UPSC Mains Answer PYQ 2021: History Paper 1 (Section- A) | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Section ‘A’

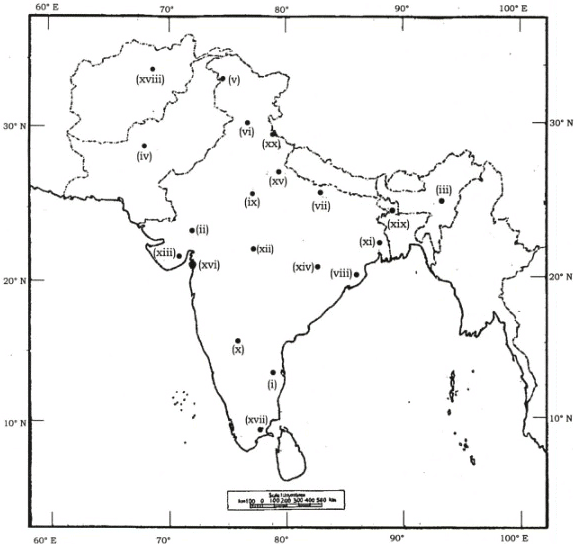

Q.1. Identify the following places marked on the map supplied to you and write a short note of about 30 words on each of them in your Question-cum-Answer Booklet. Locational hints for each of the places marked on the map are given below serial wise: (20 x 2.5 = 50)

(i) Paleolithic site

(ii) Mesolithic site

(iii) Neolithic site

(iv) Neolithic-Chalcolithic site

(v) Harappan site

(vi) Proto-historic and historic site

(vii) Inscriptional site

(viii) Jain monastic site

(ix) Coin hoard

(x) Paleolithic site

(xi) Terracotta site

(xii) Rock-cut caves

(xiii) Ancient learning centre

(xiv) Political and cultural centre

(xv) Buddhist site

(xvi) Ancient port

(xvii) Early historic site

(xviii) Ivory hoard

(xix) Buddhist monastic centre

(xx) Temple complex

(i) Paleolithic site: Bhimbetka - A UNESCO World Heritage Site in Madhya Pradesh, known for its ancient rock shelters and paintings dating back to the Paleolithic Age.

(ii) Mesolithic site: Bagor - Located in Rajasthan, Bagor is an important Mesolithic site known for its distinctive stone tools, bone artifacts, and evidence of early human settlements.

(iii) Neolithic site: Burzahom - A significant Neolithic site in Jammu and Kashmir, known for its unique underground dwelling pits and ancient pottery.

(iv) Neolithic-Chalcolithic site: Mehrgarh - Located in Balochistan, Pakistan, Mehrgarh is a crucial site showcasing the transition from Neolithic to Chalcolithic Age, with evidence of early farming and metallurgy.

(v) Harappan site: Dholavira - A prominent site of the Indus Valley Civilization in Gujarat, known for its well-planned urban settlement and water management system.

(vi) Proto-historic and historic site: Arikamedu - An ancient settlement in Tamil Nadu, known for its trade relations with the Roman Empire and archaeological evidence of glass bead making.

(vii) Inscriptional site: Junagadh - Located in Gujarat, Junagadh is famous for its Ashokan edicts inscriptions and the Girnar rock inscriptions of Rudradaman and Skandagupta.

(viii) Jain monastic site: Udayagiri - An ancient Jain monastic site in Odisha, known for its rock-cut caves, inscriptions, and sculptures.

(ix) Coin hoard: Sonkh - Located in Uttar Pradesh, Sonkh is known for the discovery of a large hoard of ancient coins, including Indo-Greek, Kushan, and Gupta coins.

(x) Paleolithic site: Attirampakkam - An important Paleolithic site in Tamil Nadu, known for its unique Acheulian stone tools and evidence of early human habitation.

(xi) Terracotta site: Kaushambi - Located in Uttar Pradesh, Kaushambi is known for its ancient terracotta sculptures, pottery, and remains of a fortified city.

(xii) Rock-cut caves: Ajanta - A UNESCO World Heritage Site in Maharashtra, famous for its exquisite rock-cut Buddhist caves and paintings dating back to the 2nd century BCE.

