st January 1966.

- Those who entered between 1st January 1966 and 24th March 1971: Eligible for citizenship after registration and a 10-year waiting period.

For the 1966-1971 category, the law includes the following:

- Detection as a foreigner by a Tribunal under the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964.

- Mandatory registration with designated authorities.

- Deletion from electoral rolls upon detection.

- A 10-year waiting period for full citizenship rights, with the interim period granting most rights except the ability to vote.

- After the 10-year waiting period, full citizenship rights are granted.

The law also provides an opt-out mechanism:

- A 60-day window for pre-1966 entrants to declare non-desire for Indian citizenship.

- A similar option for 1966-1971 entrants to opt out of the registration process.

Section 6A also excludes:

- Individuals who were already Indian citizens before the 1985 amendment.

- Individuals expelled from India under the Foreigners Act, 1946.

The provision has overriding effect over other laws, unless explicitly stated otherwise within Section 6A.

Citizenship under the Indian Constitution

- Article 5 (Citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution): Grants citizenship to people domiciled and born in India, as well as those whose parents were born in India.

- Article 6 (Citizenship of certain persons migrated from Pakistan): Grants citizenship to those who migrated from Pakistan before 19th July 1949, if they meet specific criteria.

- Article 7 (Citizenship of certain persons migrated to Pakistan): Provides citizenship to those who migrated to Pakistan after 1st March 1947 but later returned to India with a resettlement permit.

- Article 8 (Person of Indian origin residing outside India): Allows persons of Indian origin residing outside India to register as Indian citizens.

- Article 9: Affirms the concept of single citizenship, barring individuals who acquire the citizenship of another country.

- Article 10: Ensures that Indian citizens remain subject to Indian laws.

- Article 11: Grants Parliament the authority to make laws regarding the acquisition and termination of citizenship.

Discriminatory Attitude Towards Women

Why in the News?

The Supreme Court recently granted relief to Manisha Ravindra Panpatil, a female Sarpanch disqualified on technical grounds, highlighting the discriminatory attitudes faced by women in rural governance. The Court emphasized the gravity of removing an elected representative, especially a woman in a reserved position, pointing out systemic biases within administrative processes that challenge women’s leadership. Justices Surya Kant and Ujjal Bhuyan made these observations in the case of Manisha Ravindra Panpatil v. The State of Maharashtra & Ors.

Background of Manisha Ravindra Panpatil v. The State of Maharashtra & Ors.

Manisha Ravindra Panpatil was elected as the Sarpanch (village head) of Gram Panchayat, Vichkheda, in Jalgaon District, Maharashtra, in February 2021. Following her election, some villagers (private respondents) filed a disqualification petition against her, alleging that she resided with her mother-in-law in a house built on government land.

Panpatil contested the allegations, clarifying that she lived separately with her husband and children in a rented house, and the disputed property was in such poor condition that it couldn’t be inhabited. Despite her defense, the local Collector issued an order disqualifying her, which was upheld by the Divisional Commissioner. Panpatil then appealed to the Bombay High Court (Aurangabad Bench), but her petition was dismissed on technical grounds on 3rd August 2023.

Subsequently, she filed a Special Leave Petition (SLP) before the Supreme Court of India. Notably, no objections regarding land encroachment were raised when she originally filed her nomination for Sarpanch.

Special Leave Petition

Special Leave Petitions (SLPs) hold significant importance in the Indian judicial system. Under Article 136 of the Indian Constitution, the Supreme Court can entertain SLPs in cases involving substantial questions of law. This power allows the Court to grant special leave to appeal against any judgment or order passed by any court or tribunal in India.

Court’s Observations

The Court noted that the issue in this case was rooted in the village residents’ inability to accept a woman as their elected Sarpanch, highlighting resistance to a female leader’s authority. The Court pointed out that since no professional misconduct was found, the private respondents resorted to making baseless allegations to remove her from office.

