The Transition to Food Production: Neolithic– Chalcolithic, and Chalcolithic Villages - 3 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

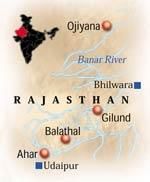

| Ahar Culture Sites in Rajasthan |

|

| Middle Ganga Plain and Eastern India |

|

| Neolithic Sites in the Middle Ganga Plain |

|

| The Life of Early Farmers |

|

| Changes in Cultic and Belief Systems |

|

Ahar Culture Sites in Rajasthan

- Ahar : Early iron artifacts like an iron ring, nail, arrowhead, chisel, peg, and socket suggest one of the earliest instances of iron use in the subcontinent, although there is debate about whether the levels they were found in were intact or disturbed.

- Gilund : Similar to Ahar, with discoveries including a mud-brick complex, burnt brick wall on stone rubble foundation, storage pits, microliths, copper fragments, semiprecious stone beads, terracotta gamesmen, and animal figurines, notably humped bulls with long horns.

- Balathal : Period I : Early phase featured small circular wattle-and-daub huts with mud-plastered floors and storage pits. Later phase revealed a massive mud fortification wall with stone reinforcement and bastions, enclosing over 500 sq m, with walls 4.80 m to 5.0 m wide. A north-west to south-east street and a small lane were also uncovered. Period I (Second Phase) : Larger rectangular houses made of mud, mud-bricks, and stone on stone foundations. Discovery of multi-roomed complexes with kitchens and storage areas, along with two potters’ kilns.

- Pottery and Artifacts : Diverse pottery types including thin red, tan, black-and-red, and buff-coloured pots. Reserve slip ware featuring intricate designs made with a comb-like instrument. Coarse wares such as red-slipped, plain red, burnished grey, and plain grey ware. Copper tools like choppers, knives, razors, chisels, and barbed and tanged arrowheads. Bone tools including points and scrapers, stone querns, grinders, and hammer stones, terracotta balls, and stylized figurines of bulls and sheep. Ornaments made of terracotta, steatite, faience, and semiprecious stones like carnelian, agate, and jasper, along with copper, shell, and terracotta bangles.

- At the archaeological site of Balathal, a large number of animal bones were discovered, including those from gaur, nilgai, chausingha, blackbuck, fowl, peafowl, turtle, fish, and molluscan shells. However, wild animals made up only 5 percent of the bones found. The majority of the bones belonged to domesticated animals such as cattle, buffalo, sheep, goat, and pig, with cattle bones constituting nearly 73 percent of the faunal remains.

- The plant remains found at the site included wheat, barley, at least two varieties of millet, black gram, green gram (moong), pea, linseed, and fruits like jujube (ber). It appears that cereals and lentils were grown in large quantities and stored in storage bins, several of which have been uncovered. Grain was processed into flour using stone querns, and bread was likely cooked on handmade flat pans (tawas) on U-shaped chulhas, similar to those used in present-day villages.

- Calibrated dates suggest that the protohistoric settlement at Balathal dates back to the late 4th millennium BCE, making it contemporary with the early Harappan phase at Kot Diji and possibly as early as the Jodhpura–Ganeshwar culture in northeastern Rajasthan.

- Sites associated with the Ahar culture exhibit the use of a wide range of raw materials, including steatite, shell, agate, jasper, carnelian, lapis lazuli, copper, and bronze. While the shell objects were made locally, the shell material likely originated from the Gujarat coast. The discovery of etched carnelian beads, a lapis lazuli bead, and Rangpur-type lustrous red ware in Ahar Period IC indicates a connection with Harappan sites in Gujarat.

Malwa Region

Kayatha Culture

- Pottery: Found three types of pottery at Kayatha culture sites.

- Kayatha Pottery: Fine, sturdy, wheel-made ware with thick brown slip and linear designs in violet or deep red. Typical shapes include bowls, basins, vases, and large storage jars.

- Buff Ware: Thin, fine fabric with red-painted linear and geometric designs. Shapes include lotas, jars, and basins.

- Red Combed Ware: Fine fabric decorated with wavy and zigzag lines. Shapes consist of bowls and basins.

- House Construction: Houses were likely made of mud and reed with mud-plastered floors.

- Domesticated Animals: Bones of domesticated cattle and horses were found, suggesting these animals were part of the household.

- Diet: Evidence of tortoise consumption, but no grain remains were identified.

- Stone and Copper Artifacts: Rich variety of stone and copper artifacts found. Stone tools included microliths made of locally available chalcedony. Copper technology was advanced, with tools like axes, chisels, and bangles.

- Jewelry: Beautiful necklaces made of agate and carnelian beads, along with steatite micro-beads found in pots.

- Sudden Abandonment: Evidence suggests inhabitants left suddenly, abandoning valuable possessions.

Ahar Culture

- Pottery: Characterized by thin-walled, well-made painted pottery with red designs on a cream or red slip background. Some pottery featured intricate black designs.

- House Construction: Houses were made of mud with reed matting, and mud-plastered floors.

- Domesticated Animals: Evidence of domesticated cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs.

- Diet: Remains of wheat, barley, and rice found, indicating a diverse agricultural diet.

- Stone and Copper Artifacts: Tools made of stone, copper, and bronze, including grinding stones, chisels, and axes.

