Physiographic Regions- 1 | Geography Optional for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Himalayas Formation |

|

| Phases of Himalayas formation |

|

| Indo Gangetic Plains |

|

| Significance of the Plain |

|

Himalayas Formation

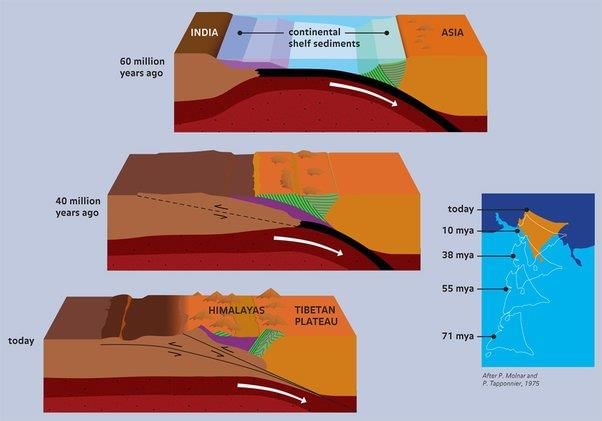

- The Himalayas are the world's youngest mountain range, formed from the geosyncline known as the Tethys Sea through a series of uplifts occurring in various phases. Around 250 million years ago, during the Permian Period, a supercontinent called Pangaea existed. The northern part of Pangaea, called Laurasia or Angaraland or Laurentia, comprised present-day North America and Eurasia (Europe and Asia). The southern part, known as Gondwanaland, consisted of present-day South America, Africa, South India, Australia, and Antarctica.

- A long, narrow, and shallow sea called the Tethys Sea separated Laurasia and Gondwanaland. Numerous rivers flowed into the Tethys Sea, carrying sediments that deposited on the sea floor. As the Indian Plate moved northward, these sediments experienced powerful compression, leading to folding.

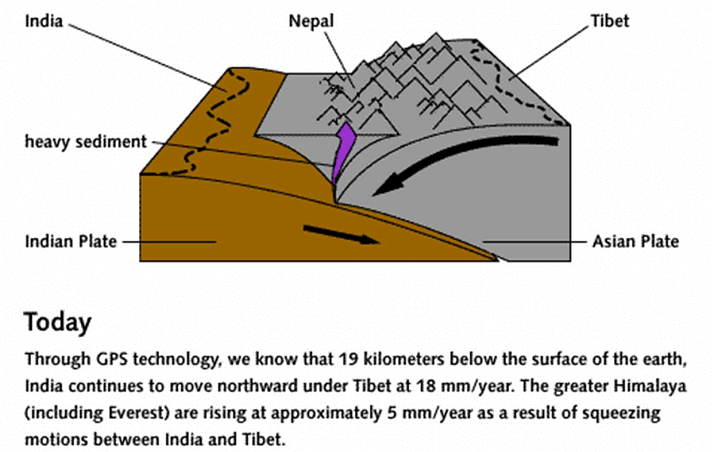

- An example that highlights this process is that Mount Everest's summit is made of marine limestone from the ancient Tethys Sea. As the Indian Plate continued to plunge below the Eurasian Plate, the sediments underwent further folding and elevation, a process that is still ongoing as India moves northward at a rate of about five cm per year, colliding with Asia. The folded sediments, after significant erosional activity, now form the present-day Himalayas.

- The Tibetan Plateau was created due to the upthrusting of the southern block of the Eurasian Plate. The Indo-Gangetic Plain formed as a result of the consolidation of alluvium deposited by rivers flowing from the Himalayas. The Himalayas' curved shape, which is convex towards the south, is attributed to the maximum push provided at the two ends of the Indian Peninsula during its northward drift.

Phases of Himalayas formation

The formation of the Himalayas is a complex process that can be divided into six distinct phases. Rather than being a single mountain range, the Himalayas consist of at least three parallel ranges that have evolved over time from the Tethys Sea, also known as the Himalayan Geosyncline. This gradual process has led to the formation of the majestic mountain range we see today. The following six phases provide a clearer understanding of how the Himalayas were formed.- Phase 1 – 100 million years ago

- Phase 2 – 71 million years ago

- Phase 3 – The Drass volcanic arc

- Phase 4 – Greater Himalayas were raised

- Phase 5 – Rise of lesser Himalayas

- Phase 6 – Rise of the Shiwalik ranges

Phase 1 – 100 million years ago

- During Cretaceous Period, around 100 million years ago, the Indian plate was located b/w 10 ⁰ S – 40 ⁰ S, over the reunion hotspot

- The movement of the plate attained its mass velocity as it was closer to the equator (14cm/yr) and squeezing of the Tethys started towards the end of the Paleocene.