(xiii) Ancient learning centre: Nalanda - An ancient learning centre in Bihar, known for its renowned university that attracted scholars from across Asia during the Gupta and Pala empires.

(xiv) Political and cultural centre: Pataliputra - The ancient capital city of the Mauryan, Shunga, and Gupta empires, located in present-day Patna, Bihar.

(xv) Buddhist site: Sarnath - An important Buddhist pilgrimage site in Uttar Pradesh, where Gautam Buddha delivered his first sermon after attaining enlightenment.

(xvi) Ancient port: Lothal - A significant Harappan site in Gujarat, known for its well-planned dockyard and maritime trade activities.

(xvii) Early historic site: Amaravati - Located in present-day Andhra Pradesh, Amaravati was an early historic city, known for its Buddhist stupas and sculptures.

(xviii) Ivory hoard: Begram - An ancient site in Afghanistan, famous for the discovery of a large hoard of ivory artifacts, believed to be of Indian origin.

(xix) Buddhist monastic centre: Vikramashila - An ancient Buddhist monastic centre in Bihar, known for its university that flourished during the Pala dynasty.

(xx) Temple complex: Khajuraho - A UNESCO World Heritage Site in Madhya Pradesh, famous for its intricately carved Hindu and Jain temples built during the Chandela dynasty.

Q.2. Answer the following:

(a) Do you agree that ecological factors influenced the flow and ebb of the Harappan Civilization? Comment. (20 Marks)

Yes, I agree that ecological factors significantly influenced the flow and ebb of the Harappan Civilization. The Harappan Civilization, also known as the Indus Valley Civilization, flourished in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent from around 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. It was one of the world's earliest urban civilizations, characterized by well-planned cities, impressive architecture, and advanced technologies. However, the civilization eventually went into decline and ultimately disappeared.

Several factors have been proposed to explain the decline of the Harappan Civilization, including invasions, social unrest, and economic decline. However, ecological factors seem to have played a significant role in the civilization's rise and fall. Some of the key ecological factors that influenced the Harappan Civilization include:

1. Climate change: The Harappan Civilization thrived during a period of relatively stable and wet climate conditions, which facilitated agriculture and allowed the civilization to grow. However, around 1900 BCE, the climate in the region began to change, becoming drier and more variable. This led to a reduction in agricultural productivity, which would have affected the food supply and the economic stability of the civilization.

2. River dynamics: The Harappan Civilization was centered around the Indus River and its tributaries, which provided water for irrigation and transportation. Changes in the river's course, such as the drying up of the Saraswati River and the shifting of the Ghaggar-Hakra River system, could have had a significant impact on the sustainability of the civilization. These changes may have been caused by tectonic activity, climate change, or a combination of both.

3. Deforestation and soil degradation: The rapid growth of the Harappan Civilization led to an increased demand for resources, such as timber and fertile land. This likely resulted in deforestation and soil degradation, which would have adversely affected agricultural productivity and the overall sustainability of the civilization.

4. Natural disasters: The Harappan Civilization was prone to natural disasters, such as floods and droughts, which would have disrupted agriculture and trade. For example, the city of Mohenjo-Daro was severely affected by floods, which led to the abandonment of the city and its eventual decline.

To conclude, ecological factors played an important role in the rise and fall of the Harappan Civilization. Climate change, river dynamics, deforestation, soil degradation, and natural disasters all contributed to the decline of this once-thriving civilization. These factors, in combination with other social, political, and economic factors, led to the ultimate collapse of the Harappan Civilization.

(b) Do you consider that the Upanishadic principles embody the high point of Vedic religious thought? Comment. (15 Marks)

Yes, I believe that the Upanishadic principles embody the high point of Vedic religious thought. The Upanishads are considered the philosophical essence of the Vedas, and they significantly contributed to the development of Indian religious, spiritual, and philosophical thought. The principles laid down in the Upanishads reflect a more mature and sophisticated understanding of the universe, the self, and divine reality.