- Jewelry: Various ornaments made of terracotta, bone, and shell, including beads and pendants.

- Trade: Evidence of trade with distant regions, as indicated by the presence of marine shells and exotic stones.

Malwa Culture

- Pottery: Similar to Ahar culture with variations in design and quality.

- House Construction: Continued use of mud and reed for house construction with improvements in design.

- Domesticated Animals: Similar to Ahar culture with the addition of horses.

- Diet: Expansion of agricultural practices to include pulses and millets.

- Stone and Copper Artifacts: Increased variety of tools and ornaments, with advances in metallurgy.

- Jewelry: More complex designs and materials, including glass and semi-precious stones.

- Trade: Expanded trade networks, as indicated by the presence of foreign goods.

Kayatha and Its Connections

- Kayatha ware shows similarities to early Harappan pottery, suggesting a connection between the two cultures.

- There is also a resemblance between the steatite micro-beads found in Kayatha and those from the Harappan culture.

- The axes discovered at Kayatha have indentation marks similar to those found on specimens from Ganeshwar, indicating a possible link between these sites.

- Despite these connections, the precise nature of the relationship between Kayatha and Ganeshwar is difficult to determine.

Ahar/Banas Culture Phase

- Around 1800 BCE, there was an abrupt break in occupation at Kayatha, and the site remained deserted for about a century.

- When Kayatha was reoccupied, it represented a phase of the Ahar/Banas culture, indicating a shift in the cultural practices at the site.

The Western Deccan

Savalda Culture

- The Savalda culture is considered the earliest farming culture in the western Deccan, dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE.

- This culture is named after the site of Savalda in the Tapi valley, with sites found between the Tapi and Godavari rivers in north Maharashtra.

- Typical Savalda ware includes wheel-made chocolate-coloured pottery with a thick, crackled slip.

- Common shapes of Savalda pottery include high-necked jars, dishes, bowls, basins, vases, and beakers.

- Notable features of Savalda pottery include painted designs of tools, weapons, and geometric motifs over the slip.

Kaothe Site

- Kaothe is a site associated with the Savalda culture, covering an area of 20 hectares.

- The shallow 50 cm thick deposit at Kaothe suggests a short-duration, nomadic occupation.

- Houses at Kaothe were likely round or oval with sloping roofs.

- Numerous bone tools and beads made of shell, opal, carnelian, and terracotta were found at the site.

- Animal bones identified include those of wild deer, domesticated cattle, buffalo, sheep/goat, and dog.

- Plant remains consisted of various millets and pulses such as gram and moong.

- The pottery from Kaothe included sturdy wares with geometric and naturalistic designs.

Daimabad Site

- Daimabad, located on the banks of the Pravara river in Ahmednagar district of Maharashtra, also exhibits a Savalda culture phase.

- Evidence from Daimabad suggests a non-semi-nomadic community with mud houses, some large and multi-roomed, featuring hearths, storage pits, and jars.

- Some houses had courtyards, and a lane was traced in one area of the site.

- Excavations at Daimabad yielded microliths, bone and stone artefacts, and beads made of shell, carnelian, steatite, and terracotta.

- A notable find was a phallus-shaped object made of agate found inside a house.

- Plant remains from Daimabad included wheat, barley, pea, lentil, black gram, and green gram.

Middle Ganga Plain and Eastern India

Archaeological discoveries in eastern India, particularly in the Middle Ganga Plain and parts of Bihar, reveal a rich history of early food-producing settlements and agricultural communities. These findings span from the Neolithic period to the medieval era, showcasing the evolution of human societies in this fertile region.

1. Early Settlements in the Middle Ganga Plain

- Initially, evidence of early food-producing settlements was found in the northern Vindhyan fringes and the Middle Ganga Valley, including sites like Koldihwa, Mahagara, Kunjhun, and Lahuradeva.

- Sohagaura, located in the Sarayupara plain of northeastern Uttar Pradesh, is a key site within the Middle Ganga Plain. This area is bordered by the Ghaghara River to the south and west, the Gandak River to the east, and extends up to the Himalayan foothills.

- Excavations at Sohagaura, conducted in the 1960s and 1970s, revealed a six-fold cultural sequence ranging from the Neolithic period to the medieval era.

- During the Neolithic period (Period I), evidence included handmade pottery with coarse or medium fabric, often rusticated or cord impressed.

2. Neolithic and Neolithic-Chalcolithic Sites in North Bihar

- Several Neolithic and Neolithic-Chalcolithic sites have been identified in the alluvial plains of north Bihar, indicating the presence of agricultural villages along riverbanks during the 3rd/2nd millennium BCE.

- Excavated sites such as Chirand, Senuar, Chechar-Kutubpur, Maner, and Taradih demonstrate the establishment of full-fledged agricultural communities in the Gangetic plains of Bihar.

- Chirand, located at the confluence of the Sarayu and Ganga rivers, features a large mound with a thick occupational deposit dating back to the mid-3rd millennium BCE or earlier.

- Various tools made from quartzite, basalt, and granite, including stone celts and hammer stones, as well as pestles, querns, and balls, were discovered. Microlithic blades and points made from materials like chalcedony, chert, agate, and jasper were also found.

