Indian Polity: May 2024 Current Affairs | Current Affairs & General Knowledge - CLAT PDF Download

Regulating Misleading Advertisements in India

Context

In a bid to protect consumers from misleading advertisements, the Supreme Court of India has issued new directives requiring advertisers to submit self-declarations before promoting their products in the media. Additionally, the Union government has rescinded an AYUSH Ministry letter that omitted Rule 170 of the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945, effective immediately.

Key Directives from the Supreme Court

Submission of Self-Declarations:

- Advertisers must submit self-declarations before promoting products in the media.

- Advertisers are required to confirm that their advertisements do not deceive or make false statements about their products to prevent misleading consumers.

Online Portal for Advertisers:

- Advertisers planning to run TV ads must upload declarations on the 'Broadcast Seva' portal, a one-stop facility for permissions, registrations, and licenses for broadcast-related activities from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

- A similar portal for print advertisers is to be established.

Responsibility of Endorsers:

- Social media influencers, celebrities, and public figures endorsing products must act responsibly.

- Endorsers should have adequate knowledge about the products they promote to avoid deceptive advertising.

Ensuring Consumer Protection:

- Establish a transparent process for consumers to report misleading advertisements and ensure they receive updates on complaint status and outcomes.

How Do Misleading Advertisements Violate Ethical Principles?

Violation of Truthfulness:

- Misleading advertisements manipulate consumer perceptions and exploit vulnerabilities for commercial gain.

- They persuade individuals to make purchasing decisions based on false premises.

Fairness and Justice:

- Misleading advertisements create an uneven playing field, giving an unfair advantage to companies that engage in deceptive practices.

- This disadvantages honest competitors and undermines consumer trust.

Consumer Harm:

- Misleading advertisements can lead to financial losses for consumers who purchase products based on false claims, resulting in dissatisfaction.

- They can also harm consumers' physical or mental well-being if the advertised products or services are harmful or ineffective.

Erosion of Trust:

- Repeated exposure to misleading advertisements erodes trust in products, brands, and advertising.

- When consumers feel deceived, they lose confidence in the market's integrity.

How Misleading Advertisements are Regulated in India?

Definition of Misleading Advertisement:

- Defined under Section 2 (28) of the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, as any advertisement that:

- Provides a false description of a product or service.

- Offers false guarantees that mislead consumers.

- Constitutes an unfair trade practice through express representation.

- Deliberately omits essential information about the product.

Central Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA):

- Operates under the Department of Consumer Affairs.

- Established under section 10 of the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, it regulates consumer rights violations and unfair trade practices.

- Empowers the CCPA to prevent false or misleading advertisements and ensure consumer rights are protected.

Enforcement of Guidelines:

- The CCPA enforces the ‘Guidelines for Prevention of Misleading Advertisements and Endorsements for Misleading Advertisements, 2022’.

- Issued per the powers conferred by the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, to protect consumers from unsubstantiated claims and exaggerated promises.

Provisions of the Guidelines:

- Define "bait advertising", "surrogate advertisement", and "free claim advertisements".

- Protect children from exaggerated or unsubstantiated claims in advertisements.

- Advertisements targeting children are prohibited from featuring personalities from sports, music, or cinema for products that require a health warning or cannot be purchased by children.

- Disclaimers in advertisements should not hide material information or attempt to correct misleading claims.

- Outline the duties of manufacturers, service providers, advertisers, and advertising agencies to bring more transparency and clarity to advertisements.

Penalties for Violations:

- CCPA can impose penalties of up to 10 lakh rupees on manufacturers, advertisers, and endorsers for misleading advertisements.

- For subsequent violations, the penalty can be up to 50 lakh rupees.

- The Authority can also prohibit the endorser of a misleading advertisement from making any endorsements for up to 1 year, and for subsequent violations, the prohibition can extend up to 3 years.

Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI):

- Deceptive advertising falls under Section-53 of the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006, making it punishable.

- FSSAI mandates advertisements to be truthful, unambiguous, and scientifically substantiated.