The Court criticized the government authorities at various levels for passing summary orders without proper fact-finding. There was no credible evidence to support the claim of land encroachment, and the removal of an elected representative, particularly a woman from a rural area, was treated with undue casualness. The Court acknowledged that women face significant challenges in securing public office and that allegations like these, leading to removal, were disproportionate and discriminatory.

The Court emphasized that such actions undermine efforts toward gender parity and women’s empowerment in public offices. It directed that authorities must sensitize themselves and foster a more conducive environment for women representatives. The treatment of this case, in particular, was seen as detrimental to the broader goal of adequate female representation in elected bodies.

Landmark Judgments That Changed the Course for Women in India

Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan (1997):

- Defined sexual harassment at the workplace and provided guidelines for its prevention.

- Made employers responsible for ensuring a safe work environment for women.

Mary Roy v. State of Kerala (1986):

- Granted Syrian Christian women equal inheritance rights.

- Invalidated the Travancore Christian Succession Act, which gave women limited property rights.

Ahmad Khan v. Shah Bano Begum (1985) (Shah Bano case):

- Upheld the right of Muslim women to maintenance beyond the iddat period under Section 125 of the CrPC.

- Sparked nationwide discourse on a uniform civil code.

Laxmi v. Union of India (2014):

- Led to stricter regulations on the sale of acids and compensation for acid attack victims.

- Made acid attacks a non-bailable offense.

Indian Young Lawyers Association v. The State of Kerala (Sabarimala Case, 2018):

- Lifted the ban on women of menstruating age entering the Sabarimala temple.

- Held that physiological features cannot be a basis for denying constitutional rights.

Joseph Shine v. Union of India (2018):

- Decriminalized adultery by striking down Section 497 of the IPC.

- Emphasized women’s sexual autonomy within marriage.

Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma (2020):

- Granted daughters equal coparcenary rights in Hindu Undivided Family property.

- Made the right retroactive, applying to living daughters of living coparceners.

Secretary, Ministry of Defence v. Babita Puniya (2020):

- Granted permanent commission to women officers in the Indian Army.

- Rejected arguments based on physiological limitations, emphasizing equal opportunities.

Aprna Bhat v. The State of Madhya Pradesh (2021):

- Addressed problematic bail conditions in sexual harassment cases, such as forcing the accused to visit the victim with rakhi and sweets.

- Mandated gender sensitization training for judges and legal personnel.

- Set guidelines to avoid gender stereotyping in bail conditions and emphasized the seriousness of sexual offenses.

Right to Free Legal Aid

Why in the News?

A bench comprising Justice KV Viswanathan and Justice BR Gavai recently issued guidelines regarding the provision of free legal aid to prison inmates in the case Suhas Chakma v. Union of India & Others.

Background of Suhas Chakma v. Union of India & Others Case

In this case, a writ petition was filed under Article 32 of the Constitution of India. The petition raised several issues, including:

- Directing the Union of India, States, and Union Territories to ensure that no prisoner is subjected to torture, cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment due to overcrowded and unhygienic conditions in jails.

- Ensuring that all individuals deprived of their dignity are treated with respect for their inherent dignity.

- Establishing a permanent mechanism to address the issue of overcrowded prisons.

On 17th May 2024, the Court identified two key issues:

- Open Correctional Institutions.

- Modalities for lawyer visits to jails to ensure that prisoners receive free legal aid.

This judgment specifically focuses on the provision of free legal aid to prison inmates.

Court’s Observations

The Court issued several directions regarding free legal aid for prison inmates, including:

Implementation of SOPs for Legal Aid: The Court directed that the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA), in collaboration with State Legal Services Authorities (SLSAs) and District Legal Services Authorities (DLSAs), ensure that the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for prisoner access to legal services and the functioning of Prison Legal Aid Clinics (PLACs) are effectively implemented.

Monitoring and Review: Legal Services Authorities at various levels must strengthen the monitoring of PLACs and periodically review their functioning. They must also update statistical data regularly.

Maximizing Legal Aid: The Legal Services Authorities must ensure that the Legal Aid Defence Counsel System operates to its fullest potential. Awareness of legal aid mechanisms is essential, and the Court instructed the establishment of a robust system to reach as many individuals as possible.