There are several reasons why the Upanishadic principles can be considered the pinnacle of Vedic religious thought:

1. Shift from ritualism to spiritualism: The early Vedic texts, such as the Rigveda, Samaveda, and Yajurveda, focused primarily on rituals and sacrifices to appease various gods and goddesses. However, the Upanishads shifted the focus from ritualism to spiritualism, emphasizing the importance of personal spiritual development and self-realization. This transition marked a significant change in the way people approached their religious life and understanding of the divine.

2. Concept of Brahman: The Upanishads introduced the concept of Brahman, the ultimate reality or the absolute, which is beyond all names, forms, and attributes. This idea represented a significant departure from the polytheistic beliefs of the earlier Vedic period, where numerous gods and goddesses were worshipped. The Upanishadic concept of Brahman provided a unifying principle for understanding the nature of the divine and paved the way for the development of monotheistic and monistic philosophies in later Indian thought.

3. Doctrine of Atman: The Upanishads also introduced the concept of Atman, the individual self or soul, which is considered to be the essence of all living beings. They emphasized the idea that the ultimate goal of human life is to realize the unity of the individual soul (Atman) with the supreme reality (Brahman). This spiritual quest for self-realization and ultimate liberation (Moksha) became a central theme in the religious and philosophical traditions of India.

4. Philosophical inquiries: The Upanishads are known for their profound philosophical inquiries into the nature of reality, consciousness, and the human condition. They contain dialogues between sages and their students, exploring various metaphysical and existential questions. Through these dialogues, the Upanishads provided a platform for the development of diverse philosophical schools, such as Advaita Vedanta, which became significant in shaping Indian intellectual and spiritual traditions.

5. Ethical teachings: The Upanishadic principles also emphasized the importance of ethical living and moral conduct. They advocated values such as truthfulness, non-violence, compassion, self-discipline, and detachment from material possessions. These ethical teachings laid the foundation for the development of several moral and ethical codes in later Indian thought, such as the concept of Dharma in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

In conclusion, the Upanishadic principles mark a significant shift in Vedic religious thought, moving away from ritualism and towards a deeper understanding of the self, the universe, and the divine reality. By introducing the concepts of Brahman and Atman, and promoting philosophical inquiry and ethical living, the Upanishads laid the foundation for the development of India's rich spiritual, religious, and philosophical traditions. Therefore, they can be considered the high point of Vedic religious thought.

(c) Analyze the significance of external influences and indigenous development on post-Mauryan art. (15 Marks)

Post-Mauryan art refers to the art and architecture that emerged after the decline of the Mauryan Empire in India around 200 BCE. This period witnessed significant developments in Indian art, influenced by external factors such as foreign invasions and trade, as well as indigenous developments within the subcontinent. The most prominent features of post-Mauryan art are the Gandhara and Mathura schools of art, which were products of the fusion of external influences and indigenous elements.

External Influences:

1. Foreign invasions: The post-Mauryan period saw a series of invasions by foreign powers, such as the Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythians, Parthians, and Kushanas. These invasions led to cultural exchanges, especially in the field of art. The most notable example of this is the Gandhara school of art, which was influenced by the Hellenistic art of the Greeks. The Gandhara art is characterized by a fusion of Indian and Greek elements, such as the depiction of the Buddha in the Greco-Roman style, with curly hair, a well-defined nose, and expressive eyes.

2. Trade relations: The post-Mauryan period saw extensive trade relations between India and the Mediterranean world, Central Asia, and China. These trade connections facilitated the exchange of ideas, artistic techniques, and styles. The influence of Roman art can be seen in the use of sculptural reliefs in the decoration of Buddhist stupas, such as those at Sanchi and Amaravati.

Indigenous Developments:

1. Mathura school of art: In contrast to the Gandhara school, the Mathura school of art was primarily an indigenous development, although it did incorporate some external elements. This school of art is characterized by the use of red sandstone and a more Indian style of depicting the Buddha, with a round face, smooth limbs, and a more serene expression. The Mathura school also introduced the concept of the anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha, which became a significant feature of Buddhist art in India and other regions.