- Uses the Food Safety and Standards (Advertisements & Claims) Regulations, 2018, which specifically deal with food-related products, while CCPA’s regulations cover goods, products, and services.

ASCI (Advertisement Standard Council of India):

- A nonstatutory tribunal established as a self-regulated mechanism to introduce advertising ethics in India.

- Judges advertisements based on its Code of Advertising Practice, also known as the ASCI code, applicable to advertisements seen in India, even if from abroad and directed at Indian consumers.

Consumer Protection Act, 1986:

- Grants consumers the right to be informed about goods and services' quality, quantity, and price.

- Section 2(r) covers false advertisements under the definition of unfair trade practices.

- Provides redressal against misleading advertisements.

Cable Television Network Act of 1995 and the Cable Television Amendment Act of 2006:

- Prohibits transmission of advertisements that do not conform to the prescribed advertisement code.

- Ensures advertisements do not offend morality, decency, or religious sensitivities.

Restrictions on Tobacco Advertisement:

- Prohibits direct and indirect advertisement of tobacco products in all forms of media.

- Enforced under the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act, 2003.

Drug and Magic Remedies Act, 1954 & Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940:

- Regulates drug advertisements.

- Prohibits the use of test reports for advertising drugs.

- Penalties for violations include fines and imprisonment.

Regulation of Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques:

- Prohibits advertisement related to prenatal sex determination under the Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Act, 1994.

- Advertising harmful publications under the Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act, 1956, is punishable.

Criminality of Advertisements under the Indian Penal Code (IPC):

- IPC prohibits obscene, defamatory, or inciteful advertisements.

- Offenses related to inciting violence, terrorism, or crime are illegal and punishable under IPC provisions.

Question on Existence of Article 31C

Context

While deliberating on whether the government can acquire and redistribute private property, a 9-judge Bench of the Supreme Court (SC) decided to address another significant issue: does Article 31C still exist?

What is Article 31C of the Indian Constitution?

Article 31C safeguards laws enacted to:

- Ensure that “material resources of the community” are distributed to serve the common good (Article 39(b)).

- Prevent wealth and means of production from being “concentrated” to the “common detriment” (Article 39(c)).

- Under Article 31C, these directive principles (Articles 39(b) and 39(c)) cannot be contested by invoking the right to equality (Article 14) or the rights under Article 19 (freedom of speech, right to assemble peacefully, etc.).

Introduction of Article 31C

- Article 31C was introduced through the Constitution (25th) Amendment Act, 1971.

- The amendment responded to the “Bank Nationalisation Case”, where the SC halted the Centre from acquiring control of 14 commercial banks through the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Act, 1969, due to inadequate ‘right to compensation’.

- The 25th Amendment aimed to overcome obstacles to implementing the Directive Principles of State Policy, introducing Article 31C as one method to achieve this.

The Journey of Article 31C

- The 25th amendment was contested in the Kesavananda Bharati case (1973), where a 13-judge Bench held by a narrow 7-6 majority that the Constitution has a “basic structure” that cannot be altered by constitutional amendments.

- The court struck down the part of Article 31C that stated no law giving effect to DPSP shall be questioned in court for not giving effect to such policy, allowing courts to review laws enacted under Articles 39(b) and 39(c).

- In 1976, the Constitution (42nd) Amendment Act extended Article 31C's protection to all directive principles (Articles 36-51), prioritizing them over fundamental rights hindering socio-economic reforms.

- In 1980, the Minerva Mills v. UoI case led the SC to strike down this expansion, ruling that Parliament’s amending power was limited and could not grant itself “unlimited” powers.

- This raised a question: Did the court’s ruling invalidate Article 31C entirely by striking down part of the 25th amendment?

The Ongoing Case in SC

- The court is hearing a challenge to Chapter VIII-A of the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Act, 1976 (MHADA), which allows the government to acquire “cessed” properties in Mumbai under Article 39(b).

- In 1991, the Bombay High Court upheld the amendment, citing Article 31C's protection for laws enacted under Article 39(b).