Awareness Campaigns: The Court outlined several steps to raise awareness about legal aid services:

- Displaying boards at public places like police stations, post offices, bus stands, and railway stations, showing contact details for legal aid offices.

- Running promotional campaigns on radio and digital platforms, as well as organizing creative initiatives such as street plays.

Pre-litigation Assistance: NALSA’s "Early Access to Justice at Pre-arrest, Arrest, and Remand Stage Framework" should be actively pursued, with periodic reviews of the work done under this framework.

Interaction with Convicts and Lawyers: The Court directed that interactions should be conducted with convicts who have not filed appeals, and that periodic meetings should be held with Jail Visiting Lawyers (JVLs) and Para Legal Volunteers (PLVs) to ensure their knowledge is up-to-date.

Education and Resources for Lawyers: Legal Services Authorities must ensure continuing education for lawyers involved in pre-litigation assistance and those working with the Legal Aid Defence Counsel System. Additionally, access to law books and online libraries should be provided to these lawyers.

Digitization and Reporting: Periodic reports from DLSAs to SLSAs and NALSA must be submitted, with a focus on digitizing all relevant records.

Cooperation from Governments: The Court emphasized that both the State Government and the Union of India must continue to cooperate with Legal Services Authorities at all levels for the effective implementation of these measures.

Judicial Awareness: The Court also directed that copies of the judgment be forwarded to all High Courts, recommending that courts include information about free legal aid facilities in judgments and notices, and on their websites.

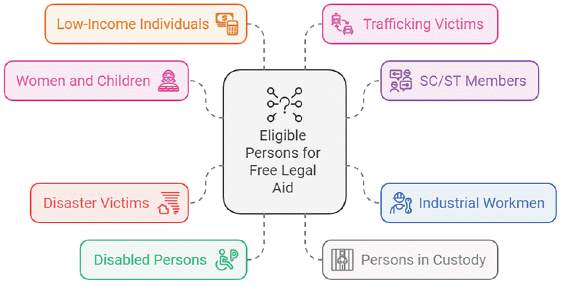

What is Free Legal Aid?

Free Legal Aid refers to providing legal services to individuals who cannot afford to hire a lawyer. It is a crucial aspect of ensuring justice, particularly for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

- Constitutional Right: In India, free legal aid is a right under Article 14 of the Constitution, which ensures justice is provided fairly and equitably. This right is formalized under Section 39A of the Constitution and the Legal Services Authorities Act (LSA Act).

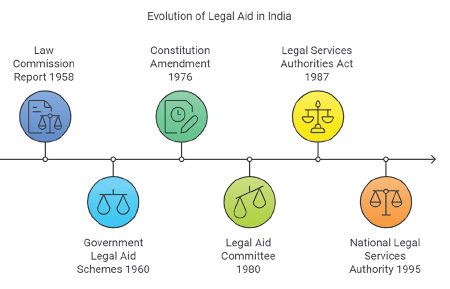

History of Free Legal Aid in India

- Eligibility: Free legal aid is available to individuals who cannot afford to pay for legal services, particularly those belonging to the weaker sections of society.

Legal Provisions Regarding Free Legal Aid

Article 39A: This article, added by the 42nd Amendment to the Constitution, mandates that the State provide free legal aid to ensure that opportunities for securing justice are not denied to any citizen due to economic or other disabilities.

Legal Services Authorities Act (LSA Act), 1987: This Act was enacted to create a framework for providing free legal services to underprivileged citizens. It established the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) to oversee the legal aid system.

- Section 3: Established NALSA.

- Section 4: Outlined NALSA’s functions, including creating policies and schemes to make legal services available, and ensuring funds are allocated to State and District Authorities for implementation.

Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS): This provision ensures that accused individuals in certain cases are provided with free legal aid at the state’s expense if they cannot afford a lawyer.

- Section 341 (1): Allows courts to assign a defence lawyer at the State’s expense when the accused cannot afford one.