Phase 2 – 71 million years ago

- Himalayan Orogenesis begins roughly about 71 million years ago and the plate with Gondwana continental piece drifted towards North East and the rigid Northwestern flangs composed of the Aravalli series collided with Eurasia.

- The line of collision b/w the Tibetan Plateau and the Indian Plate is called (Indus–Tsangpo Suture Zone) which is a compressional tectonic fault line.

- As the plate began to subduct, crustal doubling below Tibet raised them into a high plateau with a thickness of around 60km

- Along the southern front of the ITSZ ( Indus-Tsangpo Suture Zone), the Murree Foredeep was formed and further south, the Shiwalik foredeep was created.

Orogenesis is the formation of mountains and orogeny is the process by which mountains are formed.

Suture zone is a linear belt of intense deformation, where distinct terranes or tectonic units with different plate tectonic, metamorphic, and paleogeographic histories join together.

Phase 3 – The Drass Volcanic arc

- During Oligocene, the Drass volcanic area was formed and in the Tethys crust, a series of volcanic eruptions took place

- The plate has started anti-clock rotation and Drass became the Pivotal Axis

- Thus, in the western part, pressure and compression were gradually released but towards the East, squeezing of Tethyan sediments has started which marks the beginning of the rising of Tethyan.

Phase 4 – Greater Himalayas were Raised

- The rotation continued and greater compression created a major thrust in the sediments of Murree foredeep and greater Himalayas were raised about 30-35 million years ago (Oligocene to Eocene)

- The compressional thrust line is known as the Main Central Thrust (MCT).

Phase 5 – Rise of Lesser Himalayas

- The sediments were being deposited in the Shiwalik foredeep and further movement in the plate resulted in the rise of lesser Himalayas during the Miocene (15-20 MYA)

- MCT separates greater and lesser Himalayas and the compressional thrust line along which the lesser Himalayas were lifted is called Boundary Thrust/Fault (MBT of MBF) line.

Phase 6 – Rise of the Shiwalik Ranges

- In the Shiwalik foredeep, sedimentation by the Himalayan rivers fills up the molasse material.

- The partial feeding of the Shiwalik foredeep along the Himalayan Frontal Fault( HFF) led to the rise of the Shiwalik ranges which represent partially folded sedimentary range.

- Based on the tecto-geological history, the Himalayan relief and structure can be studied.

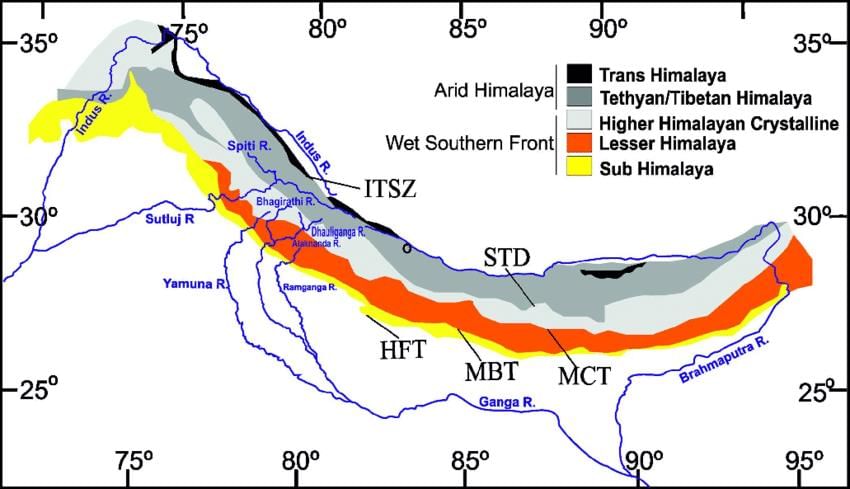

Relief and Structure of Himalayas

- Tibetan Plateau

- Indus –Tsangpo SutureZone

- Tethyan Himalayas

- Greater Himalayas

- MCT

- Lesser Himalayas

- MBF

- Shiwaliks

- HFF

- Indo Gangetic Basin

Tibetan Plateau

- Not a part of Himalayas, but formed due to Himalayan Orogeny

Indus- Tsangpo Suture Zone

- It is a compressional fault line that extends from the Indus gorge to the Tsangpo gorge almost for 3200 km.