- In 1992, this decision was appealed in the SC, raising the question of whether “material resources of the community” under Article 39(b) included private resources like cessed properties.

What are the Arguments in the SC?

- Initially, the 9-judge Bench seemed to align with the Centre’s view to focus on interpreting Article 39(b).

- The next day, the Bench stated that determining whether Article 31C remains after the Minerva Mills decision is necessary to avoid “constitutional uncertainty”.

- Senior Advocate for the petitioners argued that the original Article 31C was replaced by the expanded version in the 42nd Amendment, and its striking down in Minerva Mills does not automatically revive the older provision.

- The Solicitor General for the Centre argued for applying the doctrine of revival, restoring the post-Kesavananda Bharati position on Article 31C.

- He cited Justice Kurian Joseph’s observations in the case striking down the Constitution (99th) Amendment Act (NJAC), where Joseph held that invalidating the substitution and insertion of a constitutional amendment revives the pre-amended provisions automatically.

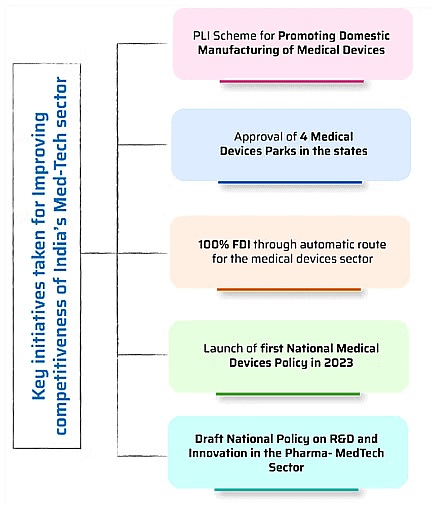

India as a Net Exporter of Medical Consumables

Context

According to the DoP exports surpassed imports in consumables and disposables last year, yet the overall MedTech sector experienced an import surge.

- The import was driven primarily by countries like the US, China, and Germany.

About Medtech sector

- MedTech (or Medical Technology) is a segment of healthcare systems that focuses on designing and manufacturing a wide range of medical products/devices for diagnosis, prevention, treatment.

Its major categories are:

- Disposables and consumables

- Electronics and equipment

- Surgical instruments, Implants

India’s Medtech sector

- Current status:

- India’s MedTech sector is projected to grow 28% annually, reaching a size of US$50 billion by 2030.

- India ranks as the 4th largest market for medical devices in Asia and stands among the top 20 globally.

- Challenges:

- Indian companies mainly produce low-end product such as syringes, needles, catheters, and blood collection tubes.

- Around 65% of the medical device manufacturers in India are domestic players operating in the consumables segment and catering mainly to local consumption.

- Cost competitiveness, quality assurance, and regulation are major hurdles.

- Focus on the quality, fostering partnerships among stakeholders, boosting investment in research and innovation

Draft Explosives Bill 2024

Context

The Government of India plans to replace the Explosives Act of 1884 with the new Explosives Bill 2024. The draft bill has been proposed by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT). The main objectives are to increase fines for regulatory violations and streamline licensing procedures.

Key Provisions of the Proposed Explosives Bill 2024

- Designation of Licensing Authority: The Union government will appoint the authority responsible for granting, suspending, or revoking licenses under the new bill. Currently, the Petroleum and Explosives Safety Organisation (PESO), operating under the DPIIT, serves as the regulatory body.

- Specified Quantity in Licences: Licences will specify the quantity of explosives that a licensee can manufacture, possess, sell, transport, import, or export within a specific period.

- Penalties for Violations: The bill proposes stricter penalties for violations. Manufacturing, importing, or exporting explosives in violation of regulations may lead to imprisonment for up to three years, a fine of Rs 1,00,000, or both. Possession, use, sale, or transportation of explosives in violation may result in imprisonment for up to two years, a fine of Rs 50,000, or both. Currently, the fine stands at Rs 3,000.