Important Judgments Related to Free Legal Aid

Hussainara Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar (1980): The Supreme Court ruled that an accused person who cannot afford a lawyer is entitled to legal aid. It emphasized that a trial without legal assistance for the poor cannot be considered "reasonable, fair, and just."

Madhav Hayawadanrao Hoskot v. State of Maharashtra (1978): The Court recognized the right to legal aid as a fundamental right under Article 21. It clarified that the right to counsel is the State’s duty, not a charitable act by the government. The Court also held that procedural safeguards are essential to protect the liberty of individuals.

These judgments underline the importance of legal aid as a fundamental right and the State's responsibility to ensure that justice is accessible to all, especially the marginalized sections of society.

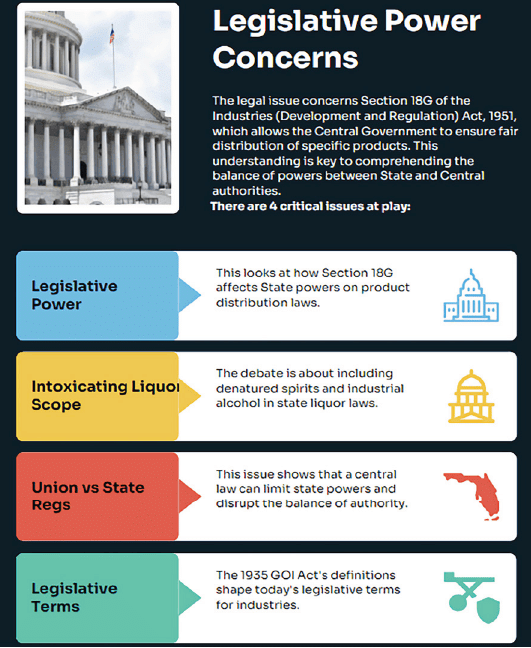

Power of State to Regulate Industrial Alcohol

Why in the News?

A nine-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court delivered an 8:1 ruling affirming that States have the authority to regulate denatured spirit or industrial alcohol, classifying it as “intoxicating liquor” under Entry 8 of the State List. The majority opinion emphasized that the term "intoxicating liquor" should not be narrowly defined and should include substances that could be misused for human consumption. In dissent, Justice Nagarathna contended that industrial alcohol is specifically not intended for human consumption and offered a different interpretation of “intoxicating liquor.”

Background of State of U.P. v. M/S. Lalta Prasad Vaish Case

The case addresses a constitutional dispute between the Union and States over who holds the power to regulate industrial alcohol or denatured spirit. Several constitutional provisions are relevant:

- Entry 8 of List II (State List) grants States control over "intoxicating liquors," allowing them to regulate the production, manufacture, possession, transport, purchase, and sale of alcohol.

- Entry 52 of List I (Union List) gives Parliament authority over industries under Union control.

- Entry 33 of List III (Concurrent List) allows both the State and Union to regulate trade and commerce of products from industries under Union control.

The Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, 1951 (IDRA), enacted by Parliament, governs industries under Entry 52 of List I. Section 18G of the IDRA grants the Central Government powers to regulate the supply and distribution of products from scheduled industries. In 2016, an amendment to the First Schedule of IDRA excluded "potable alcohol" from Union control, while other alcohol remained under its jurisdiction.

In the Synthetics and Chemicals Ltd. v. State of U.P. case, a seven-judge bench addressed Section 18G of the IDRA but did not fully address its impact on State powers. The States argued that "intoxicating liquor" should include denatured spirit and industrial alcohol, asserting their right to regulate all forms of alcohol. The Union maintained that industrial alcohol was distinct from potable alcohol and that Parliament had control over industrial alcohol under IDRA.

The main constitutional issues raised were:

- Whether Entry 52 of List I overrides Entry 8 of List II regarding the regulation of industrial alcohol.

- Whether "intoxicating liquors" in Entry 8 of List II includes alcohol other than potable alcohol.

- Whether a notified order under Section 18G of the IDRA is necessary for Parliament to control industries under Entry 33 of List III.