- It represents the zone of plate collision where rocks are crushed, pulverized and mostly Paleozoic and ancient rocks are found.

- Presently, river Indus and river Tsangpo flow through the reverse faulted line of discontinuity (Suture – Line where two plates are welding).

Tethyan Himalayas

- The average height is 4000m

- It is compressed with Greater Himalayas and the absence of a longitudinal valley between them manifests the high compressional forces which have sandwiched them

- They have submarine, sedimentary, metamorphic rocks

- They represent initial upliftment in the Tethyan Geosyn or Murree foredeep.

Greater Himalayas

- The average height is 6000m

- Extends from Mt. Namcha Barwa to Nanga Parbat for 2500km

- The mightiest and the most majestic mountain range of the world, boasting of hundreds of peaks rising above 7000m

- High relief, deep gorges, vertical slopes, symmetrical convexity, and antecedent drainage mark the relief feature

- Due to iso-static adjustment and deep cutting of valleys, peaks are sharp and the valleys have escarps or free face.

- They are composed of metamorphic and sedimentary rocks.

- The core of the mountains has Batholith representing the intrusion of Magma (Granitic Magma)

- These mountains have asymmetrical folds due to high compression and they have fractured rocks in the eastern part because of the Indian Plate closed the Tethys like a door slamming shut.

Main Central Thrust (MCT)

- It makes the zone of Tectonic Thrust and the longitudinal axis along which the Greater Himalayas were lifted

- It’s a tectonic compressional valley.

- Rocks are fractured, pulverized and it forms a synclinal basin b/w the Greater Himalayas and the lesser Himalayas

- Kathmandu Valley, Kashmiri Valley, Kulu, and Kangra Valleys are examples of the Syncline basin

- Kulu is a transverse valley while Kangra and Manali are straight valley (These valleys are more prone to earthquakes due to fault beneath).

Lesser Himalayas

Himalayan formation

Himalayan formation

- The average height is 3800m, the length is about 2400kms, almost parallel to the Greater Himalayas but in the Western section, it is segmented into several parallel and transverse ranges

- Parallel Ranges – Pir Panjal, Dhaula Dhar

- Transverse Ranges – Ratan Pir, Nagtiba, Mussourie Range

- The central part in Nepal is called the Mahabharatha range and the eastern part is called the Dafla hills, Mishmi hills, Miri hills, Abor which are closely compressed with the Shiwaliks and difficult to isolate from Shiwalik Ranges

- Here the width of the Himalayas are much less than in the western section and the structure is complex with fracture, fault, pulverization of rocks.

Main Boundary Fault (MBF)

- The Main Boundary Fault (MBF) is a significant fault line in the Himalayas that runs along the longitudinal axis and serves as the location for the second major thrust in the mountain range. However, it is not as deep as the Main Central Thrust (MCT) and is characterized as a compressional fault line.

- While the MCT is known as a low-angle reverse fault, the MBF is a wide-angle reverse fault. As a result, the valleys formed by the MBF are wider, and the rivers that flow through them often create lakes in these valleys. In these lakes, layers of sediment known as Lakestrene sediments are deposited.

- Over time, the rivers managed to cut through the Shiwalik range, eventually developing their course and allowing the Lakestrene sediments to form alluvial plains known as Doons. Examples of these Doons include Dehra Dun and Patli Dun.

- The large longitudinal valleys found between the Lesser Himalayas and Shiwaliks are referred to as "Doons" in the western and central Himalayas, and "Duars" in the eastern Himalayas.

Shiwaliks

- The average height is 800-1200m

- They are partially folded and formed of river sediments deposited in the foredeep

- They represent Hogback topography and the 300m contour line demarcates their boundary with the Gangetic Plain.

- In the western section, it is called Shiwalik

- In Nepal, it is called Churiaghat hills and in Assam, it is called Mishmi, Abor, Dafla, etc (same as in lesser Himalayas)

- Closer to Greater Himalayas in Nepal – Disappear after River Ganges.

Himalayan Frontal Fault (HFF)

- This marks the boundary b/w the Himalayan ranges and the Gangetic basin

- It is a wide-angle thrust line where the last compressional force in the Himalayas Orogeny has taken place.