- Streamlined Licensing Procedures: The new bill aims to make licensing procedures more efficient, facilitating businesses in obtaining necessary permits while ensuring strict safety standards are maintained.

The Explosives Act of 1884

- Historical Context: Enacted during British colonial rule, the Explosives Act of 1884 aimed to regulate various aspects of explosives.

- Safety Regulations: The Act applies to different types of explosives, such as gunpowder, dynamite, and nitroglycerin. It mandated safety standards and procedures to mitigate risks, including handling, transportation, and storage guidelines to prevent accidents.

- Regulatory Powers: The Act empowers the Central Government to make rules regarding the manufacture, possession, use, sale, transport, import, and export of explosives. These rules govern the issuance of licences, fees, conditions, and exemptions.

- Prohibition of Dangerous Explosives: The Central Government can prohibit the manufacture, possession, or importation of particularly dangerous explosives for public safety.

- Exemption: The Act does not affect the provisions of the Arms Act, 1959. Licences issued under the Explosives Act are considered valid under the Arms Act, which regulates the possession, acquisition, and carrying of ammunition and firearms and aims to curb illegal weapons and violence. The Arms Act of 1959 replaced the Indian Arms Act of 1878.

- Evolution and Amendments: The Explosives Act has undergone several amendments to adapt to technological advancements and emerging challenges, focusing on enhancing safety standards and regulatory mechanisms.

Increased in Public Health Expenditure

Context

Recent data from the National Health Accounts (NHA) reveal that government health expenditure (GHE) as a proportion of GDP surged by an unprecedented 63% from 2014-15 to 2021-22.

Findings of National Health Accounts (NHA) Data

- Increasing Government Investment in Healthcare:

- Government health expenditure (GHE) as a percentage of GDP significantly increased from 1.13% to 1.84% between 2014-15 and 2021-22.

- Per capita government spending on health nearly tripled during the same period.

- The National Health Policy (NHP) aims to provide accessible and affordable quality healthcare to all, with a target of raising public health expenditure to 2.5% of GDP by 2025.

- Focus on Government-Funded Insurance Schemes:

- Investment in government health insurance schemes, such as Ayushman Bharat PMJAY, has seen a substantial rise (4.4-fold increase since 2013-14).

- There has been an increase in the share of social security spending on health, reflecting a shift towards a more comprehensive healthcare system.

- Decreasing Out-of-Pocket Expenditure (OOPE):

- Out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) on healthcare significantly declined from 62.6% to 39.4% between 2014-15 and 2021-22.

- Factors Contributing to Lower OOPE:

- Schemes like Ayushman Bharat PMJAY help individuals access treatment for serious illnesses without financial strain.

- Increased utilization of government facilities, free ambulance services, and other initiatives contribute to reduced OOPE.

- Free medicines and diagnostics at Ayushman Arogya Kendras (AAMs) further lower healthcare costs.

- Focus on Essential Drugs and Price Regulation:

- Jan Aushadhi Kendras provide affordable generic medicines and surgical items, saving citizens an estimated Rs 28,000 crore since 2014.

- Price regulation of essential medicines, such as stents and cancer drugs, has led to additional savings (estimated at Rs 27,000 crore annually).

- Strengthening Social Determinants of Health:

- Increased government spending includes investments in water supply and sanitation through programs like Jal Jeevan Mission and Swachh Bharat Mission.

- Investing in Healthcare Infrastructure:

- Schemes like Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana and Ayushman Bharat Infrastructure Mission are enhancing medical infrastructure, including AIIMS and ICU facilities.

- Increased health grants to local bodies are strengthening the primary healthcare system.

Challenges Associated with Ensuring the Effective Use of Increased Healthcare Funds in India

- Equity in Access to Improved Facilities:

- Rural populations face challenges such as long travel distances and limited access to specialists, leading to delayed diagnoses and poorer health outcomes.

- A 2021 NITI Aayog report highlights a significant gap in the doctor-patient ratio (1:1100), with a skewed distribution favoring urban areas (1:400).