Court’s Observations

Majority Opinion (8:1)

On Entry 8 of List II (State List):

The Supreme Court held that Entry 8 is both industry-based and product-based, encompassing everything from raw materials to the consumption of “intoxicating liquor.” The Court noted that the phrase “that is to say” in Entry 8 is explanatory, not exhaustive, and the scope includes substances that could be misused for human consumption.On Legislative Competence:

The Court found that Parliament cannot occupy the entire industry field merely by declaring a product under Entry 52 of List I. The State Legislature’s competence under Entry 24 of List II is only limited to the extent covered by Parliamentary law under Entry 52 of List I.On Interpretation of 'Intoxicating Liquor':

The Court ruled that the term “intoxicating liquor” should not be confined to alcoholic beverages that cause intoxication but should include alcohol that could be misused in a harmful manner, impacting public health. The term thus includes:- Rectified spirit

- Extra Neutral Alcohol (ENA)

- Denatured spirit

- Excludes final products with alcohol content, such as hand sanitizers.

On Precedents and Prior Judgments:

The Court overruled the Synthetics (7J) judgment and clarified that the interpretation of “intoxicating liquor” in the First Schedule of the IDRA must be updated to reflect this broader understanding.

Dissenting Opinion (Justice Nagarathna)

On Scope of Entry 8 List II:

Justice Nagarathna argued that Entry 8 exclusively pertains to traditional intoxicating liquors. She contended that industrial alcohol falls outside its purview and should not be considered under this entry based on its misuse potential.On Legislative Intent:

She pointed out that the Constituent Assembly made a clear distinction between potable and non-potable alcohol. “Intoxicating liquors” were intended to represent only a segment of “Fermentation Industries,” and there was no intention to include industrial alcohol within Entry 8.On Regulatory Framework:

Justice Nagarathna stated that denatured alcohol belongs to the category of "industrial alcohol," and Section 18G of the IDRA governs such products under Entry 33(a) List III, which grants Parliament exclusive power to legislate on matters related to scheduled industries under “Fermentation Industries.”

Fundamental Constitutional Framework

Article 246 Distribution Scheme:

- Union List (List I): Grants Parliament exclusive power to legislate.

- State List (List II): Grants States exclusive power to legislate, subject to the Union List and Concurrent List.

- Concurrent List (List III): Both Parliament and States share legislative power.

Parliamentary Powers:

Parliament has exclusive power over List I matters, and in case of irreconcilable conflict with State legislation, its power prevails.State Legislature Powers:

States have exclusive power over List II matters, with limitations only where expressly stated in the Constitution.Interpretation Guidelines:

The Court emphasized the importance of harmonious interpretation between overlapping entries, ensuring that no entry is rendered redundant, and the federal balance is maintained.Conflict Resolution Framework:

The Court ruled that where overlap exists, it should be minimized, and federal supremacy applies only in cases of actual conflict. Courts must strive to interpret legislative entries broadly, avoiding unnecessary conflicts and ensuring that no legislative entry is redundant.

Scope and Significance of Entry 8 of List II

Entry 8 of List II is both an industry-based and product-based entry, covering not just the production of “intoxicating liquor” but also its consumption. The Court held that this entry should be interpreted broadly, encompassing alcohol products beyond traditional alcoholic beverages, including industrial alcohol that may be misused. The use of “that is to say” in Entry 8 is explanatory, signifying a broad scope that includes all alcohol that can potentially be used for intoxication or cause harm to public health. The Court highlighted that Entry 8’s unique status as a specific provision for intoxicating liquors sets it apart from other general entries in the Constitution. Therefore, the States retain regulatory authority over intoxicating liquor, including industrial alcohol, within their jurisdiction, without Parliament overriding their powers through mere legislative declarations under the Union List.

Adhaar Card

Why in News?

The Supreme Court ruled against using the date of birth from an Aadhaar Card to determine the age of a victim in a motor accident compensation case. Instead, the Court stated that the age should be established using the date of birth from a school leave certificate, which holds statutory recognition under the Juvenile Justice Act. This ruling overturned a High Court decision that had reduced the compensation amount based on the Aadhaar Card’s information.

