What Happens to Nitrogen in Soils? - 1 | Agriculture Optional Notes for UPSC PDF Download

Introduction

Efficient crop production necessitates a sufficient supply of all vital plant nutrients. However, in modern agriculture, the use of commercial nitrogen (N) fertilizers is essential to increase production, maintain profitability, and provide affordable food and fiber. Among all plant nutrients, nitrogen is generally required in the largest quantity by crops.

The environmental impact of nitrogen fertilizers has been a long-standing concern. Worries about nitrogen pollution in rivers, lakes, and groundwater have made agricultural producers increasingly conscious of their potential role in overall pollution.

To use nitrogen effectively and minimize its negative environmental effects, producers must acquire knowledge about the chemistry of nitrogen and how it enters and exits the soil.

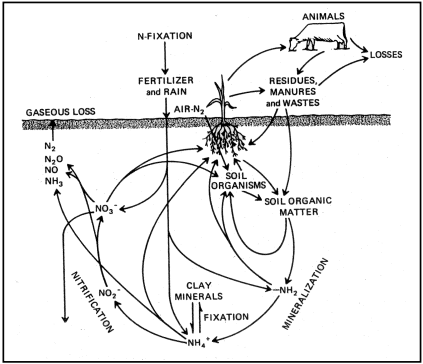

Agricultural producers rely significantly on commercial fertilizers to introduce nitrogen into the soil. Nitrogen undergoes a continuous cycle through plant and animal waste residues and organic matter in the soil. Crops, gaseous emissions, runoff, erosion, and leaching are ways through which nitrogen is depleted from the soil. The extent and methods of nitrogen loss depend on the specific soil's chemical and physical characteristics. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the potential gains and losses of soil nitrogen.

Chemistry of Nitrogen

Approximately 79 percent of the air we inhale is composed of nitrogen. In a fertile prairie soil's top 6 inches, there can be 2 to 3 tons of nitrogen per acre. The air above the same acre contains roughly 35,000 tons of inert nitrogen gas (N2). The majority of the nitrogen found in soil originally came from N2 gas, and virtually all the nitrogen in the atmosphere exists as N2 gas. This inert nitrogen is not usable by plants until it undergoes a transformation into ammonium (NH4+) or nitrate (NO3-) forms.

There are three primary methods for converting nitrogen gas (N2) into ammonium (NH4+):

- Free-Living N2-Fixing Bacteria

- N2-Fixing Bacteria in the Roots of Leguminous Plants

- Nitrogen Fertilizer Production Factories

Another notable method for converting N2 is through lightning. When lightning strikes, it superheats the air and transforms nitrogen gas into nitrate (NO3-) and nitrite (NO2-). Lightning events could contribute anywhere from 1 to 50 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year that is accessible to plants.

While nitrogen can enter the soil in various chemical forms, it ultimately transforms into the inorganic nitrate (NO3-) ion. As shown in Figure 1, plants can utilize NO3-, it can change back to nitrogen gas, or it can leach downward with soil water.

Common sources of nitrogen added to soils include commercial fertilizers, plant residues, animal manures, and sewage. Application rates can vary significantly, with single applications reaching levels as high as 150 pounds.

Figure 1: The nitrogen cycle is a complex system involving the air, soil and plant.

Figure 1: The nitrogen cycle is a complex system involving the air, soil and plant.

For crops like coastal bermudagrass, it may be necessary to apply high levels of nitrogen, possibly in the range of pounds of nitrogen per acre. However, it's important to limit such high application rates to soils that have a lower risk of erosion and runoff.

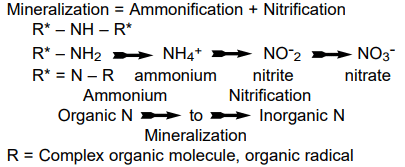

Nitrogen present in organic materials such as plant residues, animal manures, sewage, and soil organic matter exists in the form of proteins, amino acids, and other materials from plants and microorganisms. This nitrogen becomes available to plants only after it undergoes decomposition by soil microorganisms. This process is referred to as "mineralization," with the initial stage known as "ammonification." The ammonium (NH4+) produced during ammonification is then transformed into nitrate-nitrogen (NO3--N) by "nitrifying" bacteria in the soil through a process called "nitrification."

Figure 2: The mineralization process.

The nitrogen cycle, as illustrated in Figure 1, depicts the locations of the ammonification and nitrification processes. Ammonium ions (NH4+), which carry a positive charge and are produced through ammonification or introduced to the soil via fertilizers, are attracted to the negatively charged clay particles in the soil. However, in the majority of non-arid soils, NH4+ ions quickly convert into nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N). Growing plants primarily take up their nitrogen in the form of nitrate (NO3-).

Inorganic nitrogen sources encompass ammonia (NH3), ammonium (NH4+), amine (NH2+), and nitrate (NO3-). Most fertilizer materials either contain or eventually yield NH4+, which swiftly transforms into NO3- once within the soil.