- The National Health Profile 2022 shows a rise in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes and heart disease, which are costly to treat.

- Misuse and Inefficiencies of Funds:

- Bureaucratic inefficiencies, mismanagement, and potential corruption can divert funds from reaching their intended beneficiaries.

- A 2018 Comptroller and Auditor-General of India (CAG) report identified instances of inflated bills and unnecessary procedures in government hospitals.

- Human Resource Constraints:

- Shortages of doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals often result in overworked staff, compromised quality of care, and longer waiting times.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a doctor-nurse ratio of 4:1, while India currently has a ratio closer to 1:1.

- Currently, a doctor in a government hospital attends to about 11,000 patients, exceeding the WHO recommendation of 1:1000.

Way Forward

- Invest in rural healthcare infrastructure by building affordable hospitals and clinics, and implement programs to train and retain healthcare professionals with incentives such as higher salaries, better housing, and career progression opportunities.

- Establish robust monitoring systems and stricter regulations to ensure efficient fund utilization towards actual patient care and prevent leakages.

- Increase the number of medical professionals in under-staffed government hospitals and improve patient-oriented facilities to enhance patient care and reduce wait times for treatment.

- Invest in preventative healthcare through public health campaigns promoting healthy lifestyles and early disease detection to reduce future healthcare costs.

- Increase spending on public education about healthy eating habits and encourage regular checkups to potentially decrease the incidence of costly-to-treat chronic illnesses.

Corporal Punishment

Context

The Tamil Nadu School Education Department has issued Guidelines for the Elimination of Corporal Punishment in Schools (GECP). The Madras High Court recently emphasized the need to treat children with care and respect, condemning the practice of corporal punishment.

- The Madras High Court has highlighted the importance of treating children with care and respect and has strongly criticized the practice of corporal punishment in schools.

About Corporal Punishment

According to the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009, corporal punishment includes physical punishment, mental harassment, and discrimination. While there is no statutory definition specifically targeting children, the RTE Act prohibits 'physical punishment' and 'mental harassment' under Section 17(1) and makes it a punishable offense under Section 17(2).

Classification: Corporal Punishment can be broadly classified into two types:

- Physical Punishment: Defined by the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) as any action causing pain, hurt, injury, or discomfort to a child. Examples include standing on a bench, holding ears through legs, forced ingestion of substances, and detention in various locations.

- Mental Harassment: Non-physical treatment detrimental to a child's academic and psychological well-being. Examples include sarcasm, derogatory remarks, ridicule, and humiliation.

Regulations for Protection against Corporal Punishment

- Constitutional Provisions:

- Article 21A: Mandates compulsory education for children aged 6-14.

- Article 24: Prohibits child labor in hazardous work until age 14.

- Article 39(e): Obligates the state to prevent child abuse due to economic disparity.

- Article 45: Requires the state to provide care for children aged 0-6.

- Article 51A(k): Mandates parents to ensure education for children aged 6-14.

- NCPCR Guidelines:

- The NCPCR provides guidelines for eliminating corporal punishment, promoting positive engagement with children, and establishing Corporal Punishment Monitoring Cells in schools to ensure compliance.

- Drop boxes for anonymous complaints are to be placed in schools to maintain privacy.

- Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act 2009:

- Section 17: Prohibits corporal punishment and prescribes disciplinary action against offenders.

- Sections 8 and 9: Ensure that children from weaker sections and disadvantaged groups are not discriminated against in education.

- Organizations to Curb Corporal Punishment:

- National Commission for Protection of Child Rights and State Commissions for Protection of Child Rights ensure adherence to the RTE Act, 2009.

- Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000:

- Section 23: Prohibits cruelty to children, prescribing punishment for those causing mental or physical pain.

- Section 75: Prescribes punishment for cruelty to children.

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 1989:

- Article 19: Declares any form of disciplinary violence as unacceptable, ensuring protection from physical or mental harm.

- Indian Penal Code:

- Section 305: Pertains to abetment of suicide by a child.