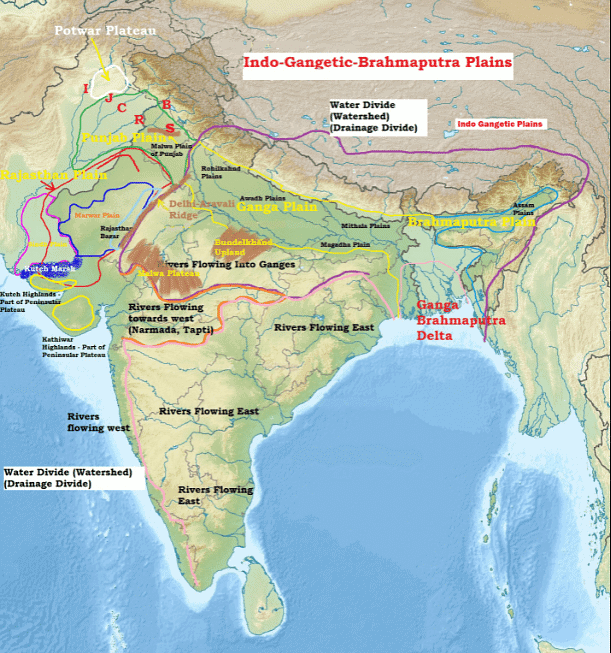

Indo Gangetic Plains

- The Indo-Gangetic Plains are situated between the Himalayas and the Gangetic Basin, with the 300-meter contour line serving as the dividing boundary. To the south, the plains are bordered by the edge of the Indian peninsula, which mostly aligns with the 75-meter contour line, although in the northeastern section, it corresponds with the 35-meter contour line as it approaches the delta.

- These plains are characterized by their extreme flatness, with a gentle slope that varies between 1:1000 and 1:2000. As a result, the landscape of the Indo-Gangetic Plains appears monotonous, consisting of flat and rolling terrain.

Indo gangetic plains

Indo gangetic plains

Formation of Indo–Gangetic–Brahmaputra Plain

- The formation of Indo-Gangetic plain is closely related to the formation of Himalayas.

- The rivers which were previously flowing into the Tethys sea (Before Indian Plate collided with Eurasian Plate – continental drift, plate tectonics) deposited a huge amount of sediments in the Tethys Geosyncline.

- The Himalayas are formed out of these sediments which were uplifted, folded, and compressed due to the northern movement of the Indian Plate.

- The northern movement of the Indian Plate also created a trough to the south of the Himalayas.

Depositional Activity

- During the initial stages of sediment uplift, pre-existing rivers altered their courses numerous times, resulting in their rejuvenation (a state of perpetual youth for the rivers). This rejuvenation process involved intense headward and vertical downcutting of the soft layers above the harder rock stratum.

- Headward erosion refers to the erosion at the beginning of a stream channel, causing the origin to move away from the direction of the streamflow and lengthening the stream channel. Vertical erosion is the downward cutting of a river valley, while lateral erosion occurs at the sides of the river valley. These processes contributed significantly to the production of conglomerates, or mixtures of rock debris, silt, clay, and other materials, which were then carried downslope.

- These conglomerates were deposited in the depression known as the Indo-Gangetic Trough or Indo-Gangetic syncline, which is located between peninsular India and the convergent boundary (the region where the present-day Himalayas are situated). The base of this geosyncline is made up of hard crystalline rock, and it is in this area that the deposited conglomerates accumulated.

New rivers and more alluvium

- The rise of the Himalayas and the formation of glaciers led to the creation of numerous new rivers. These rivers, along with glacial erosion, brought an increased amount of alluvium, which contributed to filling the depression. As more and more sediments, such as conglomerates, accumulated, the Tethys Sea began to recede.

- Over time, the depression was entirely filled with alluvium, gravel, and rock debris, leading to the disappearance of the Tethys Sea and the formation of a flat, featureless plain. This type of plain, known as an aggradational plain, is formed due to the deposition of materials. The Indo-Gangetic Plain is an example of a monotonous aggradational plain that resulted from fluvial deposits.

- Although upper peninsular rivers also played a role in the formation of these plains, their contribution was relatively minor. In more recent times, spanning a few million years, the depositional work of three major river systems - the Indus, the Ganga, and the Brahmaputra - has become more significant. As a result, this curved plain is also referred to as the Indo-Gangetic-Brahmaputra Plain.