- A significant number of bone and antler implements, such as celts, scrapers, chisels, hammers, needles, points, borers, awls, diggers, and pins, were unearthed. Bone ornaments, including pendants, earrings, bangles, discs, and combs, as well as bangles made from tortoise bone and ivory, were present.

3. Pottery and Ornaments

- The pottery from Neolithic Chirand included red, grey, and black wares, with some examples of black-and-red ware. Most pottery was handmade, although some exhibited turntable techniques.

- Decorative elements such as painted and scratched designs, usually in red ochre, were common, along with burnished exteriors on grey pots. Various shapes of vases and bowls were produced.

- An array of beads made from agate, carnelian, jasper, and marble was also discovered.

Neolithic Sites in the Middle Ganga Plain

Chirand

- Site known for its early agricultural community.

- Excavations revealed various terracotta artifacts such as beads, bangles, wheels, and figurines of animals.

- Evidence of food production with remains of rice, wheat, barley, and lentils, along with animal bones indicating hunting and fishing.

- The presence of burnt clay chunks with impressions suggests houses were destroyed by fire.

- Later, chalcolithic occupation levels were also found.

Chechar-Kutubpur

- Located across the Ganga river from Patna, this site showed changes in pottery over three phases of Neolithic occupation.

- People lived in circular huts with mud floors and central hearths.

- Numerous tools made of bone and antler, along with micro-beads of steatite and chalcedony, were discovered.

Senuar (Ancient Mound)

- Situated on the banks of the Kudra river in Bihar, this site has four periods of occupation ranging from Neolithic to early centuries CE.

- Period I, which includes Neolithic and Chalcolithic phases, showed evidence of early agricultural practices and was dated through radiocarbon methods.

- The lower levels of Period I were dated to around 1770–1400 BCE, indicating early agricultural activities in the region.

Senuar: Period IA

- Neolithic Deposit: At Senuar, Period IA revealed a 1.5-meter-thick neolithic deposit featuring remnants of wattle-and-daub houses.

- Pottery Varieties: Three main types of pottery were identified: red ware, burnished red ware, and burnished grey ware. Some pottery was rusticated, while others had designs created by cord impressions. Common shapes included wide-mouthed shallow bowls, channelled bowls, vases, and spouted vessels. Most pottery was wheel-made, though some were handmade.

- Lithic Tools: Numerous microliths, flakes, and blades made from materials like chert, chalcedony, agate, quartz, and quartzite were discovered. Additionally, triangular polished celts, stone pestles, saddle querns, hammer stones, and sling balls of various sizes were found.

- Bone Tools: Bone tools, including points with wear marks at the tips, were also part of the assemblage.

- Beads: Beads made from semi-precious stones were among the findings.

- Animal Remains: The analysis of animal bones indicated the presence of domesticated animals such as cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, pigs, cats, and dogs. Wild animals identified included nilgai, antelope, and chital. The presence of charring and cut marks on many bones suggested that these animals were processed for food. Evidence of shellfish consumption was found through remains of molluscs and a large number of shells. Interestingly, despite the site’s riverbank location, no fish bones were reported.

- Agricultural Evidence: Carbonized grains indicated that people cultivated two crops a year, with rice (Oryza sativa) being the primary crop. Other crops included barley, dwarf wheat (Triticum sphaerococcum), sorghum millet, ragi millet, lentils, grass peas (Lathyrus sativus), and field peas (Pisum arvense).

Senuar: Period IB

- Neolithic-Chalcolithic Deposit: Period IB at Senuar consisted of a 2.02-meter-thick deposit. House floors were constructed of well-rammed earth mixed with kankar and potsherds, with visible post-hole marks in some areas.

- Copper and Lead Objects: Nineteen copper objects were discovered, including a fishhook, wire, rings, a broken needle, and several fragmented or unidentified items. A fragmentary lead rod was also found. Chemical analysis of the copper wire indicated it was made of nearly pure copper, likely sourced from the nearby Rakha mines.

- Artefact Comparison: Artefacts from Period IB were similar to those from Period IA, but pottery showed significant improvement, especially in surface treatment. While most pots were wheel-made, some handmade pieces were present. Vessels featured fine slips and high-quality burnishing.

- Pottery Decoration: Post-firing red ochre paintings, previously found only on burnished grey ware, were now also seen on burnished red ware. Painted decorations became more frequent, with pots often adorned with thumb or finger impressions, rope, or notched patterns on appliqué bands of clay.

- During Period IB, there was an increase in the number of stone tools compared to the earlier phase, including many polished stone celts primarily made of black basalt. Microliths were also found in large quantities. The materials used for the tools were similar to those in Period IA, but there were a few new shapes introduced. Shell ornaments included triangular pendants, and there were many finished and unfinished beads made from semi-precious stones such as agate, carnelian, and jasper.

- Additionally, twenty-five faience beads were discovered. Terracotta artefacts consisted of beads, pottery discs, a bull figurine, and possibly a whistle. Some pottery discs may have been used as wheels for toys or gaming counters for children, while those with holes might represent spindle whorls. In Period IB, along with the grains from Period I, there were new plant remains including bread wheat, chickpea or gram, and moong. There were also cultural similarities observed between neolithic Chirand and Senuar.