- Section 323: Pertains to voluntarily causing hurt.

- Section 325: Pertains to voluntarily causing grievous hurt.

Concerns of Corporal Punishment

- Violation of Fundamental Rights: Corporal punishment violates the right to live with dignity, part of the Right to Life under Article 21, and the Right to Education under Article 21A.

- International Obligations: It contravenes Article 37(a) of the UNCRC, which prohibits torture, cruelty, or inhuman punishment.

- Physical & Psychological Concerns: Can lead to physical injuries, anxiety, low self-esteem, and other mental health issues.

- Normalization of Violence: May perpetuate and normalize violence in society.

- Discrimination: Can be applied disproportionately based on gender, race, or socioeconomic status.

- Impact on Education: Leads to higher dropout rates and poor learning outcomes due to fear and intimidation.

- Long-term Trauma: Can cause lasting trauma for sensitive children.

- Negative Outcomes: Leads to behavioral problems, irrespective of sex, race, or ethnicity, and worsens behavior with increased frequency of punishment.

Various Negative Outcomes

- Physical punishment does not improve children's behavior but rather exacerbates it, leading to negative outcomes such as behavioral problems, regardless of the child's sex, race, or ethnicity. The negative impact increases with the frequency of physical punishment.

Annual Review of State Laws 2023

Context

PRS Legislative Research has recently released its "Annual Review of State Laws 2023." The report offers a detailed analysis of the performance of State legislatures across India, highlighting several key aspects of their functioning.

Key Highlights of the Report

Budget Passage Without Discussion:

- In 2023, 40% of the Rs 18.5 lakh crore budget presented by 10 States was passed without any discussion.

- Madhya Pradesh led with 85% of its Rs 3.14 lakh crore budget being passed without discussion.

- The budget process involves multiple stages, including presentation, general discussion, committee scrutiny, and voting on ministry expenditures.

- Kerala, Jharkhand, and West Bengal had 78%, 75%, and 74% of their budgets passed without discussion respectively.

- In 10 States, 36% of expenditure demands were passed without discussion, raising concerns about transparency and scrutiny of state finances.

Public Accounts Committee (PAC):

- The PAC held an average of 24 sittings and tabled 16 reports across the states considered in 2023.

- Five states (Bihar, Delhi, Goa, Maharashtra, and Odisha) did not table any PAC reports.

- Maharashtra’s PAC neither convened nor released any report in the year.

- Tamil Nadu led with 95 reports tabled, showing a wide disparity among states in accountability practices.

- Bihar and Uttar Pradesh had significant PAC sittings without tabling any reports.

- The PAC, usually chaired by a senior opposition member, scrutinises state government accounts and Comptroller and Auditor General reports.

Swift Legislative Action:

- 44% of bills were passed either on the same day or the following day of their introduction, consistent with previous years.

- Gujarat, Jharkhand, Mizoram, Puducherry, and Punjab passed all bills on the day of introduction.

- In 13 of 28 State legislatures, bills were passed within five days of introduction.

- Kerala and Meghalaya took more than five days to pass over 90% of their bills, indicating a more deliberative process.

Ordinances:

- Uttar Pradesh issued 20 ordinances, the highest among states, followed by Andhra Pradesh (11) and Maharashtra (9).

- Ordinances covered various subjects, including new universities, public examinations, and ownership regulations.

- Kerala saw a significant drop in ordinances from 2022 to 2023, raising questions about their necessity and effectiveness.

- Governors use their power to issue ordinances when State Legislative Assemblies are not in session.

Overview of Law Making:

- On average, states passed 18 bills each in 2023, excluding Appropriation Bills for the budget.

- Maharashtra topped with 49 bills, while Delhi and Puducherry passed only two each.

- 59% of bills received the Governor's assent within a month of being passed, but delays were noted in states like Assam, Nagaland, and West Bengal.

- Only 23 out of over 500 bills were referred to legislative committees for deeper examination before being passed.

How can Legislation be Improved for Better Governance and Accountability?