Longitudinal Profile – Indo Gangetic Plains

- Bhabhar

- Tarai

- Bangar

- Khadar

Bhabhar Region

- The Bhabhar region is a unique geographical area located adjacent to the Shiwalik foothills. This narrow, porous strip stretches east to west along the foothills and is approximately 8-16 km wide. It extends from the Indus to the Tista rivers, showing a remarkable continuity across the Indo-Gangetic plain.

- The region is characterized by the presence of coarse materials, such as cobbles, pebbles, gravels, boulders, and coarse sand. These materials are found in the form of alluvial fans, which are deposits left by rivers descending from the Himalayas. Over time, these alluvial fans have merged to form the Bhabhar belt.

- One of the most distinctive features of the Bhabhar region is its porosity, which is a result of the extensive deposition of pebbles and rock debris. This porosity causes streams to disappear once they enter the Bhabhar area, leading to dry river courses except during the rainy season.

- The Bhabhar belt varies in width, being narrower in the east and more extensive in the western and north-western hilly regions. It stretches across the Himalayas from Punjab to Assam and has a complex profile with a general slope of 1:6000.

- Due to its porous nature and coarse materials, the Bhabhar region is not well-suited for agriculture. Only large trees with extensive root systems can thrive in this area, as they are able to penetrate the rocky ground and access the water stored below.

Terai Plains

- The Terai Plains, situated in the Bhabhar zone, are characterized by marshy, flat lands with dense deforestation, stretching parallel to the mountains from Punjab to Assam. This region is a narrow, ill-drained, and damp tract found to the south of Bhabar, with its width varying between 15-30 km. The Terai is widest along Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh, and narrowest in the east.

- In the Terai Plains, underground streams from the Bhabar belt re-emerge, making the region more prominent in the east due to the higher amount of rainfall it receives. While most of the area has been deforested for agricultural purposes, the soils of the Terai are rich in nitrogen and humus content.

- A significant portion of the Terai land, particularly in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and Uttarakhand, has been converted into agricultural land, resulting in high yields of crops such as sugarcane, rice, and wheat.

Bangar Region

- The Bangar Region stretches across the entire Gangetic plain, encompassing the older alluvium found along riverbeds. This alluvium forms terraces that are higher than the surrounding flood plains. These terraces often contain calcareous concretions known as 'Kankar.'

- In the deltaic region of Bengal, the Barind plains are a regional variation of the Bhangar, along with the Bhur formations in the middle Ganga and Yamuna Doab. Bhur refers to an elevated piece of land situated along the banks of the Ganga River, particularly in the upper Ganga-Yamuna Doab. These elevated areas have been formed due to the accumulation of wind-blown sands during the hot, dry months of the year.

- Fossils of animals, such as rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, and elephants, can be found in Bhangar. Additionally, it contains Kankar deposits, which are limestone fragments that provide natural supplements of bases to the soil.

- Although the Bhangar Region has been severely degraded in some parts of Uttar Pradesh, where it is referred to as Usar (meaning infertility due to salinization), it generally maintains high levels of fertility.

Barind Tract (Barind Plains)

- The Barind Tract, also known as the Varendra Tract in English and Borendro Bhumi in Bengali, is a large geographical area that dates back to the Pleistocene era and is situated within the Bengal Basin. This region is located in northwestern Bangladesh and north-central West Bengal state in India. The Barind Tract can be found to the northwest of the point where the upper Padma (Ganga) and Jamuna (Brahmaputra) rivers merge. Its borders are defined by the floodplains of the Mahananda River to the west and the Karatoya River to the east, both of which are tributaries of the upper Padma and Jamuna rivers.

- Characterized by its relatively high elevation and undulating landscape, the Barind Tract has distinctive reddish and yellowish clay soils. This region has long been acknowledged as an area consisting of ancient alluvium.

Khadar Region

- The Khadar is composed of newer alluvium and forms the flood plains along the river banks.

- A new layer of alluvium is deposited by river flood almost every year.

- This makes them the most fertile soils of Ganges.

Reh or Kollar

- Reh or Kollar comprises saline efflorescences of drier areas in Haryana.

- Reh areas have spread in recent times with an increase in irrigation (capillary action brings salts to the surface).