- The site of Maner, located near Patna along an old course of the Ganga, revealed a neolithic deposit 3.45 m thick containing handmade red ware and burnished red and grey wares. The pottery included long-necked vases, bowls with short stems, lipped bowls, and spouted bowls. Other artefacts found at Maner included stone microliths, bone points, and terracotta spindle whorls.

- Taradih, situated near the Mahabodhi temple at Bodh Gaya, showed two phases of neolithic occupation. Period IA featured hand-made burnished and un-burnished red wares and cord-impressed wares, while Period IB saw the emergence of handmade burnished grey ware, sometimes adorned with post-firing ochre painting. Other artefacts from Taradih included neolithic celts, microliths, and bone tools. Remains of wattle-and-daub houses with hearths were discovered, along with bones of various animals such as cattle, goat, buffalo, pig, sheep, deer, bird, fish, and snail.

- Plant remains included grains of rice, wheat, and barley. Neolithic tools like ring stones, shouldered celts, and triangular and rectangular axes have been found in different parts of West Bengal, although the dating of these finds remains uncertain. Kuchai, an excavated site in Orissa, yielded faceted hoes, chisels, pounders, mace heads, and grinding stones, along with reddish-brown pottery tempered with coarse grit, some featuring slips and incised decorations. Neolithic materials such as faceted and shouldered celts, bar chisels, rounded butt axes, wedges, and hammer stones have been found on the surface in Mayurbhanj district, but there is ambiguity regarding their dates and cultural contexts.

Celts from Nayapur and Kuchai; Shouldered Celt from Kuchai

- The north-eastern states of India, including Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and Manipur, have not been thoroughly investigated for prehistoric sites. Numerous polished stone tools have been discovered in different areas of the Khasi, Garo, Naga, and Cachar hills, but their cultural significance and dating remain unclear.

- It's important to note that polished celts have been found at historical levels in certain locations. Excavations have taken place at sites such as Sarutaru, Daojali Hading, and Marakdola in Assam. These sites will be examined in Chapter 5, as the neolithic layers here may be relatively recent.

Southern Neolithic Sites

- The southern neolithic sites are generally dated to the period between c. 2900 and 1000 BCE. However, they can be further categorized based on their chronological and geographical contexts. The earliest dates, ranging from c. 2900 to 2400 BCE, have been established for sites such as Utnur, Pallavoy, Kodekal, and Watgal. This section focuses on these early sites, while the discussion of later ones will be reserved for Chapter 5.

- The previous chapter covered the extensive paleolithic and mesolithic occupation in peninsular India. Currently, there is limited information regarding the dating of the mesolithic phase in the far southern region, and the relationship between the mesolithic and neolithic phases has not been adequately explored.

- It is peculiar that there is scant evidence of neolithic sites along the south-eastern coast of India, given that this region has produced palaeolithic and mesolithic artefacts. Apart from a neolithic site in Pondicherry on the Tamil Nadu coast, there is a noticeable absence of sites in the deltas of the Pennar, Krishna, and Godavari rivers. This absence may be attributed to sites being covered by riverine silt or insufficient exploration. Nonetheless, there are numerous sites in the middle and lower Krishna valley.

- In the southern part of the Deccan plateau, where granite hills emerge from the black cotton soil, the earliest neolithic villages were typically situated on hillsides and plateaux, occasionally near minor streams and, less frequently, along the banks of major rivers. A characteristic feature of many sites in this region is the presence of ash mounds. Research on the southern neolithic has largely centered around the study of these ash mounds. The two primary areas of interest are the Raichur doab, located between the Krishna and Tungabhadra rivers, and the Shorapur doab, situated between the Bhima and Krishna rivers. Excavations of ash mounds have been conducted at sites such as Utnur, Kupgal, Kodekal, and Pallavoy.

Ash Mound Sites

- Ash mound sites are large piles of ash and melted material formed by the repeated burning of cow dung. These sites indicate the presence of neolithic cattle pens surrounded by strong enclosures made of tree trunks. Even today, cattle breeders in parts of central and South India use similar enclosures for their animals.

- Some neolithic pens were connected to permanent settlements, while others might have been temporary camps. The regular burning of dung heaps could be linked to seasonal festivals marking the start or end of annual migrations to forest grazing areas. In peninsular India today, pastoralists still light bonfires on such occasions, and it is believed that driving cattle through fire protects them from diseases.

- Excavations at Utnur, located in the Mahbubnagar district of Andhra Pradesh, revealed that the wooden enclosure of the cattle pen was rebuilt multiple times, and the dung inside was burned repeatedly. Cattle hoof prints were discovered in the ash, indicating the presence of cattle. The size of the enclosure suggested it could accommodate around 540 to 800 cattle.

- Utnur also provided evidence of a small number of ground stone axes, stone blades, and handmade coarse pottery. This pottery included burnished grey or buff ware, which was usually plain but sometimes featured post-firing designs painted in red ochre. Additionally, there was ware with a red, black, or brown dressing applied before burnishing and firing, sometimes adorned with pre-firing black or purple painted designs. The material culture found at Utnur was similar to that of other sites like Piklihal, dated around 2100 BCE, and Kodekal.

Further Discussion

The Mystery of the Ash Mounds

- The ash mounds, initially reported in the 1830s and 1840s, were thought to be of volcanic or limestone origin and were called ‘cinder mounds’ or ‘cinder camps.’ T. J. Newbold’s excavation at Kupgal, where he found pottery, animal bones, and a rubbing stone, suggested these mounds were human-made, not natural.