Strengthening PAC:

- Standardize PAC operations with guidelines on sitting frequency, reporting requirements, and timelines.

- Implement mechanisms to monitor and evaluate PAC performance regularly.

- Ensure substantive discussions and report tabling in all PAC sittings to enhance accountability.

Expedited Decision-Making:

- Establish a legislative framework setting a time limit for the Governor's assent to bills.

- Mandate Governors to provide clear reasons for any delay in granting assent to ensure transparency.

Legislative Review:

- Advocate for thorough discussions and debates on budgets before passage in legislatures.

- Strengthen the role of State Finance Commissions and ensure their recommendations are considered in legislative budget discussions.

Legislative Functioning:

- Subject parliamentarians to public scrutiny through a parliamentary ombudsman.

- State Legislatures with fewer than 70 members should meet for at least 50 days annually, and those with more than 70 members should meet for at least 90 days.

- The Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha should hold sessions for a minimum of 100 and 120 days, respectively.

The report highlights the need for improved transparency and accountability in State legislatures to ensure effective governance. Addressing issues in budgetary processes, accountability mechanisms, legislative efficiency, and the use of ordinances is essential for upholding democratic principles and promoting efficient governance at the state level.

Diplomatic Passport

Context

Recently, embroiled in a sex abuse case, one of the Indian political Party’s Member of Parliament (MP) fled to Germany on a diplomatic passport.

- It has a maroon cover and is valid for five years or less.

- Holders of such passports are entitled to certain privileges and immunities as per the international law, including immunity from arrest, detention, and certain legal proceedings in the host country.

Issuing Authority

The Ministry of External Affair’s (MEA) Consular, Passport & Visa Division issues diplomatic passports (‘Type D’ passports) to people falling in broadly five categories:

- those with diplomatic status;

- government-appointed individuals travelling abroad for official business;

- officers working under the branches A and B of the Indian Foreign Service (IFS), normally at the rank of Joint Secretary and above; and

- Relatives and immediate family of officers employed in IFS and MEA.

- oselect individuals who are authorized to undertake official travel on behalf of the government”

- The MEA issues visa notes to government officials going abroad for an official assignment or visit.

Revocation of Passport

- As per the Passport Act 1967, the passport authority may, as per the provisions of sub-section (1) of section 6 or any notification under section 19, cancel a passport or travel document, with the previous approval of the Central government.

- The passport authority can impound or revoke a passport if the authority believes that the passport holder or travel document is in wrongful possession; if the passport was obtained by the suppression of material information or on the basis of wrong information provided by the individual; if it is brought to the notice of the passport authority that the individual has been issued a court order prohibiting his departure from India or has been summoned by court.

- A diplomatic passport can be revoked upon orders from a court during proceedings with respect to an offence allegedly carried out by the passport holder before a criminal court.

What is an Operational Visa Exemption Agreement?

- India has operational visa exemption agreements for holders of diplomatic passports with 34 countries and Germany is one amongst them.

- According to a reciprocal deal signed in 2011, holders of Indian diplomatic passports do not require a visa to visit Germany, provided their stay does not exceed 90 days.

- India has similar agreements with countries such as France, Austria, Afghanistan, Czech Republic, Italy, Greece, Iran, and Switzerland.

- India also has agreements with 99 other countries wherein apart from diplomatic passport holders, even those holding service and official passports can avail operational visa exemption for stays upto 90 days.

SC Rejects Centre’s Plea for Administrative Spectrum Allocation

Context

The Supreme Court of India has made a significant decision by rejecting the Centre’s plea to permit administrative allocation of spectrum. This decision reaffirms the principle of open and transparent auction for allocating this scarce natural resource.

Reasons for Supreme Court’s Rejection of Centre’s Application

Misconceived Application

- The Registrar considered the application for clarification as misguided. Citing Order XV Rule 5 of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, the Registrar noted the application lacked reasonable cause and contained frivolous content, justifying its refusal.

