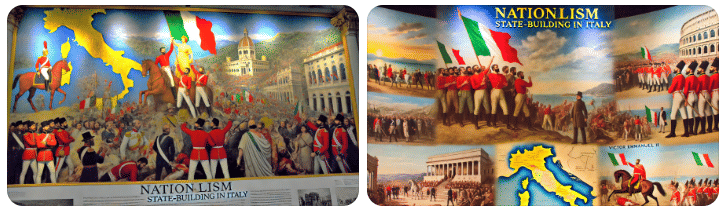

Nationalism: State-building in Italy | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Background

- For centuries, the Italian peninsula was divided into many separate states, making it politically fragmented.

- In 1792, when war erupted between Austria and the Revolutionary French Government, the French invaded the Italian peninsula. They unified many of the Italian states and established them as republics.

- However, in 1799, the Austrian and Russian armies expelled the French from the Italian peninsula, leading to the collapse of these early republics.

French Invasion and Nationalism:

After Napoleon came to power, the French once again conquered the Italian peninsula. Under his rule, the peninsula was divided into three main parts:

Northern Parts:

- The northern regions, including Piedmont, Liguria, Parma, Piacenza, Tuscany, and Rome, were annexed directly into the French Empire.

Newly Created Kingdom of Italy:

- This kingdom comprised areas like Lombardy, Venice, Reggio, Modena, Romagna, and the Marshes.

- It was ruled by Napoleon himself.

Kingdom of Naples:

- Initially governed by Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte, this kingdom eventually passed to Napoleon’s brother-in-law.

- The period of French invasion and occupation had significant impacts on Italy.

- French soldiers and the Napoleonic regime brought new ideas about government and society, revitalizing Italy.

- The French invasion introduced revolutionary concepts that led to the overthrow of old ruling orders and the dismantling of feudal structures.

- Ideas of freedom, equality, and nationalism became prominent, laying the groundwork for Italian nationalism across the peninsula.

- For a brief period, Italians experienced a sense of national unity. However, they felt disheartened when the Congress of Vienna restored the old regime, reversing these changes.

Italy from 1815 to 1850

Reconstitution under Vienna Congress:

- After the defeat of Napoleonic France, the Congress of Vienna was held in 1815 to reshape Europe.

- In Italy, the Congress reinstated the pre-Napoleonic arrangement of independent states, either directly ruled or heavily influenced by major European powers, especially Austria.

- Italy exemplified the principles of legitimacy and balance of power during the Congress.

Division of Italy:

- Italy was divided into eight states.

- Only the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia had an Italian ruler.

Restoration of Rule:

- Hapsburg princes, linked to the Austrian royal family, were reinstalled in Parma, Modena, and Tuscany.

- The Papal States were restored to the Pope.

- Bourbon rule was reestablished in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, formed from the old Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily.

Territorial Changes:

- Genoa was annexed to Piedmont to block the coastal route to France.

- Lombardy and Venice were given to Austria to protect Italy from potential French aggression.

Austrian Dominance:

- Austria became the dominant power in Italy.

- The struggle for Italian unification was primarily against the Austrian Empire and the Hapsburgs, who controlled the northern regions and were the strongest opposition to unification.

Austrian Control:

- Austrian control included the richest provinces Lombardy and Venetia.

- Rulers in Parma, Modena, and Tuscany were placed by Austria.

- The King of Naples was bound by treaty not to implement any government forms unacceptable to Austria.

Suppression of Nationalism:

- Austria suppressed nationalist movements across the Italian Peninsula and in other parts of the Hapsburg Empire.

- Metternich, an influential diplomat, viewed Italy merely as a geographic term, not a nation.

Dependency on Austria:

- Italian states relied on Austria for stability due to their small size.

Literary Influences on Nationalism:

- Literary works contributed to the rise of Italian nationalism.

Proto-Nationalist Literature:

- Manzoni’s The Betrothed, a critique of Austrian rule, was a prominent example of proto-nationalist literature.

Diversity of Political Conditions:

- The varied political conditions and disunion in Italy facilitated Austrian domination.

- Different groups had conflicting views on the nature of a unified Italy.

- Victor Emmanuel I, King of Sardinia-Piedmont, was a staunch supporter of the Old Regime, attempting to restore it by abolishing French laws.

Papal Opposition:

- Pope Pius IX opposed unification efforts, fearing the loss of power and persecution of Italian Catholics.

- Each Italian city’s unique tradition fostered jealousy and rivalry, complicating unification.

