CAT Exam > CAT Questions > A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactl...

Start Learning for Free

A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?

- a)12 min

- b)1 hr 24 min

- c)2 hr 12 min

- d)None of these

Correct answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?

| FREE This question is part of | Download PDF Attempt this Test |

Most Upvoted Answer

A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and ...

To solve this problem, we need to analyze the movements of the hour and minute hands of the clock in both observations.

First Observation:

- The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark, indicating that the time is at a whole hour.

- The minute hand is six minutes ahead of the hour hand.

- Let's assume that the time is h:00, where h represents the whole hour.

- At h:00, the hour hand is exactly at the minute mark, while the minute hand is at the 6-minute mark.

- The minute hand moves 360 degrees in 60 minutes, which means it moves 6 degrees per minute.

- The hour hand moves 30 degrees in 60 minutes, which means it moves 0.5 degrees per minute.

- If the minute hand is 6 minutes ahead of the hour hand, it means it has covered an additional 6 * 6 = 36 degrees.

- Therefore, the minute hand is at the 6 + 36 = 42-minute mark.

- The hour hand is still at the minute mark, indicating that the time is still h:00.

Second Observation:

- The hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark, indicating that the time has changed to a different whole hour.

- The minute hand is seven minutes ahead of the hour hand.

- Let's assume that the time is k:00, where k represents the new whole hour.

- At k:00, the hour hand is on a different minute mark, while the minute hand is at the 7-minute mark.

- Similar to the first observation, the minute hand moves 6 degrees per minute, and the hour hand moves 0.5 degrees per minute.

- If the minute hand is 7 minutes ahead of the hour hand, it means it has covered an additional 7 * 6 = 42 degrees.

- Therefore, the minute hand is at the 7 + 42 = 49-minute mark.

- The hour hand is now on a different minute mark, indicating that the time is k:00.

Time Elapsed between the Observations:

- The difference in the minute marks between the two observations is 49 - 42 = 7 minutes.

- However, the hour hand has also moved from h:00 to k:00, which indicates a time difference of k - h = 1 hour.

- Therefore, the total time elapsed between the first and second observations is 1 hour + 7 minutes = 1 hour 7 minutes.

- Since 1 hour is equal to 60 minutes, the total time elapsed is 60 + 7 = 67 minutes.

- Converting this to hours and minutes, we get 1 hour 7 minutes = 1 hr 7 min.

Therefore, the correct answer is option (c) 2 hr 12 min.

First Observation:

- The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark, indicating that the time is at a whole hour.

- The minute hand is six minutes ahead of the hour hand.

- Let's assume that the time is h:00, where h represents the whole hour.

- At h:00, the hour hand is exactly at the minute mark, while the minute hand is at the 6-minute mark.

- The minute hand moves 360 degrees in 60 minutes, which means it moves 6 degrees per minute.

- The hour hand moves 30 degrees in 60 minutes, which means it moves 0.5 degrees per minute.

- If the minute hand is 6 minutes ahead of the hour hand, it means it has covered an additional 6 * 6 = 36 degrees.

- Therefore, the minute hand is at the 6 + 36 = 42-minute mark.

- The hour hand is still at the minute mark, indicating that the time is still h:00.

Second Observation:

- The hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark, indicating that the time has changed to a different whole hour.

- The minute hand is seven minutes ahead of the hour hand.

- Let's assume that the time is k:00, where k represents the new whole hour.

- At k:00, the hour hand is on a different minute mark, while the minute hand is at the 7-minute mark.

- Similar to the first observation, the minute hand moves 6 degrees per minute, and the hour hand moves 0.5 degrees per minute.

- If the minute hand is 7 minutes ahead of the hour hand, it means it has covered an additional 7 * 6 = 42 degrees.

- Therefore, the minute hand is at the 7 + 42 = 49-minute mark.

- The hour hand is now on a different minute mark, indicating that the time is k:00.

Time Elapsed between the Observations:

- The difference in the minute marks between the two observations is 49 - 42 = 7 minutes.

- However, the hour hand has also moved from h:00 to k:00, which indicates a time difference of k - h = 1 hour.

- Therefore, the total time elapsed between the first and second observations is 1 hour + 7 minutes = 1 hour 7 minutes.

- Since 1 hour is equal to 60 minutes, the total time elapsed is 60 + 7 = 67 minutes.

- Converting this to hours and minutes, we get 1 hour 7 minutes = 1 hr 7 min.

Therefore, the correct answer is option (c) 2 hr 12 min.

Free Test

FREE

| Start Free Test |

Community Answer

A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and ...

The hour hand is exactly on a minute mark five times per hour - on the hour, twelve minutes past the hour, twenty four minutes past, thirty six minutes past and forty eight minutes past. There are 60 divisions on a clock. Let the first division be 1, which is just next to 12.

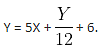

Let X be the number of hours and Y be the number of minutes past the hour. When the hour hand is on a minute mark, the position of the hour hand is on the  division and the position of the minute hand is on Y.

division and the position of the minute hand is on Y.

division and the position of the minute hand is on Y.

division and the position of the minute hand is on Y.On the first occasion,  This is equivalent to 60X = 11Y - 72.

This is equivalent to 60X = 11Y - 72.

This is equivalent to 60X = 11Y - 72.

This is equivalent to 60X = 11Y - 72.Since Y can only take one of the values in the set {0, 12, 24, 36, 48}, it can be determined that the only legal values for the equation are X = 1 and Y = 12.

So, the time is 1:12.

Similarly, the second occasion's equation is 60X = 11Y - 84.

The only legal values here are X = 3 and Y = 24.

So, the time is 3:24.

Between 1:12 and 3:24, two hours and twelve minutes have elapsed.

Attention CAT Students!

To make sure you are not studying endlessly, EduRev has designed CAT study material, with Structured Courses, Videos, & Test Series. Plus get personalized analysis, doubt solving and improvement plans to achieve a great score in CAT.

|

Explore Courses for CAT exam

|

|

Similar CAT Doubts

A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? for CAT 2024 is part of CAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the CAT exam syllabus. Information about A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for CAT 2024 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?.

A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? for CAT 2024 is part of CAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the CAT exam syllabus. Information about A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for CAT 2024 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for CAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for CAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an

ample number of questions to practice A clock is observed. The hour hand is exactly at the minute mark and the minute hand is six minutes ahead of it. Later, the clock is observed again. This time, the hour hand is exactly on a different minute mark and the minute hand is seven minutes ahead of it. How much time elapsed between the first and the second observations?a)12 minb)1 hr 24 minc)2 hr 12 mind)None of theseCorrect answer is option 'C'. Can you explain this answer? tests, examples and also practice CAT tests.

|

Explore Courses for CAT exam

|

|

Suggested Free Tests

Signup for Free!

Signup to see your scores go up within 7 days! Learn & Practice with 1000+ FREE Notes, Videos & Tests.