Precedent from 2G Spectrum Case

- The Supreme Court reaffirmed that spectrum allocation to private entities must follow open and transparent auction procedures. This principle was established in the landmark judgment of the 2G spectrum case, commonly referred to as the "2G spectrum scam" case, which occurred 12 years ago.

Importance of Fairness and Transparency

- Spectrum allocation is a crucial process. Allowing administrative allocation would grant the government sole authority to choose operators for distributing airwaves, contradicting the principles of fairness and transparency, as highlighted by the Supreme Court.

What is Airwaves/Spectrum?

- Airwaves, also known as spectrum, refer to the radio frequencies within the electromagnetic spectrum used for wireless communication services.

- The government manages and allocates airwaves to companies or sectors for their use.

- Spectrum is auctioned by the government to telecom operators to provide communication services to consumers.

2G Spectrum Scam Verdict

- In 2008, the government sold 122 2G licenses on a first-come-first-serve (FCFS) basis to specific telecom operators.

- Allegations surfaced about a ₹30,984 crore loss to the exchequer due to discrepancies in the allocation process.

- Petitions were filed in the Supreme Court alleging a ₹70,000 crore scam in the grant of telecom licenses in 2008.

- In February 2012, the Supreme Court canceled the licenses, advocating for competitive auctions as the sole method to allocate spectrum.

Centre’s Plea: Arguments in Favor of Allocating Spectrum Through Administrative Processes

Assignment for Various Purposes

- Spectrum assignment is needed not only for commercial telecom services but also for sovereign and public interest functions such as security, safety, and disaster preparedness.

- Certain spectrum categories have unique uses where auctions may not be ideal, such as for captive, backhaul, or sporadic use.

Situation of Lower Demand Than Supply

- Administrative allocation is necessary when demand is lower than supply or for space communication, where sharing spectrum among multiple players is more efficient.

- Since the 2012 decision, non-commercial spectrum allocation has been temporary. The government seeks to establish a solid framework for assigning spectrum, including methods other than auctions.

2012 Presidential Reference

- Referring to remarks by a previous Constitution Bench on a Presidential reference regarding the 2012 verdict, the government emphasized that the auction method is not a constitutional mandate for the alienation of natural resources, excluding spectrum.

- However, spectrum, as per the law declared in the 2G case, is to be alienated solely by auction and no other method.

The Telecommunications Act, 2023

Empowers Government to Use Administrative Route

- The Telecommunications Act, 2023, passed by Parliament, grants the government the authority to assign spectrum for telecommunication through administrative processes other than auctions.

- This provision applies to entities listed in the First Schedule, including those engaged in national security, defense, and law enforcement, as well as Global Mobile Personal Communication by Satellites (GMPCS) providers like Space X and Bharti Airtel-backed OneWeb.

Assignment of Part of Assigned Spectrum

- The government has the discretion to assign part of a spectrum already allocated to one or more additional entities, referred to as secondary assignees.

- The Act also empowers the government to terminate assignments where a spectrum or a part of it has remained underutilized for insufficient reasons.

Challenges Faced by Street Vendors

A decade has elapsed since the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act was implemented on May 1, 2014.

About Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014

- Enacted to legalize the vending rights of street vendors (SVs).

- Aimed at safeguarding and regulating street vending in urban areas, with rules and schemes at the State level, and enforcement by Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) through by-laws, planning, and regulation.

- The Act clearly defines the roles and responsibilities of vendors and various levels of government.

- Commits to accommodating all 'existing' vendors in designated vending zones and issuing vending certificates (VCs).

- Establishes a participatory governance structure via Town Vending Committees (TVCs).

- Requires that street vendor representatives make up 40% of TVC members, including a sub-representation of 33% women SVs.

- These committees are responsible for ensuring all existing vendors are included in vending zones.

- Outlines mechanisms for grievance and dispute resolution, proposing the formation of a Grievance Redressal Committee chaired by a civil judge or judicial magistrate.

- Mandates that States/ULBs conduct a survey to identify SVs at least once every five years.

|

98 videos|939 docs|33 tests

|