Transverse Profile – Indo Gangetic Plains

- Rajasthan Plains

- Punjab Plains

- Gangetic Plain

- Assam Plain (Brahmaputra Plain)

Rajasthan Plain

- The Ghaghar basin in North, Aravallis in East

- It is a part of the Thar desert but it has alluvial deposits of Indus and its tributaries

- In the wake of the Himalayas’ upliftment, these channels shifted to west.

- This plain is an undulating plain (wave-like) whose average elevation is about 325 m above mean sea level.

- 25cm isohyte divides the plain into marusthali in the west and Rajasthan Bagar in the east.

- Marusthali is a desert with shifting sand dunes called Dhrian.

- This entire Marushatli region receives a rainfall of 25cm and the only tree is Khejri (the Bishnoi tribe is associated with it).

- Rajasthan Bagar – It is semi-arid fertile tracts or green patches called ROHI.

- In the north of Luni, a sandy desert is known as THALI.

Saline Lakes

- North of the Luni, there is inland drainage having several saline lakes. They are a source of common salt and many other salts.

- Sambhar, Didwana, Degana, Kuchaman, etc. are some of the important lakes. The largest is the Sambhar lake near Jaipur.

Punjab Plain

- The Punjab Plain is a geographical region formed by the convergence of five major rivers belonging to the Indus River system. These rivers, namely the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas, have created the land between them, known as 'doabs.' As a result, there are five doabs – Chaj, Rechna, Bist, Bari, and Sindsagar – that make up the Punjab Plain.

- The region is characterized by its homogenous appearance, thanks to the depositional processes of the rivers. The name "Punjab" itself means "The Land of Five Waters," referring to the five rivers that shape the area. The total area of the Punjab Plain is approximately 1.75 lakh square kilometers, with an average elevation of about 250 meters above mean sea level.

- The Punjab Plain is extremely fertile, but it also faces issues with poor drainage and a high risk of floods. It is bordered by a 291-meter contour line that runs parallel to the Delhi-Ambala ridge, separating it from the Gangetic Basin. The eastern boundary of the Punjab Haryana Plain is marked by the subsurface Delhi-Aravali ridge.

- In the northern part of the plain, numerous streams called Chos have caused extensive erosion, leading to significant gullying in the region. South of the Satluj River lies the Malwa Plain of Punjab. The area between the Ghaggar and Yamuna rivers is situated in Haryana and is often referred to as the 'Haryana Tract.' This tract serves as a water-divide between the Yamuna and Satluj rivers.

- The Ghaggar River is the only river located between the Yamuna and Satluj, and it is believed to be the modern-day successor of the legendary Saraswati River.

Gangetic Plain

- This is the largest unit of the Great Plain of India stretching from Delhi to Kolkata (about 3.75 lakh sq km).

- The Ganga along with its large number of tributaries originating in the Himalayans have brought large quantities of alluvium from the mountains and deposited it here to build this extensive plain.

- The peninsular rivers such as Chambal, Betwa, Ken, Son, etc. joining the Ganga river system have also contributed to the formation of this plain.

- The general slope of the entire plain is to the east and south east.

- Rivers flow sluggishly in the lower sections of Ganges as a result of which the area is marked by local prominences such as levees, bluffs, oxbow lakes, marshes, ravines, etc. {Fluvial Landforms, Arid Landfroms}

- Almost all the rivers keep on shifting their courses making this area prone to frequent floods. The Kosi river is very notorious in this respect. It has long been called the ‘Sorrow of Bihar’.

Divisions of Ganga plains

- Upper Gangetic Plain

- Middle Gangetic Plain

- Lower Gangetic Plain

Upper Gangetic Plain

- 291m contour in the west, 300m contour in the North, 75m in South and 100m contour in east forms the boundary.

- It includes

- Rohilkhand Plains: Rohila Tribe (Afghan), Bareilly, Muzaffarnagar. It is very fertile. It has Sharda and Ramganga doabs

- Ganga-Yamuna Doab: Largest doab of India. It has fine dust deposits by the aeolian process. It is famous for sugarcane cultivation.

- Yamuna – Chambal Basin: Badland region because of gully erosions, ravines. The worst soil degraded area of India and largest degraded area.

Middle Gangetic Plain

- It is transitional plain par excellence. It is the most fertile tract of the world, which alone can sustain the major population of India.