- Robert Bruce Foote later linked the mounds to neolithic culture, proposing they were burnt cow dung heaps created by neolithic cattle herders. His findings at Budikanama and chemical analysis of ash mound material supported this idea.

- However, Foote’s theory faced skepticism. Robert Sewell believed some mounds dated to the medieval period, while G. Yazdani and others speculated they were linked to metal workers or iron-smelting activities.

- In the 1950s, researchers Raymond Allchin and F. E. Zeuner advanced the understanding of ash mounds. Zeuner’s chemical and microscopic analysis of ash from Kudatini confirmed it was dung, likely cattle dung. Allchin’s archaeological survey in the Raichur doab, especially at Utnur, connected ash mounds with cattle pens, supporting Foote’s theory. Their work revealed that cattle dung was burnt multiple times deliberately, not by accident.

- Remaining questions include whether dung was burnt in situ or collected and heaped up, the reasons for regular burning, and potential symbolic significance. Allchin proposed these ash fires might represent annual seasonal rituals of purification.

- Another issue that needs to be addressed is the connection between ash mounds and settlements. Allchin proposed that there are two types of ash mounds:

- Ash mounds near permanent settlements, like Kupgal and Gadiganur.

- Ash mounds not linked to any settlements, including some of the largest ones, like Kudatini and Utnur.

- However, based on his excavations at Budihal, K. Paddayya argued that ash mounds and habitation areas are not different types of sites but are actually connected. He also believed that ash mounds were not formed by burning dung on site, but rather by piling up dung and garbage cleared from pens and houses and then burning it.

- It's important to note that ash mounds are not found at all southern Neolithic sites. For example, in the Pennar basin of Cuddapah district in Andhra Pradesh, there are Neolithic sites without ash mounds. The same is true for sites in the upper Tungabhadra valley and southern Karnataka.

- P. C. Venkatasubbaiah suggested that the absence of ash mounds in the Cuddapah district could be due to differences in subsistence systems. In this area, people engaged in animal breeding but also relied on farming millet and pulses. Because agriculture was important, cow dung was used as manure instead of being burned for ceremonial or other purposes.

- Another possibility is that even if agriculture was practiced at many southern Neolithic sites (and there is increasing evidence to support this), manuring may not have been necessary. In such cases, dung and dung ash could have been used for plastering houses, but they did not hold the same value as resources do for villagers today. The reasons for the presence or absence of ash mounds at southern Neolithic sites may be more related to differences in cultural traditions rather than subsistence practices.

- The relative dating of ash mound and non-ash mound sites is still not fully understood, and further investigations are needed. It is likely that not all ash mound sites represent the same type of settlement pattern.

- Recent excavations at Watgal and Budihal employed new archaeological methods and techniques, with a particular focus on the meticulous collection and analysis of animal and plant remains. Watgal, situated in the Raichur district of north Karnataka, yielded its earliest calibrated radiocarbon date ranging from 2900 to 2600 BCE, indicating continuous occupation into the 1st millennium BCE.

- Period I at this site featured a microlithic industry primarily consisting of blades and lunates crafted from chert and quartzite, along with substantial flakes of basalt and dolerite.

Watgal

Period IIA (c. 2700–2300 BCE):

- Characterized by diverse stone tools and underground storage pits.

- Earliest evidence of betel nut ( Areca catechu ) use in South Asia with the discovery of two carbonized seeds.

- Dominance of chert microliths.

- Predominantly handmade pottery, some possibly made on a slow wheel, including coarse red and grey wares and burnished grey ware with red ochre post-firing painting.

- Presence of marine shell beads.

- Burials included urn and extended burials marked by stones, without grave goods.

Period IIB (c. 2300–2000 BCE):

- Continuity of storage pits and burial practices from Period IIA.

- Introduction of pots as grave goods.

- Increased variety and quantity of artefacts, including microliths, milling stones, beads of marine shell, stone, and terracotta, and a shell pendant.

- Discovery of animal and human terracotta figurines, including a female torso representation.

- Continuation of earlier pottery types with a slight increase in wheel-made pottery.

Periods III and IV (post-2000 BCE):

- Evidence of copper/bronze and iron.

Budihal

- Excavated by K. Paddayya and others, aiming to understand ash mounds in relation to ecology and material evidence.

- Located on a sandstone plateau with thin brown soil, comprising four localities (I–IV) within a 400 × 300 m area, each featuring an ash mound and habitational deposit.

- Western site area (about 4.5 ha) littered with chert tools and waste chert material, indicating a chert blade-working area.

- Nearby sandstone boulders with grinding and polishing grooves suggest stone tool production activities.

- Chert tools likely exported to other Neolithic settlements in the Shorapur doab and beyond.

Archaeological Findings at Budihal: A Detailed Overview

Excavation Findings

- The central area of the site at Budihal, known as Locality I, revealed that the ash deposits were situated in the middle of the site.

- Within the ash mound, two distinct areas were identified:

- Cattle-Penning Area : Located on the east side, this area showed evidence of multiple episodes of cattle penning, dung accumulation, and burning.

- Cow Dung Disposal Area : Found on the west side of the mound.