Diverse Opinions on Unification:

- Those favoring unification had differing opinions on its structure:

- Some proposed a federation under the Pope, while others envisioned a federal republic or a confederation led by Piedmont.

The Carbonari:

- The Carbonari was a network of secret revolutionary societies in early 19th-century Italy.

- They expressed discontent with the post-1815 repressive regime, especially in southern Italy.

Goals and Ideals:

- The Carbonari aimed for patriotic, liberal, and republican governance.

- While they favored constitutional and representative government, they lacked a unified agenda, with some advocating for a republic and others for a monarchy or federation.

Role in Italian Unification:

- The Carbonari played a significant role in the Risorgimento, particularly in the failed Revolution of 1820.

- Many leaders of the unification movement were former members of this organization.

Insurrection in Naples (1820):

- Inspired by the Spanish revolution over constitutional disputes, the Carbonari incited a revolt in Naples.

- The revolt forced King Ferdinand I to grant a constitution.

Suppression by Austria:

- Austrian intervention was swift, fearing the spread of liberal ideas to Venice and Lombardy.

- Austrian forces suppressed the revolution, restoring King Ferdinand to absolute power.

Aftermath in Naples:

- After the suppression, Ferdinand abolished the constitution and persecuted known revolutionaries systematically.

Insurrection in Piedmont (1821):

- Before the suppression in Naples, Piedmont was in rebellion and Lombardy was also stirring.

- The aim of the 1821 Piedmont revolt was to expel the Austrians and unify Italy under the House of Savoy.

Intervention and Collapse:

- Once again, Austria intervened, and the movement collapsed.

Influence of the July Revolution in France (1830):

- By 1830, the sentiment for a unified Italy resurfaced, leading to a series of insurrections aimed at creating a unified nation.

Revolts and Suppression:

- Revolts occurred in Parma, Modena, and parts of the Papal states but were swiftly suppressed by Austria.

Reasons for Failure:

- The revolts were too localized, and the opposing forces were too strong.

- The general populace was not yet ready for a revolution.

- Initially encouraged by the new French king Louis-Philippe after the July Revolution, he promised intervention in Italy but did not follow through.

Significance:

- Despite its failure, the revolts exposed the weaknesses of reactionary rulers and fueled hatred against the Austrians.

Giuseppe Garibaldi:

- Giuseppe Garibaldi, originally from Nice (then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia), was a disciple of Mazzini and a skilled military leader.

- After participating in an uprising in Piedmont in 1834, Garibaldi was sentenced to death and fled to South America.

Military Exploits in South America:

- Garibaldi gained fame for his military exploits in South America, where he spent fourteen years participating in various wars and learning guerrilla warfare.

Return to Italy (1848):

- Garibaldi returned to Italy in 1848, fighting against the Austrians and later against the French.

- He made a valiant but unsuccessful effort to maintain the Roman Republic of 1849.

Mazzini's Young Italy:

- Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi were two prominent radical figures in the unification movement.

- Mazzini was an Italian nationalist and a fervent advocate of republicanism, envisioning a united, free, and independent Italy.

Young Italy Movement:

- After the repeated failures of isolated insurrections, it became clear that the Carbonari's methods were insufficient for national emancipation.

- Upon his release in 1831, Mazzini organized the Young Italy movement, aimed at promoting republicanism, nationalism, and Italian unification.

Goals and Methods:

- The goal of Young Italy was to create a united Italian republic through widespread insurrection in reactionary states and Austrian-occupied lands.

- Unlike the Carbonari, Young Italy focused on education and insurrection, becoming the nucleus of national revolution.

Dissolution of Carbonari:

- Young Italy superseded the Carbonari as the core of national revolution.

- The movement spread nationalist doctrine, and Mazzini made frequent attempts at uprisings, though these often failed.

Mazzini's Influence:

- Mazzini's contributions to Italian liberation should be assessed by his influence in ideas and inspiration rather than by his failures.

- He instilled moral fervor into the national movement, rekindling enthusiasm and maintaining the spirit of insurrection.

Defining Italian Nationality:

- Mazzini gave a clear shape to the concept of Italian nationality, transforming the cause of a free and united Italy into a popular movement.

Opposition to Communism:

- Mazzini was a strong opponent of Marxism and Communism.

- In 1871, he condemned the socialist revolt in France that led to the short-lived Paris Commune.

- This stance caused Karl Marx to label Mazzini as a “reactionary” and an “old ass.”

Influence and Recognition:

- Mazzini was recognized by Metternich as “the most influential revolutionary in Europe.”