What was the Background of Saroj & Ors. v. IFFCO-TOKIO General Insurance Co. & Ors. Case?

The case concerns a fatal motor accident that occurred on August 4, 2015, in which Silak Ram was riding a motorcycle (registration No. HR-12X-2820) with another person, Rohit. Both were found injured at the roadside.

- Silak Ram succumbed to his injuries, while Rohit was taken to Medical College, Rohtak for treatment.

- Krishan, a passerby, reported the incident to the police.

- Rohit’s statement during the investigation provided details about the offending vehicle, and an FIR (No. 481/2015) was registered under Sections 279/337, 304A of the Indian Penal Code.

On December 16, 2015, the deceased's wife and sons filed a claim petition (No. 25 of 2015) before the Motor Accident Claims Tribunal (MACT), Rohtak. A dispute arose over the deceased’s age:

- The Aadhaar Card indicated the date of birth as January 1, 1969.

- The School Leave Certificate mentioned the date of birth as October 7, 1970.

- Evidence showed that the deceased was an agriculturist owning a tractor and JCB machine.

The case primarily involved determining the correct compensation for the deceased’s family, with the age determination playing a crucial role in calculating the compensation multiplier.

What were the Court’s Observations?

The Supreme Court held that a High Court sitting in appeal should not substitute its view for that of the lower court unless the decision is tainted by perversity, illegality, or serious flaws that render it untenable.

- The Court acknowledged that while the Aadhaar Card can establish identity, it cannot serve as conclusive proof of date of birth, referencing UIDAI’s Circular No. 08 of 2023, which explicitly mentions this limitation.

- The Court gave precedence to the School Leaving Certificate for determining age, citing its statutory recognition under Section 94(2) of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015.

- It found no justification for the High Court’s interference with the MACT’s determination of notional income, particularly since evidence established that the deceased was an agriculturist owning a tractor and JCB machine.

- On interest rates, the Court noted that compensation in MACT cases must be just and reasonable, and increased the interest rate from 6% to 8%.

- The Court also disagreed with the High Court’s reduction of compensation, as there was no evidence to suggest that the rates notified by the District Commissioner, Rohtak, would not apply to the deceased.

- Applying the principles from National Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Pranay Sethi, the Court recalculated the compensation, maintaining a multiplier of 14 based on the deceased’s age of 45 years as per the School Leaving Certificate.

What is an Aadhaar Card?

The Aadhaar card is a unique identification system implemented in India, designed to provide every resident with a distinct identity number linked to their biometric and demographic data.

- The Aadhaar project was initiated by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) in 2009, with the goal of creating a universal identity database for residents of India.

- The Aadhaar number is a 12-digit unique identification number associated with an individual’s biometric data (fingerprints, iris scans) and demographic information such as name, address, and date of birth.

What are the Legal Provisions Involved?

Aadhaar Act, 2016: This Act provides the legal basis for the Aadhaar project. It outlines procedures for enrollment, biometric data collection, and the rights of individuals regarding their data. The Act also mandates Aadhaar for various purposes, including the delivery of subsidies, benefits, and services.

- Establishes UIDAI as a statutory authority.

- Defines the framework for issuing Aadhaar numbers and ensures data protection.

Supreme Court Ruling (2018): In a landmark judgment, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the Aadhaar Act but imposed certain restrictions on its use:

- Aadhaar cannot be made mandatory for services such as school admissions, bank accounts, and mobile connections.

- Aadhaar is mandatory only for filing income tax returns, linking with PAN, and for government subsidies and benefits.

What are the Rights and Responsibilities in Regard to Aadhaar Card?

Individual Rights:

- Voluntary enrollment

- Right to update information

- Right to file complaints

- Access to authentication history

UIDAI Responsibilities:

- Ensure information security

- Maintain authentication records

- Respond to grievances

- Conduct regular security audits

What are the Penalties Imposed?