- A total of 12 structures were discovered in the 1.34-hectare habitational area surrounding the ash deposit, including:

- Platform for Chert Working : Used for processing chert, which was sourced from 5–6 km north of the site.

- Pottery Storage Area : Designated for storing pottery.

- Round Dwelling Units : These units had low walls made of stone blocks packed in mud.

Artefacts and Burials

- A total of 10 child burials were found in the habitational area, some in pits and others in pots.

- Artefacts recovered from the ash mound and residential area included:

- Red and grey pottery

- Ground stone tools

- Chert blades

- Bone tools, including axe heads

- Beads made of shell, bone, and semi-precious stones

Botanical and Faunal Remains

- Through the flotation of soil samples, seeds of three wild plants were identified: ber, Indian cherry, and amla (Emblic myrabolans). A few grains of domesticated horse gram were also found.

- Faunal remains from about 15 domesticated and wild animal species were identified, with the bones of domesticated cattle being the most numerous. This indicates that the Neolithic people of Budihal primarily specialized in cattle rearing, along with some sheep, goat, buffalo, and fowl.

- Bones of wild animals included nilgai, blackbuck, antelope, monitor lizard, tortoises, birds, fish, crabs, and molluscs.

- An intriguing discovery was the identification of a butchering area within the settlement, located on the southern side of the ash mound.

Chronology

- Eleven radiocarbon dates ranging from approximately 1900 to 1400 BCE were obtained for the ash mound and habitational area at Budihal. When calibrated, these dates provide a range of 2180 to 1600 BCE.

Community Feasting at Neolithic Budihal

Discovery of a Butchering Area

- In a trench excavated in the southern part of Budihal, the archaeological team found a floor made of a kankar-like material, which was actually a mixture of ash, clay, potsherds, bone, and charcoal. This mixture was rammed together to create a hard surface, covering an area of 200–250 square meters.

- The floor was strewn with a large number of animal bones, primarily from cattle but also from sheep, goats, buffalo, and wild animals, indicating that this was a butchering area. Stone tools, including chopping tools and chert blades, were also found, suggesting that meat was processed here.

Evidence of Meat Roasting

- Three small pits found in the northern part of the butchering area contained ashy soil, charcoal, and burnt bones, indicating that this was a site for roasting meat.

Community Use of the Area

- The size and location of the butchering floor, along with the large number of bones and tools, suggest that this area was used by the entire community or a large part of it, perhaps on special or ceremonial occasions when animals were killed and their meat shared.

- The presence of sandstone blocks, bone splinters, and bone artifacts indicates that bone tools were made on-site and used for marrow extraction and hide working.

Observations by Paddayya

- Paddayya noted that neolithic ash mounds and habitation sites were closely related, with ash mound sites being described as neolithic pastoral settlements with ash deposits.

- These sites are typically found in hilly areas near perennial water sources, with good pasture land but poor agricultural soils.

- Garbage from penning cattle and household refuse was dumped and periodically burnt to keep the settlement clean and protect against health hazards.

Ritual Significance

- The burning of cow dung could also have had ritual significance, aimed at promoting cattle fertility. Some ash mounds were so large that they may have served as regional or local centers for periodic cattle fairs.

- The evidence from Budihal is significant because it demonstrates the complementary relationship between ash mounds and what appears to be a long-term habitation site. However, it is not yet definitively proven that a similar situation existed at other locations. There may be variations among sites, with some being single, independent sites, while others consist of pairs or clusters, like Kupgal, Budihal, and Palavoy. Additionally, some sites may represent short-term camps of pastoralists, while others indicate more extended habitation.

There are differing opinions regarding the subsistence base of the southern Neolithic sites:

- Fully Sedentary Farmers: Some believe that Neolithic people were fully sedentary farmers who cleared forests for agriculture.

- Nomadic Pastoralists: Others argue that while agriculture was practiced to some extent, these people were primarily nomadic pastoralists.

- Sedentary Pastoralists: A third perspective is that they were sedentary pastoralists who did not engage in agriculture at all.

- Raymond and Bridget Allchin suggest that ash mound sites like Utnur and Kudatini represent seasonal cattle camps and indicate a transition from early cattle pastoralism to later agriculture. However, the early date from Watgal, which lacks ash mounds, shows that ash mound sites were not necessarily the earliest.

- The presence of faunal remains, ash mounds, terracotta figurines of humped cattle, and rock bruisings of cattle on rocks around some settlements highlights the importance of cattle rearing in the southern Neolithic. Cattle, specifically Bos indicus, dominate the faunal assemblage in both ash mound and non-ash mound sites. Sheep and goat bones are found in smaller quantities, while horse remains raise questions about whether they are wild or domesticated. Bones of water buffalo and pig, both wild and domesticated, occur occasionally, along with wild and domesticated fowl remains.

- Until recently, there was limited evidence of agriculture at South Indian Neolithic sites, with occasional discoveries of charred grain and grinding stones suggesting a focus on cattle rearing. Some scholars argued that the terrain, soil, and dry climate were unsuitable for agriculture. However, recent research has revealed a variety of plant remains at southern Neolithic sites, indicating the presence of millets as a staple crop, along with pulses and ber seeds. Fragments of wild areca nut were found at Watgal.