- His ideas influenced figures like Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in India.

Mazzinianism and Political Ideology:

- Mazzini's socio-political thought, referred to as Mazzinianism, and his worldview, the Mazzinian Conception, were later utilized by figures like Benito Mussolini and Fascists such as Giovanni Gentile to describe their political ideology and spiritual conception of life.

Mazzini’s Vision of Italian Nationality and Moral Unity of Mankind

After the downfall of the Carbonari movements and the uprisings of 1830, it was Giuseppe Mazzini who fervently advocated for the cause of Italian unity. He founded the revolutionary society ‘Young Italy’ in 1831, which became the primary platform for educating his fellow countrymen about the importance of national unity.

Mazzini’s Geopolitical Framework

Mazzini’s geopolitical perspective was centered around three core concepts:

- Nation

- People

- Humanity

- He articulated his fundamental ideas in ‘Young Italy’, the society’s newspaper, and further elaborated on them in his numerous writings.

Mazzini’s Conception of Italian Nationality

Mazzini’s vision of Italian nationality was characterized by a triple goal:

- Independence

- Unity

- Liberty(to be achieved through a republic)

- He believed that through the republic, the nation would be formed. By ‘nation’, Mazzini referred to ‘the totality of citizens speaking the same language, associated together with equal political and civil rights in the common aim of bringing the forces of society… progressively to greater perfection’.

For Mazzini, nationalism was intertwined with liberalism, although it had a linguistic basis. He emphasized the importance of language in defining rights, stating:‘As far as this frontier your language is spoken and understood: beyond this you have no rights’.

Mazzini’s Ideal of Moral Unity of Mankind

Mazzini’s vision of Italian nationality was not exclusive; rather, his overarching ideal was the recreation of the moral unity of mankind. He introduced the concept of Threefold Unity:

- Unity of Man: Overcoming the fragmentation of modern individuals in an industrialized society.

- Unity of Nation: Binding all free individuals in a democracy into a community of liberty and equality.

- Unity of Mankind: Ensuring peace and collaboration among all nations.

- Mazzini was also an early advocate of European Unity. He envisioned a “United States of Europe”, seeing European unification as a natural extension of Italian unification.

Young Europe

- After the failure of Young Italy’s revolutionary efforts in Piedmont in 1833, Mazzini established an even more ambitious organization called ‘Young Europe’. This group aimed to forge a pact of fraternity among the youth of various nations to fight for liberty, equality, and fraternity.

- The mission of Young Europe was to “constitute humanity so as to enable it through continuous progress”. Mazzini believed that “every people has its special mission, which will cooperate towards the general mission of Humanity”, and that this mission was encapsulated in its Nationality, which he considered sacred.

- Similar to Young Italy, Young Europe was involved in unsuccessful revolutionary activities. Despite the failures of both societies, they set a precedent that inspired various groups throughout history, from Young Ireland and Young Serbs in the nineteenth century to the Young Turks and Young Chinese in the twentieth century. Mazzini’s concept of the moral unity of mankind, though partially successful, left a lasting impact on future movements.

1848 Revolutions in the Italian States

Problems of the Peasantry:

- In 1848, the hunger and poverty experienced by the lower classes in Italy became a central trigger for revolution, a situation often seen in historical uprisings.

- Due to poor seasonal harvests in 1846 and 1847, many Italians faced hunger along with skyrocketing food prices, leading to numerous demonstrations.

- At the same time, peasants were losing long-held communal lands to the wealthy ruling class, and industrial workers were facing layoffs due to overproduction.

- These combined factors sparked riots and protests in both rural and industrial areas throughout the country.

Reform Movements by Pope Pius IX:

- Pope Pius IX was elected on June 16, 1846, and was seen as a liberal, raising hopes among political liberals and the poor in the Papal States and across Italy.

- He initiated various political and economic reforms, notably pardoning hundreds of political prisoners, which created a significant impact.

- Pope Pius IX established a Council of State to share power, along with a municipal council for Rome and a Citizens’ Guard to arm the middle class in support of his regime.

- These initiatives sparked hopes for increased popular influence in the papal government and for Italian unification.

- In response, Metternich grew uneasy and sent Austrian troops to occupy Ferrara, which provoked strong protests from the Pope and widespread indignation across Italy.

- This sentiment, combined with a strong anti-Austrian feeling, spread throughout Italy in 1847, setting the stage for the revolutionary wave that swept across Europe in 1848, including Italy.