2. Narrative art: The post-Mauryan period saw the development of narrative art, which depicted stories from the life of the Buddha, Jataka tales, and other religious and secular themes. This was a significant development, as it allowed for the communication of religious and moral teachings through visual means. The narrative panels on the railings and gateways of the Sanchi stupa, which depict scenes from the life of the Buddha and Jataka tales, are excellent examples of this technique.

3. Architectural developments: The post-Mauryan period also witnessed significant developments in architecture, such as the construction of free-standing temples, rock-cut cave temples, and the evolution of the stupa. The stupa, which originated during the Mauryan period, evolved into more elaborate structures, with decorative gateways, railings, and sculptural reliefs. The rock-cut cave temples, such as those at Ajanta and Ellora, are examples of the fusion of architecture, sculpture, and painting, creating a unique artistic expression.

In conclusion, the post-Mauryan art was a period of significant growth and innovation, influenced by both external factors and indigenous developments. The fusion of foreign artistic styles with indigenous techniques resulted in unique artistic expressions, such as the Gandhara and Mathura schools, which had a lasting impact on Indian art and architecture. The post-Mauryan art also marked the beginning of a more narrative and communicative form of art, reflecting the religious and cultural diversity of the Indian subcontinent.

Q.3. Answer the following:

(a) Will it be proper to consider the megaliths to represent a single, homogeneous or contemporaneous culture? What kind of material life and cultural system is revealed in megalithic cultures? (20 Marks)

It would not be proper to consider megaliths as representing a single, homogeneous, or contemporaneous culture. Megaliths are large stone structures, typically used as burial monuments, found across various regions and time periods in different parts of the world, such as Europe, Africa, and Asia. These structures are not exclusive to a specific culture or time period, and their construction and use can vary greatly depending on the region and society they belong to.

Material life and cultural systems in megalithic cultures varied depending on the region and time period. However, some common features of megalithic cultures include:

1. Social Stratification: The construction of megaliths often required significant labor, resources, and organization, suggesting the presence of a hierarchical society, with some individuals possessing considerable power and wealth.

2. Rituals and Beliefs: Megaliths were commonly used as burial monuments, indicating that the people who built them had a strong belief in an afterlife or ancestor worship. They might have also been used as sites for religious or ritualistic activities.

3. Trade and Exchange: The presence of exotic objects in some megalithic burials, such as precious metals, ornaments, and pottery, suggests that these societies had developed trade networks and participated in long-distance exchange.

4. Art and Craftsmanship: Some megaliths display intricate carvings and designs, indicating that these societies had skilled artisans who could work with stone and other materials.

Examples:

1. South India: The megalithic culture in South India, particularly in present-day Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, is characterized by the construction of various types of megalithic structures, such as Dolmens, Menhirs, and Cairn circles. These structures were typically used as burial sites, and the material culture found within them includes pottery, iron tools, and ornaments, which suggest a level of technological advancement and trade.

2. Northeast India: Megalithic cultures in Northeast India, such as in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, are known for constructing Menhirs and table-stone structures. These structures were used for various purposes, including commemorating the dead, marking important events, and as territorial markers. The material culture associated with these megaliths includes stone and iron tools, pottery, and ornaments made of gold, silver, and other materials.

In conclusion, it is not appropriate to consider megaliths as representing a single, homogeneous, or contemporaneous culture. Instead, megalithic structures should be viewed as a reflection of the diversity of societies and cultural systems that existed across various regions and time periods.

(b) How would you characterize the nature of Mauryan state on the basis of Kautilya's Arthashastra? (15 Marks)

The Mauryan state, as characterized by Kautilya's Arthashastra, can be described as a highly centralized, bureaucratic, and well-organized administration, with the king at the apex of the hierarchy. The Arthashastra is a treatise on statecraft, economic policy, and military strategy, attributed to Kautilya, also known as Chanakya, who was a chief advisor to Emperor Chandragupta Maurya.

1. Centralized Administration: The Arthashastra emphasizes the central role of the king in the administration of the state. The king was responsible for the welfare of the subjects and the protection of the realm. Kautilya advised the king to have a council of ministers for assistance and guidance in decision-making.