Harappan Trade and Craft Evidence

- Current evidence from various archaeological sites indicates limited craft or trade activities during the period in question.

- While copper and bronze objects have been found at several locations, there is no proof of local smelting or working of these metals. This raises the question of whether these objects were acquired through exchange or trade from other regions.

- For instance, a pair of gold earrings discovered at the Neolithic site of Tekkalakota suggests that the gold used in Harappan contexts may have originated from the Kolar fields in Karnataka. This finding implies a trade relationship between urban Harappan communities and Neolithic populations in South India.

- Additionally, marine shells and marine shell artifacts found at Watgal point to exchanges with coastal areas, likely along the western coast of India.

Chalcolithic Phase in Andhra Pradesh

- The onset of the Chalcolithic phase is evident at sites like Singanapalli and Ramapuram in the Kurnool district of Andhra Pradesh.

- These sites have been excavated, although comprehensive excavation reports are not yet available.

- Radiocarbon dating from Ramapuram suggests a timeframe of approximately 2455 to 2041 BCE for the site's occupation.

- Excavations at Ramapuram have revealed several significant findings, including:

- House floors plastered with lime, indicating advanced construction techniques.

- Wheel-made painted pottery, predominantly featuring black-on-red designs, showcasing artistic skill and technological development.

- Microliths, which are small stone tools typically used for hunting or gathering.

- Beads made from semi-precious stones, suggesting trade or access to a variety of materials.

The Life of Early Farmers

Early farming communities were often thought to be self-sufficient and in balance with their food supply and population. However, the situation is more complex than that. It's not just about having enough food; food plays a crucial role in human life beyond mere survival. The way food is obtained and consumed is a social activity and involves aspects like hospitality, gift-giving, trade, and social norms. Food preferences and preparation methods are important parts of social life, both within families and larger groups. For example, the site of Budihal shows how communities in the neolithic period prepared and shared food together.

- While we can make some guesses about the social and political structures of early farming communities, it's important to realize that these communities were not all the same. Some sites show evidence of small groups with simple social structures, while others indicate more complex societies. The way these communities made a living would have varied based on the resources available in their environment and how they adapted to it. Differences in tools, pottery, and housing suggest that there were various craft traditions and ways of life. Burial practices and objects used in rituals indicate different belief systems and customs among these early farmers.

- There is a perspective that life for farmers was easier compared to the struggle and lack of free time experienced by prehistoric hunter-gatherers. However, this view can be challenged, and it is an oversimplification to think of early farmers’ lives as comfortable and easy. Farmers were actually quite vulnerable. Just like today, they faced risks such as droughts leading to poor harvests, pests or diseases destroying crops, and storage issues like mould and rodents ruining their hard-earned grain reserves.

- Despite the differences in the lifestyles of early farmers and the need to move beyond stereotypical ideas, it is possible to identify certain general features of the impact of the transition from hunting-gathering to food production. Earlier, it was pointed out that elements of sedentary living can be seen among certain hunting-gathering groups, while some farmers and pastoralists retain a migratory lifestyle. There are also different views on whether sedentary living preceded or followed the beginnings of agriculture.

- However, there is no doubt that in the long run, the transition to agriculture did lead to increasing levels of sedentariness among most communities. Studies of nutrition and disease based on an analysis of human bones suggest that hunter-gatherers had a high-protein diet, one that was more varied, balanced, and healthy compared to that of early farmers, whose diet tended to be high in carbohydrates, with an emphasis on cereals or root crops. Sedentary people were also more vulnerable to infectious diseases and epidemics than nomadic groups. This may help explain the high incidence of disease reflected in the bones of certain early farming communities.

- Living for long periods in one place would have fostered a stronger connection between people and their environmental niche. A sedentary lifestyle, along with the associated agricultural diet, would have reduced stress on women during pregnancy and provided more stable conditions for mothers and children after childbirth. Additionally, high-carbohydrate diets are linked to shorter birth intervals.

- All these factors would have contributed to higher birth rates. Sedentary living would have been easier for children and the elderly, potentially leading to lower death rates and increased life expectancy. For these reasons, the advent of food production would, in the long run, have resulted in population growth and changes in the age profiles within communities. Food production necessitated new toolkits and equipment.

- It also involved a different scheduling of subsistence activities and shifts in the contributions of men, women, children, and the elderly. Moreover, there would have been a change in the food ethic—hunter-gatherers typically collect food for immediate consumption on a short-term basis. In contrast, farmers needed to produce and store food for future use. The focus shifted from meeting immediate daily needs to long-term planning and strategies for food production and storage.

- Some researchers suggest that women might have played a leading role in the early experiments of plant domestication. This idea comes from studies showing a strong link between women and horticultural activities. In hunting-gathering societies, where men typically hunted and women gathered food, it seems plausible that women were the pioneers of early agriculture.

- Additionally, since pottery is associated with food storage and cooking—tasks often linked to women—it is possible that they were instrumental in the technological advancements of pottery making. Modern potters have noted that creating pots is a time-consuming process involving more than just the potter shaping the final product. Women and children might have contributed by collecting and processing clay, gathering firewood, stacking it in the kiln, and decorating the pots. While ethnographic evidence is not definitive, it is compelling in this context, suggesting women’s involvement in significant cultural progress during the shift to food production.