Revolt in Sicily and Naples:

- Inspired by the liberal changes happening in Rome, people in other regions of Italy began to demand similar reforms.

- In Sicily, the populace started calling for a Provisional Government, separate from the mainland's authority.

- King Ferdinand II attempted to resist these changes, but full-scale revolts erupted in Sicily, as well as in Salerno and Naples.

- These uprisings forced Ferdinand and his forces out of Sicily and compelled him to allow the establishment of a provisional government.

- In Sicily, the revolt led to the proclamation of the Kingdom of Sicily, with Ruggero Settimo as Chairman of the independent state until 1849, when the Bourbon army reasserted control over the island on May 15, 1849, by force.

Spread of Revolt in Other Parts of Italy:

- Despite the events in Rome and Naples, many Italian states remained under conservative rule.

- Italians in Lombardo-Veneto were subjected to harsher taxes and tighter control by the Austrian Empire, which stifled any enjoyment of newfound freedoms.

- The revolutionary disturbances began in Lombardy with acts of civil disobedience, such as citizens refraining from smoking and playing the lottery to deny Austria tax revenue.

- In February 1848, relatively peaceful revolts occurred in Tuscany, leading Grand Duke Leopold II to grant Tuscans a constitution. A breakaway republican provisional government emerged in Tuscany shortly after this concession.

- On February 21, Pope Pius IX unexpectedly granted a constitution to the Papal States, surprising many given the Papacy's historical resistance to such changes.

- By the time of the revolution in Paris, all Italian states, except for the Austrian dominion, had constitutions, marking the movement as predominantly democratic with temporary successes in form of constitutional governments.

The Revolt Develops into a Struggle for Italian Liberation:

- The democratic movement gradually transformed into a struggle for national independence.

- Tensions escalated in Lombardy, culminating in revolts in Milan and Venice on March 18, 1848. The insurrection in Milan successfully expelled the Austrian garrison after five days of street fighting.

- The Italian insurgents were bolstered by the news of Metternich's abdication in Vienna and the revolution in Paris. Additionally, Charles Albert of Piedmont had issued a liberal constitution for Piedmont around this time.

- Cavour, a young editor, made a passionate appeal to Charles Albert of Sardinia-Piedmont, urging him to wage war against Austria.

Charles Albert Leads a National War Against Austria and His Defeat:

- Encouraged by the Venetians and Milanese to support their cause, Charles Albert, the King of Sardinia (ruling over Piedmont and Savoy), declared war on Austria, marking the beginning of the First Italian Independence War.

- As he prepared for the attack, Charles Albert garnered support from other princes. Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, sent 8,000 troops, Pope Pius contributed 10,000, and Ferdinand II sent 16,050 men, all under public pressure.

- Despite initial successes, Charles Albert faced a decisive defeat at the Battle of Custoza on July 24. An armistice was reached, and Radetzky regained control over Lombardy-Venetia.

- Following this defeat, Pope Pius IX withdrew his troops, citing his inability to support a war between two Catholic nations. King Ferdinand of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies also recalled his soldiers.

- The monarchs who had reluctantly adopted constitutions in March found themselves at odds with their constitutional ministers.

Aftermath of the Defeat:

- Despite Pius IX's withdrawal from the war against Austria, many of his people continued to fight alongside Charles Albert.

- The people of Rome rebelled against Pius IX's government, leading to the assassination of Rossi, Pius' minister.

- Republican figures like Mazzini and Garibaldi gained popularity as the monarchs fled their capitals, including Pope Pius IX.

- Pope Pius IX sought refuge in the fortress of Gaeta, protected by King Ferdinand II. In February 1849, he was joined by Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who fled due to another insurrection.

- Piedmont fell to Austrian control in 1849, and Charles Albert abdicated in favor of his son, Victor Emmanuel II. A peace treaty was signed on August 6, 1849, forcing Piedmont-Sardinia to pay an indemnity of 65 million francs to Austria.

Republican Movement in Rome:

- Initially, Pope Pius IX embraced reform, but conflicts with revolutionaries led him to abandon the idea of constitutional government. After the assassination of his Minister Rossi in November 1848, Pius IX fled just before Garibaldi and other patriots arrived in Rome.

- In early 1849, elections were held for a Constituent Assembly, which proclaimed a Roman Republic on February 9. Mazzini arrived in Rome in early March and was appointed Chief Minister.

- The Republic inspired people to envision an independent Italian nation. Its Constitution guaranteed religious freedom, abolished the death penalty, and provided free public education.