Criminal Penalties:

- Unauthorized access to the Central Identities Data Repository

- Tampering with data

- Identity theft using Aadhaar

Civil Penalties:

- Non-compliance with regulations

- Unauthorized sharing of data

- Failure to report authentication issues

What is the Implementation Framework Required?

UIDAI Structure:

- A statutory authority under the Ministry of Electronics and IT

- Headquartered in New Delhi with regional offices across India

- Enrollment through authorized agencies

Service Delivery:

- Authentication Services: Yes/No authentication, e-KYC, offline verification

- Update Services: Online demographic updates, biometric updates, mobile number updates

Section 94 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015

Prima Facie Age Assessment:

- The Committee/Board has the authority to make preliminary age determinations based on physical appearance.

- If the person’s age is clearly underage, additional confirmation may not be required.

Tiered Evidence System for Age Verification:

- Primary Documentation: School date of birth certificate, matriculation certificate.

- Secondary Documentation: Birth certificate from municipal authority, panchayat.

- Medical Verification: In cases where other documents are unavailable, ossification tests or medical age determination tests are done.

Legal Presumption:

- The age recorded by the Committee/Board is presumed to be the true age and creates conclusive presumption for the Act’s purposes.

- No provision exists to challenge the age determination once recorded.

Tirupati Laddu Case

Why in News?

The Tirupati Temple ghee controversy erupted after the Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister alleged that animal fat, including beef fat and fish oil, was used in preparing the sacred laddus (prasadam) during the previous YSRCP government’s tenure. The allegations, based on a lab report from the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) in July 2024, sparked public outrage and led to several petitions being filed in the Supreme Court. In response, the Court constituted an independent Special Investigation Team (SIT), replacing the state-appointed SIT, to investigate the sensitive issue that has deeply affected the sentiments of millions of devotees worldwide.

What was the Background of Dr. Subramanian Swamy v. State of Andhra Pradesh and Others?

The controversy surrounding the Tirupati Laddu involves allegations that adulterated ghee was used in the preparation of laddus (prasadam) at the Tirumala Tirupati Temple.

- On September 18, 2024, Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu publicly claimed that animal fat, including beef fat and fish oil, had been used in the laddus during the previous YSRCP government’s tenure, based on a laboratory report from the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) regarding ghee samples.

The Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams (TTD) follows internal quality control procedures:

- Samples are taken from trucks carrying cow ghee upon arrival.

- Material that does not meet the prescribed standards is typically returned to suppliers.

Following the controversy, the Andhra Pradesh government formed a Special Investigation Team (SIT) on September 26, 2024, to look into the matter.

Legal Petitions Filed:

- Dr. Subramanian Swamy’s Petition: Seeks the formation of a court-monitored committee for a thorough investigation, a detailed report on the forensics of the ghee samples, and clarification on the sampling methodology and political interference.

- Suresh Khanderao Chavhanke’s Petition: Calls for an investigation by a committee led by a retired Supreme Court judge or a High Court Chief Justice. He argues that the issue violates the fundamental rights under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution and requests an investigation by the CBI or an independent central agency. He also calls for a retired judge to oversee the temple’s management.

- Surjit Singh Yadav’s Petition: Filed by the President of Hindu Sena, seeking an SIT investigation into the alleged use of animal fat in the prasadam, which he claims hurt the sentiments of Hindu devotees.

- YV Subba Reddy’s Petition: Filed by Rajya Sabha MP and former TTD Chairman, requesting an independent investigation by a court-monitored committee or a retired judge with domain experts. He questions the timing of the state government’s release of the lab report and highlights TTD’s standard operating procedures for ghee testing.

- Dr. Vikram Sampath and Dushyanth Sridhar’s Petition: A joint petition by a historian and a spiritual speaker, seeking the removal of government/bureaucratic control over temples and the establishment of accountability in Hindu temples managed by government bodies.

Key Issues Raised:

- Verification of whether adulterated ghee was used in the preparation of prasadam.

- The timeline of ghee procurement and testing.

- The authenticity and context of the laboratory report.

- Compliance with established quality control procedures.