Craft Specialization and Trade in the Neolithic

- The neolithic period, often associated with basic subsistence activities, also witnessed specialized crafts and long-distance trade in locations like Mehrgarh. Sites such as Kunjhun and Ganeshwar show advanced craft traditions and specialization. Evidence from various sites indicates the presence of distinct areas within settlements designated for specific activities like cattle rearing, craft production, and butchering. This division reflects the community's collective decision-making in organizing space and tasks.

- Some neolithic communities were engaged with early urban cultures, indicating a level of interaction beyond simple subsistence.

Social Organization and Political Control

- As larger groups began to settle in villages, they needed to develop new ways of interacting and cooperating, different from those of hunter-gatherer bands. Early farming and pastoral communities were likely differentiated by age and sex.

- Differences in house sizes and grave goods at some sites suggest the presence of social hierarchies. To regulate economic activities and social relations, these larger groups would have required some form of political organization and control.

Changes in Cultic and Belief Systems

The shift in subsistence practices likely brought about changes in symbolic and belief systems. However, defining religious or cultic activities and identifying their traces in the archaeological record poses a challenge. In the previous chapter, we noted that some of the palaeolithic and mesolithic art remains may have been linked to magico-religious beliefs and hunting rituals.

- The advent of crop cultivation and animal domestication probably heightened concerns about fertility and magico-religious methods of controlling it. From neolithic levels onwards, terracotta female figurines found at certain sites, particularly in the north-western zone, have often been labeled as 'Mother Goddesses.' Farming communities likely associated women with fertility due to their ability to give birth, and it is possible that they worshipped images of goddesses linked to fertility.

- However, the interpretation of these female figurines is highly subjective. It is unclear whether they represented goddesses, toys, decorative items, or clay portraits of ordinary women. Similarly, the humped bull figurines discovered at sites such as Rana Ghundai, Mehrgarh, Mundigak, Bala Kot, Gilund, Balathal, and Chirand raise questions about their cultic significance. Unless their form or context clearly indicates religious or cultic meaning, caution is necessary when making inferences about the role and function of terracotta figurines.

Female Figurines: Ordinary Women or Goddesses?

- In the past, researchers commonly labeled all female figurines found at archaeological sites as ‘Mother Goddesses.’ This was based on the belief that fertility goddess worship was crucial in agricultural societies worldwide. Additionally, this perspective was influenced by later Hindu practices where goddess worship was significant. However, scholars now recognize the stylistic and technical variations among different groups of female figurines.

- Moreover, it is clear that not all goddesses were part of a single cult, and not all ancient goddesses were linked to motherhood. Given these considerations, the term ‘Mother Goddess’ is being replaced with the more neutral phrase ‘female figurines with likely cultic significance.’ This change acknowledges that while some figurines may have had religious or cultic meanings, such as being objects of worship or votive offerings in domestic rituals, not all of them served such purposes. The significance or function of these figurines, whether human or animal, needs to be evaluated based on their context and not assumed. The context in which they were found is crucial for understanding their possible meanings.

Female Figurine from Mehrgarh

- The practice of intentional and standardized burials did not originate in the neolithic or neolithic–chalcolithic phase, but their occurrence increased during this period. These burials indicate the importance attached to the bodily remains of the deceased. When burials are found within habitation areas, it is challenging to determine whether the dead were honored, feared, or a combination of both.

- The patterns in burial orientation and form suggest the presence of funerary customs followed by certain community members. Multiple burials may signify either simultaneous deaths or strong kinship bonds. The tradition of covering bodies with red ochre before burial at Mehrgarh implies a fertility ritual. The joint burials of humans and animals at Burzahom reflect a close bond between people and the animals involved.

- The distinction between simple and elaborate graves likely represents variations in funerary customs associated with individuals of different social ranks. The inclusion of food items among grave goods indicates a belief in an afterlife. Secondary burials suggest multi-stage funerary practices and rituals. Further investigation is needed to understand the social implications of changes in burial practices at specific sites.

Conclusions

- There is a significant variation in the timeline and specifics of how early food-producing societies adapted to their environments. Around 7000–3000 BCE, food-producing villages began to appear in Baluchistan and the northern fringes of the Vindhyas.

- The number and geographical spread of these settlements increased around 3000–2000 BCE. The early stages of animal and plant domestication did not result in the extinction of hunting and gathering. One notable aspect of this period was the coexistence and interaction among various communities, including neolithic, neolithic–chalcolithic, rural chalcolithic, urban chalcolithic, and hunter-gatherer groups.

- In the long run, the significance of the advent of food production lay not only in its immediate effects but also in the potential it created for future changes. In certain regions, the process of food production and its associated cultural developments eventually paved the way for the emergence of proto-urban settlements and, subsequently, fully developed cities.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on The Transition to Food Production: Neolithic– Chalcolithic, and Chalcolithic Villages - 3 - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What are the significant archaeological findings at Burzahom related to bone tools? |  |

| 2. What is the significance of the Gufkral site in the context of Neolithic culture in Kashmir? |  |

| 3. How did the Chalcolithic cultures in Rajasthan contribute to the understanding of early human societies? |  |

| 4. What are the characteristics of the Ahar culture sites in Rajasthan? |  |

| 5. What changes occurred in cultic and belief systems during the transition from Neolithic to Chalcolithic periods? |  |