- The Republic aimed to improve the lives of the underserved by redistributing some Church land to poor peasants and implementing prison and insane asylum reforms.

- It also promoted freedom of the press and secular education but avoided the "Right to Work" policy, having witnessed its failure in France.

- Garibaldi and Mazzini sought to create a "Rome of the People." Tuscany followed Rome's lead and established a republic.

Decline of the Roman Republic:

- The Republic's economy suffered from runaway inflation, and sending troops to defend Piedmont from Austrian forces left Rome vulnerable to attack.

- Pope Pius IX appealed to Napoleon III for assistance. The French President saw this as an opportunity to gain Catholic support and to prevent Austria from having sole control over the situation in Italy.

- The French army arrived by sea and, despite an initial loss to Garibaldi, eventually defeated the Roman Republic with Austrian help.

- On July 12, 1849, Pope Pius IX was escorted back into Rome and ruled under French protection until 1870.

- Louis Napoleon III strengthened his position at home and became a champion of the Catholic religion through this intervention.

Collapse of the Struggle:

- The premature struggle for Italian independence ultimately collapsed, with Austria regaining control over Lombardy and Venetia.

- Absolutism was restored in all states except Piedmont, where Victor Emmanuel II remained loyal to the Constitution granted by his father.

Reasons for the Failure of the 1848 Revolutions in Italy

The 1848 revolutions in Italy were a series of uprisings aimed at achieving national unification and independence from foreign rule, particularly Austrian control. However, these revolutions ultimately failed due to a combination of factors including confusion of aims among the revolutionaries, lack of coordination and leadership, foreign interventions, the Pope's stance, and minimal involvement from the masses.

Confusion of Aims:

The revolutionaries in Italy had divergent goals:

- Giuseppe Mazzini advocated for a republic.

- Vincenzo Gioberti proposed a federation of states under papal leadership.

- Others supported unification under the House of Savoy, the royal family of Piedmont.

The only common ground was the desire to expel Austria.

- Local issues often took precedence, and there was a notable lack of cooperation between different revolutionary factions. For instance, in Piedmont, King Charles Albert was reluctant to accept volunteers from other regions unless they pledged loyalty to him first. This disunity made it easier for conservative leaders like King Ferdinand of Naples to quash uprisings in areas such as Naples and Sicily.

- In Sicily, the revolutionary goals were so distinct that the focus was on independence from Naples rather than national unity. The varying aims and the unwillingness to collaborate among the different states made the failure of the revolutions almost certain.

Lack of Coordination of Efforts:

- The revolutions suffered from a lack of effective leadership. While Mazzini could inspire and Garibaldi could fight, neither had the statesmanship necessary to harness contemporary forces effectively.

- Without a unifying leader, it was nearly impossible for the nationalists to present a united front against the Austrians, leading to the failure of the revolutions.

Among the potential leaders—Pope Pius IX, Mazzini, and Charles Albert—none was universally accepted.

- Charles Albert was defeated twice by Austrian forces, weakening his position as a leader.

- Pope Pius IX, by issuing his allocution, distanced himself from the nationalist cause.

- Mazzini led the Roman Republic for a brief period but was ultimately overpowered by French troops at the Pope's request.

Austrian and French Intervention:

- The revolutionaries in Italy faced significant challenges from foreign military powers, especially Austria.

- Austrian intervention not only suppressed the revolts but also reinstated absolutist rule by restoring previous monarchs. Initially, Austria appeared weakened by revolutions in places like Vienna, and with Metternich's resignation on March 13, 1848, there was a glimmer of hope for Italian revolutionaries. Charles Albert of Piedmont even declared war on Austria, a bold move never attempted before, which sparked optimism.

- However, the Austrians quickly recovered and defeated the Piedmontese forces, notably at the Battle of Custoza on July 24, 1848, under the command of Field Marshal Radetzky. This defeat of Piedmont, considered Italy's strongest state, was a significant blow to the revolutionary cause.

- Despite some initial successes, such as a brief Austrian surrender in Venetia in March 1848, the revolts were ultimately crushed by Austria's formidable military strength. Austria was not the only foreign power involved; France also intervened, deploying troops to restore papal authority in the Papal States after the Pope fled.

The Pope's Refusal to Support the Revolutions:

- Pope Pius IX initially appeared to support liberal reforms, such as releasing political prisoners and ending press censorship. This made him a potential leader for the nationalist movement.

- However, his allocution on April 29, 1848, which condemned the war against Austria and rejected the idea of a unified Italy, alienated him from the nationalist cause. This shift was crucial as it deprived the revolutionaries of a potential leader and ally against Austria.