- It includes 3 sections :

- Awadh Plain: B/w Ghaghra and Gomti, east UP, Flood Prone

- Mithila Plain: B/w Gandak and Kosi, Flood Prone

- Magadh Plain: Located east of R.Son, not flood-prone

- These transitional plains have perfect loam deposits and the groundwater level is very high

Lower Gangetic Plain

- Paradelta in North which is erosion bound looks like an inverted triangle, North part of WB

- Rarh Plains: Western section adjacent to Chota Nagour plateau, Laterite deposits. 35m contour line separates it from Chota Nagar Plateau

- Delta Plains: Most Extensive part of Sunderbans(1/3 in India). The braided channel, lakes, and marshes. It is famous for inland fishing and it is known for Jute cultivation. Sunderbans or Mangrove forests or Tidal Forests are located towards the coastline.

Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta

- This is the largest delta in the world.

- The Ganga river divides itself into several channels in the delta area. The slope of the land here is a mere 2 cm per km. Two-thirds of the area is below 30 m above mean sea level. [Highly vulnerable to sea-level changes]

- The seaward face of the delta is studded with a large number of estuaries, mud flats, mangrove swamps, sandbanks, islands, and forelands.

- A large part of the coastal delta is covered tidal forests. These are called the Sunderbans because of the predominance of the Sundri tree here.

Brahmaputra Plain

- This is also known as the Brahmaputra valley or Assam Valley or Assam Plain as most of the Brahmaputra valley is situated in Assam.

- Its western boundary is formed by the Indo-Bangladesh border as well as the boundary of the lower Ganga Plain. Its eastern boundary is formed by Purvanchal hills.

- It is an aggradational plain built up by the depositional work of the Brahmaputra and its tributaries.

- The innumerable tributaries of the Brahmaputra river coming from the north form a number of alluvial fans. Consequently, the tributaries branch out in many channels giving birth to river meandering leading to the formation of the bill and ox-bow lakes.

- There are large marshy tracts in this area. The alluvial fans formed by the coarse alluvial debris have led to the formation of terai or semi-terai conditions.

Significance of the Plain

- The significance of the Plain region in India lies in its ability to support a large population, foster agricultural development, and facilitate industrialization and urbanization.

- Covering one-fourth of India's land area, the Plain region is home to half of the country's population. This is mainly due to the fertile alluvial soil, flat landscape, slow-moving perennial rivers, and favorable climate, which enable intensive agricultural activities. The widespread use of irrigation in Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh has led to these areas becoming the granary of India, similar to how the Prairies are considered the granaries of the world.

- Apart from the Thar Desert, the entire Plain region is well-connected by a dense network of roads and railways, which has spurred large-scale industrialization and urbanization. This has resulted in increased economic growth and development in the region.

- In addition to its economic significance, the Plain region holds great cultural and religious importance. Many sacred sites and religious places are situated along the banks of the holy rivers Ganga and Yamuna, which are revered by Hindus. The Plain region has also been the cradle of several religious and spiritual movements, including Buddhism, Jainism, Bhakti, and Sufism. Consequently, the area attracts a large number of tourists, boosting the cultural tourism industry.

In summary, the Plain region in India plays a vital role in supporting the country's population, agriculture, industrialization, and urbanization. Furthermore, its cultural and religious significance contributes to India's rich heritage and attracts tourists from around the world.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the formation of the Himalayas and the Indo-Gangetic-Brahmaputra Plain is a result of complex geological processes involving the movement of the Indian Plate, the closure of the Tethys Sea, and the upliftment and folding of the sediments in various phases. The Himalayas, consisting of three parallel ranges, continue to evolve as the Indian Plate moves northward. The Indo-Gangetic-Brahmaputra Plain, formed due to the deposition of alluvium by the rivers originating from the Himalayas and peninsular India, is an agriculturally fertile region with a diverse landscape including Bhabhar, Terai, Bangar, and Khadar regions. The formation of these majestic mountain ranges and fertile plains not only highlights the immense geological forces at work but also showcases the intricate interconnections between geological processes, climate, and human life.

|

304 videos|718 docs|259 tests

|

FAQs on Physiographic Regions- 1 - Geography Optional for UPSC

| 1. What are the main phases of the Himalayas formation? |  |

| 2. What is the relief and structure of the Himalayas? |  |

| 3. What are the characteristics of the Indo-Gangetic Plains? |  |

| 4. What is the significance of the Indo-Gangetic Plain in India? |  |

| 5. How does the formation of the Himalayas affect the climate of the surrounding regions? |  |