- Potential violations of religious practices and devotees' rights under Articles 25 and 26 of the Indian Constitution, 1950.

What were the Court’s Observations?

The Supreme Court, recognizing the potential for these allegations to hurt the sentiments of millions of devotees, constituted an independent Special Investigation Team (SIT), replacing the existing state-appointed SIT. The Court emphasized that an independent body would instill greater confidence among the public.

- The Court clarified that its decision should not be seen as a reflection on the credibility of the existing SIT members, stressing that the order was made to address the concerns of devotees and not to question the competence of the state-appointed SIT.

- The bench, consisting of Justices BR Gavai and KV Viswanathan, stated that the Court would not allow itself to be used as a "political battleground" and refrained from commenting on the merits of the allegations and counter-allegations.

- The newly constituted SIT was directed to include two CBI officers (nominated by the CBI Director), two officers from the State Police (nominated by the State Government), and one senior official from the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI). The investigation would be monitored by the CBI Director.

- The Court’s decision followed submissions from various stakeholders, including the Solicitor General of India, who had initially vouched for the competence of the state-appointed SIT but suggested that central monitoring of the investigation would be prudent.

- The bench disposed of several petitions, including those filed by Dr. Subramanian Swamy, ex-TTD Chairman YV Subba Reddy, Suresh Chavhanke, and Dr. Vikram Sampath, addressing the investigation of the alleged use of adulterated ghee in the preparation of prasadam. While the Court did not comment on the merits of the allegations, it clarified that the formation of an independent SIT was intended to reassure the millions of devotees worldwide and should not be construed as a reflection on the credibility of the state-appointed SIT.

What is Article 25 of the Indian Constitution, 1950?

Article 25 deals with the freedom of conscience and the free profession, practice, and propagation of religion:

Freedom of Conscience:

- The right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion.

- It allows individuals to openly declare and follow their religious beliefs.

- It includes the right to carry religious symbols, such as the kirpan in Sikhism.

Right to Practice Religion:

- The right to perform prescribed religious duties, rituals, and exhibits.

Right to Propagate Religion:

- The right to spread one's religious views to others, but it is limited to persuasion and does not include the right to convert others.

Restrictions and Limitations:

- Subject to public order, morality, health, and other provisions in Part III of the Constitution.

- The State can regulate or restrict secular activities associated with religious practices for purposes like social welfare, reform, or opening Hindu religious institutions to all classes of Hindus.

What is Article 26 of the Indian Constitution, 1950?

Article 26 protects the freedom of religious denominations to manage their own affairs:

This right applies to every religious denomination or any section of a denomination.

Religious denominations have the right to:

- Establish and maintain institutions for religious or charitable purposes.

- Manage their affairs in matters of religion.

- Own and acquire both movable and immovable property.

- Administer such property in accordance with the law.

The administration of property must be done within the framework of existing laws, but the article ensures autonomy for religious groups.

Restrictions can be imposed for public order, morality, and health, but the State must respect the internal autonomy of religious groups in managing their institutions and practices.

Provision for Sale of Adulteration in Criminal Law

Section 274 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS): Punishes those who adulterate any food or drink, making it noxious, intending to sell or knowing it is likely to be sold as food or drink. Punishment can be imprisonment for up to six months, a fine of up to ₹5,000, or both.

Section 275 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS): Punishes the sale or exposure for sale of any adulterated or noxious food or drink. The punishment is similar to that under Section 274, with imprisonment up to six months or a fine of up to ₹5,000, or both.

|

63 videos|175 docs|37 tests

|

FAQs on Legal Current Affairs for CLAT (October 2024) - Legal Reasoning for CLAT

| 1. What is Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955 and how does it impact women? |  |

| 2. How does the concept of Right to Free Legal Aid relate to women's rights in India? |  |

| 3. What powers does the state have to regulate industrial alcohol under current laws? |  |

| 4. How has the Aadhar Card impacted the rights of citizens, particularly women? |  |

| 5. What was the significance of the Tirupati Laddu case in terms of legal principles? |  |