- After the murder of his chief minister Rossi, Pius IX fled the Papal States, further distancing himself from the nationalists. His appeal to France to suppress the revolts in the Papal States underscored his anti-nationalist stance, contributing significantly to the failure of the revolutions.

Lack of Involvement from the Masses:

- A significant factor in the failure of the revolutions was the lack of mass support. The uprisings were primarily organized by social elites and radicals, with the liberals avoiding popular or peasant involvement, viewing politics as a domain for the middle class.

- The revolutionaries showed little interest in social reform or improving the lives of ordinary people, leading to apathy among the peasantry. This lack of mass support meant that once power was gained, it could not be maintained.

- However, in Sicily, the situation was different. The majority of civilians participated in the uprisings in Palermo due to a cholera outbreak affecting all classes. Despite this mass involvement, Sicily was overwhelmed by King Ferdinand's intense military response.

Significance of the Revolution of 1848:

The 1848 revolutions in Italy, despite their failure, held significant importance.

- Firstly, they marked the first instance of various Italian regions coming together for a common cause, overcoming their narrow provincial interests.

- The war highlighted Sardinia's inability to defeat Austria alone, prompting the need for alliances.

- Ultimately, Sardinia would rely on French (1859) and Prussian (1866) support to expel the Austrians from Northern Italy.

King Charles Albert of Piedmont, despite the failures, emerged as a potential leader for the national cause.

The revolutions simplified the leadership and aim issues: the republican approach was discredited as too radical, and Mazzini's failure in Rome diminished its appeal.

The only viable solution left was the establishment of a Constitutional Kingdom under the King of Sardinia-Piedmont.

Why Piedmont Became the Center of Nationalist Hopes

Piedmont emerged as the center of nationalist hopes due to its wholehearted fight against Austria in 1848-49, despite being one of the biggest losers during the springtime of the people. Although Piedmont's army was defeated, and it lost Lombardy, the future economic powerhouse of Italy, the region underwent significant changes that made it the leader in the unification movement.

Leadership Transition:

- After the defeats, King Carlo Alberto had to abdicate in favor of his son, King Victor Emmanuel II. Fortunately, Victor Emmanuel shared his father’s liberal views, and under his reign, Piedmont retained its liberal constitution despite Austria's pressure.

Political Exiles and Liberal Atmosphere:

- The liberal atmosphere in Piedmont outlasted 1848, partly due to the arrival of numerous political exiles. These exiles contributed to a vibrant political environment that fostered liberal ideas and reforms.

Shift in Nationalist Perception:

- Initially, revolutionists viewed Piedmont as an oppressor similar to Austria. However, the perception shifted as people realized that Italian unity could only be achieved through cooperation with Piedmont. This marked a significant change in priorities from independence and freedom to unification.

Decade of Preparation (1849-1859):

- The period following 1849 until 1859 is referred to as the "decade of preparation." During this time, Piedmont underwent various political and economic reforms, largely attributed to the governance of Count Camillo di Cavour, who became prime minister in 1852.

Cavour's Reforms:

- Cavour believed that economic progress was a result of liberal policies and political stability. His government focused on modernizing Piedmont and weakening the Church, a significant pillar of reactionary forces in Italy.

Economic Modernization:

- Under Cavour's leadership, Piedmont saw substantial advancements in its credit and banking system, foreign investment, and communication infrastructure, including railways. The expansion of railway lines from 8 km to 850 km between 1849 and 1859 is a testament to this rapid development.

Piedmont's Economic Growth vs. Other States:

- Piedmont's swift economic development contrasted sharply with the stagnation of other Italian states, both politically and economically. This stark difference positioned Piedmont as the leader in the unification movement.

Conclusion

Piedmont's transformation from a defeated state to the leader of Italian unification was marked by strong leadership, liberal reforms, and significant economic development. The shift in perception regarding Piedmont's role and the decade of preparation set the stage for the eventual unification of Italy under the House of Savoy.

|

367 videos|995 docs

|

FAQs on Nationalism: State-building in Italy - History Optional for UPSC

| 1. What were the main ideas behind Mazzini's vision of Italian nationality? |  |

| 2. What was the role of the Young Europe movement in the context of Italian nationalism? |  |

| 3. What were the key events of the 1848 revolutions in the Italian states? |  |

| 4. Why did the 1848 revolutions in Italy ultimately fail? |  |

| 5. How did nationalism contribute to state-building in Italy during the 19th century? |  |