2. Bureaucracy and Division of Power: The Mauryan state had a hierarchical bureaucracy, with various officers and officials responsible for different aspects of administration. The Arthashastra mentions several categories of officials, such as the Adhyakshas (Superintendents), who were in charge of specific departments like agriculture, trade, and mining. There were also the Rajukas (revenue officers) responsible for tax collection and administration of justice at the local level.

3. Espionage and Intelligence: The Arthashastra places a great emphasis on the importance of an efficient intelligence and espionage system. The spies were responsible for collecting information about internal and external threats to the state, as well as reporting on the activities of officials and subjects. This shows that the Mauryan state was vigilant and proactive in maintaining law and order.

4. Economy and Taxation: The Mauryan state had a well-defined economic policy, with a focus on agriculture and trade. The Arthashastra suggests various measures to improve agricultural productivity, such as the construction of irrigation facilities and the promotion of scientific methods of cultivation. The state also regulated trade and commerce, levying taxes and duties on various goods and services. The land revenue was the main source of income for the state, and the Arthashastra prescribes various rates of taxation for different types of land and crops.

5. Law and Order: The Arthashastra emphasizes the importance of maintaining law and order in the state. It provides detailed guidelines for the punishment of different crimes and prescribes various methods of interrogation and trial. The state was responsible for providing justice to its subjects and ensuring the protection of their rights and liberties.

6. Diplomacy and Foreign Relations: The Mauryan state had a well-defined foreign policy, based on the principles of realpolitik, as articulated in the Arthashastra. Kautilya advocated the use of diplomacy, alliances, and military power to achieve the state's objectives in its relations with other countries. The concept of the "Mandala" or the circle of states, which suggests that a state's immediate neighbors are its natural enemies and the neighbors of those neighbors are its natural allies, reflects the pragmatic approach to foreign relations in the Mauryan state.

In conclusion, the nature of the Mauryan state, as characterized by Kautilya's Arthashastra, was a highly centralized and well-organized administration, with the king playing a pivotal role in governance. The state had an efficient bureaucracy, a strong economy, and a focus on maintaining law and order, which contributed to its success as one of the largest and most powerful empires in ancient India.

(c) How did the Varnashrama Dharma manifest the increasing social complexities in the Gupta and post-Gupta period arising from social and economic developments? (15 Marks)

The Varnashrama Dharma, a system of social organization based on the four-fold division of society into castes (varnas) and stages of life (ashramas), played a significant role in the manifestation of increasing social complexities in the Gupta and post-Gupta period. The social and economic developments during these periods led to the emergence of new social groups and economic classes, which further complicated the Varnashrama Dharma system. The following points illustrate this complexity:

1. Emergence of new castes and sub-castes: The Gupta and post-Gupta period witnessed the emergence of numerous new castes and sub-castes due to intermixing of different social groups and the rise of new professions. For instance, the Kayasthas (scribes), who held significant positions in the administration, emerged as a powerful caste during this period. Similarly, the Vaisyas branched off into various sub-castes, like the Baniks (merchants), who played a crucial role in trade and commerce.

2. Occupational diversification: The expansion of agriculture, trade, and commerce during the Gupta period led to the emergence of new occupations and professions. Consequently, the Varnashrama Dharma system could not confine people to their traditional hereditary professions. For example, the Shudras, who were traditionally laborers and service providers, entered into various crafts and professions, thereby breaking the rigid occupational hierarchy.

3. Rise of the feudal system: The Gupta and post-Gupta period saw the rise of a feudal system, which led to the decentralization of power and the emergence of powerful landowning classes. These landowners, known as the Samantas, often claimed Kshatriya status and gradually became a distinct social group. This further complicated the Varnashrama Dharma system and blurred the lines between the different varnas.

4. Fluidity in the caste system: The caste system during the Gupta and post-Gupta period became more fluid, as people were allowed to change their varnas under certain circumstances. For instance, the Brahmanical texts, such as the Smritis, provided provisions for the inclusion of foreigners like the Huns, who had invaded India during the post-Gupta period, into the caste system. Similarly, the concept of "Anuloma" marriages (marriages between a man of a higher caste and a woman of a lower caste) also contributed to the fluidity of the caste system.

5. Influence of Buddhism and Jainism: The influence of heterodox sects like Buddhism and Jainism, which rejected the caste system and promoted social equality, further challenged the Varnashrama Dharma. The monastic orders of these religions provided an alternative way of life for people who wanted to escape the rigid caste system. This led to a decline in the dominance of the Brahmins and further complicated the social hierarchy.

In conclusion, the Varnashrama Dharma, which was initially a simpler system of social organization, manifested the increasing social complexities in the Gupta and post-Gupta period due to various social and economic developments. The emergence of new social groups, the rise of the feudal system, occupational diversification, fluidity in the caste system, and the influence of heterodox sects contributed to the evolution and transformation of the Varnashrama Dharma during these periods.

Q.4. Answer the following:

(a) "The political and economic needs of rulers, combined with economic and status needs of the merchant class, together provided the receptive cultural milieu in which Buddhism flourished." Comment. (20 Marks)

The statement highlights that the growth and success of Buddhism as a religion in ancient India can be attributed to the support and patronage it received from rulers and the merchant class. The rulers and merchants had their own political and economic needs and found Buddhism to be a suitable religion to fulfill those needs. Let us analyze how the political and economic needs of rulers and the merchant class contributed to the flourishing of Buddhism in ancient India.

1. Political needs of rulers: Many rulers in ancient India embraced Buddhism as a means to extend their political influence and control over their subjects. For example, Emperor Ashoka embraced Buddhism after the Kalinga War and actively promoted it throughout his empire. Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to various parts of the Indian subcontinent and beyond, establishing Buddhism as a major religion in the region. This patronage by Ashoka and other rulers helped Buddhism gain prominence and acceptance among the masses.

2. Economic needs of rulers: Buddhism provided rulers with an opportunity to gain economic advantages. For example, Buddhist monasteries and establishments in ancient India attracted traders, artisans, and craftsmen, leading to the growth of trade and commerce in the region. The rulers, in turn, benefitted from the increased economic activity and generated revenue through taxes and trade. The support for Buddhism thus became an investment for these rulers in promoting their economic interests.

3. Economic needs of the merchant class: The merchant class of ancient India also found Buddhism to be a religion that catered to their economic needs. Buddhism's emphasis on non-violence, tolerance, and compassion resonated with the merchant class, who relied on peaceful trade relations for their livelihood. The support for Buddhism further strengthened their trade relations with Buddhist regions and communities.

4. Status needs of the merchant class: The merchant class in ancient India was often looked down upon by the higher castes in the traditional Hindu social hierarchy. The support for Buddhism allowed them to assert their social status and identity. Buddhism did not discriminate against people based on their caste or social status, and this egalitarianism appealed to the merchant class.

In conclusion, the political and economic needs of rulers, combined with the economic and status needs of the merchant class, together provided the receptive cultural milieu in which Buddhism flourished. The patronage and support from these influential sections of society enabled Buddhism to grow and spread, both within and beyond the Indian subcontinent.

(b) Large number of land grants in hitherto non-arable tracts invariably meant expansion of agriculture in early medieval India. How did the management of hydraulic resources (different types of irrigation works) facilitate expansion of agriculture in this period? (15 Marks)

The management of hydraulic resources played a crucial role in facilitating the expansion of agriculture in early medieval India. The increasing number of land grants in previously non-arable tracts demanded efficient utilization of water resources to make the lands cultivable. This led to the construction and maintenance of various types of irrigation works, which in turn made it possible to expand agriculture in the region.

1. Construction and maintenance of tanks: Tanks were the most popular method of irrigation in early medieval India. They were built by constructing embankments across low-lying areas or by excavating the ground to store water. These tanks were primarily rain-fed, and their water was used for both irrigating fields and for domestic purposes. The construction and maintenance of these tanks were often the responsibility of the village community, with the support of the local rulers. The tanks played a crucial role in providing much-needed water for agriculture, thereby helping in the expansion of cultivation.

2. Wells and step-wells: Wells and step-wells were other important sources of irrigation in early medieval India. These were dug deep into the ground to tap the groundwater, which was then used for irrigation and domestic purposes. The development of wells and step-wells helped in bringing more land under agriculture, especially where the construction of tanks was not feasible.

3. Canals: Canals were constructed to channel water from rivers to areas where irrigation was needed. In some cases, canals were built to divert water from one river to another, to bring water to areas which were not directly accessible by the rivers. The construction of canals played an important role in expanding agriculture in the region, as it enabled farmers to bring water to their fields, even in areas that were far away from natural water sources.

4. River embankments and bunds: River embankments and bunds were built to regulate the flow of water in the rivers and prevent flooding. These embankments helped in making the adjoining lands cultivable, by controlling the floodwaters and preventing soil erosion. This, in turn, facilitated the expansion of agriculture in the region.

5. Technological advancements: In addition to the above methods, early medieval India also witnessed technological advancements in the field of irrigation. For instance, the use of Persian wheels (or Araghatta) helped in lifting water from wells and canals to irrigate fields at higher elevations.

In conclusion, the management of hydraulic resources in early medieval India played a significant role in the expansion of agriculture in the region. The construction and maintenance of tanks, wells, step-wells, canals, and river embankments, along with technological advancements, helped in making previously non-arable tracts cultivable. This, in turn, contributed to the overall growth of agricultural production and the economy during this period.

(c) Discuss the relationship between emergence of literature in vernacular languages and formation of regional identities in early medieval India. (15 Marks)

The emergence of literature in vernacular languages and the formation of regional identities in early medieval India are deeply intertwined. The period between the 6th and 13th centuries CE is considered as the early medieval period in Indian history, during which there was a significant shift from the use of classical Sanskrit to vernacular languages in literature. This development played a crucial role in shaping regional identities and fostering the growth of regional cultures in various parts of the Indian subcontinent.

1. Emergence of Vernacular Languages: During the early medieval period, several vernacular languages emerged as literary and cultural mediums, such as Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Bengali, Marathi, Gujarati, and others. Local rulers and elites supported and patronized these languages, which led to the growth of a rich literary tradition in these regions. The emergence of regional languages also helped in the creation and strengthening of regional identities.

2. Regional Literatures: The emergence of regional languages led to the development of regional literature, which played a critical role in shaping regional identities. For example, in Tamil Nadu, the Sangam literature (c. 3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE) is a collection of Tamil poems and songs that reflect the life, culture, and beliefs of the people living in the region. Similarly, the Vachana literature in Kannada (c. 11th-12th centuries CE) reflects the socio-religious developments in the region during the time. The regional literatures thus helped in creating a sense of belonging and pride among the people towards their language, culture, and history.

3. Formation of Regional Identities: The development of vernacular languages and the growth of regional literature contributed to the formation of regional identities. People began to associate themselves with their regional language, culture, and history, and this led to a sense of collective identity among the people living in a particular region. For instance, the Tamil identity in southern India, the Bengali identity in eastern India, and the Marathi identity in western India can be traced back to the early medieval period and the growth of vernacular literature.

4. Impact on Religion and Philosophy: The emergence of vernacular languages also had a profound impact on religion and philosophy in early medieval India. During this period, religious and philosophical ideas were disseminated in regional languages, which made them more accessible to the common people. This led to the growth of regional religious movements like the Bhakti movement in south India, the Nath tradition in north India, and the Sufi movement in various parts of the Indian subcontinent. These movements played a crucial role in shaping regional identities and fostering harmony among different religious and social groups.

In conclusion, the emergence of literature in vernacular languages and the formation of regional identities in early medieval India were interrelated processes that shaped the socio-cultural landscape of the Indian subcontinent. The development of regional languages and literature provided a platform for the expression of local identities, which in turn contributed to the creation of distinct regional cultures and traditions. This phenomenon has left an indelible mark on the history and culture of India, and its legacy can still be seen in the vibrant regional identities that exist in the country today.

|

367 videos|995 docs

|